JJ Hemadehismark Complete.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE GARDENS REACH of the BRISBANE RIVER Kangaroo Point — Past and Present [By NORMAN S

600 THE GARDENS REACH OF THE BRISBANE RIVER Kangaroo Point — Past and Present [By NORMAN S. PIXLEY, M.B.E., V.R.D., Kt. O.N., F.R.Hist.S.Q.] (Read at the Society's meeting on 24 June 1965.) INTRODUCTION [This paper, entitied the "Gardens Reach of the Brisbane River," describes the growth of shipping from the inception of Brisbane's first port terminal at South Brisbane, which spread and developed in the Gardens Reach. In dealing briefly wkh a period from 1842 to 1927, it men tions some of the vessels which came here and a number of people who travelled in them. In this year of 1965, we take for granted communications in terms of the Telestar which televises in London an inter view as it takes place in New York. News from the world comes to us several times a day from newspapers, television and radio. A letter posted to London brings a reply in less than a week: we can cable or telephone to London or New York. Now let us return to the many years from 1842 onward before the days of the submarine cable and subsequent inven tion of wireless telegraphy by Signor Marconi, when Bris bane's sole means of communication with the outside world was by way of the sea. Ships under sail carried the mails on the long journeys, often prolonged by bad weather; at best, it was many months before replies to letters or despatches could be expected, or news of the safe arrival of travellers receivd. Ships vanished without trace; news of others which were lost came from survivors. -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

The History of the Coronation Drive Office Park

The History of the Coronation Drive Office Park Angus Veitch April 2014 Version 1.0 (6 April 2014) This report may be cited as: Angus Veitch (2014). History of the Coronation Drive Office Park. Brisbane, QLD. More information about the history of Milton and its surrounds can be found at the author’s website, www.oncewasacreek.org. Acknowledgements This report was prepared for AMP Capital through a project managed by UniQuest Ltd (UniQuest Project No: C01592). Thank you to Ken Neufeld, Leon Carroll and others at AMP Capital for commissioning and supporting this investigation. Thanks also to Marci Webster-Mannison (Centre for Sustainable Design, University of Queensland) and to UniQuest for overseeing the work and managing the contractual matters. Thank you also to Annabel Lloyd and Robert Noffke at the Brisbane City Archives for their assistance in identifying photographs, plans and other records pertaining to the site. Disclaimer This report and the data on which it is based are prepared solely for the use of the person or corporation to whom it is addressed. It may not be used or relied upon by any other person or entity. No warranty is given to any other person as to the accuracy of any of the information, data or opinions expressed herein. The author expressly disclaims all liability and responsibility whatsoever to the maximum extent possible by law in relation to any unauthorised use of this report. The work and opinions expressed in this report are those of the Author. History of the Coronation Drive Office Park Summary This report examines the history of the site of the Coronation Drive Office Park (the CDOP site), which is located in Milton, Brisbane, bounded by Coronation Drive, Cribb Street, the south-western railway line and Boomerang Street. -

Queensland Review

Queensland Review http://journals.cambridge.org/QRE Additional services for Queensland Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here A House of Sticks: A History of Queenslander Houses in Maryborough Donald Watson Queensland Review / Volume 19 / Special Issue 01 / June 2012, pp 50 - 74 DOI: 10.1017/qre.2012.6, Published online: 03 September 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1321816612000062 How to cite this article: Donald Watson (2012). A House of Sticks: A History of Queenslander Houses in Maryborough. Queensland Review, 19, pp 50-74 doi:10.1017/qre.2012.6 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/QRE, IP address: 130.102.82.103 on 27 Nov 2015 A House of Sticks: A History of Queenslander Houses in Maryborough Donald Watson Some years ago, when South-East Queensland was threatened with being overrun with Tuscan villas, the Brisbane architect John Simpson proposed that revenge should be taken on Italy by exporting timber and tin shacks in large numbers to Tuscany. The Queenslanders would be going home – albeit as colonial cousins – taking with them their experience of the sub-tropics. Without their verandahs but with their pediments intact, the form and planning, fenestration and detailing can be interpreted as Palladian, translated into timber, the material originally available in abundance for building construction. ‘High-set’, the local term for South-East Queensland’s raised houses, denotes a feature that is very much the traditional Italian piano nobile [‘noble floor’]: the principal living areas on a first floor with a rusticated fac¸ade of battens infilling between stumps and shaped on the principal elevation as a superfluous arcade to a non-existent basement storey. -

