The Making and Meaning of Gay Space : the Case of the Castro In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Queer Aes- Thetic Is Suggested in the Nostalgia of Orton’S List of 1930S Singers, Many of Whom Were Sex- Ual Nonconformists

Orton in Deckchair in Tangier. Courtesy: Orton Collection at the University of Leicester, MS237/5/44 © Orton Estate Rebel playwright Joe Orton was part of a ‘cool customer’, Orton shopped for the landscape of the Swinging Sixties. clothes on Carnaby Street, wore ‘hipster Irreverent black comedies that satirised pants’ and looked – in his own words the Establishment, such as Entertaining – ‘way out’. Although he cast himself Mr Sloane (1964), Loot (1965) and as an iconoclast, Emma Parker suggests What the Butler Saw (first performed that Orton’s record collection reveals a in 1969), contributed to a new different side to the ruffian playwright counterculture. Orton’s representation who furiously pitched himself against of same-sex desire on stage, and polite society. The music that Orton candid account of queer life before listened to in private suggests the same decriminalisation in his posthumously queer ear, or homosexual sensibility, that published diaries, also made him a shaped his plays. Yet, stylistically, this gay icon. Part of the zeitgeist, he was music contradicts his cool public persona photographed with Twiggy, smoked and reputation for riotous dissent. marijuana with Paul McCartney and wrote a screenplay for The Beatles. Described by biographer John Lahr as A Q U E E R EAR Joe Orton and Music 44 Music was important to Joe Orton from an early age. His unpublished teenage diary, kept Issue 37 — Spring 2017 sporadically between 1949 and 1951, shows that he saved desperately for records in the face of poverty. He also lovingly designed and constructed a record cabinet out of wood from his gran’s old dresser. -

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk Riya Kalra Junior Division Individual Exhibit Student-composed words: 499 Process paper: 500 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: Black, Jason E., and Charles E. Morris, compilers. An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk's Speeches and Writings. University of California Press, 2013. This book is a compilation of Harvey Milk's speeches and interviews throughout his time in California. These interviews describe his views on the community and provide an idea as to what type of person he was. This book helped me because it gave me direct quotes from him and allowed me to clearly understand exactly what his perspective was on major issues. Board of Supervisors in January 8, 1978. City and County of San Francisco, sfbos.org/inauguration. Accessed 2 Jan. 2019. This image is of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from the time Harvey Milk was a supervisor. This image shows the people who were on the board with him. This helped my project because it gave a visual of many of the key people in the story of Harvey Milk. Braley, Colin E. Sharice Davids at a Victory Party. NBC, 6 Nov. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/sharice-davids-lesbian-native-american-makes- political-history-kansas-n933211. Accessed 2 May 2019. This is an image of Sharcie Davids at a victory party after she was elected to congress in Kansas. This image helped me because ti provided a face to go with he quote that I used on my impact section of board. California State, Legislature, Senate. Proposition 6. -

Reach More of the Gay Market

Reach More of the Gay Market Mark Elderkin [email protected] (954) 485-9910 Evolution of the Gay Online Ad Market Concentration A couple of sites with reach Fragmentation Many sites with limited reach Gay Ad Network Aggregation 3,702,065 Monthly Gay Ad Network creates reach Unique Users (30-day Reach by Adify - 04/08) 1995 2000 2005 2010 2 About Gay Ad Network Gay Ad Network . The Largest Gay Audience Worldwide comScore Media Metrix shows that Gay Ad Network has amassed the largest gay reach in the USA and Health & Fitness abroad. (July 2008) Travel & Local . Extensive Network of over 200 LGBT Sites Entertainment Our publisher’s content is relevant and unique. We News & Politics do not allow chat rooms or adult content on our network. All publishers adhere to our strict editorial Women guidelines. Pop Culture . 100% Transparency for Impressions Delivered Parenting Performance reports show advertisers exactly where and when ads are delivered. Ad impressions are Business & Finance organic and never forced. Style . Refined Targeting or Run of Network Young Adult For media efficiency, campaigns can be site targeted, frequency-capped, and geo-targeted. For mass reach, we offer a run of network option. 3 Gay Ad Network: The #1 Gay Media Network Unique US Audience Reach comScore Media Metrix July 2008 . Ranked #1 by 750,000 comScore Media Metrix in Gay and Lesbian Category 500,000 . The fastest growing gay media property. 250,000 . The greatest 0 diversity and Gay Ad PlanetOut LOGOonline depth of content Network Network Network and audience The comScore July 2008 traffic report does not include site traffic segments. -

