WHY the BLOCKCHAIN NEEDS the LAW Kevin Werbach†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Bar Association Business Law Section Committee on Derivatives and Futures Law

American Bar Association Business Law Section Committee on Derivatives and Futures Law Winter Meeting 2018 Naples, Florida Friday, January 19, 2018 10:15 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. NEW PRODUCTS / FINANCIAL TECHNOLOGY Moderator for the Program: Conrad G. Bahlke, Willkie Farr &Gallagher LLP Speakers: Geoffrey F. Aronow, Sidley Austin LLP Debra W. Cook, Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation Katherine Cooper, Law Office of Katherine Cooper Isabelle Corbett, R3 David Lucking, Allen & Overy LLP Brian D. Quintenz, Commissioner, U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission ABA BUSINESS LAW SECTION DERIVATIVES & FUTURES LAW COMMITTEE 2018 WINTER MEETING NEW PRODUCTS / FIN TECH PANEL 2017 Developments in US Regulation of Virtual Currencies and Related Products: Yin and Yang January 5, 2018 By Katherine Cooper1 2017 was a year during which virtual currencies began to move into the mainstream financial markets. This generated significant legal and regulatory developments as U.S. regulators faced numerous novel products attempting to blend the old with the new. Although facing so many novel issues, the regulators’ responses tell a familiar story of the struggle to balance the yin of customer protection with the yang of encouraging financial innovation and competition. Below is a summary of 2017 developments from the SEC, CFTC, OCC, FinCEN and the States. I. Securities and Exchange Commission a. Bitcoin Exchange-Traded Products A number of sponsors of proposed Bitcoin exchange traded products had applications for approval pending before the Securities and Exchange Commission at the beginning of 2017. In March 2017, the SEC rejected a proposal backed by Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss.2 The Bats Exchange proposed a rule amendment which would list the shares of the Winklevoss Bitcoin Trust for trading. -

Examining the Lightning Network on a Protocol Level

Examining the Lightning network on a protocol level Rene Pickhardt (Data Science Consultant) https://www.rene-pickhardt.de & https://twitter.com/renepickhardt München 19.7.2018 I've been told I should start any talk with something everybody in the audience should know A standard Bitcoin Transaction has 6 data fields ( The following is a brief summary of https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Transaction#Input ) ● Version number (4 Bytes) ● In-Counter (1-9 Bytes) ● List of inputs (depending on the Value of <In-Counter>) ● Out-Counter (1-9 Bytes) ● List of Outputs (depending on the Value of <Out-Counter>) ● Lock_time (4 Bytes) ( Bitcoin Transaction with 3 inputs and 2 outputs Data consists mainly of executable scripts! A chain of Bitcoin Transactions with 3 UTXO ● Outputs are references by the inputs ● The Script in the output defines how the transaction can be spent ● Owning Bitcoins means being able to spend the output of an unspent transaction ○ Provide an input script ○ Concatenate it with with some outputscript of an unspent transaction ○ The combined Script needs to evaluate to True Spending a Pay-to-PubkeyHash (standard TX) ● ScriptPubKey (aka the Output Script) ○ OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG ● ScriptSig: (aka the Input Script) ○ <sig> <pubKey> ● Explainations ○ OP_CODES are the instructions of the script language within Bitcoin ○ <data> is depicted like html tags with lesser than and greater than signs ○ The complete script is concatenated as Input || Output and then being executed on a Stack machine <sig> <pubKey> -

CASP) Software-Only, Ledger Agnostic, Platform Agnostic, Crypto Agile Bank-Grade Security for Crypto Assets

Protect Your Crypto Assets with Unbound’s Crypto Assets Security Platform (CASP) Software-Only, Ledger Agnostic, Platform Agnostic, Crypto Agile Bank-Grade Security for Crypto Assets Mathematically proven security Cryptography is one of the foundational security elements used by guarantee – the key material never organizations to protect sensitive data, transactions, services and identities. exists in the clear throughout its At the core of any cryptography implementation is the management of lifecycle including creation, in-use cryptographic keys and their protection from compromise and misuse. and at-rest With crypto assets, the protection of private keys is top priority, since the Any currency, any ledger, any private key is used to sign each transaction. It is therefore mandatory platform, any client to keep the key secure – not only from compromise, but also from any Programmatically derived malicious usage – as it takes only one fraudulent transaction (i.e. a single sign addresses (BIP 32/44) that are operation, to empty a wallet). cryptographically protected Backed by proven mathematical guarantees of security, Unbound’s Crypto Stronger and more flexible than Asset Security Platform (CASP) provides its customers with a software-only multi-signature – ledger-agnostic support of flexible quorum security platform that is as safe as hardware. With CASP, one can fully manage structures, any number of human the keys’ lifecycle, define cryptographically-based approval policies, while and/or servers, internal and supporting any currency, any ledger, any platform and any client type. external, that are required to sign a transaction Any Currency, Any Ledger, Any Platform Infinite scalability – easily scale capacity when and where it is Traditionally, securing the keys and secrets that guard the organizations’ most needed valuable assets required the use of dedicated hardware, such as hardware Intuitive and easy to use SDK – security modules (HSMs) and smartcards. -

