10 Pop Artists on Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta Pedagogická

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta pedagogická Bakalářská práce VZESTUP AMERICKÉHO KOMIKSU DO POZICE SERIÓZNÍHO UMĚNÍ Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 University of West Bohemia Faculty of Education Undergraduate Thesis THE RISE OF THE AMERICAN COMIC INTO THE ROLE OF SERIOUS ART Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 Tato stránka bude ve svázané práci Váš původní formulář Zadáni bak. práce (k vyzvednutí u sekretářky KAN) Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracoval/a samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů informací. V Plzni dne 19. června 2012 ……………………………. Jiří Linda ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank to my supervisor Brad Vice, Ph.D., for his help, opinions and suggestions. My thanks also belong to my loved ones for their support and patience. ABSTRACT Linda, Jiří. University of West Bohemia. May, 2012. The Rise of the American Comic into the Role of Serious Art. Supervisor: Brad Vice, Ph.D. The object of this undergraduate thesis is to map the development of sequential art, comics, in the form of respectable art form influencing contemporary other artistic areas. Modern comics were developed between the World Wars primarily in the United States of America and therefore became a typical part of American culture. The thesis is divided into three major parts. The first part called Sequential Art as a Medium discusses in brief the history of sequential art, which dates back to ancient world. The chapter continues with two sections analyzing the comic medium from the theoretical point of view. The second part inquires the origin of the comic book industry, its cultural environment, and consequently the birth of modern comic book. -

American Pop Icons Christine Sullivan

I # -*-'- ,: >ss;«!«!«:»•:•:•:•:•: •••••• » - ••••••••••••# fi I»Z»Z , Z»Z»Z» m AMER1CANP0PIC0NS Guggenheim Hermitage museum Published on the occasion of the exhibition Design: Cassey L. Chou, with Marcia Fardella and American Pop Icons Christine Sullivan Guggenheim Hermitage Museum. Las Vegas Production: Tracy L. Hennige May15-November2,2003 Editorial: Meghan Dailey, Laura Morris Organized by Susan Davidson Printed in Germany by Cantz American Pop Icons © 2003 The Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation, Front cover (detail) and back cover: New York. All rights reserved. Roy Lichtenstein, Preparedness, 1968 (plate 16) Copyright notices for works of art reproduced in this book: © 2003 Jim Dine; © 2003 Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York; © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein; © 2003 Claes Oldenburg; © 2003 Robert Rauschenberg/Licensed by VAGA. New York; © 2003 James Rosenquist/Licensed by VAGA, New York; © 2003 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; © 2003 Tom Wesselmann/Licensed by VAGA, New York. Entries by Rachel Haidu are reprinted with permission from From Pop to Now: Selections from the Sonnabend Collection (The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, 2002). Entries by Jennifer Blessing and Nancy Spector are reprinted from Guggenheim Museum Collection: A to Z (Guggenheim Museum, 2001); Artist's Biographies (except Tom Wesselmann) are reprinted from Rendezvous: Masterpieces from the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Guggenheim Museums (Guggenheim Museum, 1998). isbn 0-89207-296-2 -

Jim Dine's Etchings

Jim Dine's etchings Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1978 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1817 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art JIM DINES ETCHINGS The Museum of Modern Art An exhibition organized by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, with the generous support of the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D.C., a federal agency About five years after they attended Ohio University in Athens together, Andrew Stasik invited his friend Jim Dine to make a print at Pratt Graphics Art Center in New York. A program at Pratt funded by the Ford Foundation had been established to encourage American artists to col laborate with professional European printers in the creation of lithographs and etchings. Even in the mid-twentieth century the word "etching" meant, to most people, the ubiquitous black-and-white views of famous buildings, homes, and landscapes, or to the connoisseur, the important images of Rembrandt and Whistler. Contemporary works by S. W. Hayter and his followers, because of the complex techniques utilized, were bet ter known by the generic term "intaglio" prints. After making a few litho graphs, Dine worked on his first intaglio prints in 1961 with the Dutch woman printmaker Nono Reinhold. They were simple drypoints of such familiar objects as ties, apples, and zippers. -

Norton Simon Museum Advance Exhibition Schedule 2016 All Information Is Subject to Change