VOL 04, NUM 17.Indd

“WISCONSIN” FROM SEVENTH PAGE who may not realize that marriage is already heterosexually defined. To say that this is a gay marriage amendment is grossly erroneous. In State of fact, this proposed amendment seeks to make it permanently impossible for us to ever seek civil unions or gay marriage. The proposed ban takes away rights—rights we do not even have. If our Disunion opposition succeeds, this will be the first time that PERCENT OF discrimination has gone into our state constitution. EQUAL RIGHTS YEAR OF OPENLY But our opposition will not succeed. I have GAY/LESBIAN been volunteering and working on this campaign AMERICA’S FIRST OCTOBER 2006 VOL. 4 NO. 17 DEATH SENTENCE STUDENTS for three years not because I have an altruistic that are forced to drop nature, but because I hold the stubborn conviction for sodomy: 1625 out: that fairness can prevail through successfully 28 combating ignorance. If I had thought defeating YEAR THAT this hate legislation was impossible, there is no way NUMBER OF I would have kept coming back. But I am grateful AMERICA’S FIRST SODOMY LAW REPORTED HATE that I have kept coming back because now I can be CRIMES a part of history. On November 7, turn a queer eye was enacted: 1636 in 2004 based on towards Wisconsin and watch the tables turn on the sexual orientation: conservative movement. We may be the first state to 1201 defeat an amendment like this, but I’ll be damned if YEAR THE US we’ll be the last. • SUPREME COURT ruled sodomy laws DATE THAT JERRY unconstitutional: FALWELL BLAMED A PINK EDITORIAL 2003 9/11 on homosexuals, pagans, merica is at another crossroads in its Right now, America is at war with Iraq. -

February 2019 We Are Not Invisible: New

February 2019 We Are Not Invisible: New Exhibition Celebrates Survival and Resilience of Two-Spirit Community by J. Miko Thomas Two Spirit can be defined as an umbrella term for LGBTQ Native Americans — a pan-Indian term coined in the 1990s for use across the various languages of indigenous communities. Many tribal nations also give Two-Spirit people specific names and roles in their own cultures. A new exhibition that opened January 31 at the GLBT Historical Society Museum celebrates the survival and resilience of Two Spirits. “Two-Spirit Voices: Returning to the Circle” marks the 20th anniversary of Bay Area American Indian Two Spirits. BAAITS is an organization committed to activism and service for Two-Spirit people and their allies in the San Francisco Bay Area. It grew from the indigenous urban community out of a necessity to build spaces for queer Natives. It was inspired by Gay American Indians, founded in 1975, and the International Two-Spirit Gatherings held annually in the U.S. and Canada. The exhibition is co-curated by Roger Kuhn, Amelia Vigil and Ruth Villaseñor. Kuhn is a former chair of BAAITS and a member of the Porch Band of Creek Indians. Vigil is a Two-Spirit and Latinx performance artist and poet who currently chairs BAAITS. Villaseñor is a Chiricahua-Apache Mexican woman who identifies as Two Spirit; she serves on the board of BAAITs. Roger Kuhn responded to questions from History Happens. What impact has BAAITS had in the Two-Spirit, LGBTQ and native communities? For 20 years BAAITS has worked to recover and restore the role of Two- Spirit people in American Indian and First Nations communities. -

District Based Annual Report

SFAC Commissioners Fiscal Year 2009-2010 P.J. Johnston, President At Large Maya Draisin, Vice President Media Arts JD Beltran At Large Rene Bihan Landscape Architecture Through August 2009 Nínive Calegari Literary Arts Through March 2010 John Calloway Performing Arts (Music) Greg Chew At Large Leo Chow Architecture Amy Chuang Performing Arts (Music) Topher Delaney Visual Arts Through March 2010 Lorraine García-Nakata Literary Arts Astrid Haryati Landscape Architecture Sherene Melania Performing Arts (Dance) Jessica Silverman Visual Arts Barbara Sklar At Large Cass Calder Smith Architecture Sherri Young Performing Arts (Theater) Ron Miguel Ex Officio, President, Planning Commission San Francisco Arts Commission Annual Report 2010 on District-Based Programming and Impact Gavin Newsom Mayor Luis R. Cancel Director of Cultural Affairs FY 2009-2010 www.sfartscommission.org A letter from the President of the Arts Commission and the Director of Cultural Affairs We are pleased to present to the Board of Supervisors and other City leaders this annual report on the activities and grants supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission during fiscal year 2009- 2010. For the past four years, the Arts Commission has attempted to provide Supervisors and the citizens of San Francisco with a picture of the varied ways that our agency interacts with the public, supports artists and arts organizations, and enriches the quality of life in many neighborhoods throughout the City. Each year we strive to improve upon the quantitative data that we use to capture this rich and complex interaction between City funding and the cultural community, and this year we are pleased to introduce statistical highlights drawn from information provided by San Francisco-based arts organizations to the California Cultural Data Project (CDP). -

