Nepal Joint Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Januar – März 2018) Zusammengestellt Von Karl-Heinz Krämer [Auszug Aus Dem Literatur-Gesamtverzeichnis Von Nepal Research]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9475/januar-m%C3%A4rz-2018-zusammengestellt-von-karl-heinz-kr%C3%A4mer-auszug-aus-dem-literatur-gesamtverzeichnis-von-nepal-research-39475.webp)

Januar – März 2018) Zusammengestellt Von Karl-Heinz Krämer [Auszug Aus Dem Literatur-Gesamtverzeichnis Von Nepal Research]

WISSENSCHAFTLICHE ARBEITEN UND AUSGEWÄHLTE PRESSEARTIKEL (Januar – März 2018) zusammengestellt von Karl-Heinz Krämer [Auszug aus dem Literatur-Gesamtverzeichnis von Nepal Research] Aase, Tor Halfden. 2017. Are doomsday scenarios best seen as failed predictions or political detonators? The case of the ‘Theory of Himalayan Environmental Degradation’. The Geographical Journal of Nepal 10: 1-14 Acharya, Bhanu Bhakta. 2018. Calling for press freedom: Nepal is still a long way from complete press freedom, and all stakeholders need to speak against violations. The Kathmandu Post, 17 January 2018 Acharya, Bhanu Bhakta. 2018. Danger zones for journalists. República, 4 January 2018 Acharya, Deepak. 2018. Tune into radio: Role of mass medium in Nepal. The Himalayan Times, 13 February 2018 Acharya, Haribol. 2018. Invisible thieves: Recent cyber-attacks have shown that Nepali banks need to keep up with technology. The Kathmandu Post, 11 January 2018 Acharya, Keshav K.. 2016. Determinants of Community Governance for Effective Basic Service Delivery in Nepal. Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 10:166-201 Acharya, Keshav K.. 2016. Impaired Governance: Limiting Communities’ Access to Service Delivery System in Nepal. Himalayan Journal of Sociology & Anthropology 7 : 40-74 Acharya, Keshav K.. 2017. Evaluating Institutional Capability of Nepali Grassroots Organizations for Service Delivery Functions. Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 11:60-95 Acharya, Sushant / Upreti, Bishnu Raj. 2015. Equity, Inclusion and Confict in Community Based Forest Management: A Case of Salghari Community Forest in Nepal. Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 9:209-223 Adhikari, Aditya. 2018. The legacies of the People’s War: Twelve years after the war, the Maoists are caught between an unviable utopianism and mere survivalism. -

And Alternative Schooling Program

VDC Workshop for ASP implementation from CASP experience Workshop Report Activity: VDC workshop on ASP Implementation rom CASP Experience Dates: 21st June 2009 (7 ASAR 2066) Venue: WTC, Tripureshwor, Kathmandu Hosted by: NFEC/JICA/CASP/ DEO/DDC 1 VDC workshop on ASP Implementation rom CASP Experience A REPORT Background of the Workshop Why Alternative Provision of Education is necessary in Nepal? Despite 85 years since educational promotion programs were launched in Nepal, formal education, which had been provided by GoN, remained incomplete. There are still a considerable number of school-aged children who cannot or do not go to school despite the governmental effort to make primary education universal under the Tenth Five-Year plan (2002-2007). About 280,000 of children are out of school, called “the hardest to reach group”. Meanwhile, Nepal government has been committed to international agreement to reach Education for All (EFA) goal (see The Box of “What is Education for All”?) namely after 2000. Particularly for children the main goal is for all to access to and complete, free and compulsory primary education of good quality. There are two major obstacles to prevent school-aged children from schooling, eventually making them Out–of-School Children. The first obstacle is for especially those living in remote villages situated in the middle mountainous place and the high place in the Himalaya Mountain. For these children, School Outreach Program (SOP) has been conducted. SOP offers small classes near village for the first to third grade students who cannot go to primary school. After the end of the third grade children will be transferred to formal schools that are normally far from the village they are live. -

OM DEVELOPMENT BANK LIMITED Chipledhunga, Pokhara Bonus Tax List for 17.69%(F/Y 073/74) S.No