Norton Simon Museum Advance Exhibition Schedule 2016 All information is subject to change. Please confirm details before publishing. Contact: Leslie Denk, Director of Public Affairs, [email protected] | 626-844-6941 Duchamp to Pop March 4–August 29, 2016 Many of the twentieth century’s greatest artists were influenced by one pivotal figure: Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). Duchamp to Pop uses the Norton Simon Museum’s collection and rich archives from two seminal exhibitions—New Painting of Common Objects from 1962 and Marcel Duchamp Retrospective from 1963—to illustrate Duchamp’s potent influence on Pop Art and the artists Andy Warhol, Jim Dine, Ed Ruscha and others. Drawing, Dreaming and Desire: Works on Paper by Sam Francis April 8–July 25, 2016 Drawing, Dreaming and Desire presents works on paper that explore the subject of erotica by the internationally acclaimed artist Sam Francis (1923– 1994). Renowned for his abstract, atmospheric and vigorously colored paintings, these intimate drawings—thoughts made visible, in pen and ink, acrylic and watercolor—relate to the genre of erotic art long practiced by artists in the West and the East. They resonate with significant moments in the artist’s biography, and reveal another aspect of his creative energy. This highly spirited but little known body of work, which ranges from the line drawings of the 1950s to the gestural, calligraphic brushstrokes of the 1980s, provides insight to a deeply personal side of the artist’s creative oeuvre. Dark Visions: Mid-Century Macabre September 2, 2016–January 16, 2017 The twentieth century produced some of the most distinctive, breakthrough art movements: Surrealism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art and Minimalism. -

Duchamp to Pop March 4–Aug

January 2016 Media Contacts: Leslie C. Denk | [email protected] | (626) 844-6941 Emma Jacobson-Sive | [email protected]| (323) 842-2064 Duchamp to Pop March 4–Aug. 29, 2016 Pasadena, CA—The Norton Simon Museum presents Duchamp to Pop, an exhibition that examines Marcel Duchamp’s potent influence on Pop Art and its leading artists, among them Andy Warhol, Jim Dine and Ed Ruscha. Approximately 40 artworks from the Museum’s exceptional collection of 20th-century art, along with a handful of loans, are brought together to pay tribute to the creative genius of Duchamp and demonstrate his resounding impact on a select group of artists born half a century later. The exhibition also presents materials from the archives of the Pasadena Art Museum (which later became the Norton Simon Museum) that pertain to two seminal exhibitions there—New Painting of Common Objects from 1962 and Marcel Duchamp Retrospective from 1963. L.H.O.O.Q. or La Joconde, 1964 (replica of 1919 original) by Marcel Duchamp © Succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2016 Marcel Duchamp In 1916, Duchamp (1887–1968) wrote to his sister, “I purchased this as a sculpture already made.” The artist was referring to his Bottlerack, and with this description he redefined what constituted a work of art—the readymade was born. The original Bottlerack was an unassisted readymade, meaning that it was not altered physically by the artist. The bottle rack was a functional object manufactured for the drying of glass bottles. Duchamp purchased it from a department store in Paris and brought the bottle rack into the art world to alter its meaning. -

Vija Celmins in California 1962-1981

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Winter 1-3-2020 Somewhere between Distance and Intimacy: Vija Celmins in California 1962-1981 Jessie Lebowitz CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/546 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Somewhere between Distance and Intimacy: Vija Celmins in California 1962-1981 by Jessie Lebowitz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2019 December 19, 2019 Howard Singerman Date Thesis Sponsor December 19, 2019 Harper Montgomery Date Signature of Second Reader Table of Contents List of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The Southern California Renaissance 8 Chapter 2: 1970s Pluralism on the West Coast 29 Chapter 3: The Modern Landscape - Distant Voids, Intimate Details 47 Conclusion 61 Bibliography 64 Illustrations 68 i List of Illustrations All works are by Vija Celmins unless otherwise indicated Figure 1: Time Magazine Cover, 1965. Oil on canvas, Private collection, Switzerland. Figure 2: Ed Ruscha, Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights, 1962. Oil, house paint, ink, and graphite pencil on canvas, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Figure 3: Heater, 1964. Oil on canvas, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Figure 4: Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1949. Oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Living Minnesota

Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title Opening date Closing date Living Minnesota Artists 7/15/1938 8/31/1938 Stanford Fenelle 1/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Grandma’s Dolls 1/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Parallels in Art 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Trends in Contemporary Painting 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Time-Off 1/4/1940 1/1/1940 Ways to Art: toward an intelligent understanding 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Letters, Words and Books 2/28/1940 4/25/1940 Elof Wedin 3/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Frontiers of American Art 3/16/1940 4/16/1940 Artistry in Glass from Dynastic Egypt to the Twentieth Century 3/27/1940 6/2/1940 Syd Fossum 4/9/1940 5/12/1940 Answers to Questions 5/8/1940 7/1/1940 Edwin Holm 5/14/1940 6/18/1940 Josephine Lutz 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Exhibition of Student Work 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Käthe Kollwitz 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title Opening date Closing date Paintings by Greek Children 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Jewelry from 1940 B.C. to 1940 A.D. 6/27/1940 7/15/1940 Cameron Booth 7/1/1940 ?/?/1940 George Constant 7/1/1940 7/30/1940 Robert Brown 7/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Portraits of Indians and their Arts 7/15/1940 8/15/1940 Mac Le Sueur 9/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Paintings and their X-Rays 9/1/1940 10/15/1940 Paintings by Vincent Van Gogh 9/24/1940 10/14/1940 Walter Kuhlman 10/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Marsden Hartley 11/1/1940 11/30/1940 Clara Mairs 11/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Meet the Artist 11/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Unpopular Art 11/7/1940 12/29/1940 National Art Week 11/25/1940 12/5/1940 Art of the Nation 12/1/1940 12/31/1940 Anne Wright 1/1/1941 ?/?/1941 Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title -

Journey Planet 22

THOR JP STARK CAP HAWKEYE BANNER WIDOW JOURNEY PLANET 22 i Cover - Photo shoot by Richard Man (http://richardmanphoto.com) Journey Models - Captain America - Karen Fox Planet Thor - Rhawnie Pino Tony Stark/Iron Man - Jennifer Erlichman Hawkeye - Sahrye Cohen Banner - Linda Wenzelburger Editors Black Widow - Hal Rodriguez James Bacon Page 1 - Real Life Costumed Heroes Purple Reign and Phonenix Jones! Page 3 - Editorials - James, Linda, Chris (Photo by Jean Martin, Art from Mo Starkey) Aurora Page 7 -Getting to Know the Sentinel of Liberty: Two Books about Captain America Celeste by Chuck Serface Chris Garcia Page 13 - Resurrection and Death in 69 Pages- Simonson and Goodwin’s Manhunter by Joel Zakem Page 16 - Days of Wonder, Trailblazers in UK and Irish Comics Fandom by James Bacon Linda Page 22 - My Imaginary Comic Book Company by Chris Garcia Wenzelburger Page 25 - Crossing Over: Five Superhero Books for Sci-Fi Fans By Donna Martinez P a g e 2 7 - T h e B - Te a m b y R e i d Va n i e r ( fir s t a p p e a r e d a t http://modernmythologies.com/2014/09/10/the-b-team/) Page 30 - Andy Warhol in Miracleman #19 by Padraig O’Mealoid Page 35 - Warhol & The Comics by James Bacon Page 43 - An Interview with Mel Ramos Page 45 - Superman by Hillary Pearlman-Bliss Page 46 - Playing at Heroes - Superheroic RPGs and Me by Chris Garcia Page 49 - Misty Knight by Sierra Berry Page 50 - Comic Book Movies and Me by Helena Nash Page 53 - Getting to Know the Princess of Power: Four Biographies of Wonder Woman by Chuck Serface Page 62 - The Mighty World of -

