Hop://Cos.Io/ Brian Nosek University of Virginia Hop://Briannosek.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Psychology As a Robust Science Dr Amy Orben Lent Term 2020 When

Psychology as a Robust Science Dr Amy Orben Lent Term 2020 When: Lent Term 2020; Wednesdays 2-4pm (Weeks 0-6; 15.1.2020 – 26.2.2020), Mondays 2-4pm (Week 7; 2.3.2020) Where: Lecture Theatre, Experimental Psychology Department, Downing Site Summary: Is psychology a robust science? To answer such a question, this course will encourage you to think critically about how psychological research is conducted and how conclusions are drawn. To enable you to truly understand how psychology functions as a science, however, this course will also need to discuss how psychologists are incentivised, how they publish and how their beliefs influence the inferences they make. By engaging with such issues, this course will probe and challenge the basic features and functions of our discipline. We will uncover multiple methodological, statistical and systematic issues that could impair the robustness of scientific claims we encounter every day. We will discuss the controversy around psychology and the replicability of its results, while learning about new initiatives that are currently reinventing the basic foundations of our field. The course will equip you with some of the basic tools necessary to conduct robust psychological research fit for the 21st century. The course will be based on a mix of set readings, class discussions and lectures. Readings will include a diverse range of journal articles, reviews, editorials, blog posts, newspaper articles, commentaries, podcasts, videos, and tweets. No exams or papers will be set; but come along with a critical eye and a willingness to discuss some difficult and controversial issues. Core readings • Chris Chambers (2017). -

Promoting an Open Research Culture

Promoting an open research culture Brian Nosek University of Virginia -- Center for Open Science http://briannosek.com/ -- http://cos.io/ The McGurk Effect Ba Ba? Da Da? Ga Ga? McGurk & MacDonald, 1976, Nature Adelson, 1995 Adelson, 1995 Norms Counternorms Communality Secrecy Open sharing Closed Norms Counternorms Communality Secrecy Open sharing Closed Universalism Particularlism Evaluate research on own merit Evaluate research by reputation Norms Counternorms Communality Secrecy Open sharing Closed Universalism Particularlism Evaluate research on own merit Evaluate research by reputation Disinterestedness Self-interestedness Motivated by knowledge and discovery Treat science as a competition Norms Counternorms Communality Secrecy Open sharing Closed Universalism Particularlism Evaluate research on own merit Evaluate research by reputation Disinterestedness Self-interestedness Motivated by knowledge and discovery Treat science as a competition Organized skepticism Organized dogmatism Consider all new evidence, even Invest career promoting one’s own against one’s prior work theories, findings Norms Counternorms Communality Secrecy Open sharing Closed Universalism Particularlism Evaluate research on own merit Evaluate research by reputation Disinterestedness Self-interestedness Motivated by knowledge and discovery Treat science as a competition Organized skepticism Organized dogmatism Consider all new evidence, even Invest career promoting one’s own against one’s prior work theories, findings Quality Quantity Anderson, Martinson, & DeVries, -

The Reproducibility Crisis in Research and Open Science Solutions Andrée Rathemacher University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Creative Commons License

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Technical Services Faculty Presentations Technical Services 2017 "Fake Results": The Reproducibility Crisis in Research and Open Science Solutions Andrée Rathemacher University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/lib_ts_presentations Part of the Scholarly Communication Commons, and the Scholarly Publishing Commons Recommended Citation Rathemacher, Andrée, ""Fake Results": The Reproducibility Crisis in Research and Open Science Solutions" (2017). Technical Services Faculty Presentations. Paper 48. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/lib_ts_presentations/48http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/lib_ts_presentations/48 This Speech is brought to you for free and open access by the Technical Services at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Services Faculty Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Fake Results” The Reproducibility Crisis in Research and Open Science Solutions “It can be proven that most claimed research findings are false.” — John P. A. Ioannidis, 2005 Those are the words of John Ioannidis (yo-NEE-dees) in a highly-cited article from 2005. Now based at Stanford University, Ioannidis is a meta-scientist who conducts “research on research” with the goal of making improvements. Sources: Ionnidis, John P. A. “Why Most -

