The Island Asylum in Scorsese's Shutter Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schizophrenia on the Main Character of the Shutter Island Film Based on Sigmund Freud’S Psychoanalysis Theory

SCHIZOPHRENIA ON THE MAIN CHARACTER OF THE SHUTTER ISLAND FILM BASED ON SIGMUND FREUD’S PSYCHOANALYSIS THEORY A Thesis Submitted to Letters and Humanities Faculty In Partial to Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Strata One By: GOFUR NIM: 208026000004 ENGLISH LETTER DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND HUMANITIES UIN SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2015 ABSTRACT Gofur, Schizophrenia on The Main Character of The Shutter Island Film Based on Sigmund Freud’s Psychoanalysis Theory. A Thesis Of Department of English Literature, Faculty of Adab and Humanities, Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State University, Jakarta, 2015. The purpose of this research is aimed to know schizophrenia on the main character of the Shutter Island film using psychoanalysis approach. The writer uses a qualitative desc riptive method in this research in which the data is collected from the script and watching film. Then, the writer analyzes them by using Psychoanalysis theory of Sigmund Freud. From the analysis, the writer finds that the main character has a personality problem because of regression to the primary narcissism and becomes schizophrenia as his defense. The main character regresses to the primary narcissism because of he is not comfortable of his psychosexual stages normally. The main character has bad experience during his childhood. Particularly, schizophrenia is linked to an early part of the oral stage called primary narcissism during which the ego has not separated from the id. The main character shows two symptoms of schizophrenia such as delusion and hallucination. Finally, he lives in his fictional story and keeps in his insanity when at the end of the healing method almost success. -

THESIS By: Fadly Sholehudin Abdhillah Mutaqin NIM 13320114 DEPARTMENT of ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY of HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS IS

A STUDY OF FILM ADAPTATION IN DENNIS LEHANE’S SHUTTER ISLAND (2003) THESIS By: Fadly Sholehudin Abdhillah Mutaqin NIM 13320114 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2020 i A STUDY OF FILM ADAPTATION IN DENNIS LEHANE’S SHUTTER ISLAND (2003) THESIS Presented to Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S.) By: Fadly Sholehudin Abdhillah Mutaqin NIM 13320114 Advisor: Agung Wiranata Kusuma, M.A. NIP 198402072015031004 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2020 ii STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP I state that the thesis entitled “A Study of Film Adaptation in Dennis Lehane’s Shutter Island (2003)” is my original work. I do not include any materials previously written or published by another person, except those ones that are cited as references and written in the bibliography. Hereby, if there is an objection or claim, I am the only person who is responsible for that. Malang, 04 Maret 2020 The researcher Materai 6000 Fadly Sholehudin A.M. 13320114 iii APPROVAL SHEET This to certify that Fadly Sholehudin Abdhillah Mutaqin’s thesis entitled A Study of Film Adaptation in Dennis Lehane’s Shutter Island (2003) has been approved for thesis examination at the Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang, as one of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S.). Malang, 05 March 2020 Approved by: Head of Department of Advisor English Literature Agung Wiranata Kusuma, M.A. -

Scapegoats and Redemption on Shutter Island Cari Myers University of Denver, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha Journal of Religion & Film Volume 16 Article 2 Issue 1 April 2012 5-25-2012 Scapegoats and Redemption on Shutter Island Cari Myers University of Denver, [email protected] Recommended Citation Myers, Cari (2012) "Scapegoats and Redemption on Shutter Island," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 16 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol16/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scapegoats and Redemption on Shutter Island Abstract The themes of redemptive violence, scapegoating, and ritual in the films of Martin Scorsese have provided much grist for critical scholarship. While it is going too far to claim that Scorsese is intentionally interpreting Girardian themes (which are themselves borrowed from a rich mythological tradition), the comparisons between the theorist and the director are compelling. My goal here is to establish the primary themes of scapegoating, mimesis, the cycle of violence, and feuding identities that occur in both Girard’s works and Scorsese’s films and pull them forward into a more recent work of Scorsese, Shutter Island. Keywords Violence, Scapegoating, Ritual, Girard Author Notes Cari Myers received a BA in English Literature from Pepperdine University, an MA in Youth and Family Ministry from Abilene Christian University, and an MTS from Brite Divinity at Texas Christian University. -

The Remake of Memory: Martin Scorsese's Shutter Island and Pedro Almodovar's the Skin I Live