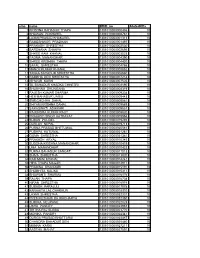

OM DEVELOPMENT BANK LIMITED Chipledhunga, Pokhara Bonus Tax List for 17.69%(F/Y 073/74) S.No. BOID/H.No. Name Type Tax Amount 1 1301060000362660 SUNIL KUMAR GOSHALI D-Promoter 64355.77 2 1301060000371411 LAXMI PALIKHE D-Promoter 22115.38 3 1301060000646704 POONAM GOSHALI D-Promoter 44230.77 4 1301080000020049 DIPAK RAJ SIGDEL D-Promoter 20702.65 5 1301540000004289 Kamal Raj Sapkota D-Promoter 44581.96 6 1301370000016117 Ganesh Kumar Pradhan D-Promoter 5881.81 7 1301060000154626 BINA GURUNG D-Promoter 26538.46 8 1301220000164810 JIGYASU PRADHAN D-Promoter 40098.73 9 1301020000237174 K.N HOLDINGS PVT. LTD D-Promoter 79291.61 10 1301040000006129 PRATAP KUMAR SHRESTHA D-Public 176.92 11 1301040000089785 SANBIRA GIRI D-Public 597.12 12 1301040000156887 KANHAIYA KIRAN SHRESTHA D-Public 442.31 13 1301060000014837 GAUTAM PRASAD PRAJAPATI D-Public 112.35 14 1301060000019909 JAG BAHADUR PUN D-Public 353.85 15 1301060000020644 NAB RAJ KHADKA D-Public 88.46 16 1301060000021384 SUBODH TAMRAKAR D-Public 450.27 17 1301060000027641 KALIDAS POUDEL D-Public 221.15 18 1301060000062940 RAKESH SHRISH D-Public 44.23 19 1301060000145803 BAIKUNTHA LAL RANJITKAR D-Public 353.85 20 1301060000255806 MOTI KUMAR SHRESTHA D-Public 8.85 21 1301060000266869 RABIN SHRESTHA D-Public 176.92 22 1301060000436242 KAMAL PRASAD PYAKURYAL D-Public 176.92 23 1301060000436276 SANJESH GURUNG D-Public 8.85 24 1301060000492798 JANAKI TAJHYA D-Public 17.69 25 1301060000492916 ROSHAN JOSHI D-Public 88.46 26 1301060000492969 LAL KUMARI JOSHI D-Public 221.15 27 1301060000658323 INDIRA -

754 17 - 23 April 2015 20 Pages Rs 50

#754 17 - 23 April 2015 20 pages Rs 50 DOR BAHADUR BISTA AVALANCHE MORE EQUITY Kesang Tseten’s ANNIVERSARY new documentary ON EVEREST investigates the BY OM ASTHA RAI disappearance of Nepal’s foremost 31 CHILDREN anthropologist 20 LOST THEIR IN MEMORY years ago FATHERS Surya Bahadur Thapa BY DAVID DURKAN (1928-2015) PAGE 16-17 PAGE 19 PAGE 7 SARA LEVINE clients to the top. of eight Nepali guides were busy Despite the attention to fixing ropes and ladders on a insurance and compensation, new, hopefully safer route up BACK TO WORK the disproportionate risk that the the Khumbu Icefall as heavy 300 high altitude workers face unseasonal snowfall engulfed s the mountaineering altitude workers, the Nepali while employed every year on Mt Everest this week (pic, above). community prepares to guides have gone back to what Everest has not diminished. The More than 300 climbers are Amark the first anniversary they have to do for a living – least-paid workers are still doing waiting at Base Camp for the of the Everest avalanche tragedy risking their lives to fix ropes, the most arduous and dangerous route to be ready and the weather last year which killed 16 high ladders and ferrying rich western work on the mountains. A team to clear. 2 EDITORIAL 17 - 23 APRIL 2015 #754 THE 2072 CONSTITUTION Even for their own self-interest and self-respect, top politicians would do well to end this farce ith the Nepali new year comes progress by being a federal, secular new hope that there may finally republic. -