Old Government House Brisbane

OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE BRISBANE OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE A preliminary assessment of conservation and adaptation works for QUT © COPYRIGHT Allom Lovell Pty Ltd, July 2002 \\NTServer\public\Projects\96020 QUT ongoing\Reports\OGH 2002\r01.doc OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE CONTENTS i 1 INTRODUCTION 1 THE QUT BRIEF 1 PREVIOUS REPORTS & DOCUMENTS & APPROVALS 2 ROOM NAMES 2 COST ESTIMATES 2 1.2 A LONGER TERM VIEW 3 OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE PROJECT AND THE QUEENSLAND HERITAGE COUNCIL 3 1.3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 THE BUILDING CODE OF AUSTRALIA 4 NEW USES 4 STAGED WORKS 4 COSTINGS 5 2 HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE 6 2.1 THE COLONY OF QUEENSLAND 6 2.2 GOVERNMENT HOUSE 7 PLANNING AND ROLES 7 EXTENSIONS 8 2.3 OTHER USES 10 2.4 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 11 3 CONDITION ASSESMENT 14 3.1 INTERIOR 14 CELLAR 14 GROUND FLOOR 14 FIRST FLOOR 15 3.2 EXTERIOR 15 OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE CONTENTS ii 3.3 BUILDING CODE OF AUSTRALIA AUDIT 21 4 RECOMMENDED WORKS 23 4.1 URGENT WORKS 23 4.2 IMMEDIATE WORKS 24 4.3 EXTERIOR WORKS 25 4.4 INTERIOR WORKS 26 STAGE 1: BILLIARD ROOM AND SECRETARY’S AND ADC OFFICE 28 STAGE 2: REAR SERVANT’S AND GOVERNOR’S STAFF AREAS 29 STAGE 3:UPSTAIRS FRONT PRIVATE ROOMS 29 STAGE 4:REAR KITCHEN WING 30 STAGE 5: DOWNSTAIRS FRONT RECEPTION ROOMS 30 TYPICAL SCOPE OF WORK 30 SERVICES 31 ACCESS 32 4.5 COSTINGS 32 5 THE LANDSCAPE 33 6 APPENDIX 36 6.1 ROOM NAMES 36 6.2 BUILDING CODE OF AUSTRALIA 38 INTRODUCTION 39 METHODOLOGY 39 RESEARCH 39 OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE CONTENTS iii BUILDING ACT AND REGULATIONS 39 CERTIFICATE OF CLASSIFICATION 39 DESCRIPTION OF THE BUILDING 39 PART A – GENERAL PROVISIONS 41 PART B – STRUCTURE 41 PART C – FIRE RESISTANCE 41 PART D – ACCESS AND EGRESS 43 PART E – SERVICES AND EQUIPMENT 46 PART F – HEALTH AND AMENITY 48 RECOMMENDATIONS 49 6.3 COST ESTIMATES 52 OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1 INTRODUCTION ld Government House is one of the earliest buildings in Queensland Oand is significant as the only purpose built governor’s residence in the state and as part of the establishment of tertiary institutions in the state. -

SQUATTERS, SELECTORS and — DARE I SAY IT — SPECULATORS by Helen Gregory Read to the Royal Historical Society of Queensland on 23 June, 1983

SQUATTERS, SELECTORS AND — DARE I SAY IT — SPECULATORS by Helen Gregory Read to the Royal Historical Society of Queensland on 23 June, 1983. This paper attempts to fill a small part of one of the many large gaps which currently exist in the pubhshed history of Brisbane. Books and articles published over the past twenty-five years have added to our knowledge and understanding of the exploration of the Brisbane region, its beginnings in convictism, its built environment, its adminis trative history and the broad lines of development of the city and its suburbs. This paper looks at a rather different aspect; it looks at people as well as events and at land rather than buildings. It concentrates on two very important decades, the 1840's and 1850's, which are so far either largely absent from the published record or mentioned briefly between the fascinations of convictism and the' excitement of newly independent colonial and city government. These two decades were, however, very important formative years in the city's history during which the main outlines of the future development of the Brisbane area became discernible; the battle for urban dominance between Brisbane and Ipswich was played out and a major political division which has been a persistent motif in Queens land politics arose between an essentially conservative rural interest and a more liberal urban interest. The quest for land and the development of the land have been equally persistent motifs. This paper looks at some of the land bought and sold at this time, at two of the people who invested in it, and at the relationship between their land holdings and their business and political activities. -

