A Study of Ideas in Oklahoma a Dissertation Submit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 1909) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1909 Volume 27, Number 08 (August 1909) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 27, Number 08 (August 1909)." , (1909). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/550 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUGUST 1QCQ ETVDE Forau Price 15cents\\ i nVF.BS nf//3>1.50 Per Year lore Presser, Publisher Philadelphia. Pennsylvania THE EDITOR’S COLUMN A PRIMER OF FACTS ABOUT MUSIC 10 OUR READERS Questions and Answers on the Elements THE SCOPE OF “THE ETUDE.” New Publications ot Music By M. G. EVANS s that a Thackeray makes Warrington say to Pen- 1 than a primer; dennis, in describing a great London news¬ _____ _ encyclopaedia. A MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE THREE MONTH SUMMER SUBSCRIP¬ paper: “There she is—the great engine—she Church and Home Four-Hand MisceUany Chronology of Musical History the subject matter being presented not alpha¬ Price, 25 Cent, betically but progressively, beginning with MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. -

Untitled, It Is Impossible to Know

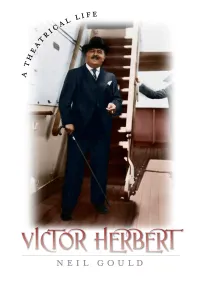

VICTOR HERBERT ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE i ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE ii VICTOR HERBERT A Theatrical Life C:>A<DJA9 C:>A<DJA9 ;DG9=6BJC>K:GH>INEG:HH New York ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2008 Neil Gould All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gould, Neil, 1943– Victor Herbert : a theatrical life / Neil Gould.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2871-3 (cloth) 1. Herbert, Victor, 1859–1924. 2. Composers—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML410.H52G68 2008 780.92—dc22 [B] 2008003059 Printed in the United States of America First edition Quotation from H. L. Mencken reprinted by permission of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, Maryland, in accordance with the terms of Mr. Mencken’s bequest. Quotations from ‘‘Yesterthoughts,’’ the reminiscences of Frederick Stahlberg, by kind permission of the Trustees of Yale University. Quotations from Victor Herbert—Lee and J.J. Shubert correspondence, courtesy of Shubert Archive, N.Y. ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iv ‘‘Crazy’’ John Baldwin, Teacher, Mentor, Friend Herbert P. Jacoby, Esq., Almus pater ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE v ................ -

Senate Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 144 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 9, 1998 No. 141 Senate (Legislative day of Friday, October 2, 1998) The Senate met at 9:30 a.m., on the RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY nificant bill that is important to every expiration of the recess, and was called LEADER State in the Nation. It had been tied up to order by the President pro tempore The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The with various and sundry problems, but (Mr. THURMOND). able majority leader is recognized. with a lot of hard work and a lot of co- Mr. LOTT. Thank you, Mr. President, operation, that bill was cleared. We and good morning to you. hope, now, the House will take expedi- PRAYER f tious action and we can complete ac- tion on the water resources bill before The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John SCHEDULE we go out for the year. Also, we did the Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: Mr. LOTT. Mr. President, this morn- human resources reauthorization and Eternal God, sovereign of history, ing there will be 15 minutes remaining the vocational education bill. When who gives beginnings and ends to the for debate on the religious freedom you couple higher education and voca- phases of our work, on whom our mor- bill. At 9:45, under a previous order, the tional education, plus the Coverdell A+ tal efforts depend, soon this hallowed Senate will proceed to vote on the pas- bill that Congress passed, there has Chamber will be silent for a time. -

