19 a Review on the Structure and Mechanical Properties of Mollusk Shells – Perspectives on Synthetic Biomimetic Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Downloaded From

Document downloaded from: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/52433 This paper must be cited as: Fombuena Borrás, V.; Benardi, L.; Fenollar Gimeno, OÁ.; Boronat Vitoria, T.; Balart Gimeno, RA. (2014). Characterization of green composites from biobased epoxy matrices and bio-fillers derived from seashell wastes. Materials and Design. 57:168-174. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2013.12.032. The final publication is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2013.12.032 Copyright Elsevier Characterization of green composites from biobased epoxy matrices and bio-fillers derived from seashell wastes V. Fombuena*1, L. Bernardi2, O. Fenollar1, T. Boronat1, R.Balart1 1 Instituto de Tecnología de Materiales (ITM) Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) Plaza Ferrandiz y Carbonell 1, 03801, Alcoy (Alicante), Spain 2 Centro de Tecnologia (CT) Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM) Santa Maria - RS, 97105-900, Brasil *Corresponding author: Vicent Fombuena Telephone number/fax: 96 652 84 33 Email: [email protected] Characterization of green composites from biobased epoxy matrices and bio-fillers derived from seashell wastes V. Fombuena*, L. Bernardi2, O. Fenollar1, T. Boronat1, R.Balart1 1 Instituto de Tecnología de Materiales (ITM) Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) Plaza Ferrandiz y Carbonell 1, 03801, Alcoy (Alicante), Spain 2 Centro de Tecnologia (CT) Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM) Santa Maria - RS, 97105-900, Brasil Abstract The seashells, a serious environmental hazard, are composed mainly by calcium carbonate, which can be used as filler in polymer matrix. The main objective of this work is the use of calcium carbonate from seashells as a bio-filler in combination with eco-friendly epoxy matrices thus leading to high renewable contents materials. -

Brief Glossary and Bibliography of Mollusks

A Brief Glossary of Molluscan Terms Compiled by Bruce Neville Bivalve. A member of the second most speciose class of Mollusca, generally bearing a shell of two valves, left and right, and lacking a radula. Commonly called clams, mussels, oysters, scallops, cockles, shipworms, etc. Formerly called pelecypods (class Pelecypoda). Cephalopoda. The third dominant class of Mollusca, generally without a true shell, though various internal hard structures may be present, highly specialized anatomically for mobility. Commonly called octopuses, squids, cuttles, nautiluses. Columella. The axis, real or imaginary, around and along which a gastropod shell grows. Dextral. Right-handed, with the aperture on the right when the spire is at the top. Most gastropods are dextral. Gastropod. A member of the largest class of Mollusca, often bearing a shell of one valve and an operculum. Commonly called snails, slugs, limpets, conchs, whelks, sea hares, nudibranchs, etc. Mantle. The organ that secretes the shell. Mollusk (or mollusc). A member of the second largest phylum of animals, generally with a non-segmented body divided into head, foot, and visceral regions; often bearing a shell secreted by a mantle; and having a radula. Operculum. A horny or calcareous pad that partially or completely closes the aperture of some gastropodsl. Periostracum. The proteinaceous layer covering the exterior of some mollusk shells. Protoconch. The larval shell of the veliger, often remains as the tip of the adult shell. Also called prodissoconch in bivlavles. Radula. A ribbon of teeth, unique to mollusks, used to procure food. Sinistral. Left-handed, with the aperture on the left when the spire is at the top. -