Queer Periodicals Collection Timeline

Queer Periodicals Collection Timeline 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Series I 10 Percent 13th Moon Aché Act Up San Francisco Newsltr. Action Magazine Adversary After Dark Magazine Alive! Magazine Alyson Gay Men’s Book Catalog American Gay Atheist Newsletter American Gay Life Amethyst Among Friends Amsterdam Gayzette Another Voice Antinous Review Apollo A.R. Info Argus Art & Understanding Au Contraire Magazine Axios Azalea B-Max Bablionia Backspace Bad Attitude Bar Hopper’s Review Bay Area Lawyers… Bear Fax B & G Black and White Men Together Black Leather...In Color Black Out Blau Blueboy Magazine Body Positive Bohemian Bugle Books To Watch Out For… Bon Vivant 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Bottom Line Brat Attack Bravo Bridges The Bugle Bugle Magazine Bulk Male California Knight Life Capitol Hill Catalyst The Challenge Charis Chiron Rising Chrysalis Newsletter CLAGS Newsletter Color Life! Columns Northwest Coming Together CRIR Mandate CTC Quarterly Data Boy Dateline David Magazine De Janet Del Otro Lado Deneuve A Different Beat Different Light Review Directions for Gay Men Draghead Drummer Magazine Dungeon Master Ecce Queer Echo Eidophnsikon El Cuerpo Positivo Entre Nous Epicene ERA Magazine Ero Spirit Esto Etcetera 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 -

MEDIA RELEASE for Immediate Release

View as webpage MEDIA RELEASE For immediate release June 10, 2021 MEDIA CONTACT Mark Sawchuk (415) 777-5455 ext. 8 [email protected] July LGBTQ History Programs Highlight the Leather & LGBTQ Cultural District and Curator Tour of Upcoming “Queeriosities” Exhibition San Francisco — The program series for July 2021 sponsored by the GLBT Historical Society will highlight a discussion with the District Manager of the LEATHER & LGBTQ Cultural District, Cal Callahan, and a preview curatorial tour of the GLBT Historical Society’s upcoming “Queeriosities” exhibition, which opens at the end of the month. All events take place online; registration is required for access to the video link. For more information, visit www.glbthistory.org. Queer Culture Club Catching Up With Cal Callahan Thursday, July 8 7:00–7:30 p.m. Online program Admission: free, $5 suggested donation GLBT Historical Society executive director Terry Beswick will interview Cal Callahan, the district manager of the LEATHER & LGBTQ Cultural District. Established in 2018, the district is one of three LGBTQ-related cultural districts in San Francisco, along with the Transgender District and the Castro LGBTQ Cultural District. This is the July installment of “Queer Culture Club,” our monthly series each second Thursday that focuses on LGBTQ people who are defining the queer culture of yesterday, today and tomorrow. Each month, Beswick interviews queer culture-makers, including authors, playwrights, historians, activists, artists and archivists, to learn about their work, process, inspirations, hopes and dreams. More information is available at https://bit.ly /3gcPSCB. Tickets are available at https://bit.ly/3vGk8Lr. Curator Tour Queeriosities: A Curator-Led Preview Friday, July 23 6:00–7:00 p.m. -

Bay Area Reporter, Volume 11, Number 17, 13 August 1981

I 528 15TH STREET, SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94103 TELEPHONE: 415/861-5019 VOL. XI NO. 17 AUGUST 13, 1981 SFPD Raid Hotel In the last several months close to two hundred people Guests and Staff in Uproar have paid $150 for the right to get, keep or look at the by Paul Lorch kicking down doors, physical¬ bodies which have become ly and verbally roughing up such a tourist attraction in the Residents of the Zee Hotel both staff and guests and Castro. This financial exercise were stilt reeling in shock this arresting over a dozen males was done at a gym formerly week over what they uniform¬ (although even at this point called “The Pump Room” on ly feel was a horror-filled vio¬ the Zee people still aren’t sure upper Market Street. lation of their lives. On Thurs¬ of exactly how many were day, August 6, shortly after booked, how many were sub¬ It seems the man who own¬ 5pm the Tenderloin hotel sequently released, or how ed the Pump Room decided to let the air out of the Pump “You have a building full of queers and crimi¬ Room and head South. This has left the owner of the nals and we 're going to get rid of them for you. ” building, through various legal procedures, with a really San Francisco Police Officer jazzy and well-equipped gym. at the Zee Hotel Thus, under the auspices of one Loran Lee there is now found itself awash in a sea of many are still in custody). The Bodyworks Gym where undercover police. -