A ADVENTURE C COMEDY Z CRIME O DOCUMENTARY D DRAMA E

MOVIES A TO Z SEPTEMBER 2020 D 10 to 11 (2009) 9/16 D Blackboard Jungle (1955) 9/30 D Countdown (1968) 9/19 a y 3:10 to Yuma (1957) 9/19 u Blackmail (1939) 9/19 ADVENTURE h Creature from The Black Lagoon (1954) 9/26 u The 39 Steps (1935) 9/1 c Blithe Spirit (1945) 9/22 R Crossing Delancey (1988) 9/6 c Blondie Goes to College (1942) 9/9 c COMEDY w Cry Havoc (1944) 9/10 P –––––––––––––––––––––– A ––––––––––––––––––––––– y Blood on the Moon (1948) 9/10 D A Cry in the Dark (1988) 9/21 o ABBA - the Movie (1977) 9/4 D Blossoms in the Dust (1941) 9/29 z CRIME u Cry Terror (1958) 9/9 sD The Ace of Hearts (1921) 9/13 h The Body Snatcher (1945) 9/10 o Cuba Feliz (2000) 9/7 a The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1939) 9/23 a Bomba and the Jungle Girl (1952) 9/26 o DOCUMENTARY u The Curse of the Cat People (1944) 9/10 sm The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) 9/9 z Born to Kill (1947) 9/10 a African Treasure (1952) 9/19 a The Boy and the Pirates (1960) 9/16 –––––––––––––––––––––– D ––––––––––––––––––––––– D DRAMA c Ah, Wilderness (1935) 9/23 c Boy Meets Girl (1938) 9/11 u Danger Signal (1945) 9/12, 9/13 Hc Air-Tight (1931) 9/14 D Boys Town (1938) 9/23 m Dangerous When Wet (1953) 9/20 e EPIC R All That Heaven Allows (1955) 9/24 R Brief Encounter (1945) 9/22 D Daredevil Drivers (1938) 9/12 D All That Jazz (1979) 9/2 D Bright Road (1953) 9/13 S R Dark Victory (1939) 9/18 P HORROR/SCIENCE-FICTION D All the King’s Men (1949) 9/20 c Bud Abbott and Lou Costello in Hollywood D Daughters of the Dust (1991) 9/22 Ho Alluring Alaska (1941) 9/19 (1945) 9/11 y Death -

THE SPONSOR This Page Intentionally Left Blank the SPONSOR NOTES on a MODERN POTENTATE

THE SPONSOR This page intentionally left blank THE SPONSOR NOTES ON A MODERN POTENTATE Erik Barnouw OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford New York Toronto Melbourne Oxford University Press Oxford London Glasgow New York Toronto Melbourne Wellington Nairobi Dares Salaam Cape Town Kuala Lumpur Singapore Jakarta Hong Kong Tokyo Delhi Bombay Calcutta Madras Karachi Copyright © 1978 by Erik Barnouw First published by Oxford University Press, New York, 1978 First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 1979 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Barnouw, Erik, 1908- The sponsor. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Television advertising—United States. 2. Tele- vision programs—United States. 3. Television broad- casting—Social aspects—United States. I. Title. HF6146.T42B35 301.16'1 76-51708 ISBN 0-19-502311-0 ISBN 0-19-502614-4 pbk. 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 Printed in the United States of America To D.B. This page intentionally left blank ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author is grateful for the opportunity he had to study, as a 1976 Fellow of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., the role and influence of the sponsor in American television. He was free to pursue his inquiry wherever it led him. The resulting docu- ment is his responsibility. He also owes a deep debt of gratitude to the many people in television—and surrounding territory—who helped and encour- aged him in this exploration. October 1911 E. B. New York, N.Y. This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS H PART ONE RISE 7 1 On the Eve of the Sponsor 9 2 The First 400 10 3 New System 14 4 Monopoly Games 20 5 National 21 6 The Dispossessed 27 7 Uprising 28 8 Two Worlds 32 9 Senator Truman 3 7 10 Transition 41 11 Qualms 48 12 Changing the Guard 5 5 13 Going Public 58 14 Demographics 68 15 Do You Agree or Disagree . -