Sagarmathako(English)… Final

Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editing Advisors Dr. Govinda Raj Bhattarai Rajeshwor Karki Proposer Dr. Laxman Prasad Gautam Editor Momila Translator & Language Editor Mahesh Paudyal Publisher Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan [Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation] (Under the project of Nepal Academy) Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editor : Momila Translator & Language Editor : Mahesh Paudyal Publisher : Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan (Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation) ©:Publisher Edition : First, 2011 Copies : 1001 Cover Design : Graphic Workshop Layout : Jeevan Nepal Printer : Modern Printing Press Kantipath, Kathmandu, Phone: 4253195 Price : NRs. 1,200.00 IRs. 1,000.00 US$ 25.00 Euro 20.00 ISBN: 978-9937-2-3657-7 DANCING SOUL OF MOUNT EVEREST (an anthology of selected modern Nepali poems) Editorial Context Heart-Transfer/Moksha Esteemed Readers! Here in editorial context, I extend words of gratitude that express themselves, though they might have remained apparently unexpressed. All of your accepted / unaccepted self-reflections shall become collages on the canvas of the history assimilated in this anthology. Dear Feelers! Wherever and whenever questions evolve, the existential consciousness of man keeps exploring the horizon of possibilities for the right answer even without the ultimate support to fall back upon. Existential revelations clearly dwell on the borderline, though it might be in a clash. In the present contexts, at places, questions of Nepali identity, modernity, representativeness, poetic quality, mainstream or periphery, temporal boundaries and limitations of number evolve – wanted or unwanted. Amidst the multitude of these questions, Dancing Soul of Mount Everest has assumed this accomplished form in its attempt to pervade the entirety as far as possible. -

Download Publication

RESEARCH REPORT Emerging Issues of Confict in November 2019 Federalized Context in Nepal 1 EMERGING ISSUES OF CONFLICT IN FEDERALIZED NEPAL Research Report November 2019 ASIAN ACADEMY FOR PEACE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT Emerging Issues of Conflict in Federalized Context in Nepal November 2019 1000 Copies ASIAN ACADEMY Copyright : © FOR PEACE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ISBN : 978-9937-0-6973-1 Research Advisors : Mr. Shiva K Dhungana Mr. Tulasi R Nepal Reacher Team : Leader – Rabindra Bhattarai Member – Rita Bhadra Shrestha Member – Sharad Chandra Neupane Publisher : Asian Academy for Peace, Research and Development Thapagaun, Baneshwor, Kathmandu Email: [email protected] Tel: 015244060 i FOREWORD The research ‘Emerging Issues of Conflict in Federalized Context in Nepal’ has aimed at identifying the issues related to the implementation of the federal restructuring in the country. The research is an outcome of the desk review and field level interviews and focus group discussions in nine districts namely Ilam, Jhapa, Morang, Dhanusha, Mahottari, Makawanpur, Surkhet, Kailali and Rukum West, as well as drawings from a national level interaction held in Kathmandu to disseminate and validate the findings from the field. Asian Academy for Peace, Research and Development (Asian Peace Academy) expresses its sincere gratitude to Kurve Wustrow, Centre for Training and Networking in Non-violence Actions and Civil Society Platform for Peacebuilding and Statebuilding (CSPPS) for their support to undertake this research. A team of researchers collected and analysed the information to draw findings of the study. Therefore, the research is a collaborative effort of the researchers and field level supporting hands. I would like to thank Mr. -

35Th Anniversary: ILO-Nepal Partnership

International Labour Organization P.O. Box: 8971, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: (+977 1) 528514, 542129, 545005, 531752 Fax: (+977 1) 531332, Email: [email protected] http://www.ilo.org/kathmandu Cover_Final 28th Nov.p65 2-3 1/31/2008, 4:42 PM 35th Anniversary: ILO-Nepal Partnership International Labour Office Copyright © International Labour Organization 2001 First published 2001 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the sources is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the ILO Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, Institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WIP 9HE (Fax: 44 171 436 3986), in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 (Fax: 1 508 750 4470) or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organizations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licenses issued to them for this purposes. ILO 35th Anniversary: ILO - Nepal Partnership Kathmandu, International Labour Office, 2001 ISBN: 92-2-112605-6 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office conceming the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

Clampdowns and Courage Ifj South Asia Press Freedom Report 2017-2018

CLAMPDOWNS AND COURAGE IFJ SOUTH ASIA PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2017-2018 SIXTEENTH ANNUAL SOUTH ASIA PRESS FREEDOM REPORT (2017-2018) 2 IFJ PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2017–2018 3 CONTENTS This document has been produced Cover Photo: Students and activists by the International Federation of holding ‘I am Gauri’ placards take part 1. FOREWORD 4 Journalists (IFJ) on behalf of the in a rally held in memory of journalist South Asia Media Solidarity Network Gauri Lankesh in Bangalore, India, (SAMSN). on September 12, 2017. The murder 2. OVERVIEW 6 Afghan Independent Journalists’ of Gauri Lankesh, a newspaper editor Association and outspoken critic of the ruling Hindu nationalist party sparked an Bangladesh Manobadhikar Sangbadik SPECIAL SECTIONS outpouring of anger and demands Forum for a thorough investigation. CREDIT: Federation of Nepali Journalists MANJUNATH KIRAN / AFP 3. IMPUNITY 10 Free Media Movement, Sri Lanka Indian Journalists’ Union This spread: Indian journalists take 4. RURAL JOURNALISTS 18 Journalists Association of Bhutan part in a protest on May 23, 2017 Media Development Forum Maldives after media personnel were injured 5. GENDER - #METOO AND 26 National Union of Journalists, India covering clashes in Kolkata between National Union of Journalists, Nepal police and demonstrators who were calling for pricing reforms in the THE MEDIA Nepal Press Union agriculture sector. CREDIT: DIBYANGSHU Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists SARKAR/AFP 6. INTERNET SHUTDOWNS 32 Sri Lanka Working Journalists’ Association South Asia Media Solidarity Network This document has been produced COUNTRY CHAPTERS (SAMSN) – Defending rights of with support from the United journalists and freedom of expression Nations Educational, Scientific and 7. -

