Arxiv:Math/0609447V1 [Math.DG] 15 Sep 2006 Eerhfrti Ril a Upre Ytedgrsac U Research DFG the by Supported Was Faces”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Student Writing the Journal of Student Writing

2019 THe Journal of Student Writing THe Journal of Student Writing 2019 Supervising Editor Bradley Siebert Managing Editors Jennifer Pacioianu Ande Davis Consulting Editor Muffy Walter The Angle is produced with the support of the Washburn University English Department. All contributors must be students at Washburn University. Prizewinners in each category were awarded a monetary prize. Works published here remain the intellectual property of their creators. Further information and submission guidelines are available on our website at washburn.edu/angle. To contact the managing editors, email us at [email protected]. Table of Contents First Year Writing Tragedies Build Bridges Ethan Nelson . 3 Better Than I Deserve Gordon Smith . 7 The Power of Hope Whit Downing . 11 Arts and Humanities A Defense of the Unethical Status of Deceptive Placebo Use in Research Gabrielle Kentch . 15 Personality and Prejudice: Defining the MBTI types in Jane Austen’s novels Madysen Mooradian . 27 “Washburn—Thy Strength Revealed”: Washburn University and the 1966 Tornado Taylor Nickel . 37 Washburn Student Handbooks/Planners and How They’ve Changed Kayli Goodheart . 45 The Heart of a Musician Savannah Workman . 63 Formation of Identity in 1984 Molly Murphy . 67 Setting Roots in the Past Mikaela Cox. 77 Natural and Social Sciences The Effects of Conspiracy Exposure on Politically Cooperative Behavior Lydia Shontz, Katy Chase, and Tomohiro Ichikawa . 91 A New Major is Born: The Life of Computer Science at Washburn University Alex Montgomery . 111 Kinesiology Tape: Physiological or Psychological? Mikaela Cox . .121 Breaking w/the Fifth, an Introduction to Spherical Geometry Mary P. Greene . 129 Water Bears Sydney Watters . -

The Sphere by Itself: Can We Distribute Points on It Evenly?

Chapter III The sphere by itself: can we distribute points on it evenly? III.1. The metric of the sphere and spherical trigonometry As we shall see throughout this chapter, the geometry of the “ordinary sphere” S2 two dimensional in a space of three dimensions harbors many pitfalls. It’s much more subtle than we might think, given the nice roundness and all the sym- metries of the object. Its geometry is indeed not made easier at least for certain questions by its being round, compact, and bounded, in contrast to the Euclidean plane. Sect. III.3 will be the most representative in this regard; but, much simpler and more fundamental, we encounter the “impossible” problem of maps of Earth, which we will scarcely mention, except in Sect. III.3; see also 18.1 of [B]. One of the reasons for the difficulties the sphere poses is that its group of isometries is not at all commutative, whereas the Euclidean plane admits a commutative group of trans- lations. But this group of rotations about the origin of E3 the orthogonal group O.3/ is crucial for our lives. Here is the place to quote (Gromov, 1988b): “O.3/ pervades all the essential properties of the physical world. But we remain intellectually blind to this symmetry, even if we encounter it frequently and use it in everyday life, for instance when we experience or engender mechanical movements, such as walking. This is due in part to the non commutativity of O.3/,whichis difficult to grasp.” Since spherical geometry is not much treated in the various curricula, we permit ourselves at the outset some very elementary recollections, which are treated in detail in Chap. -

259 ) on the Equations of Loci Traced Upon the Surface of The

259 ) On the Equations of Loci traced upon the Surface of the Sphere, as expressed by Spherical Co-ordinates. By THOMAS STE- PHENS DAVIES, Esq. F.R.S.ED. F.R.A.S. (Read 16th January 1832J 1 HE modern system of analytical geometry of three dimensions originated with CLAIRAULT, and received its final form from the hands of MONGE. DESCARTES, it is true, had remarked, that the orthogonal projections of a curve anyhow situated in space, upon two given rectangular planes, determined the magnitude, species, and position of that curve; but this is, in fact, only an appro- priation to scientific purposes of a principle which must have been employed from the earliest period of architectural delinea- tion—the orthography and ichnographyyor the ground-plan and section of the system of represented lines. Had DESCARTES, however, done more than make the suggestion—had he pointed out the particular aspect under which it could have been ren- dered available to geometrical research—had he furnished a suit- able notation and methods of investigation—and, finally, had he given a few examples, calculated to render his analytical pro- cesses intelligible to other mathematicians;—then, indeed, this branch of science would have owed him deeper obligations than it can now be said to do. Still I do not wish to be understood to undervalue the labours of that extraordinary man, indirectly at least, upon this subject; for it is certain, that, though he did succeed in placing the inquiry in its true position, yet it is ulti- mately to his method of treating plane loci, by means of indeter- minate algebraical equations, that we owe every thing we know in 260 Mr DAVIES on the Equations of Loci the Geometry of Three Dimensions, beyond its simplest elements, as well as the most interesting and important portions of the doc- trine of plane loci itself. -

