Local Cross-Border Cooperation Faces the Challenge of Sustainability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Legacy Lives On...” South East Fermanagh Foundation (SEFF) South East Fermanagh Foundation (SEFF)

THE PLEASE FILL OUT THE GREY AREA AND CLICK THE SEND BUTTON BELOW PLEASE ASK A THIRD paRty TO THOROUghly CHECK THISFACTOR DOCUY MENT - REPRINTS COST MONEY - Thank YOU CUSTOMER CONTACT THE FACTORY ORDER NO ITEM OF ORDER PRooF NO DATE NO OF PAGES IN THIS DOCUMENT THE PRODUCT EXTENT SIZE QUANTIT Y COloURS FACTORY MATERIAL CoVER MATERIAL INSIDE FINISHING DESIGNER EMAIL TELEPHONE NOTE PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE BOX PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE BOX PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE BOX Job can go to print AMEND & Job needs minor change AMEND & Job needs changes and PROCEED without changes PROCEED and can go to print then REPROOF new proof is required PLEASE LIST AMENDMENTS PLEasE AppRECiatE: If an order is placed which involves us producing Artwork or Proofs, and is then cancelled, there will be a charge for the time spent producing the same. PRintED FOR PURChasE ORDER NO (if applicable) (please see note below) If a P/O No. is required, it must be supplied before we will proceed with print run CUstOMER NamE DatE nOTE: Please allow 5 working days from confirmation of order. An express service is available which will incur an extra cost. Customers are assured the best efforts are made in executing the instruction given in connection with the work entrusted to us, however we do not accept responsibility for any error or inaccuracy which is not noted at this stage. Customers are therefore urged to thoroughly check and examine this document prior to authorising print runs. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Please refer to clause 12B of our (ACOS NI LTD T/A The Print Factory) standard terms and conditions on your (the Buyer)responsibility regarding the use of copyrighted material, copies of which are available on request. -

A Revised List of the Executive Assets in County Fermanagh Is Provided and an Update Will Be Provided to the Assembly Library

Conor Murphy MLA Minister of Finance Clare House, 303 Airport Road West Belfast BT3 9ED Mr Seán Lynch MLA Northern Ireland Assembly Parliament Buildings Stormont AQW: 6772/16-21 Mr Seán Lynch MLA has asked: To ask the Minister of Finance for a list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh. ANSWER A revised list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh is provided and an update will be provided to the Assembly Library. Signed: Conor Murphy MLA Date: 3rd September 2020 AQW 6772/16-21 Revised response DfI Department or Nature of Asset Other Comments Owned/ ALB Address (Building or (eg NIA or area of Name of Asset Leased Land ) land) 10 Coa Road, Moneynoe DfI DVA Test Centre Building Owned Glebe, Enniskillen 62 Lackaghboy Road, DfI Lackaghboy Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen 53 Loughshore Road, DfI Silverhill Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen Toneywall, Derrylin Road, DfI Toneywall Land/Depot (Surplus) Building Owned Enniskillen DfI Kesh Depot Manoo Road, Kesh Building/Land Owned 49 Lettermoney Road, DfI Ballinamallard Building Owned Riversdale Enniskillen DfI Brookeborough Depot 1 Killarty Road, Brookeborough Building Owned Area approx 788 DfI Accreted Foreshore of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares Area approx 15,100 DfI Bed and Soil of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares. Foreshore of Lough Erne – that is Area estimated at DfI Land Owned leased to third parties 95 hectares. 53 Lettermoney Road, Net internal Area DfI Rivers Offices and DfI Ballinamallard Owned 1,685m2 Riversdale Stores Fermanagh BT9453 Lettermoney 2NA Road, DfI Rivers -