Vera Dika THE REMAKE OF MEMORY: MARTIN SCORSESe’S SHUTTER ISLAND AND PEDRO Almodovar’S THE The history of cinema has given us objectification of consciousness (2012), SKIN I notable representations of states of or with more contemporary theorist memory, delusion, hallucination, and Laura Mulvey (1975) who interpreted dream. Cinematic states of conscious- the whole of narrative cinema as the ness arise in early German Expression- objectification of male sexual desire, LIVE IN* ist and Surrealist films, such as in The especially in relationship to the repre- Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Cabinet sentation of women. But in our current des Dr. Caligari, Robert Wiene, 1920) cinematic era, one that arguably be- and Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel, gins in the mid-1960s, or early 1970s, 1929). In Hollywood films there are and termed “postmodern” by the critic famous dream sequences, such as in Fredric Jameson (1983), a new form Spellbound (Alfred Hitchock, 1945), of “memory” begins to interject itself or re-creations of dream-like worlds, into the picture, or shall we say, into such as in the classic film noir, Laura the movie. That is, the viewer’s own (Otto Preminger, 1944), or renditions movie memories, not personal ones, of mad obsession, as in Frankenstein mind you, but cultural memories, ones (James Whale, 1931) or Dr. Jekyll and cued by cinematic elements strategi- Mr. Hyde (Rouben Mamoulian, 1931). cally re-created and recombined by the And in the US avant-garde film, works filmmakers. According to Jameson, this such as Maya Deren’s Meshes of the practice conflates past, present, and fu- Afternoon (1943), and Stan Brakhage’s ture, and puts our very understanding Anticipation of the Night (1958), cre- of history into jeopardy. -

American Independent Cinema 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

AMERICAN INDEPENDENT CINEMA 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Geoff King | 9780253218261 | | | | | American Independent Cinema 1st edition PDF Book About this product. Hollywood was producing these three different classes of feature films by means of three different types of producers. The Suburbs. Skip to main content. Further information: Sundance Institute. In , the same year that United Artists, bought out by MGM, ceased to exist as a venue for independent filmmakers, Sterling Van Wagenen left the film festival to help found the Sundance Institute with Robert Redford. While the kinds of films produced by Poverty Row studios only grew in popularity, they would eventually become increasingly available both from major production companies and from independent producers who no longer needed to rely on a studio's ability to package and release their work. Yannis Tzioumakis. Seeing Lynch as a fellow studio convert, George Lucas , a fan of Eraserhead and now the darling of the studios, offered Lynch the opportunity to direct his next Star Wars sequel, Return of the Jedi Rick marked it as to-read Jan 05, This change would further widen the divide between commercial and non-commercial films. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Until his so-called "retirement" as a director in he continued to produce films even after this date he would produce up to seven movies a year, matching and often exceeding the five-per-year schedule that the executives at United Artists had once thought impossible. Very few of these filmmakers ever independently financed or independently released a film of their own, or ever worked on an independently financed production during the height of the generation's influence. -

Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood

FRAMING FEMININITY AS INSANITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF MENTAL ILLNESS IN WOMEN IN POST-CLASSICAL HOLLYWOOD Kelly Kretschmar, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Harry M. Benshoff, Major Professor Sandra Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Debra Mollen, Committee Member Ben Levin, Program Coordinator Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kretschmar, Kelly, Framing Femininity as Insanity: Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood. Master of Arts (Radio, Television, and Film), May 2007, 94 pp., references, 69 titles. From the socially conservative 1950s to the permissive 1970s, this project explores the ways in which insanity in women has been linked to their femininity and the expression or repression of their sexuality. An analysis of films from Hollywood’s post-classical period (The Three Faces of Eve (1957), Lizzie (1957), Lilith (1964), Repulsion (1965), Images (1972) and 3 Women (1977)) demonstrates the societal tendency to label a woman’s behavior as mad when it does not fit within the patriarchal mold of how a woman should behave. In addition to discussing the social changes and diagnostic trends in the mental health profession that define “appropriate” female behavior, each chapter also traces how the decline of the studio system and rise of the individual filmmaker impacted the films’ ideologies with regard to mental illness and femininity. Copyright 2007 by Kelly Kretschmar ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................ 5 Women and Mental Illness in Classical Hollywood ............................... -