Analytic Methods for Simulated Light Transport

ANALYTIC METHODS FOR SIMULATED LIGHT TRANSPORT James Richard Arvo Yale University This thesis presents new mathematical and computational to ols for the simula tion of light transp ort in realistic image synthesis New algorithms are presented for exact computation of direct il lumination eects related to light emission shadow ing and rstorder scattering from surfaces New theoretical results are presented for the analysis of global il lumination algorithms which account for all interreec tions of light among surfaces of an environment First a closedform expression is derived for the irradiance Jacobian which is the derivative of a vector eld representing radiant energy ux The expression holds for diuse p olygonal scenes and correctly accounts for shadowing or partial o cclusion Three applications of the irradiance Jacobian are demonstrated lo cat ing lo cal irradiance extrema direct computation of isolux contours and surface mesh generation Next the concept of irradiance is generalized to tensors of arbitrary order A recurrence relation for irradiance tensors is derived that extends a widely used formula published by Lamb ert in Several formulas with applications in com puter graphics are derived from this recurrence relation and are indep endently veried using a new Monte Carlo metho d for sampling spherical triangles The formulas extend the range of nondiuse eects that can be computed in closed form to include illumination from directional area light sources and reections from and transmissions through glossy surfaces Finally new analysis -

Augmenting SAND with a Spherical Data Model∗ (EXTENDED ABSTRACT)

In Proc. of Intl. Conf. on Discrete Global Grids, Santa Barbara, CA, March 2000. Augmenting SAND with a Spherical Data Model∗ (EXTENDED ABSTRACT) Houman Alborzi and Hanan Samet Department of Computer Science Center for Automation Research Institute for Advanced Computer Studies University of Maryland College Park, MD 20740 {houman,hjs}@cs.umd.edu November 30, 2014 Abstract SAND is a spatial database and information browser system developed at University of Maryland which supports 2D and 3D data models. The experi- ence in extending SAND to include a spherical data model thereby enabling SAND to perform spatial queries on spherical data and to browse their re- sults in an incremental manner is described. The focus is on the issues that arise in adding a spherical data model to a database that has been built on the basis of the planar data model. Special emphasis is placed on how the data structure was chosen for the task. The various geometrical primitives that were needed for modeling spherical data as well as the algorithms that were required in the implementation are also described. As SAND is based on the quadtree representation, a natural method for adding spherical data to SAND was to find a spherical adaptation of the quadtree. The sphere was mapped into a quadtree representation by projecting the sphere onto a cube, and then constructing the quadtree on the faces of cube. Alternatively, it is also pos- sible to map the sphere into a plane, and then simply use a planar quadtree. Some of the differences between these approaches are discussed. -

Lobachevski Illuminated: Content, Methods, and Context of the Theory of Parallels

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2007 Lobachevski Illuminated: Content, Methods, and Context of the Theory of Parallels Seth Braver The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Braver, Seth, "Lobachevski Illuminated: Content, Methods, and Context of the Theory of Parallels" (2007). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 631. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/631 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOBACHEVSKI ILLUMINATED: CONTENT, METHODS, AND CONTEXT OF THE THEORY OF PARALLELS By Seth Philip Braver B.A., San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California, 1999 M.A., University of California at Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, California, 2001 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematical Sciences The University of Montana Missoula, MT Spring 2007 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School Dr. Gregory St. George, Committee Co-Chair Department of Mathematical Sciences Dr. Karel Stroethoff, Committee Co-Chair Department of Mathematical Sciences Dr. James Hirstein Department of Mathematical Sciences Dr. Jed Mihalisin Department of Mathematical Sciences Dr. James Sears Department of Geology Braver, Seth, Ph.D., May 2007 Mathematical Sciences Lobachevski Illuminated: The Content, Methods, and Context of The Theory of Parallels. -