1926 Census County Fermanagh Report

GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1926 COUNTY OF FERMANAGH. Printed and presented pursuant to the provisions of 15 and 16 Geo. V., ch. 21 BELFAST: PUBLISHED BY H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND. To be purchased directly from H. M. Stationery Office at the following addresses: 15 DONEGALL SQUARE WEST, BELFAST: 120 GEORGE ST., EDINBURGH ; YORK ST., MANCHESTER ; 1 ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF ; AD ASTRAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONDON, W.C.2; OR THROUGH ANY BOOKSELLER. 1928 Price 5s. Od. net THE. QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY OF BELFAST. iii. PREFACE. This volume has been prepared in accordance with the prov1s1ons of Section 6 (1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland), 1925. The 1926 Census statistics which it contains were compiled from the returns made as at midnight of the 18-19th April, 1926 : they supersede those in the Preliminary Report published in August, 1926, and may be regarded as final. The Census· publications will consist of:-· 1. SEVEN CouNTY VoLUMES, each similar in design and scope to the present publication. 2. A GENERAL REPORT relating to Northern Ireland as a whole, covering in more detail the. statistics shown in the County Volumes, and containing in addition tables showing (i.) the occupational distribution of persons engaged in each of 51 groups of industries; (ii.) the distribution of the foreign born population by nationality, age, marital condition, and occupation; (iii.) the distribution of families of dependent children under 16 · years of age, by age, sex, marital condition, and occupation of parent; (iv.) the occupational distribution of persons suffering frominfirmities. -

Sliabh Beagh Way

Sliabh Beagh Way Steeped in local myth and legend, the Sliabh Beagh Way meanders through the valleys of Co Tyrone, the drumlins of Co Monaghan and the lakelands of Co Fermanagh AUGHER F B1 B 07 8 3 TEMPO FIVEMILETOWN Fardross Forest Crocknagrally Forest 0 14 4 B 5 A 3 5 B Mullaghfad Forest Grogey Forest Jenkin Forest BROOKBOROUGH A 4 Knocks MAGUIRESBRIDGE Forest 5 4 1 3 5 A Carnmore B Forest Doon Forest LISNASKEA 6 Tully R Forest 187 B 1 4 3 Key to Map SECTION 1 - AUGHNACLOY TO ST PATRICK'S CHAIR AND WELL (12km) SECTION 2 - ST PATRICK'S WELL AND CHAIR TO BRAGAN (8.7km) SECTION 3 - BRAGAN TO MUCKLE ROCKS (8.8km) SECTION 4 - MUCKLE ROCKS TO ESHYWULLIGAN (9.6km) SECTION 5 - ESHYWULLIGAN TO TULLY FOREST (12.2km) Views of Lough Aportan SECTION 6 - TULLY FOREST TO LISNASKEA (14km) 02 | walkni.com Welcome to the AUGHNACLOY A A Sliabh Beagh Way 5 28 Favour Royal This 65km two-day walking route Forest follows a mixture of country lanes AUGHNACLOY and forest tracks as it explores the LISNASKEA varied countryside around South Fermanagh. A remote path across the expanse of moor around Sliabh Beagh is one of the highlights, while good signage and generally firm terrain make it suitable for all fit walkers. N 2 5 8 1 B 6 8 1 Lough Nadarra R Contents N12 04 - Section 1 MONAGHAN Aughnacloy to St Patrick's Chair and Well N2 N54 06 - Section 2 St Patrick's Well and Chair Route is described in a clockwise direction. -

PO Minister's Letter

AQW 6772/16-21 Annex A DfI Department or Nature of Asset Other Comments Owned/ ALB Address (Building or (eg NIA or area of Name of Asset Leased Land ) land) 10 Coa Road, Moneynoe DfI DVA Test Centre Building Owned Glebe, Enniskillen 62 Lackaghboy Road, DfI Lackaghboy Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen 53 Loughshore Road, DfI Silverhill Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen Toneywall, Derrylin Road, DfI Toneywall Land/Depot (Surplus) Building Owned Enniskillen DfI Kesh Depot Manoo Road, Kesh Building/Land Owned 49 Lettermoney Road, DfI Ballinamallard Building Owned Riversdale Enniskillen DfI Brookeborough Depot 1 Killarty Road, Brookeborough Building Owned Area approx 788 DfI Accreted Foreshore of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares Area approx 15,100 DfI Bed and Soil of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares. Foreshore of Lough Erne – that is Area estimated at DfI Land Owned leased to third parties 95 hectares. 53 Lettermoney Road, Net internal Area DfI Rivers Offices and DfI Ballinamallard Owned 1,685m2 Riversdale Stores Fermanagh BT9453 Lettermoney 2NA Road, DfI Rivers DfI Ballinamallard Yard Owned 4,200m2 Riversdale Fermanagh BT94 2NA Land area 0.89 DfI Portora Sluice Enniskillen Sluice Gates Owned hectacres Rosscrennagh to Rossharbour, DfI Land Owned 0.1236 Hectares Leggs - Railway Land Rosscrennagh to Rossharbour, 0.1302 0.1833 DfI Land Owned Leggs - Railway Land Hectares Drumard/Drumhoney, Kesh - DfI Land Owned 0.6150 Hectares Railway Land Drummoyagh/Drumhoney, Kesh - DfI Land Owned 0.6385 Hectares Railway Land Drummoyagh/Drumhoney, Kesh -