The Naming of St Lucia and Ironside

The Naming of St Lucia and Ironside Peter Brown St Lucia History Group Paper No 5 ST LUCIA HISTORY GROUP CONTENTS: Page 1. Introduction 1 2. The Naming of St Lucia 4 3. The Naming of Ironside 7 4. The Wilson Family 8 5. The Official Suburb of St Lucia 15 Peter Brown 2017 Private Study paper – not for general publication St Lucia History Group PO Box 4343 St Lucia South QLD 4067 Email: [email protected] Web: brisbanehistorywest.wordpress.com PGB/History/Papers/5Naming Page 1 of 17 Printed July 28, 2017 ST LUCIA HISTORY GROUP ST LUCIA HISTORY GROUP RESEARCH PAPER 5. ST LUCIA - NAMING OF ST LUCIA AND IRONSIDE 1. INTRODUCTION The names ‘St Lucia, Ironside, and Long Pocket’ did not come into use until the mid 1880s, but for ease of understanding are used herein as the descriptors for the areas now using those names. When the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement moved from Redcliffe in 1825 the new settlement was known at first as Eden Glassie, (an amalgam of Glasgow and Edinburgh). However by 1826 Captain Logan refers to the settlement as Brisbane Town.1. Upon the closure of the Penal Settlement in 1842 the adjacent area became the ‘Moreton Bay Pastoral District’, with Dr Simpson appointed as the first Crown Lands Commissioner on 5 May 1842.2 The only town within the Moreton District was the remains of the original convict settlement which retained the colloquial name of Brisbane, although its formal moniker was ‘Town of Brisbane’ As closer settlement occurred it was necessary to progressively subdivide the Moreton Bay Pastoral Division into Counties and Parishes, and in 1842 under Governor Sir George Gipps the County of Stanley was formally established. -

'Young Queensland Will Then Become the Queen of Lands'

‘Young Queensland The Old Government House site before Queensland was established will then become the For thousands of years the river and surrounding land has been the traditional country of the Turrbal Queen of Lands’ and Jagera people. Moreton Bay Courier, 13 December 1859 In 1825 the Moreton Bay penal settlement was established on the northern bank of the river. After fourteen years the convict settlement closed Separation achieved and in 1842 Brisbane was officially opened to all ‘A great event in our history’ settlers. Throughout the 1850s, the Moreton Bay District of New South Wales had fought an often bitter campaign to become a separate, northern colony. QUEEN’S INSTRUCTIONS In early July 1859, ‘the glorious news’ arrived in On 6 June 1859 Queen Brisbane that separation had finally been won. The Victoria signed Letters new colony was to be called Queen’s Land – a name Patent, the document that Queen Victoria had coined herself – and Sir George created Queensland, and Bowen was appointed the colony’s first governor sent Sir George Bowen instructions (below). Months later on 10 December 1859 Governor Bowen Image courtesy of The Royal finally arrived in Brisbane and Queensland was Collection © 2008 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. officially proclaimed a separate self-governing colony. Document image courtesy of Queensland was the only Australian colony to start Government House, Brisbane. with its own parliament without first being a British controlled Crown Colony. An estimated 4000 jubilant people lined Brisbane’s streets to welcome Sir George and Lady Bowen as they made their way from the Botanic Gardens landing to the temporary Government House. -

Download Citation

Heritage Citation Losch's Timber Duplex Key details Addresses At 61 Gloucester Street, Spring Hill, Queensland 4000 Type of place Duplex Period Victorian 1860-1890 Style Queenslander Lot plan L21_RP9857 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 14 September 2018 Date of Citation — November 2014 Construction Roof: Corrugated iron; Walls: Timber Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (B) Rarity This two-storey residence was constructed as a rental property for owner George Losch, a cab driver and property investor and was originally a duplex. It was probably built in 1884 to replace an older rental property which had burned down. The house exemplifies the trend in the 1880s towards investment properties to capitalise on escalating demand for residential accommodation in Spring Hill. It is also an unusual example of a purpose-built multi-tenanted dwelling, which were rare in Brisbane but joined other examples in Gloucester Street. History Spring Hill is one of the earliest settled areas of Brisbane, having been occupied since the 1820s. A windmill was erected on the height of Wickham Terrace in 1829 to process grain for the Moreton Bay penal colony. When the Date of Citation — November 2014 Page 1 area was opened for free settlement in 1842 the Crown offered parcels of land within the town of Brisbane for sale. Land in Spring Hill followed, with surveys, subdivisions and sales occurring in the 1850s. The area was in walking distance of the city and Fortitude Valley, increasing its residential appeal. The topography of Spring Hill quickly separated the wealthy from working class, with grand houses built on the ridges for the more well-to-do and cottages on small allotments for the working class down the slopes towards Hanly’s Valley and Spring Hollow. -