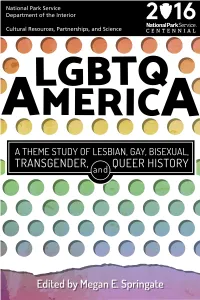

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PLACES Unlike the Themes section of the theme study, this Places section looks at LGBTQ history and heritage at specific locations across the United States. While a broad LGBTQ American history is presented in the Introduction section, these chapters document the regional, and often quite different, histories across the country. In addition to New York City and San Francisco, often considered the epicenters of LGBTQ experience, the queer histories of Chicago, Miami, and Reno are also presented. QUEEREST28 LITTLE CITY IN THE WORLD: LGBTQ RENO John Jeffrey Auer IV Introduction Researchers of LGBTQ history in the United States have focused predominantly on major cities such as San Francisco and New York City. This focus has led researchers to overlook a rich tradition of LGBTQ communities and individuals in small to mid-sized American cities that date from at least the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century. -

Gay and Lesbian Issues and Psychology Review

Gay and Lesbian Issues and Psychology Review Editors Damien W. Riggs & Vicki Crowley The Australian Psychological Society Ltd. ISSN 1833-4512 Gay and Lesbian Issues and Psychology Review Editor Damien W. Riggs, The University of Adelaide Editorial Board Graeme Kane, Eastern Drug and Alcohol Service Gordon A. Walker, Monash University Jim Malcom, The University of Western Sydney Robert Morris, Private practice Liz Short, Victoria University Brett Toelle, The University of Sydney Jane Edwards, Spencer Gulf Rural Health School Warrick Arblaster, Mental Health Policy Unit, ACT Murray Drummond, The University of South Australia General Information All submissions or enquires should be directed in the first instance to the Editor. Guidelines for submissions or for advertising within the Gay and Lesbian Issues in Psychology Review (‘the Review’) are provided on the final page of each issue. http://www.groups.psychology.org.au/glip/glip_review/ The Review is listed on Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory: http://www.ulrichsweb.com/ Aims and scope The Review is a peer-reviewed publication that is available online through the Australian Psychological Society website. Its remit is to encourage research that challenges the stereotypes and assumptions of pathology that have often inhered to research on lesbians and gay men (amongst others). The aim of the Review is thus to facilitate discussion over the direction of lesbian and gay psychology in Australia, and to provide a forum within which academics, practitioners and lay people may publish. The Review is open to a broad range of material, and especially welcomes research, commentary and reviews that critically evaluate the status quo in regards to lesbian and gay issues. -

HISTORY HAPPENS News from the GLBT Historical Society & the GLBT History Museum

HISTORY HAPPENS News From The GLBT Historical Society & The GLBT History Museum December 2013 On the Road: Loans, Traveling Exhibition Send GLBT History Across the Country and Beyond Join Donate Volunteer Learn More HOLIDAY GIFTS Library preservation associate Keith Duquette works on the layout of issues of The Ladder for the "Twice Militant" show at the Brooklyn Museum. From an exhibition in Berlin in the late 1990s to a new show in San Francisco, loans from the archives of the GLBT Historical Society have helped cultural Looking for that perfect institutions across the United States and beyond put queer history on display. And gift for the history buff in with the first traveling exhibition from The GLBT History Museum attracting visitors your life? Get the jump in Richmond, Va., the society is not only making artifacts available to curators on your holiday shopping elsewhere; it's also putting its own curatorial vision on the road. at The GLBT History Museum. The museum One of the society's earliest major loan agreements involved sending some 40 store offers exclusive t-shirts, mugs, totes, documents to the monumental "Goodbye to Berlin?" show organized in the whistles, magnets and German capital to mark the 100th anniversary of the homosexual emancipation cards with graphics from movement in 1997. Since then, numerous curators have borrowed materials from the archives of the GLBT the archives. The latest loans are currently featured in one exhibition on the far Historical Society. side of the U.S. and another just a few blocks from the archives: Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn, N.Y.): "Twice Militant: Lorraine Hansberry's Letters to The Ladder." For a show on African American playwright Lorraine Hansberry's GET INVOLVED correspondence with the pioneering lesbian magazine The Ladder, the Brooklyn Museum borrowed scarce issues of the publication from the Historical Society's periodicals collection.