200 Years of Worship at St. Mark's, Aghadrumsee

Member of the worldwide Anglican Communion May 2019 £1.50/€1.65 200 YEARS OF WORSHIP AT ST. MARK’S, AGHADRUMSEE Also Inside,,, Bishop announces Diocesan appointments - Pages 64 & 65 Check out our website www.clogher.anglican.org ARMSTRONG Funeral Directors & Memorials Grave Plot Services • A dignified and personal 24hr service • Offering a caring and professional service Specialists In Quality Grave Care • Memorials supplied and erected • Large selection of headstones, vases open books • Cleaning of Headstones & Surrounds • Resetting Fallen or Leaning Headstones or Damaged Surrounds • Open books & chipping’s • Reconstruction of Sunken or Raised Graves • Also cleaning and renovations • Supply & Erection of Memorial Headstones & Grave Surrounds to existing memorials • Additional Inscriptions & Repairs to Lettering • Additional lettering • New Marble or Granite Chips in your Chosen Colour • Marble or Granite Chips Washed & Restored • Regular Maintenance Visits eg : Weekly, Monthly, or Special Dates Dromore Tel. • Floral Tributes(Anniversary or Special Dates) 028 8289 8424 Contractors to The Commonwealth Omagh Tel. 028 8224 0803 War Graves Commission Robert Mob. 077 9870 0793 A Quality Professional & Personal Service Derek Mob. www.graveimage.co.uk • [email protected] 079 0027 8633 Contact : Stuart Brooker Tel: 028 6634 1611 Mob: 07968 738 491 35 Kildrum Rd, Dromore, Cullen, Monea, Enniskillen BT93 7BR Co. Tyrone, BT78 3AS EMMA McADOO MCFHP MAFHP MNRRI Chiropody Treatments - General & Diabetic Footcare Attending Ballybay Pharmacy every 2nd Thursday • Home Clinic & Visiting Practice • Custom Made Orthotics Mobile: 086 1901247 Killygraggy, Aghabog, Co. Monaghan IAN MCELROY JOINERY For all your joinery, carpentry, roofing and tiling needs Tel: 02866385226 or 07811397429 Wrought Iron Gates, Railings & Victorian Style Outdoor Lighting Kenneth Hall 43 Abbey Road Lisnaskea Co. -

Constituency Profile Fermanagh and South Tyrone – June 2016

Constituency Profile Fermanagh and South Tyrone – June 2016 Constituency Profile – Fermanagh and South Tyrone June 2016 About this Report Welcome to the June 2016 Constituency Profile for Fermanagh and South Tyrone. This profile has been produced by the Northern Ireland Assembly’s Research and Information Service (RaISe) to support the work of Members. The report includes a demographic profile of Fermanagh and South Tyrone and indicators of Health, Education, Employment, Business, Low Income, Crime and Traffic and Travel. For each indicator, this profile presents: . The most up-to-date information available for Fermanagh and South Tyrone; . How Fermanagh and South Tyrone compares with the Northern Ireland average; and . How Fermanagh and South Tyrone compares with the other 17 Constituencies in Northern Ireland. For a number of indicators, ward level data1 is provided demonstrating similarities and differences within the constituency. A summary table has been provided showing the latest available data for each indicator, as well as previous data, illustrating change over time. Constituency Profiles are also available for each of the other 17 Constituencies in Northern Ireland and can be accessed via the Northern Ireland Assembly website. http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/assembly-business/research-and-information-service-raise/ The data used to produce this report has been obtained from the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency’s Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service (NINIS). To access the full range of information available on NINIS, please visit: http://www.ninis2.nisra.gov.uk/ Please note that the figures contained in this report may not be comparable with those in previous Constituency Profiles as figures are sometimes revised and as more up-to-date mid-year estimates are published. -

