Cyclist Group Identity As Expressed Through Folk Art, Folk Events, Narratives, and Community Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MTB/ASPHALT BIKES FALL 2009 2 I N T R O D U C T I O N

MTB/ASPHALT BIKES FALL 2009 2 I n t r o d u c t i o n History. It has shaped the world we’re living national, and world championships that have Over the years, we’ve learned a thing or two in today. Just about every aspect of our life been won on our bikes. about building bikes. Our bikes are designed is based on what happened in the past. by riders, for riders…they always have been Think a company who’s better known for its Bicycles really aren’t any different. Each and always will be. We wouldn’t dream of BMX bikes can’t make other types of bikes? brand has its own unique niche that has putting you on a bike we wouldn’t ride our- Think again. BMX races are brutally short been shaped over time much like a river selves. We demand quality, performance, and the courses are punishing. Same goes carves a canyon through the Earth’s outer and durability out of each bicycle we pro- for BMX freestyle parks and dirt jumps. A crust of dirt. duce. winning BMX bike needs to maximize trac- Here at Haro Bicycles, we’ve done our fair tion, harness every ounce of pedaling effort, So whether you live for sweet singletrack or share of carving paths through dirt over the and be strong enough to survive the big hits simply cruising your local bike path, Haro has years. Our roots are solid in the stuff; we got but light enough not to be a drag. -

Copake Auction Inc. PO BOX H - 266 Route 7A Copake, NY 12516

Copake Auction Inc. PO BOX H - 266 Route 7A Copake, NY 12516 Phone: 518-329-1142 December 1, 2012 Pedaling History Bicycle Museum Auction 12/1/2012 LOT # LOT # 1 19th c. Pierce Poster Framed 6 Royal Doulton Pitcher and Tumbler 19th c. Pierce Poster Framed. Site, 81" x 41". English Doulton Lambeth Pitcher 161, and "Niagara Lith. Co. Buffalo, NY 1898". Superb Royal-Doulton tumbler 1957. Estimate: 75.00 - condition, probably the best known example. 125.00 Estimate: 3,000.00 - 5,000.00 7 League Shaft Drive Chainless Bicycle 2 46" Springfield Roadster High Wheel Safety Bicycle C. 1895 League, first commercial chainless, C. 1889 46" Springfield Roadster high wheel rideable, very rare, replaced headbadge, grips safety. Rare, serial #2054, restored, rideable. and spokes. Estimate: 3,200.00 - 3,700.00 Estimate: 4,500.00 - 5,000.00 8 Wood Brothers Boneshaker Bicycle 3 50" Victor High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle C. 1869 Wood Brothers boneshaker, 596 C. 1888 50" Victor "Junior" high wheel, serial Broadway, NYC, acorn pedals, good rideable, #119, restored, rideable. Estimate: 1,600.00 - 37" x 31" diameter wheels. Estimate: 3,000.00 - 1,800.00 4,000.00 4 46" Gormully & Jeffrey High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle 9 Elliott Hickory Hard Tire Safety Bicycle C. 1886 46" Gormully & Jeffrey High Wheel C. 1891 Elliott Hickory model B. Restored and "Challenge", older restoration, incorrect step. rideable, 32" x 26" diameter wheels. Estimate: Estimate: 1,700.00 - 1,900.00 2,800.00 - 3,300.00 4a Gormully & Jeffery High Wheel Safety Bicycle 10 Columbia High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle C. -

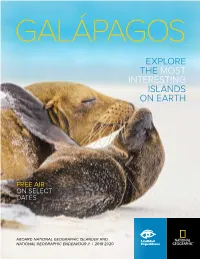

Explore the Most Interesting Islands on Earth

GALÁPAGOS EXPLORE THE MOST INTERESTING ISLANDS ON EARTH FREE AIR ON SELECT DATES ABOARD NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC ISLANDER AND NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC ENDEAVOUR II | 2018-2020 TM DEAR TRAVELER, Galápagos straddles the equator, is mercifully absent of hurricanes and cyclones, and fluctuates little weather-wise throughout the year. The animals are always there for us to observe up-close and personally. It is a geography that’s infinitely compelling, something you already know from countless magazine articles, nature programs, documentaries and more. But what you might not know is that it is the preeminent, guaranteed, slam-dunk vacation option for families. It offers something for everyone. And even better, it offers so much for families to share—it’s where meaningful memories get made together. Galápagos attracts, at least with us, a very diverse audience, driven largely by times when families travel and don’t. (See the chart at bottom right.) So, while Galápagos is always in season as far as wildlife and wonder are concerned, there are very distinct times to be there based on your preference in travel companions. If you don’t like the pitter patter of children’s feet, you can plan to visit when they’re absent. And if you are planning to explore as a family, and want other kids around, you can rely on the fact that we understand how to meet needs and create opportunities for kids of all ages. We’ve been at this for a very long time, ever since my father pioneered travel here in 1966. Galápagos is a very special place, and we are totally committed to ensuring that our guests get the most out of their time here. -