Rev. Rul. 2019-24 ISSUES (1) Does a Taxpayer Have Gross Income Under

26 CFR 1.61-1: Gross income. (Also §§ 61, 451, 1011.) Rev. Rul. 2019-24 ISSUES (1) Does a taxpayer have gross income under § 61 of the Internal Revenue Code (Code) as a result of a hard fork of a cryptocurrency the taxpayer owns if the taxpayer does not receive units of a new cryptocurrency? (2) Does a taxpayer have gross income under § 61 as a result of an airdrop of a new cryptocurrency following a hard fork if the taxpayer receives units of new cryptocurrency? BACKGROUND Virtual currency is a digital representation of value that functions as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value other than a representation of the United States dollar or a foreign currency. Foreign currency is the coin and paper money of a country other than the United States that is designated as legal tender, circulates, and is customarily used and accepted as a medium of exchange in the country of issuance. See 31 C.F.R. § 1010.100(m). - 2 - Cryptocurrency is a type of virtual currency that utilizes cryptography to secure transactions that are digitally recorded on a distributed ledger, such as a blockchain. Units of cryptocurrency are generally referred to as coins or tokens. Distributed ledger technology uses independent digital systems to record, share, and synchronize transactions, the details of which are recorded in multiple places at the same time with no central data store or administration functionality. A hard fork is unique to distributed ledger technology and occurs when a cryptocurrency on a distributed ledger undergoes a protocol change resulting in a permanent diversion from the legacy or existing distributed ledger. -

Linking Wallets and Deanonymizing Transactions in the Ripple Network

Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies ; 2016 (4):436–453 Pedro Moreno-Sanchez*, Muhammad Bilal Zafar, and Aniket Kate* Listening to Whispers of Ripple: Linking Wallets and Deanonymizing Transactions in the Ripple Network Abstract: The decentralized I owe you (IOU) transac- 1 Introduction tion network Ripple is gaining prominence as a fast, low- cost and efficient method for performing same and cross- In recent years, we have observed a rather unexpected currency payments. Ripple keeps track of IOU credit its growth of IOU transaction networks such as Ripple [36, users have granted to their business partners or friends, 40]. Its pseudonymous nature, ability to perform multi- and settles transactions between two connected Ripple currency transactions across the globe in a matter of wallets by appropriately changing credit values on the seconds, and potential to monetize everything [15] re- connecting paths. Similar to cryptocurrencies such as gardless of jurisdiction have been pivotal to their suc- Bitcoin, while the ownership of the wallets is implicitly cess so far. In a transaction network [54, 55, 59] such as pseudonymous in Ripple, IOU credit links and transac- Ripple [10], users express trust in each other in terms tion flows between wallets are publicly available in an on- of I Owe You (IOU) credit they are willing to extend line ledger. In this paper, we present the first thorough each other. This online approach allows transactions in study that analyzes this globally visible log and charac- fiat money, cryptocurrencies (e.g., bitcoin1) and user- terizes the privacy issues with the current Ripple net- defined currencies, and improves on some of the cur- work. -

Bitcoin Tumbles As Miners Face Crackdown - the Buttonwood Tree Bitcoin Tumbles As Miners Face Crackdown