Andy Galloway Interview Transcript Amended

dc Diversity Challenges ‘A project supported by PEACE III Programme managed for the Special EU Programmes Body by the Community Relations Council/Pobal Consortium’. Green & Blue Project Andy Galloway Interview 14/10/13 I joined the Royal Ulster Constabulary in August 1981, and my first station was Rosslea, in Fermanagh, in south east Fermanagh. Prior to being allocated that station I didn’t even know where Rosslea was, I’m a county Antrim man, so I knew very little of the geography of Fermanagh at that time. I arrived out to this place in the south east corner of Fermanagh and found myself in a station that was literally a mile and a half from the border with county Monaghan, and I found myself very quickly listening to Garda on a daily basis, because in those days in our police stations and in our police cars we had a thing called the x-ray radio set. The x-ray radios were aerial to aerial radios and they had very short range. They were ideal for the RUC and the Garda to communicate with each other, the radios were not recorded, so they were quite often used for ordering fish and chips or cigarettes or all sorts of other things. But it allowed us to have conversations with our colleagues directly across the border and primarily they were used for vehicle checks, because the Garda would put their vehicles across to us, and we would put ours across to them, so we could check vehicles on our own systems. And that was my first introduction really with interaction with An Garda Síochána. -

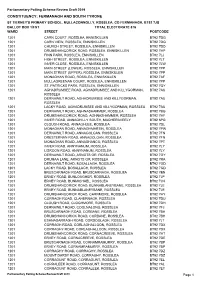

Constituency: Fermanagh and South Tyrone

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: FERMANAGH AND SOUTH TYRONE ST TIERNEY'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, MULLACONNOLLY, ROSSLEA, CO FERMANAGH, BT92 7JS BALLOT BOX 1/FST TOTAL ELECTORATE 876 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1201 CARN COURT, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7DG 1201 CARN VIEW, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7DG 1201 CHURCH STREET, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7DD 1201 DRUMSHANCORICK ROAD, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7HP 1201 FINN PARK, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7LJ 1201 HIGH STREET, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7LT 1201 INVER CLOSE, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7LW 1201 MAIN STREET (LOWER), ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7PP 1201 MAIN STREET (UPPER), ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7PP 1201 MONAGHAN ROAD, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7AF 1201 MULLAGREENAN COURT, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7PP 1201 ST. PATRICKS PARK, ROSSLEA, ENNISKILLEN BT92 7QY 1201 AGHADRUMSEE ROAD, AGHADRUMSEE AND KILLYGORMAN, BT92 7AU ROSSLEA 1201 DERNAWILT ROAD, AGHADRUMSEE AND KILLYGORMAN, BT92 7AU ROSSLEA 1201 LACKY ROAD, AGHADRUMSEE AND KILLYGORMAN, ROSSLEA BT92 7AU 1201 DERNAWILT ROAD, AGHNASHAMMER, ROSSLEA BT92 7BG 1201 DRUMSHANCORICK ROAD, AGHNASHAMMER, ROSSLEA BT92 7HF 1201 INVER ROAD, ANNAGHILLY SOUTH, MAGHERAVEELY BT92 6PG 1201 CLOUGH ROAD, ANNAGHLEE, ROSSLEA BT92 7DL 1201 MONAGHAN ROAD, ANNAGHMARTIN, ROSSLEA BT92 7PW 1201 DERNAWILT ROAD, ANNAGOLGAN, ROSSLEA BT92 7FN 1201 DRESTERNAN ROAD, ANNAGOLGAN, ROSSLEA BT92 7FN 1201 MONAGHAN ROAD, ANNASHANCO, ROSSLEA BT92 7PT 1201 INVER ROAD, ANNYNANUM, ROSSLEA BT92 7LY 1201 LISROON ROAD, ANNYNANUM, ROSSLEA BT92 7LY 1201 DERNAWILT ROAD, -