The French Disconnection

THE FRENCH DISCONNECTION MILES LEWIS French influence in Australian architecture and building was very conside rable up to the time of the Great War, but it was nearly always indirect. First it arrived by way of Britain, and then by way of Germany and the United States as well. The only major direct link was the importation, mainly from 1890- 1914, of the Marseilles pattern roof tile. It was this direct assimilation of a component not widely known in France, and hardly known at all in Britain, that finally produced an enduring and totally naturalised French element of Austra lian building which remains with us today. PISE DE TERRE The earlier arm's length influence is most strongly shown in the case of pise de terre construction, for this was used hardly at all in England, and yet its quite extensive use in Australia was based upon English versions of ultimately French material. As this strange course of events has been discussed by the present writer elsewhere,1 it can be summarised here with only minor additions. Pise construction had apparently been introduced to France by Hannibal and had become totally acclimatised, especially in the Lyonnais, before it was quite suddenly rediscovered and promulgated in 1772-1797 by Georges-Claude Goif- fon, the Abbe Francois Pilatre de Rozier, Boulard (a building inspector at Lyons), Francois Cointeraux, and Jancour (a refugee priest).2 These accounts attracted the attention of the English architect Henry Holland, who built some experimental structures in pise at Woburn Abbey in 1787-8, and of the Board of Agriculture.3 There are only sporadic references to other experiments in England approa ching the character of pise, which is distinguished by the fact that it is formed of fairly dry gravelly soil rammed into place in thin layers between timber form- work, which is repositioned until a wall is complete. -

Hansard 6 Sep 2000

6 Sep 2000 Legislative Assembly 2953 WEDNESDAY, 6 SEPTEMBER 2000 Lytton National Park, Quarantine Station From Mr Lucas (135 petitioners) requesting the House to take the necessary steps to have the Quarantine Station building Mr SPEAKER (Hon. R. K. Hollis, Redcliffe) moved back to the Lytton National Park and read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. that adequate funding be provided to make it available for heritage displays and performances for students, tourists and CRIMINAL JUSTICE COMMISSION general public. Report Mr SPEAKER: I have to report that today Cairns-Atherton Tableland, Highway Link I received from the Chairperson of the Criminal From Mr Nelson (3,600 petitioners) Justice Commission a report titled "Allegations requesting the House to construct a highway of electoral fraud—Report on an advice by link between Cairns and the Atherton P. D. McMurdo, QC", and I table the said Tableland on the alignment identified as Route report. S7 by the Integrated Transport Study for the Hon. T. M. MACKENROTH (Chatsworth— Kuranda Range and known locally as the Lake ALP) (Leader of the House) (9.32 a.m.): I Morris/Davies Creek Road. move— "That the report be printed." Police Resources, Coolangatta Ordered to be printed. From Mr Quinn (1,060 petitioners) requesting the House to ensure that more police and resources are assigned to crime AUDITOR-GENERAL'S REPORT fighting in the Coolangatta area. Petitions received. Mr SPEAKER: I have to report that today I received from the Auditor-General a report titled "Audit report No. 6 1999-2000—Results MINISTERIAL STATEMENT of audits performed for 1998-99 as at 30 June Government Achievements 2000", and I table the said report. -

Timeline for Brisbane River Timeline Is a Summary of Literature Reviewed and Is Not Intended to Be Comprehensive

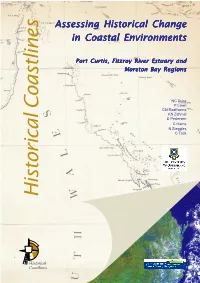

Assessing Historical Change in Coastal Environments Port Curtis, Fitzroy River Estuary and Moreton Bay Regions NC Duke P Lawn CM Roelfsema KN Zahmel D Pedersen C Harris N Steggles C Tack Historical Coastlines HISTORICAL COASTLINES Assessing Historical Change in Coastal Environments Port Curtis, Fitzroy River Estuary and Moreton Bay Regions Norman C. Duke, Pippi T. Lawn, Chris M. Roelfsema, Katherine N. Zahmel, Dan K. Pedersen, Claire Harris, Nicki Steggles, and Charlene Tack Marine Botany Group Centre for Marine Studies The University of Queensland Report to the CRC for Coastal Zone Estuary and Waterway Management July 2003 HISTORICAL COASTLINES Submitted: July 2003 Contact details: Dr Norman C Duke Marine Botany Group, Centre for Marine Studies The University of Queensland, Brisbane QLD 4072 Telephone: (07) 3365 2729 Fax: (07) 3365 7321 Email: [email protected] Citation Reference: Duke, N. C., Lawn, P. T., Roelfsema, C. M., Zahmel, K. N., Pedersen, D. K., Harris, C. Steggles, N. and Tack, C. (2003). Assessing Historical Change in Coastal Environments. Port Curtis, Fitzroy River Estuary and Moreton Bay Regions. Report to the CRC for Coastal Zone Estuary and Waterway Management. July 2003. Marine Botany Group, Centre for Marine Studies, University of Queensland, Brisbane. COVER PAGE FIGURE: One of the challenges inherent in historical assessments of landscape change involves linking remote sensing technologies from different eras. Past and recent state-of-the-art spatial images are represented by the Queensland portion of the first map of Australia by Matthew Flinders (1803) overlaying a modern Landsat TM image (2000). Design: Diana Kleine and Norm Duke, Marine Botany Group.