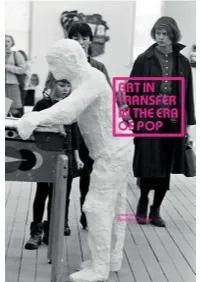

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

Tom Wesselmann Born in 1931 in Cincinnati, OH, USA Biography Died in 2004

Tom Wesselmann Born in 1931 in Cincinnati, OH, USA Biography Died in 2004 Education 1959 The Cooper Union, New York, USA 1956 Psychology BA, University of Cincinnati, USA 1951 Hiram College, Ohio, USA Solo Exhibitions 2020 Tom Wesselmann 'Smoker #27', Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany 2019 Almine Rech Gallery, London, UK 2018 'La Promesse du Bonheur', Le Nouveau Musée National de Monaco, Ville Paloma, Monaco 2017 'Tom Wesselmann', Almine Rech Gallery, London, UK ‘Tom Wesselmann – Telling It Like It Is’, Vedovi Gallery, Brussels, Belgium ‘Bedroom Paintings’, Gagosian Gallery, London, UK 2016 ‘A Different Kind of Woman’, Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, France ‘Collages 1959-1964’, David Zwirner Gallery, London, UK Mitchell-Innes and Nash Gallery, New York, USA 'Early Works', Van de Weghe Gallery, New York, USA 2015 'A Line to Greatness', Galerie Gmurzynska, St. Moritz, Switzerland 2014 ‘Beyond Pop Art; A Tom Wesselmann Retrospective’, Denver Art Museum, Dever, USA 64 rue de Turenne, 75003 Paris ‘Beyond Pop Art; A Tom Wesselmann Retrospective’, Cincinnati Art Museum, USA 18 avenue de Matignon, 75008 Paris [email protected] - 2013 Abdijstraat 20 rue de l’Abbaye ‘Beyond Pop Art; A Tom Wesselmann Retrospective’, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, USA Brussel 1050 Bruxelles ‘Still Life, Nude, Landscape: The Late Prints ‘, Alan Cristea Gallery, London [email protected] - Grosvenor Hill, Broadbent House 2012 W1K 3JH London ‘Beyond Pop Art: A Tom Wesselmann Retrospective’, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, [email protected] -

JIM DINE Jim Dine Was Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1935. He Grew

JIM DINE Jim Dine was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1935. He grew up in what he regards as the beautiful landscape of the Midwest, a tone and time to which he returns constantly. He studied at the University of Cincinnati and the Boston Museum School and received his B.F.A. from Ohio University in 1957. Dine, renowned for his wit and creativity as a Pop and Happenings artist, has a restless, searching intellect that leads him to challenge himself constantly. Over four decades, Dine has produced more than three thousand paintings, sculptures, drawings, and prints, as well as performance works, stage and book designs, poetry, and even music. His art has been the subject of numerous individual and group shows and is in the permanent collections of museums around the world. Dine's earliest art—Happenings and an incipient form of pop art—emerged against the backdrop of abstract expressionism and action painting in the late 1950s. Objects, most importantly household tools, began to appear in his work at about the same time. A hands-on quality distinguished these pieces, which combine elements of painting, sculpture, and installation, as well as works in various other media, including etching and lithography. Through a restricted range of obsessive images, which continue to be reinvented in various guises— bathrobe, heart, outstretched hand, wrought-iron gate, and Venus de Milo—Dine presents compelling stand-ins for himself and mysterious metaphors for his art. The human body conveyed through anatomical fragments and suggested by items of clothing and other objects, emerges as one of Dine's most urgent subjects. -

4 on the Construction of Pop Art When American Pop Arrived in Stockholm in 1964

4 On the Construction of Pop Art When American Pop Arrived in Stockholm in 1964 Annika Öhrner 127 It seems that there are chances that this can be made in 1964 already. We have seen a lot of the followers here and there is a risk that the whole “pop” thing will be misunderstood in Europe, if we see all the followers before we see the originals. (I would be glad if you could help us with these plans, and speak to the artists about them.) Pontus Hultén to Richard Bellamy1 Art historical accounts have often relied on the idea of American pop art arriving in Europe in a sudden, almost aggressive act with immediate impact on the local milieu. It has been described as a more or less effortless conquest of the European art scene, accomplished through the power of the strong images themselves, after the pop music and the film industry had paved the way. It was and often continues to be claimed that pop art’s way of bridging the gap between high and low culture, while incorporating images and symbols from American everyday life into art, as well as pop art’s role in the radical redrawing of the geography of the Western art world were important factors for this influence. Authors such as Irving Sandler, Serge Guilbault, and Catherine Dossier have relied on different historical models of explanation of how America conquered Europe with 1 Letter from Pontus Hultén of the Moderna Museet to Richard Bellamy at the Green Gal- lery, 23 October 1963; in the archive of the Moderna Museet, Stockholm.