Clampdowns and Courage South Asia Press Freedom Report 2017-2018

CLAMPDOWNS AND COURAGE SOUTH ASIA PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2017-2018 SIXTEENTH ANNUAL SOUTH ASIA PRESS FREEDOM REPORT (2017-2018) 2 IFJ PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2017–2018 3 CONTENTS This document has been produced Cover Photo: Students and activists by the International Federation of holding ‘I am Gauri’ placards take part 1. FOREWORD 4 Journalists (IFJ) on behalf of the in a rally held in memory of journalist South Asia Media Solidarity Network Gauri Lankesh in Bangalore, India, (SAMSN). on September 12, 2017. The murder 2. OVERVIEW 6 Afghan Independent Journalists’ of Gauri Lankesh, a newspaper editor Association and outspoken critic of the ruling Hindu nationalist party sparked an Bangladesh Manobadhikar Sangbadik SPECIAL SECTIONS outpouring of anger and demands Forum for a thorough investigation. CREDIT: Federation of Nepali Journalists MANJUNATH KIRAN / AFP 3. IMPUNITY 10 Free Media Movement, Sri Lanka Indian Journalists’ Union This spread: Indian journalists take 4. RURAL JOURNALISTS 18 Journalists Association of Bhutan part in a protest on May 23, 2017 Media Development Forum Maldives after media personnel were injured 5. GENDER - #METOO AND 26 National Union of Journalists, India covering clashes in Kolkata between National Union of Journalists, Nepal police and demonstrators who were calling for pricing reforms in the THE MEDIA Nepal Press Union agriculture sector. CREDIT: DIBYANGSHU Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists SARKAR/AFP 6. INTERNET SHUTDOWNS 32 Sri Lanka Working Journalists’ Association South Asia Media Solidarity Network This document has been produced COUNTRY CHAPTERS (SAMSN) – Defending rights of with support from the United journalists and freedom of expression Nations Educational, Scientific and 7. AFGHANISTAN 38 in South Asia. -

Srno Name BOID No Allotedkitta 1 KRISHNA BAHADUR THAPA

srno name BOID_no AllotedKitta 1 KRISHNA BAHADUR THAPA 1301010000000436 10 2 BHUWAN POKHAREL 1301010000000761 10 3 LAXMI PRASAD KHAKUREL 1301010000001313 10 4 RAMESHWOR PRADHAN 1301010000001497 10 5 PRAKASH SHRESTHA 1301010000002530 10 6 BARSHANA SHAKYA 1301010000002695 10 7 SHREE RAM KHANAL 1301010000003023 10 8 PADMA MANANDHAR 1301010000004390 10 9 SHREE KRISHNA THAPA 1301010000004430 10 10 SAFAL SHRESTHA 1301010000004766 10 11 MANOJ KUMAR KHANAL 1301010000005852 10 12 TANKA BAHADUR SHRESTHA 1301010000006860 10 13 RAMBHA DEVI SHRESTHA 1301010000007218 10 14 ISHWOR KARKI 1301010000007505 10 15 TIL BAHADUR KHADKA CHHETRI 1301010000008190 10 16 SHUBHAM DHUNGANA 1301010000008319 10 17 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 1301010000009308 10 18 HEM BAHADUR LIMBU 1301010000009443 10 19 SWECHCHHA DAHAL 1301010000009561 10 20 SHYAM KRISHNA DAHAL 1301010000009589 10 21 SARASWATI ADHIKARI 1301010000009857 10 22 RAJENDRA KUMAR RAUT 1301010000009920 10 23 PRAKASH SINGH KATHAYAT 1301010000009954 10 24 SUBAS POUDEL 1301010000019293 10 25 DURLAV NEPAL 1301010000019713 10 26 PURNA PRASAD BHETUWAL 1301010000020581 10 27 PUSHPA KATUWAL 1301010000021281 10 28 GOMA SHRESTHA 1301010000021361 10 29 PRAKASH ARYAL 1301010000010345 10 30 BUDDHA KRISHNA MANANDHAR 1301010000010419 10 31 UMA MANANDHAR 1301010000010423 10 32 PURNA BAHADUR SANGAT 1301010000011013 10 33 SHIVA SHRESTHA 1301010000013920 10 34 RAM MANI KHANAL 1301010000014242 10 35 HIRA THAPA MAGAR 1301010000014911 10 36 PRABINA BHANDARI 1301010000015191 10 37 SHOBHITA KALIKA 1301010000015311 10 38 SHAWANTI SHARMA 1301010000016176 -