Not for Publication United States Court of Appeals

FILED NOT FOR PUBLICATION OCT 30 2013 MOLLY C. DWYER, CLERK UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS U.S. COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT WARNER BROS ENTERTAINMENT, No. 13-55352 INC., a Delaware corporation; et al., D.C. No. 2:12-cv-09547-PSG-CW Plaintiffs - Appellees, v. MEMORANDUM* THE GLOBAL ASYLUM, INC., a California corporation, DBA The Asylum, Defendant - Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Philip S. Gutierrez, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted October 7, 2013 Pasadena, California Before: FERNANDEZ, PAEZ, and HURWITZ, Circuit Judges. Defendant The Global Asylum, Inc. (“Asylum”) appeals the district court’s order granting Plaintiffs Warner Brothers Entertainment, Inc., New Line Productions, Inc., Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc., Saul Zaentz Company, and * This disposition is not appropriate for publication and is not precedent except as provided by 9th Cir. R. 36-3. New Line Cinema, LLC’s (collectively “Studios”) motion for a preliminary injunction. 1. “A plaintiff seeking a preliminary injunction must establish that he is likely to succeed on the merits, that he is likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief, that the balance of equities tips in his favor, and that an injunction is in the public interest.” Winter v. Natural Res. Def. Council, Inc., 555 U.S. 7, 20 (2008). The district court found that all four Winter elements were met. 2. On appeal, Asylum challenges only the district court’s ruling that the Studios are likely to succeed on their trademark infringement claim under 15 U.S.C. -

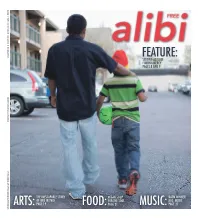

Arts: Food: Feature

FEATURE: VOLUME 28 | ISSUE 15 | APRIL 11-17, 2019 | FREE 2019 | ISSUE 15 APRIL 11-17, 28 VOLUME SEEKING ASYLUM FINDING MERCY PAGES 8 AND 9 PHOTO BY ERIC WILLIAMS BY PHOTO THE INESCAPABLE STORY VEGAN SOUP BoBM WINNER OF ONE IN TWO FOR THE SOUL M.O. MUSIC ARTS: PAGE 19 FOOD: PAGE 21 MUSIC: PAGE 27 STIRRING THE MELTING POT SINCE 1992 SINCE 1992 POT THE MELTING STIRRING [ 2] WEEKLY ALIBI APRIL 11-17, 2019 APRIL 11-17, 2019 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] alibi VOLUME 28 | ISSUE 15 | APRIL 11-17, 2019 EDITORIAL MANAGING EDITOR/ FILM EDITOR: Devin D. O’Leary (ext. 230) [email protected] MUSIC EDITOR/NEWS EDITOR: August March (ext. 245) [email protected] FOOD EDITOR: Email letters, including author’s name, mailing address and daytime phone number to [email protected]. Dan Pennington (Ext. 255) [email protected] Letters can also be mailed to P.O. Box 81, Albuquerque, N.M., 87103. Letters—including comments posted ARTS AND LIT.EDITOR: Clarke Condé [email protected] on alibi.com—may be published in any medium and edited for length and clarity; owing to the volume of COPY EDITOR: correspondence, we regrettably can’t respond to every letter. Samantha Carrillo (ext. 223) [email protected] CALENDARS EDITOR: Ashli Kesali [email protected] STAFF WRITER: Joshua Lee (ext. 243) [email protected] Methane Goes Bust the gas pump. Why should citizens have to SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR: Samantha Carrillo (ext. 223) [email protected] have lung-destroying toxics forming in New CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Dear Editor, Mexico’s air? Those are fugitive emissions Robin Babb, Rob Brezsny, Carolyn Carlson, Samantha On “Methane Goes Boom!” [Alibi v28 i14]: Carrillo, Desmond Fox, Maggie Grimason, Steven Luthy, going on for decades. -

Andrew's Schizophrenia in Shutter Island by Dennis Lehane Thesis

ANDREW’S SCHIZOPHRENIA IN SHUTTER ISLAND BY DENNIS LEHANE THESIS Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Bachelor Degree of English Department Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Sunan Ampel Surabaya University By: Shafira Azhari Salsabila Reg. Number: A73215072 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES SUNAN AMPEL STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SURABAYA 2019 ii digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id vi digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id vii digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id viii digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id ABSTRACT Salsabila, Shafira Azhari. 2019. Andrew’s Schizophrenia in Shutter Island by Dennis Lehane. English Department. Faculty of Arts and Humanities. Sunan Ampel State Islamic University. Thesis Advisor : Sufi Ikrima Sa’adah, M.Hum. Key Terms : Psychoanalysis, Schizophrenia, Defense Mechanism. This thesis discusses Andrew’s schizophrenia and its treatment in Shutter Island by Dennis Lehane. Andrew is described to have schizophrenia due to traumatic events. The traumatic events including his guilt of killing hundreds of unarmed soldier during World War II and Andrew’s guilt of not taking his wife, Dolores to psychiatrists that led her to murder her three children, resulting on Andrew ended up killing her with no other choice and lost his entire family. -