6/8/2021 Bitcoin Tumbles as Miners Face Crackdown - The Buttonwood Tree Bitcoin Tumbles as Miners Face Crackdown By Haley Cafarella - June 1, 2021 Bitcoin tumbles as Crypto miners face crackdown from China. Cryptocurrency miners, including HashCow and BTC.TOP, have halted all or part of their China operations. This comes after Beijing intensified a crackdown on bitcoin mining and trading. Beijing intends to hammer digital currencies amid heightened global regulatory scrutiny. This marks the first time China’s cabinet has targeted virtual currency mining, which is a sizable business in the world’s second-biggest economy. Some estimates say China accounts for as much as 70 percent of the world’s crypto supply. Cryptocurrency exchange Huobi suspended both crypto-mining and some trading services to new clients from China. The plan is that China will instead focus on overseas businesses. BTC.TOP, a crypto mining pool, also announced the suspension of its China business citing regulatory risks. On top of that, crypto miner HashCow said it would halt buying new bitcoin mining rigs. Crypto miners use specially-designed computer equipment, or rigs, to verify virtual coin transactions. READ MORE: Sustainable Mineral Exploration Powers Electric Vehicle Revolution This process produces newly minted crypto currencies like bitcoin. “Crypto mining consumes a lot of energy, which runs counter to China’s carbon neutrality goals,” said Chen Jiahe, chief investment officer of Beijing-based family office Novem Arcae Technologies. Additionally, he said this is part of China’s goal of curbing speculative crypto trading. As result, bitcoin has taken a beating in the stock market. -

On the Relationship of Cryptocurrency Price with US Stock and Gold Price Using Copula Models

mathematics Article On the Relationship of Cryptocurrency Price with US Stock and Gold Price Using Copula Models Jong-Min Kim 1 , Seong-Tae Kim 2 and Sangjin Kim 3,* 1 Statistics Discipline, University of Minnesota at Morris, Morris, MN 56267, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Mathematics, North Carolina A&T State University, Greensboro, NC 27411, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Management and Information Systems, Dong-A University, Busan 49236, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: This paper examines the relationship of the leading financial assets, Bitcoin, Gold, and S&P 500 with GARCH-Dynamic Conditional Correlation (DCC), Nonlinear Asymmetric GARCH DCC (NA-DCC), Gaussian copula-based GARCH-DCC (GC-DCC), and Gaussian copula-based Nonlinear Asymmetric-DCC (GCNA-DCC). Under the high volatility financial situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic occurrence, there exist a computation difficulty to use the traditional DCC method to the selected cryptocurrencies. To solve this limitation, GC-DCC and GCNA-DCC are applied to investigate the time-varying relationship among Bitcoin, Gold, and S&P 500. In terms of log-likelihood, we show that GC-DCC and GCNA-DCC are better models than DCC and NA-DCC to show relationship of Bitcoin with Gold and S&P 500. We also consider the relationships among time-varying conditional correlation with Bitcoin volatility, and S&P 500 volatility by a Gaussian Copula Marginal Regression (GCMR) model. The empirical findings show that S&P 500 and Gold price are statistically significant to Bitcoin in terms of log-return and volatility. -