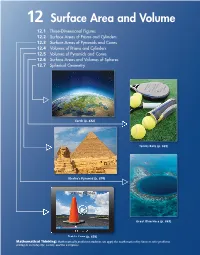

12 Surface Area and Volume

12 Surface Area and Volume 12.1 Three-Dimensional Figures 12.2 Surface Areas of Prisms and Cylinders 12.3 Surface Areas of Pyramids and Cones 12.4 Volumes of Prisms and Cylinders 12.5 Volumes of Pyramids and Cones 12.6 Surface Areas and Volumes of Spheres 12.7 Spherical Geometry EarthEarth (p.(p 692) TeTennisnnis BallsBalls (p(p.. 68685)5) KhKhafre'sf 'P Pyramid id ((p. 674)674) SEE the Big Idea GrGreateat BlBlueue HHoleole (p(p.. 66669)9) TTrTrafficafffic CCoConene ((p(p.. 65656)6) Mathematical Thinking: Mathematically proficient students can apply the mathematics they know to solve problems arising in everyday life, society, and the workplace. MMaintainingaintaining MathematicalMathematical ProficiencyProficiency Finding the Area of a Circle (7.9.B) Example 1 Find the area of the circle. A = πr2 Formula for area of a circle 8 in. = π ⋅ 82 Substitute 8 for r. = 64π Simplify. ≈ 201.06 Use a calculator. The area is about 201.06 square inches. Find the area of the circle. 1. 2. 3. 20 cm 6 m 9 ft Finding the Area of a Composite Figure (7.9.C) Example 2 Find the area of the composite figure. 17 ft The composite figure is made up of a rectangle, a triangle, and a semicircle. 16 ft Find the area of each figure. 32 ft 30 ft Area of rectangle Area of triangle Area of semicircle 1 πr2 A =ℓw A = — bh A = — 2 2 1 π(17)2 = 32(16) = — (30)(16) = — 2 2 = 512 = 240 ≈ 453.96 So, the area is about 512 + 240 + 453.96 = 1205.96 square feet. -

Šesterokut 3.4Em Solutions

ŠESTEROKUT SOLUTIONS 2 0 2 1 SADRŽAJ I Fizika 3 Dimenzionalna analiza i “slobodan” pad 4 Couple of ideas about one dimensional gases 7 One dimensional gas.................................... 7 Tools from statistical physics............................... 8 Mass of stars......................................... 9 Galileo 11 II Matematika 13 Automati 14 Matriˇcneavanture 16 Spherical geometry 22 Motivation.......................................... 22 Problems of Physical Nature................................ 22 Axioms............................................ 25 Purely Mathematical results................................ 27 Part I Fizika DIMENZIONALNA ANALIZA I “SLOBODAN” PAD At times, to reach a valid physical law, one can use a tool called dimensional analysis. An example of the use of this tool is presented on free fall. When a sphere of mass m and radius r is dropped into free fall from height h, it re- quires a certain amount of time to reach the ground. The total falling time can depend on the values of the parameters describing the body and the forces present in the sys- tem. Supposing there is no air drag and no buoyancy, the only parameter describing the forces on the sphere is the gravitational acceleration g. Thus, we can try to write the falling time as: t = Amahbggrd , where a, ..., d are unknown coefficients and A is some constant. • Determine the possible combinations of values of a, ..., d. S. (2 points) Since the left side of the equation has the dimension of time, thr right side exponents are restricted: m [s] = [1][kg]a[m]b[ ]g[m]d s2 immediately giving a = 0 and g = −1/2 and hence b + d = 1/2. • Perform a virtual experiment using a simulation tool available at shorturl.at/mKRY4. -

LECTURE NOTES in GEOMETRY Géza Csima, Ákos G.Horváth BUTE

LECTURE NOTES IN GEOMETRY Géza Csima, Ákos G.Horváth BUTE 2019 Contents 1 Absolute geometry 4 1.1 Axiom system . 4 1.1.1 Incidence . 4 1.1.2 Order . 5 1.1.3 Congruence . 6 1.1.4 Continuity . 7 1.1.5 Parallels . 7 1.2 Absolute theorems . 8 1.3 Orthogonality . 11 2 Hyperbolic geometry 14 2.1 Parallel lines on the hyperbolic plane . 14 2.1.1 Perpendicular transverse of ultraparallel lines . 15 2.2 Line pencils and cycles . 16 2.3 Models of the hyperbolic geometry . 17 2.3.1 Orthogonality in the Cayley-Klein model . 17 2.3.2 Stereographic projection . 18 2.3.3 Inversion . 20 2.4 Distance and angle of space elements . 21 2.4.1 Mutual position of space elements (E3) . 21 2.4.2 Mutual position of space elements (H3) . 21 2.4.3 Perpendicular transverse of non-intersecting hyperbolic space elements 22 2.4.4 Cross-ratio . 23 2.4.5 Distances in the hyperbolic space . 23 2.4.6 Angle and distance in the Cayley-Klein model . 24 2.4.7 Hyperboloid model . 24 2.4.8 Pole-polar relation . 25 2.5 Models of the Euclidean plane . 26 2.6 Area on the hyperbolic plane . 27 2 3 Classification of isometries 29 3.1 Isometries of the Euclidean plane . 29 3.2 Isometries of the Euclidean space . 32 4 Analytic geometry 35 4.1 Vectors in the Euclidean space . 35 4.2 Transformation of E3 with one fix point (origin) . 37 4.3 Spherical geometry . 40 4.3.1 Spherical Order axioms . -