Tony Lenihan

Logainmneacha na mbailte fearainn i bparóistí Bhéal Leice, Theampall Cearna agus Dhroim Caorthainn i mbarúntacht Loirg Contae Fhear Manach: bunfhoirmeacha agus bríonna Tony Lenihan Tráchtas do chéim M.Litt. Roinn na Nua-Ghaeilge Ollscoil Mhá Nuad Ollscoil na hÉireann Má Nuad Ceann na Roinne: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn Stiúrthóir: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn Meán Fómhair 2016 Clár an Ábhair Focal Admhála .............................................................................................................................. 1 Achoimre ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Noda Ginearálta ............................................................................................................................ 4 Noda (Foinsí) ................................................................................................................................ 5 Plé ar na Foinsí.............................................................................................................................. 9 Caibidil 1 Cur síos ar an gceantar .............................................................................................. 12 Na Paróistí Dlí......................................................................................................................... 12 Léarscáil 1. Béal Leice, Teampall Carna agus Droim Caorthainn. ................................... 12 Geografaíocht na hÁite .......................................................................................................... -

Your Legacy Lives On... Cy Lives On

The Queen’s Award for Voluntary Service SOUTH EAST FERMANAGH FOUNDATION (SEFF) | SEFF’s Memorial Quilt | “Your Legacy lives on...” SOUTH EAST FERMANAGH FOUNDATION (SEFF) SOUTH EAST FERMANAGH FOUNDATION (SEFF) |FOREWORD | t is an immense honour for me I to be writing the Foreword for a describes how the innocent victims Project which strikes to the very heart of and survivors of terrorism and ‘other SEFF’s purpose as an organisation. Troubles related violence’ view those SEFF exists to support the innocent Legacy Lives On’ is a statement which victims and survivors of terrorism and ‘other Troubles related violence’ in means that even though people have ensuring that their individual needs been murdered and are no longer with are addressed and appropriate us that their contribution to building a interventions in the form of services are better community will not be forgotten provided. nor will their memory be extinguished. They will continue to be cherished and In recent years the organisation has loved. sought to progress a number of Projects which provide opportunities for those The associated book seeks to murdered to be remembered and for their families to be acknowledged for reader a sense of the human person the traumatic events that they have behind the name on the individual endured. SEFF’s Book and DVD Projects ‘I’ll I am no expert in sewing or embroidery Never Forget’ and ‘For God and Ulster’ - the vow of those who reject is a marvellous piece of work which very violence (each Project captures over much illustrates the love and respect 60 individual victim and survivor for which those depicted were and are Fermanagh, West Fermanagh, and held. -

Your Essential Guide to Walking in the Fermanagh and Omagh District Additional Information

Fermanagh & Omagh Walking Guide Your essential guide to walking in the Fermanagh and Omagh District Additional Information The walks have been graded into three categories: Easy Short walks generally fairly level going on well surfaced routes Moderate Longer walks with some gradients and generally on well surfaced routes Difficult Longer walks only suitable for more experienced walkers correctly equipped with waterproof clothing and strong walking boots Leave No Trace In order to minimise your social and environmental impacts on the outdoors, please follow the Seven Principles of Leave No Trace: 1. Plan Ahead and Prepare 2. Be Considerate of Others 3. Respect Farm Animals and Wildlife 4. Travel and Camp on Durable Ground 5. Leave What You Find 6. Dispose of Waste Properly 7. Minimise the Effects of Fire Plan ahead and prepare Maps in this guide are for illustrative purposes only. For those moderate and difficult walks it is advised that you obtain detailed maps before walking. Please ensure you are correctly equipped with suitable clothing and foot wear. Some of these walks are in truly natural surroundings, including steep ground, rocky scree, uneven surfaces and boggy sections – you are responsible for your own safety. Disclaimer Every care has been taken to ensure accuracy in the compilation of this guide. The information provided is, to the best of the promoter’s knowledge correct at the time of going to print. The promoters cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions but if they are brought to their notice, future publications will be amended accordingly. All maps are Crown Copyright and are reproduced with the permission of Land & Property Services under delegated authority from the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright and database right 2016 CS&LA156.