Happy Thanksgividg from the Times Staff Nov

Serving Our Loyal Readers ^ince 1875 -cnz.^u fN ‘wywd Aynasw "3AW i s y i d o o s 911 3.Hand Mddd Adnastf 9 u o '' t VOL. CXVIV NO. 47 TOWNSHIP OF NEPTUNE, N.J. THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 24, 1994 USPS 402420 THIRTY-FIVE CENTS What's A 90th Birthday Gala Happening? Thursday THANKSGIVING NOV. 24 Frl.*Sun. FAMOUS TRAINS HOLIDAY SHOW DEC. 2,3,4 607 8th Ave., Asbury Park Fri 7:30-9:30 pm, Sat-Sun 12-5 Friday DEC. 2 Auditorium Square, Ocean Grove 6:30 PM Sahirday DEC. 3 Avon 3to7 PM SaUirday DEC* 3 Sunday DEC. 4 Avon Fri.«8atv “VICTORIAN EVPHiMW^Poetry) DEC.S&10 Sahirday CHRISTMAS ROUSE TOUR . DEC. 10 Ocean Grove Annual Sapphire Ball Top - Dr. Roy Mittman (center) sells a few raffle tickets to Chris Korow (left) and Mrs. .lune Lynch (right) Associate Direc tor of .lersey Shore Medical Center Right - .John Lloyd (center) CEO & President of Jersey Shore Medical Center stands with his wife Maureen (left) and Karen Thompson (right) who co-chaired the Decoration Committee for the bail. Neptune - More than 1970, raised funds for Jersey after dinner. This was fol mo, co-chairs, reser- 600 of the best-dressed Shore’s medical equipment lowed by a generous dona vations/seating; Maureen people in town attended fund. The $350-per-couple tion of $30,000 presented by Lloyd, Sea Girt, and Karen Jersey Shore Medical Cen Ball employed and exciting the Department of Dentistry. Thompson, Ocean, co ter’s Twenty-fourth Annual silent auction and a raffle-for- Musical highlights of the chairs, decorations; Toni Sapphire Ball on Saturday, cash drawing to stimulate evening included a concert Seda Morales, West End, November 19, 1994, at the shd V featuring Ronnie Spec- Is Pleased donations. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 150 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2004 No. 130 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Tuesday, November 16, 2004, at 2 p.m Senate MONDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2004 The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME called to order by the President pro LEADER The PRESIDENT pro tempore. Under tempore [Mr. STEVENS]. The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The the previous order, leadership time is majority leader is recognized. reserved. PRAYER The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- f f fered the following prayer: SCHEDULE AMERICAN JOBS CREATION ACT Let us pray. Mr. FRIST. Mr. President, a good Co- OF 2004—CONFERENCE REPORT Majestic and Holy God, we give You lumbus Day to everyone. The PRESIDENT pro tempore. Under honor and praise. We thank You for the We reconvene today for what I expect the previous order, the Senate will re- spiritual awareness that prompted to be the final day of business before sume consideration of the conference statements about Sabbath rest in this adjournment. report to accompany H.R. 4520, which Chamber yesterday. Thank You also Yesterday, we invoked cloture on the the clerk will report. for the love of the sacred that led Sen- conference report to accompany the The assistant legislative clerk read ators and staff to participate in a FSC or JOBS bill. -

FREE to CHOOSE: a Personal Statement James M

Copyright © 1980, 1979 by Milton Friedman and Rose D. Friedman All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to: Permissions, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. 757 Third Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10017 The author wishes to thank the following publishers for per- mission to quote from the sources listed: Harvard Educational Review. Excerpts from "Alternative Pub- lic School Systems" by Kenneth B. Clark in the Harvard Edu- cational Review, Winter 1968. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. Newsweek Magazine. Excerpt from "Barking Cats " by Milton Friedman in Newsweek Magazine, February 19, 1973. Copy- right © 1973 by Newsweek, Inc. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission. The Wall Street Journal. Excerpts from "The Swedish Tax Revolt" by Melvyn B. Krauss in The Wall Street Journal, February 1, 1979. Reprinted by permission of The Wall Street Journal, © Dow Jones & Co., Inc., 1979. All rights reserved. Set in Linotype Times Roman Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Friedman, Milton, 1912– Free to choose. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Capitalism. 2. Welfare state. 3. Industry and state. I. Friedman, Rose D., joint author. II. Title. HB501.F72 330.12'2 79-1821 ISBN 0-15-133481-1 L M Other Books by Milton Friedman PRICE THEORY THERE IS NO SUCH THING AS A FREE LUNCH AN ECONOMIST'S PROTEST THE OPTIMUM QUANTITY OF MONEY AND OTHER ESSAYS DOLLARS AND DEFICITS A MONETARY HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES (with Anna J.