Space, Politics, and the Uncanny in Fiction and Social Movements

MADNESS AS A WAY OF LIFE: SPACE, POLITICS AND THE UNCANNY IN FICTION AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Justine Lutzel A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2013 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Francisco Cabanillas Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Gorsevski William Albertini © 2013 Justine Lutzel All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor Madness as a Way of Life examines T.V. Reed’s concept of politerature as a means to read fiction with a mind towards its utilization in social justice movements for the mentally ill. Through the lens of the Freudian uncanny, Johan Galtung’s three-tiered systems of violence, and Gaston Bachelard’s conception of spatiality, this dissertation examines four novels as case studies for a new way of reading the literature of madness. Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House unveils the accusation of female madness that lay at the heart of a woman’s dissatisfaction with domestic space in the 1950s, while Dennis Lehane’s Shutter Island offers a more complicated illustration of both post-traumatic stress syndrome and post-partum depression. Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Curtis White’s America Magic Mountain challenge our socially- accepted dichotomy of reason and madness whereby their antagonists give up success in favor of isolation and illness. While these texts span chronology and geography, each can be read in a way that allows us to become more empathetic to the mentally ill and reduce stigma in order to effect change. -

Video 108 Media Corp 9 Story A&E Networks A24 All Channel Films

Video 108 Media Corp 9 Story A&E Networks A24 All Channel Films Alliance Entertainment American Cinema Inspires American Public Television Ammo Content Astrolab Motion Bayview Entertainment BBC Bell Marker Bennett-Watt Entertainment BidSlate Bleecker Street Media Blue Fox Entertainment Blue Ridge Holdings Blue Socks Media BluEvo Bold and the Beautiful Brain Power Studio Breaking Glass BroadGreen Caracol CBC Cheng Cheng Films Christiano Film Group Cinedigm Cinedigm Canada Cinema Libre Studio CJ Entertainment Collective Eye Films Comedy Dynamics Content Media Corp Culver Digital Distribution DBM Films Deep C Digital DHX Media (Cookie Jar) Digital Media Rights Dino Lingo Disney Studios Distrib Films US Dreamscape Media Echelon Studios Eco Dox Education 2000 Electric Entertainment Engine 15 eOne Films Canada Epic Pictures Epoch Entertainment Equator Creative Media Everyday ASL Productions Fashion News World Inc Film Buff Film Chest Film Ideas Film Movement Film UA Group FilmRise Filmworks Entertainment First Run Features Fit for Life Freestyle Digital Media Gaiam Giant Interactive Global Genesis Group Global Media Globe Edutainment GoDigital Inc. Good Deed Entertainment GPC Films Grasshopper Films Gravitas Ventures Green Apple Green Planet Films Growing Minds Gunpowder & Sky Distribution HG Distribution Icarus Films IMUSTI INC Inception Media Group Indie Rights Indigenius Intelecom Janson Media Juice International KDMG Kew Media Group KimStim Kino Lorber Kinonation Koan Inc. Language Tree Legend Films Lego Leomark Studios Level 33 Entertainment -

Title: Shutter Island Author: Dennis Lehane Description: Summer, 1954

Title: Shutter Island Author: Dennis Lehane Description: Summer, 1954. U.S. Marshal Teddy Daniels has come to Shutter Island, home of Ashecliffe Hospital for the Criminally Insane. Along with his partner, Chuck Aule, he sets out to find an escaped patient, a murderess named Rachel Solando, as a hurricane bears down upon them. But nothing at Ashecliffe Hospital is what it seems. And neither is Teddy Daniels. Is he there to find a missing patient Or has he been sent to look into rumors of Ashecliffes radical approach to psychiatry An approach that may include drug experimentation, hideous surgical trials, and lethal countermoves in the shadow war against Soviet brainwashing ... Or is there another, more personal reason why he has come there As the investigation deepens, the questions only mount: How has a barefoot woman escaped the island from a locked room Who is leaving clues in the form of cryptic codes Why is there no record of a patient committed there just one year before What really goes on in Ward C Why is an empty lighthouse surrounded by an electrified fence and armed guards The closer Teddy and Chuck get to the truth, the more elusive it becomes, and the more they begin to believe that they may never leave Shutter Island. Because someone is trying to drive them insane ... Reviews The New York Times: [A]n eerie, startlingly original story ... [Lehane writes] with a crisp clarity that makes the layout of Shutter Island instantly cinematic ... [A] deft, suspenseful thriller that unfolds with increasing urgency until it delivers a visceral shock in its final moments.