Geometries and Transformations

Geometries and Transformations Euclidean and other geometries are distinguished by the transformations that preserve their essential properties. Using linear algebra and trans- formation groups, this book provides a readable exposition of how these classical geometries are both differentiated and connected. Following Cayley and Klein, the book builds on projective and inversive geometry to construct “linear” and “circular” geometries, including classical real metric spaces like Euclidean, hyperbolic, elliptic, and spherical, as well as their unitary counterparts. The first part of the book deals with the foundations and general properties of the various kinds of geometries. The latter part studies discrete-geometric structures and their symme- tries in various spaces. Written for graduate students, the book includes numerous exercises and covers both classical results and new research in the field. An understanding of analytic geometry, linear algebra, and elementary group theory is assumed. Norman W. Johnson was Professor Emeritus of Mathematics at Wheaton College, Massachusetts. Johnson authored and coauthored numerous journal articles on geometry and algebra, and his 1966 paper ‘Convey Polyhedra with Regular Faces’ enumerated what have come to be called the Johnson solids. He was a frequent participant in international con- ferences and a member of the American Mathematical Society and the Mathematical Association of America. Norman Johnson: An Appreciation by Thomas Banchoff Norman Johnson passed away on July 13, 2017, just a few months short of the scheduled appearance of his magnum opus, Geometries and Trans- formations. It was just over fifty years ago in 1966 that his most famous publication appeared in the Canadian Journal of Mathematics: “Convex Polyhedra with Regular Faces,” presenting the complete list of ninety-two examples of what are now universally known as Johnson Solids. -

Geometric Issues in Spatial Indexing

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: GEOMETRIC ISSUES IN SPATIAL INDEXING Houman Alborzi, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Dissertation directed by: Professor Hanan Samet Department of Computer Science We address a number of geometric issues in spatial indexes. One area of interest is spherical data. Two main examples are the locations of stars in the sky and geodesic data. The first part of this dissertation addresses some of the challenges in handling spherical data with a spatial database. We show that a practical approach for integrating spherical data in a conventional spatial database is to use a suitable mapping from the unit sphere to a rectangle. This allows us to easily use conventional two-dimensional spatial data struc- tures on spherical data. We further describe algorithms for handling spherical data. In the second part of the dissertation, we introduce the areal projection, a novel projection which is computationally efficient and has low distortion. We show that the areal projec- tion can be utilized for developing an efficient method for low distortion quantization of unit normal vectors. This is helpful for compact storage of spherical data and has applica- tions in computer graphics. We introduce the QuickArealHex algorithm, a fast algorithm for quantization of surface normal vectors with very low distortion. The third part of the dissertation deals with a CPU time analysis of TGS, an R-tree bulkloading algorithm. And finally, the fourth part of the dissertation analyzes the BV-tree, a data structure for storing multi-dimensional data on secondary storage. Contrary to the popular belief, we show that the BV-tree is only applicable to binary space partitioning of the underlying data space. -

5Th Postulate, 129 Addition of Vectors, 132 Additivity of Dot Product, 114

Index 5th postulate, 129 base of prism, 30 base of pyramid, 31 addition of vectors, 132 base of spherical frustum, 91 additivity of dot product, 114 base of spherical sector, 96 altitude of cone, 77 base of spherical segment, 91 altitude of cylinder, 76 bases of frustum, 32 altitude of frustum, 32 bilateral symmetry, 61 altitude of prism, 30 bilinearity, 137 altitude of pyramid, 31 box, 31 altitude of spherical segment, 91 angle between line and plane, 21 Cartesian coordinate system, 141 angle between lines, 20 Cartesian projection, 20 angle between planes, 18 Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, 138 angle between skew lines, 20 Cavalieri’s principle, 45 angle on hyperbolic plane, 150 center, 88 antiprism, 72, 74 center of homothety, 52 apothem, 32 center of mass, 119 Archimedean solids, 72 center of symmetry, 59 Archimedes’ axiom, 131 central symmetry, 59 area, 152 Ceva’s theorem, 122 area of sphere, 93 circle, 161 area of spherical frustum, 93 circumscribed prism, 77 area of spherical segment, 93 circumscribed pyramid, 78 associative, 109 circumscribed sphere, 103 associativity, 111, 120 collinear, 123 axial cross section, 86 common notion, 128 axiom, 128, 132 commutative, 109 axiom of completeness, 131 composition, 138, 154 axiom of dimension, 134 concurrent, 37 axioms of order, 130 cone, 77 axis of revolution, 75 congruent dihedral angles, 17 axis of symmetry, 61 congruent figures, 129, 138 conical frustum, 78 ball, 88 conical surface, 77 barycenter, 119 consistency, 144 base of cone, 77 convex polyhedral angle, 23 base of conical frustum, 78