2020 Impact Report

Center for Open Science IMPACT REPORT 2020 Maximizing the impact of science together. COS Mission Our mission is to increase the openness, integrity, and reproducibility of research. But we don’t do this alone. COS partners with stakeholders across the research community to advance the infrastructure, methods, norms, incentives, and policies shaping the future of research to achieve the greatest impact on improving credibility and accelerating discovery. Letter from the Executive Director “Show me” not “trust me”: Science doesn’t ask for Science is trustworthy because it does not trust itself. Transparency is a replacement for trust. Transparency fosters self-correction when there are errors trust, it earns trust with transparency. and increases confidence when there are not. The credibility of science has center stage in 2020. A raging pandemic. Partisan Transparency is critical for maintaining science’s credibility and earning public interests. Economic and health consequences. Misinformation everywhere. An trust. The events of 2020 make clear the urgency and potential consequences of amplified desire for certainty on what will happen and how to address it. losing that credibility and trust. In this climate, all public health and economic research will be politicized. All The Center for Open Science is profoundly grateful for all of the collaborators, findings are understood through a political lens. When the findings are against partners, and supporters who have helped advance its mission to increase partisan interests, the scientists are accused of reporting the outcomes they want openness, integrity, and reproducibility of research. Despite the practical, and avoiding the ones they don’t. When the findings are aligned with partisan economic, and health challenges, 2020 was a remarkable year for open science. -

The Trouble with Scientists How One Psychologist Is Tackling Human Biases in Science

How One Psychologist Is Tackling Human Biases in Science http://nautil.us/issue/24/error/the-trouble-with-scientists Purchase This Artwork BIOLOGY | SCIENTIFIC METHOD The Trouble With Scientists How one psychologist is tackling human biases in science. d BY PHILIP BALL ILLUSTRATION BY CARMEN SEGOVIA MAY 14, 2015 c ADD A COMMENT f FACEBOOK t TWITTER m EMAIL U SHARING ometimes it seems surprising that science functions at all. In 2005, medical science was shaken by a paper with the provocative title “Why most published research findings are false.”1 Written by John Ioannidis, a professor of medicine S at Stanford University, it didn’t actually show that any particular result was wrong. Instead, it showed that the statistics of reported positive findings was not consistent with how often one should expect to find them. As Ioannidis concluded more recently, “many published research findings are false or exaggerated, and an estimated 85 percent of research resources are wasted.”2 It’s likely that some researchers are consciously cherry-picking data to get their work published. And some of the problems surely lie with journal publication policies. But the problems of false findings often begin with researchers unwittingly fooling themselves: they fall prey to cognitive biases, common modes of thinking that lure us toward wrong but convenient or attractive conclusions. “Seeing the reproducibility rates in psychology and other empirical science, we can safely say that something is not working out the way it should,” says Susann Fiedler, a behavioral economist at the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods in Bonn, Germany. -

Researchers Overturn Landmark Study on the Replicability of Psychological Science

Researchers overturn landmark study on the replicability of psychological science By Peter Reuell Harvard Staff Writer Category: HarvardScience Subcategory: Culture & Society KEYWORDS: psychology, psychological science, replication, replicate, reproduce, reproducibility, Center for Open Science, Gilbert, Daniel Gilbert, King, Gary King, Science, Harvard, FAS, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Reuell, Peter Reuell Summary: A 2015 study claiming that more than half of all psychology studies cannot be replicated turns out to be wrong. Harvard researchers have discovered that the study contains several statistical and methodological mistakes, and that when these are corrected, the study actually shows that the replication rate in psychology is quite high – indeed, it is statistically indistinguishable from 100%. RELATED LINKS: According to two Harvard professors and their collaborators, a 2015 landmark study showing that more than half of all psychology studies cannot be replicated is actually wrong. In an attempt to determine the replicability of psychological science, a consortium of 270 scientists known as The Open Science Collaboration (OSC) tried to replicate the results of 100 published studies. More than half of them failed, creating sensational headlines worldwide about the “replication crisis” in psychology. But an in-depth examination of the data by Daniel Gilbert (Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology at Harvard University), Gary King (Albert J. Weatherhead III University Professor at Harvard University), Stephen Pettigrew (doctoral student in the Department of Government at Harvard University), and Timothy Wilson (Sherrell J. Aston Professor of Psychology at the University of Virginia) has revealed that the OSC made some serious mistakes that make this pessimistic conclusion completely unwarranted: The methods of many of the replication studies turn out to be remarkably different from the originals and, according to Gilbert, King, Pettigrew, and Wilson, these “infidelities” had two important consequences. -