IFRS: Accounting for Crypto-Assets

IFRS (#) Accounting for crypto-assets Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. What are crypto-assets? 2 2.1. Cryptocurrencies 3 2.2. Tokens (crypto-assets other than cryptocurrencies) 5 3. Accounting for crypto-assets 10 3.1. Selected activities of standard setters 10 3.2. Special situations 13 3.3. Conclusion 15 4. Supporting details 16 5. Contacts 21 1 Introduction Crypto-assets experienced a breakout year in 2017. Cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin and ether, have seen their prices surge as the public’s YoYj]f]kk`Ykaf[j]Yk]\$Yf\ÕfYf[aYdeYjc]lhYjla[ahYflk`Yn]l`mk af[j]Ykaf_dqlmjf]\l`]ajYll]flagflgl`]h`]fge]fgf&KaemdlYf]gmkdq$ a wave of new crypto-asset issuance has been sweeping the start-up fundraising world, sparking the interest of regulators in the process. 9[[gmflYflk`Yn]l`mk^YjZ]]ffglYZd]Zql`]ajj]dYlan]YZk]f[]^jge l`YlfYjjYlan]&H]j`Yhk$egklfglYZd]akl`]^Y[ll`Yll`]9mkljYdaYf 9[[gmflaf_KlYf\Yj\k:gYj\ 99K:!`YkkmZeall]\Y\ak[mkkagfhYh]j gfÉ\a_alYd[mjj]f[a]kÊlgl`]Afl]jfYlagfYd9[[gmflaf_KlYf\Yj\k :gYj\ A9K:!$Yf\l`]9[[gmflaf_KlYf\Yj\k:gYj\g^BYhYf 9K:B! `Ykakkm]\Yf]phgkmj]\jY^l^gjhmZda[[gee]flgfY[[gmflaf_^gj “virtual currencies”.1AfY\\alagf$l`]A9K:\ak[mkk]\[]jlYaf^]Ylmj]kg^ ljYfkY[lagfkafngdnaf_\a_alYd[mjj]f[a]k\mjaf_alke]]laf_afBYfmYjq *()0$Yf\oadd\ak[mkkaf^mlmj]o`]l`]jlg[gee]f[]Yj]k]Yj[`hjgb][l in this area.1 L`akYdkg`a_`da_`lkl`]dY[cg^YklYf\Yj\ar]\[jqhlg%Ykk]llYpgfgeq$ o`a[`eYc]kal\a^Õ[mdllg\]l]jeaf]l`]Yhhda[YZadalqg^klYf\Yj\k]ll]jkÌ hmZdak`]\h]jkh][lan]k&>mjl`]jegj]$\m]lgl`]\an]jkalqYf\hY[]g^ affgnYlagfYkkg[aYl]\oal`[jqhlg%Ykk]lk$l`]^Y[lkYf\[aj[meklYf[]k g^]Y[`af\ana\mYd[Yk]oadd\a^^]j$eYcaf_al\a^Õ[mdllg\jYo_]f]jYd [gf[dmkagfkgfl`]Y[[gmflaf_lj]Yle]fl& <]khal]l`]eYjc]lÌkaf[j]Ykaf_dqmj_]flf]]\^gjY[[gmflaf__ma\Yf[]$ l`]j]`Yn]Z]]ffg^gjeYdhjgfgmf[]e]flkgfl`aklgha[lg\Yl]& Afl`akj]hgjl$o]YaelgÕjklZja]Öqafljg\m[][jqhlg[mjj]f[a]kYf\ gl`]jlqh]kg^[jqhlg%Ykk]lk&L`]f$o]\ak[mkkkge]g^l`]j][]fl activities by accounting standard setters in relation to crypto-assets. -

Crypto-Asset Markets: Potential Channels for Future Financial Stability

Crypto-asset markets Potential channels for future financial stability implications 10 October 2018 The Financial Stability Board (FSB) is established to coordinate at the international level the work of national financial authorities and international standard-setting bodies in order to develop and promote the implementation of effective regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies. Its mandate is set out in the FSB Charter, which governs the policymaking and related activities of the FSB. These activities, including any decisions reached in their context, shall not be binding or give rise to any legal rights or obligations under the FSB’s Articles of Association. Contacting the Financial Stability Board Sign up for e-mail alerts: www.fsb.org/emailalert Follow the FSB on Twitter: @FinStbBoard E-mail the FSB at: [email protected] Copyright © 2018 Financial Stability Board. Please refer to: www.fsb.org/terms_conditions/ Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Primary risks in crypto-asset markets ................................................................................. 5 2.1 Market liquidity risks ............................................................................................... 5 2.2 Volatility risks ......................................................................................................... -

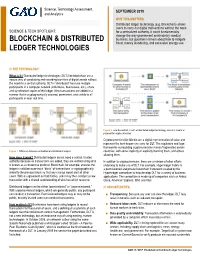

Blockchain & Distributed Ledger Technologies

Science, Technology Assessment, SEPTEMBER 2019 and Analytics WHY THIS MATTERS Distributed ledger technology (e.g. blockchain) allows users to carry out digital transactions without the need SCIENCE & TECH SPOTLIGHT: for a centralized authority. It could fundamentally change the way government and industry conduct BLOCKCHAIN & DISTRIBUTED business, but questions remain about how to mitigate fraud, money laundering, and excessive energy use. LEDGER TECHNOLOGIES /// THE TECHNOLOGY What is it? Distributed ledger technologies (DLT) like blockchain are a secure way of conducting and recording transfers of digital assets without the need for a central authority. DLT is “distributed” because multiple participants in a computer network (individuals, businesses, etc.), share and synchronize copies of the ledger. New transactions are added in a manner that is cryptographically secured, permanent, and visible to all participants in near real time. Figure 2. How blockchain, a form of distributed ledger technology, acts as a means of payment for cryptocurrencies. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are a digital representation of value and represent the best-known use case for DLT. The regulatory and legal frameworks surrounding cryptocurrencies remain fragmented across Figure 1. Difference between centralized and distributed ledgers. countries, with some implicitly or explicitly banning them, and others allowing them. How does it work? Distributed ledgers do not need a central, trusted authority because as transactions are added, they are verified using what In addition to cryptocurrencies, there are a number of other efforts is known as a consensus protocol. Blockchain, for example, ensures the underway to make use of DLT. For example, Hyperledger Fabric is ledger is valid because each “block” of transactions is cryptographically a permissioned and private blockchain framework created by the linked to the previous block so that any change would alert all other Hyperledger consortium to help develop DLT for a variety of business users. -