From Vaccines to a Balancing Act, Deuba Faces Tough Foreign Policy Challenges It Is Not Just About India and China Anymore

WI THOUT F EAR O R F A V O U R Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXIX No. 156 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 37.0 C 16.2 C Saturday, July 24, 2021 | 09-04-2078 Dipayal Jumla From vaccines to a balancing act, Deuba faces tough foreign policy challenges It is not just about India and China anymore. With the changes in international rivalries, Nepal needs to tread carefully while safeguarding its interests, observers say. ANIL GIRI KATHMANDU, JULY 23 Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba has his plate full. And there are a cou- ple issues he needs to address immedi- ately—the sooner the better. Besides calibrating Nepal’s foreign policy, particularly vis-a-vis India and China, a perennial challenge for every government in Nepal given its geopolitical location, there is an added task for Deuba—securing Covid-19 vaccines. That the pandemic is trig- gering a huge geopolitical flux is something the 10-day-old prime minis- ter cannot ignore. Then there is clearing up the mess that his predecessor KP Sharma Oli POST FILE PHOTO created in Nepal’s handling of its for- Sher Bahadur Deuba AFP/RSS eign relations. An overview shows performers and athlete delegations taking part in the opening ceremony of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, at the Olympic “Obviously he faces some chal- While taking the vote of confidence Stadium in Tokyo on Friday. lenges in the changing regional on Sunday, Prime Minister Deuba and global scenarios in the gave some indications of his foreign post-Covid world,” said a policy when he said its priority will joint-secretary at the Ministry of begin with neighbouring countries Foreign Affairs. -

General Members

NEPAL LAW SOCIETY GENERAL MEMBERS Address S. N. Name Email 1. ANANDA MOHAN BHATTARAI (D R) Justice, Supreme Court [email protected] 2. AGNI KHAREL Senior Advocate, Attorney General, Nepal [email protected] 3. AMITA SAIJU SHRESTHA Senior Advocate, Supreme Court [email protected] 4. ANIL PRASAD KHANAL Advocate, Balkhu, Lalitpur [email protected] 5. ANIL KUMAR SINHA Justice, Supreme Court [email protected] Former Judge Appellate court, Former 6. ANITA MANANDHAR JOSHI [email protected] Executive Member, NBA Advocate, Supreme Court 7. ANJU KAYASTHA [email protected] Executive Member, NBA 8. ANJU UPRETI DHAKAL Judge, High Court [email protected] Chairperson, National Human Rights 9. ANUP RAJ SHARMA Commission, Former Chief Justice, [email protected] Supreme Court Joint Secretary, Ministry of Law and 10. ARJUN KUMAR KHADKA [email protected] Justice 11. ARJUN PRASAD LAMSAL Senior Advocate [email protected] 12. BABU RAM SHARMA BHATTRAI Advocate, Palpa [email protected] 13. BABURAM DAHAL Advocate, Kathmandu [email protected] 14. BABURAM REGMI Judge, High Court [email protected] Senior Advocate, Kathmandu Former 15. BADRI BAHADUR KARKI [email protected] Attorney General 16. BAIDYA NATH UPADHYAY Former Justice, Supreme Court [email protected] 17. BALKRISHNA NEUPANE Senior Advocate, Kathmandu [email protected] Senior Advocate, Kathmandu, Former 18. BASANTA RAM BHANDARY [email protected] Attorney General 19. BASUDEV JNAWALI Advocate, Banke [email protected] 20. BHARAT BAHADUR KARKI (DR) Former Justice, Supreme Court [email protected] 21. BHIMARJUN ACHARYA (D R) Advocate, Kathmandu [email protected] Advocate [email protected] 22. BIJAYA PRASAD MISHRA Former General Secretary, NBA 23.