Open Science 1

Running head: OPEN SCIENCE 1 Open Science Barbara A. Spellman, University of Virginia Elizabeth A. Gilbert, Katherine S. Corker, Grand Valley State University Draft of: 20 September 2017 OPEN SCIENCE 2 Abstract Open science is a collection of actions designed to make scientific processes more transparent and results more accessible. Its goal is to build a more replicable and robust science; it does so using new technologies, altering incentives, and changing attitudes. The current movement toward open science was spurred, in part, by a recent series of unfortunate events within psychology and other sciences. These events include the large number of studies that have failed to replicate and the prevalence of common research and publication procedures that could explain why. Many journals and funding agencies now encourage, require, or reward some open science practices, including pre-registration, providing full materials, posting data, distinguishing between exploratory and confirmatory analyses, and running replication studies. Individuals can practice and promote open science in their many roles as researchers, authors, reviewers, editors, teachers, and members of hiring, tenure, promotion, and awards committees. A plethora of resources are available to help scientists, and science, achieve these goals. Keywords: data sharing, file drawer problem, open access, open science, preregistration, questionable research practices, replication crisis, reproducibility, scientific integrity Thanks to Brent Donnellan (big thanks!), Daniël Lakens, Calvin Lai, Courtney Soderberg, and Simine Vazire OPEN SCIENCE 3 Open Science When we (the authors) look back a couple of years, to the earliest outline of this chapter, the open science movement within psychology seemed to be in its infancy. -

Improving Reproducibility in Research: the Role of Measurement Science

Volume 124, Article No. 124024 (2019) https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.124.024 Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology Improving Reproducibility in Research: The Role of Measurement Science Robert J. Hanisch1, Ian S. Gilmore2, and Anne L. Plant1 1National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899, USA 2National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, TW11 0LW, United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Summary: • We report on a workshop held 1–3 May 2018 at the National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, U.K., in which the focus was how the world’s national metrology institutes might help to address the challenges of reproducibility of research. • The workshop brought together experts from the measurement and wider research communities in physical sciences, data analytics, life sciences, engineering, and geological science. The workshop involved 63 participants from metrology laboratories (38), academia (16), industry (5), funding agencies (2), and publishers (2). The participants came from the U.K., the United States, Korea, France, Germany, Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canada, Turkey, and Singapore. • Topics explored how good measurement practice and principles could foster confidence in research findings and how to manage the challenges of increasing volume of data in both industry and research. Key words: confidence; replicability; uncertainty. Accepted: September 5, 2019 Published: September 18, 2019 https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.124.024 1. Motivation and Scope Much has been written in the press recently suggesting that there is a “reproducibility crisis” in scientific research. This stems from well-publicized papers such as those by Brian Nosek et al. -

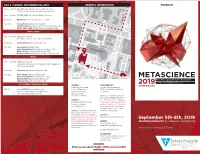

Metascience 2019 Symposium Program

DAY 4 | SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 8th, 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION PROGRAM 6:30 – 7:30 AM Breakfast (Reception Room, Sheraton Palo Alto) **For hosted attendees only, registration required** 8:00 – 9:15 AM FUNDER PANEL: Review and Future Directions Moderator: Brian Nosek Center for Open Science, USA Panelists: Chonnettia Jones Wellcome Trust, UK Dawid Potgieter Templeton World Charity Foundation, BHS Arthur “Skip” Lupia National Science Foundation, USA COFFEE BREAK 9:45 – 11:00 AM PANEL DISCUSSION: Reflections on metascience topics and findings Moderator: Jon Krosnick Stanford University, USA Panelists: Jon Yewdell NIAID/DIR, USA Lisa Feldman Barrett Northeastern University, USA Kathleen Vohs University of Minnesota, USA Norbert Schwarz University of Southern California, USA BREAK 11:15 – 12:30 PM PANEL DISCUSSION: Journalists’ perspective on metascience and engagement with the broader public Moderator: Leif Nelson University of California, USA Panelists: Ivan Oransky Retraction Watch, USA Christie Aschwanden Emerging Form, USA Richard Harris National Public Radio, USA Stephanie M. Lee BuzzFeed News, USA LUNCH BREAK (CENTENNIAL LAWN) ADDRESS TAXI/UBER/LYFT Cubberley Auditorium | Use the following address: 1:30 PM UNCONFERENCE (Centennial Lawn) School of Education | 615 Escondido Road, Stanford, Breakouts, Open Space for Collaboration Stanford University CA 94305 **Beverages & Snacks provided** 485 Lasuen Mall Stanford, CA 94305 Walking to Cubberly Auditorium from Taxi/Uber/Lyft drop-off: It is PARKING a 10-15 minute walk to Cubberley Complimentary Conference Auditorium. Please allow yourself Parking is available plenty of time for a stroll through in the Galvez Lot. the beautiful Stanford Campus! Follow the Metascience signs to Walking to Cubberly Auditorium Cubberley Auditorium. from Galvez Lot: This lot is a 15-20 minute walk from the Cubberley CONTACT Auditorium. -