BLOCKCHAIN REVOLUTION: Surviving and Thriving in the 2Nd Era of the Internet

BLOCKCHAIN REVOLUTION: Surviving and Thriving in the 2nd Era of the Internet Alex Tapscott TWITTER: @alextapscott Swiss Re January 23rd, 2017 © 2016 Don Tapscott and Alex Tapscott. All Rights Reserved. The Technological Revolution mobility social big web data internet machine of things learning the cloud drones & robotics 2 | © 2016 The Tapscott Group. All Rights Reserved. The Technological Revolution mobility social big web data internet BLOCKCHAIN machine of things learning the cloud drones & robotics 3 | © 2016 The Tapscott Group. All Rights Reserved. The Internet of Information Web Photos Sites Word INFORMATION PDFs Docs PPT Voice Slides 4 | © 2016 The Tapscott Group. All Rights Reserved. The Internet of Information ▶ The Internet of Value Social Reputation Capital Intellectual Money property Loyalty Attestations Identity points ASSETS Contracts Deeds Carbon credits Energy ASSETS Coupons Other Financial Assets Bonds Premiums Music Art Votes Stocks Other Futures Receivables Swaps IOUs Visual Art Film 5 | © 2016 The Tapscott Group. All Rights Reserved. The Middleman 6 | © 2016 The Tapscott Group. All Rights Reserved. BLOCKCHAIN: The Second Era of the Internet 7 | © 2016 The Tapscott Group. All Rights Reserved. Just Another Block in the Chain 1 2 3 4 5 Block 53 Block50.dat Block51.dat Previous Block52.dat block: 00000zzxvzx5 Timestamp Proof of work: 00000090b41b 04.19.2016.09.14.5 x 3 Block53.dat Transaction: 94lxcv14 Community Reference to Distributed ledger New blocks added Permanent validation previous blocks time-stamp 8 | © 2016 The Tapscott Group. All Rights Reserved. 9 | © 2016 The Tapscott Group. All Rights Reserved. 10 | © 2016 The Tapscott Group. All Rights Reserved. Seven Transformations for a Prosperous World 1. -

Deviant Decentralized Exchange

DDEEVVXX Deviant Decentralized Exchange A hybrid exchange leveraging Smartcoins on the Bitshares (BTS) blockchain. CONTENTS 03 What is the current landscape for trading crypto assets? 05 Centralized Exchanges 08 Decentralized Exchanges 11 Hybrid Exchanges 13 DEVX Platform 14 Platform Overview 16 DEVX Smart Coin 17 DEVX off-chain engine - The DEVX Transient Protocol (DEVTP) 19 Trading Process 25 What is the status of development / roadmap for these innovations? 26 DEVX Team 03 Crypto assets are here to stay. According to Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, Bitcoin and WHAT IS THE blockchain will be the next major IT revolution, and will achieve full CURRENT potential in a decade. According to LANDSCAPE FOR Paypal co-founder Peter Thiel, Bitcoin is the next Digital Gold. TRADING CRYPTO Since Bitcoin’s release in 2009, 1,622 altcoin variants have been issued. ASSETS? 2018 has already broken all records with 345 Initial Coin Offerings, and over US$ 7.7 billion of capital raised. DEVX the next revolution 04 Growth in the number of crypto assets has also driven an increase in crypto asset trading, in order to satisfy the requirements of the increasingly numerous universe of holders, investors, arbitrageurs, market makers, speculators and hedgers. There are presently more than 500 crypto asset exchanges to bring together buyers and sellers, where crypto assets are traded for either different digital currencies, or for other assets such as conventional fiat money. These exchanges operate mostly outside Western countries, and range from fully-online platforms to bricks-and-mortar businesses. Currently, almost two thirds of all daily global crypto asset trading volume results from activity on just ten of these exchanges.