Biotribology Recent Progresses and Future Perspectives

HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Biosurface and Biotribology ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]] www.elsevier.com/locate/bsbt Biotribology: Recent progresses and future perspectives Z.R. Zhoua,n, Z.M. Jinb,c aSchool of Mechanical Engineering, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China bSchool of Mechanical Engineering, Xian Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China cSchool of Mechanical Engineering, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK Received 6 January 2015; received in revised form 3 March 2015; accepted 3 March 2015 Abstract Biotribology deals with all aspects of tribology concerned with biological systems. It is one of the most exciting and rapidly growing areas of tribology. It is recognised as one of the most important considerations in many biological systems as to the understanding of how our natural systems work as well as how diseases are developed and how medical interventions should be applied. Tribological studies associated with biological systems are reviewed in this paper. A brief history, classification as well as current focuses on biotribology research are analysed according to typical papers from selected journals and presentations from a number of important conferences in this area. Progress in joint tribology, skin tribology and oral tribology as well as other representative biological systems is presented. Some remarks are drawn and prospects are discussed. & 2015 Southwest Jiaotong University. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Keywords: Biotribology; Biosurface; Joint; Skin; Dental Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................2 2. Classifications and focuses of current research. ..........................................................3 3. Joint tribology .................................................................................4 3.1. -

Taroona Seashell Fauna

Activity – Exploring Seashell Fauna (Gr 3 - 10) Overview: Different types of marine invertebrate make different types of shells. Measure and draw a range of shells and try to identify them. Comparing the size, shape and colours of seashells is a great way of exploring the diversity in molluscs that live along rocky shorelines. Looking closely at shells can reveal the type of mollusc that created it, and may provide an indication of their way of life and diet. There is also an entire tiny world of micro-molluscs, 1 – 10 mm in size, in the drifts of shells that accumulate along the strandline or in the lee of intertidal rocks. For those willing to get down on hands and knees you will be amazed at what can be learned about the local environment from a single handful of shell grit. 1 – 10 mm sized micro-molluscs found in a handful of shell grit. Image: S. Grove. TASK: Split the class into small groups and collect a range of empty shells from along the foreshore. Make sure the shells are empty, as we don’t want to displace living creatures. Materials: magnifying glass ruler flat tray with black cardboard pencil paper eraser shell ID chart - Before you undertake the DEP Discovery Trail print out a few copies of this pictorial guide to help the kids identify shells commonly found in coastal environments. This material relates to shells found in Aboriginal middens of Victoria, but is also useful for intertidal studies. http://www.dpcd.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/35633/A_Guide_to_Shells_Augus t_2007.pdf 1. -

Experimental Study on Partial Replacement of Coarse Aggregate by Seashell & Partial Replacement of Cement by Flyash

International Journal of Latest Research in Engineering and Technology (IJLRET) ISSN: 2454-5031 www.ijlret.comǁ Volume 2 Issue 3ǁ March 2016 ǁ PP 69-76 EXPERIMENTAL STUDY ON PARTIAL REPLACEMENT OF COARSE AGGREGATE BY SEASHELL & PARTIAL REPLACEMENT OF CEMENT BY FLYASH R. Yamuna Bharathi1, S. Subhashini2, T. Manvitha3, S. Herald Lessly4 1, 2&3Undergraduate student, Department of Civil Engineering, R.M.K.Engineering College, TamilNadu, India. 4Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, R.M.K.Engineering College, TamilNadu, India. ABSTRACT:The growing concern of resource depletion and global pollution has lead to the development of new materials relying on renewable resources. Many by- products are used as aggregate for concrete. Seashell waste which is a major financial and operational burden on the shellfish industry is used as an ingredient in concrete thus offering alternatives to preserve natural coarse aggregate for future generation. Seashell is mainly composed of calcium and the rough texture make it suitable to be used as partial coarse aggregate replacement which provides an economic alternative to the conventional materials such as gravel. Experimental studies were performed on conventional concrete and mixtures of seashell with concrete. The percentage of seashell, is varied from 3% to 11%. Also the cement is replaced for 25% of flyash. The mechanical properties of concrete such as compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, and workability are evaluated. This research helps to access the behaviour of concrete mixed with seashell and determination of optimum percentage of combined mixture which can be recommended as suitable alternative construction material in low cost housing delivery especially in coastal areas and near fresh water where they are found as waste. -