The Open Science Framework: Improving Science by Making It Open And

OPEN SCIENCE! i! The Open Science Framework: Improving Science by Making It Open and Accessible Jeffrey Robert Spies Bryan, Ohio M.A. Quantitative Psychology, University of Notre Dame, 2007 B.S. Computer Science, University of Notre Dame, 2004 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Psychology University of Virginia May, 2013 OPEN SCIENCE ii Abstract There currently exists a gap between scientific values and scientific practices. This gap is strongly tied to the current incentive structure that rewards publication over accurate science. Other problems associated with this gap include reconstructing exploratory narratives as confirmatory, the file drawer effect, an overall lack of archiving and sharing, and a singular contribution model - publication - through which credit is obtained. A solution to these problems is increased disclosure, transparency, and openness. The Open Science Framework (http://openscienceframework.org) is an infrastructure for managing the scientific workflow across the entirety of the scientific process, thus allowing the facilitation and incentivization of openness in a comprehensive manner. The current version of the OSF includes tools for documentation, collaboration, sharing, archiving, registration, and exploration. OPEN SCIENCE iii Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... ii Table of Contents -

Brian A. Nosek

Last Updated: July 2, 2019 1 BRIAN A. NOSEK University of Virginia, Department of Psychology, Box 400400, Charlottesville, VA 22904-4400 Center for Open Science, 210 Ridge McIntire Rd, Suite 500, Charlottesville, VA 22903-5083 http://briannosek.com/ | http://cos.io/ | [email protected] Positions 2014- Professor University of Virginia 2013- Executive Director Center for Open Science 2008-2014 Associate Professor University of Virginia 2003-2013 Executive Director Project Implicit 2011-2012 Visiting Scholar CASBS, Stanford University 2008-2011 Director of Graduate Studies University of Virginia 2002-2008 Assistant Professor University of Virginia 2005 Visiting Scholar Stanford University 2001-2002 Exchange Scholar Harvard University Education Ph.D. 2002, Yale University, Psychology Thesis: Moderators of the relationship between implicit and explicit attitudes Advisor: Mahzarin R. Banaji M.Phil. 1999, Yale University, Psychology Thesis: Uses of response latency in social psychology M.S. 1998, Yale University, Psychology Thesis: Gender differences in implicit attitudes toward mathematics B.S. 1995, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, Psychology Minors: Computer Science and Women's Studies Center for Open Science: co-Founder, Executive Director Web site: http://cos.io/ Primary infrastructure: http://osf.io/ A non-profit organization that aims to increase openness, integrity, and reproducibility of research. Building tools to facilitate scientists’ workflow, project management, transparency, and sharing. Community-building for open science practices. Supporting metascience research. Project Implicit: co-Founder Information Site: http://projectimplicit.net/ Research and Education Portal: https://implicit.harvard.edu/ Project Implicit is a multidisciplinary collaboration and non-profit for research and education in the social and behavioral sciences, especially for research in implicit social cognition. -

Dr. Brian Nosek, Co-Founder and Executive Director, Center for Open

1 Testimony of Brian A. Nosek, Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Open Science Professor Department of Psychology University of Virginia Before the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology U.S. House of Representatives November 13, 2019 “Strengthening Transparency or Silencing Science? The Future of Science in EPA Rulemaking” Chairwoman Johnson, Ranking Member Lucas, and Members of the Committee, on behalf of myself and the Center for Open Science, thank you for the opportunity to discuss the role of promoting transparency and reproducibility for maximizing the return on research investments, and responsible management of research transparency with competing interests of privacy protections for sensitive data. The bottom line summary of my remarks is: 1. Making open the default for research plans, data, materials, code, and outcomes will reduce friction in discovery and maximize return on research investments 2. Extending existing policy frameworks about transparency and openness across federal agencies will help improve research efficiency. These frameworks can help decision-makers navigate situations in which principles of security and privacy are in conflict with principles of transparency and openness. 3. Rulemaking should be informed by the best available evidence. Sometimes the best available evidence is based on data that cannot be transparent, has high uncertainty, or has unknown reproducibility. Developing tools that clarify uncertainty will improve policymaking and shape research priorities. I joined the faculty at the University of Virginia in the Department of Psychology in 2002. My substantive areas of expertise are research methodology, implicit bias, and the gap between values and practices. In 2013, Jeff Spies and I launched the Center for Open Science (COS) out of my lab as a non-profit technology and culture change organization.