Seashell Craft - Puri, Orissa Decorative Items by Prof

D’source 1 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Resource Seashell Craft - Puri, Orissa Decorative Items by Prof. Bibhudutta Baral, Divyadarshan C. S. and Ranjitha M. C. NID Campus, Bengaluru Source: http://www.dsource.in/resource/seashell-craft-pu- ri-orissa 1. Introduction 2. Tools and Raw Materials 3. Making Process 4. Products 5. Video 6. Contact Details D’source 2 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Resource Introduction Seashell Craft - Puri, Orissa Decorative Items Seashell is an exoskeleton of marine mollusks such as snails, clams, oysters, etc., which is a hard outer protective by layer. These seashells are formed in layers and are composed of calcium carbonate with a less quantity of protein Prof. Bibhudutta Baral, Divyadarshan C. S. and (not more than 2%). Seashells are normally found in beach drift, which is natural waste matter left along strand- Ranjitha M. C. lines on beaches by the waves and the tides. Some of these seashells such as oyster shells are used as soil condi- NID Campus, Bengaluru tioner in horticulture. Shells of Turbinella pyrum (the holy shanka) are reflected to be sacred to the god Vishnu. In olden days seashells like cowry shells and tusk shells were using as a currency in Arab and North Western North America for many centuries because of the durability and easy to carry. Cowries were habitually treated as genuine fertility charms. In some of the south Indian states these cowries are used to make astrological predic- tions. The moche civilization of ancient Peru worshipped the sea and depicted shells in their traditional art. -

Phd Thesis Summary

UNIVERSITY POLITEHNICA OF BUCHAREST Doctoral School Materials Science and Engineering 313 Splaiul Independenţei, District 6, Bucharest, 060042 Tel/fax: 021 402 9624; http://www.sdsim.upb.ro PhD Thesis Summary Contributions on the manufacturing of 3D constructs using biomimetic powders for biomedical applications PhD Candidate: Eng. Aura-Cătălina Mocanu PhD Supervisor: Prof. Florin Miculescu DOCTORAL COMMITTEE University President Prof.dr.habil.eng. Iulian Vasile Antoniac from Politehnica of Bucharest PhD University Prof.dr.habil.eng. Florin Miculescu from Supervisor Politehnica of Bucharest University Referee Prof.dr.habil.eng. Ioana Csaki from Politehnica of Bucharest Technical University Referee Prof.dr.eng. Cătălin Ovidiu Popa from of Cluj-Napoca University Referee Prof.dr.eng. Mircea Horia Țierean from Transilvania of Brașov Bucharest 2021 Contributions on the manufacturing of 3D constructs using biomimetic powders for biomedical applications Abstract The continuous advances recorded in the biomaterials science have led to a near- complete understanding of processes involved in osseointegration. In good congruence with this general direction, the main goal of the PhD thesis was (i) to refine a complex and reproducible synthesis technology for the manufacture of biomimetic calcium phosphate-based (CaP) ceramic materials (e.g., hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate phases, in different proportions) and (ii) to develop, implement and multi-parametrically assess the performance of innovative porous products derived from marble and seashell precursors as potential bone graft substitutes (to be applied in the restorative and reconstructive orthopaedic surgery). The technology refined and advanced in this PhD thesis lies at the basis of the development of three types of products, whose mechanical and preliminary in vitro performances were further engineered by the addition of selected reinforcing components and porogen agents, respectively. -

And Registration Tea/Coffee Welcome Address

Wednesday 4th November 09:00 Welcome and registration Tea/Coffee David Vaughan : 09:15 Welcome address Director of Science Session 1: Land 09:30 Jennifer Brown Seasonal penguin colony colour change at Signy, Antarctica 09:50 Elise Biersma First evidence of long-term persistence of mosses in Antarctica 10:10 Tun Jan Young Resolving flow and deformation of store glacier, west Greenland using FMCW radar 10:30 Tea/Coffee Session 2: Air 10:50 Ian White Dynamical response to the equatorial QBO in the northern winder extratropical stratosphere 11:20 Michelle McCrystall Modelling the influence of remote teleconnection on Arctic climate variability 11:40 Jenny Turton Spatial and temporal characteristics of foehn winds over the Larsen ice shelf 12:00 Hoi Ga Chan Modelling nitrogen oxide emission from snow 12:20 Lunch 13:30 Hayley Allison Tracey Dornan Irene Malmierca Zoe Roseby First year welcome Jesamine Bartlett Rebecca Frew Christine McKenna Felipe Lorenz Simoes David Buchanan Tom Hudson Emily Potter Rebecca Vignols Harriet Clewlow Amy King 13:45 David Vaughan Keynote talk 1: “Ice sheets, climate and sea-level” Session 3: Water: Circulation 14.15 Lewis Drysdale The seasonal distribution of freshwater from meteoric sources and sea ice melt in Svalbard fjords 14.35 Heather Regan Sources and fate of freshwater in the ocean west of the Antarctic Peninsula 14.55 Ewa Karczewska 3-D transport pathways from the southern ocean 15:15 Tea/Coffee 15.45 Ryan Patmore Making a gyre, the southern ocean way 16.05 Erik Mackie Has Antarctica ice loss altered the -

The Effect of Seashell Waste on Setting and Strength Properties of Class C Fly Ash Geopolymer Concrete Cured at Ambient Temperature

Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Vol. 14, No. 3 (2019) 1220 - 1230 © School of Engineering, Taylor’s University THE EFFECT OF SEASHELL WASTE ON SETTING AND STRENGTH PROPERTIES OF CLASS C FLY ASH GEOPOLYMER CONCRETE CURED AT AMBIENT TEMPERATURE ARIE WARDHONO* Civil Engineering Department, Universitas Negeri Surabaya, Kampus Unesa Ketintang, Surabaya 60231, Indonesia, *Email: [email protected] Abstract The main issue of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete is the need for heat curing treatment. The use of a material with a high calcium content is assumed to be able to resolve this problem. This paper reports the effect of seashell waste on setting time and strength properties of Class C fly ash geopolymer concrete cured at ambient temperature. Geopolymer concrete was prepared by using high calcium Class C fly ash activated by activator solution. A proportion of seashell waste was added with fly ash to accelerate the curing at ambient temperature instead of using heat curing. The setting time and strength properties were calculated by Vicat, slump, and compressive strength tests. The result shows that the highest compressive strength was achieved by geopolymer concrete with 10% seashell waste addition and exhibited a comparable strength to that normal concrete. The 10% seashell waste addition also increased the setting time, which affected the strength of geopolymer concrete. It can be suggested that the seashell waste inclusion with Class C fly ash improves the performance of geopolymer cured at ambient temperature. Keywords: Ambient temperature, Class C fly ash, Geopolymer concrete, Seashell waste, Setting time, Strength. 1220 The Effect of Seashell Waste on Setting and Strength Properties of . -

Biopolymer (Chitin) from Various Marine Seashell Wastes: Isolation and Characterization

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Central University Of Technology Free State - LibraryCUT, South Africa J Polym Environ (2018) 26:2207–2218 DOI 10.1007/s10924-017-1118-y ORIGINAL PAPER Biopolymer (Chitin) from Various Marine Seashell Wastes: Isolation and Characterization Ernestine Alabaraoye1 · Mathew Achilonu1 · Robert Hester1 Published online: 4 October 2017 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2017 Abstract Chitin has been produced from different sea Introduction waste sources including, molluscs (mussel and oyster shell), crustacean (prawn and crab) and fish scale (pang and silver Chitin and its main derivatives chitosan belong to the new scales) using deproteinization and demineralization as chem- families of biological macromolecules and their study are ical methods. The conditions of chemical extraction process becoming interesting to many researchers in the domain of determine the quality of chitin. The obtained results revealed study. Chitin, also known as identified as poly 2-acetamido- that, about 1 and 10% HCl and NaOH were adequate concen- 2-deoxy-β-D-glucose firstly was identified in 1884 as pure trations for deproteinization and demineralization process polysaccharides and are available in large amount organic respectively. Chitin from oyster and crab shell waste had the biopolymer material found in the physical world [1, 2]. highest yield of 69.65 and 60.00% while prawn, mussel shell, Chitin is located next to cellulose, according to the amount pang and silver scales had the lowest yield of 40.89, 35.03, produced annually by biosynthesis. This biopolymer shows 35.07 and 31.11% respectively. -

Seashellweb.Pdf

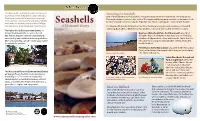

Nature Series The Monmouth County Park System has two envi- Searching for Seashells ronmental centers dedicated to nature education. One of the best times to fi nd seashells along the Jersey Shore is in late winter and early spring. Each has a trained staff of naturalists to answer The rough winter surf and storms such as Nor’easters will bring more seashells to the beach. Look visitor questions and a variety of displays, exhibits, for these natural treasures along the high tide line mixed in among the seaweed and fl otsam. and hands-on activities where visitors of all ages Seashells can learn about area wildlife and natural history. of Monmouth County The Monmouth County Park System has three locations to enjoy beach combing and seashell collecting. Each off ers a diff erent variety of shells to discover due to their diff erent locations. The Huber Woods Environmental Center, on Brown’s Dock Road in the Locust Section of Bayshore Waterfront Park, Port Monmouth is located Middletown, features newly renovated exhibits along the shore of Sandy Hook Bay. Here you will fi nd large about birds, plants, wildlife and the Lenape Indians. numbers of slipper shells, clams and mussels. This is also the Miles of surrounding trails off er many opportunities best spot for locating the State Seashell of New Jersey, the to enjoy and view nature knobbed whelk. Fisherman’s Cove, Manasquan is located on the Manasquan River just inside the Manasquan Inlet. Here you can fi nd mus- Bayshore Waterfront Park sels, clams and oysters. Seven Presidents Oceanfront Park, Long Branch off ers the bounty of the Atlantic Ocean. -

Biomimetic Calcium Phosphates Derived from Marine and Land Bioresources

Chapter 6 Biomimetic Calcium Phosphates Derived from Marine and Land Bioresources Florin Miculescu, Aura-Cătălina Mocanu, FlorinAndreea Maidaniuc, Miculescu, Aura-Cătălina Cătălina-Andreea Dascălu, Mocanu, AndreeaMarian Miculescu, Maidaniuc, Ștefan Cătălina-Andreea Ioan Voicu and Dascălu, MarianRobert-Cătălin Ciocoiu Miculescu, Ștefan Ioan Voicu and Robert-Cătălin Ciocoiu Additional information is available at the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.71489 Abstract This chapter aims to establish the key factors for technological optimization of biogenic calcium phosphate synthesis from marine and land resources. Three natural calcium sources—marble, seashell and bovine bone—were considered as raw materials. The pro- posed materials are suitable candidates for the synthesis of bone substitutes similar to the inorganic bone component. The synthesis processes were developed based on the investi- gations of thermal phenomena (TGA-DSC analysis) that can occur during thermal treat- ments. By this method, we were able to determine the optimum routes and temperatures for the complete dissociation of calcium carbonate as well as risk-free deproteinization of bovine bone. An exhaustive characterization, performed with modern and comple- mentary techniques such as morphology (SEM), composition (EDS, XRF) and structure (FT-IR, XRD), is presented for each precursor. The final chemical composition of ceramic products can be modulated through a careful control of the key parameters involved in the conversion, in order to create long-term performant biphasic apatite biomaterials, with broad medical applicability. Identifying the suitable strategies for this modulation contributes to an appreciable advance in orthopedic tissue engineering.