Rule Changes Promise Exciting Season

Online Guide to the main events of the English POLO season FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Saturday May 26 2012 ft.com/polo www.ft.com/polo | twitter.com/ftreports Rule changes promise exciting season Patrons have rethought teams, raising expectations of a year of surprises, writes Bob Sherwood he English high-goal polo sea- son is shaping up to be one of the most open and unpredicta- ble for years, with all of the 16 Tor so teams that will compete at the top level having undergone significant reshuffles of professional players this year. Add to that the return of one of polo’s great forces, Ellerston – whose patron is James Packer, son of Kerry Packer, the late Australian media tycoon and polo enthusiast – to UK high goal for the first time since 2008, and expectations of a classic season have rarely been higher. Unusually, polo insiders have been loath to make predictions. Even the professionals chose to sit on the fence when contributing to the annual Polo Times predictions for the season. “So many teams and combinations have changed that it is difficult to know how it’s going to turn out,” says Max Routledge, the 21-year-old five- goal professional and one of the Eng- lish game’s rising stars. Alterations to handicaps forced Alterations designed to speed up the game and stop the best players from hogging the ball have contributed to some surprising results Reuters some of the changes. However, Routledge believes changes to polo’s best option. The combined handicap of includes Luke Tomlinson, the Eng- Cartier, the jewellery maker, switched rule book in 2011, designed to speed a high-goal team must not exceed 22. -

DECEMBER 6-19, 2018 ORWOODQ EWSQ Nvol

Proudly Serving Bronx Communities Since 1988 3URXGO\6HUYLQJ%URQ[&RPPXQLWLHV6LQFHFREE 3URXGO\6HUYLQJ%URQ[&RPPXQLWLHV6LQFHFREE ORWOODQ EWSQ NVol. 27, No. 8 PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION N April 17–30, 2014 Vol 31, No 24 • PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION • DECEMBER 6-19, 2018 ORWOODQ EWSQ NVol. 27, No. 8 PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION N April 17–30, 2014 FREE INQUIRING PHOTOGRAPHER: MTA: MOSHOLU PKWY. STATION CRIME CONCERNS | PG. 4 MAY GET ELEVATOR DOWN THE LINE | PG. 2 $3 MIL ROOF FIX FOR Hull Avenue Fire Victims Get Help pg 3 Pichardo securesBAILEY funding; hopes HOUSES to see repairs by next year In Norwood, a Mobile Library pg 8 Photo by David Cruz CB7 Rejects Bedford TIESHA JONES (AT MIC), Bailey Houses Residents Council president, speaks at a news conference announcing a $3 million allocation by Assemblyman Victor Pichardo (wearing beret) to x Bailey Houses’ roof. Park Buildings Plan pg 10 By JOSEPH KONIG “ T he roof i s ju st absolutely floor of the 20-story build- action to get it done hope- Assemblyman Victor in complete disrepair,” Pich- ing. And while the $3 mil- fully before the summer… Pichardo has earmarked $3 ardo, flanked by residents, lion in state funding should so when the next cold sea- million in capital funds for said at a news conference on help get the ball moving, the son comes around, the folks roof repairs at the Bailey Dec. 4. “This isn’t something timetable for repairs is still here at Bailey Houses have a Houses, a troubled NYCHA that’s abstract. -

Manuel D'utilisateur

Manuel d‘utilisateur Manuel d’utilisateur AVERTISSEMENT 131515/FR (01/19) CE MANUEL CONTIENT DES INFORMATIONS IMPORTANTES RELATIVES À LA SÉCURITÉ, A LA PERFORMANCE ET À LA MAINTENANCE. Lisez-le et conservez-le précieusement avant la première utilisation de votre vélo. Contacter GT GT USA Cycling Sports Group, Inc. 1 Cannondale Way, Wilton CT, 06897, USA 1-800-726-BIKE (2453) www.gtbikes.com GT EUROPE Cycling Sports Group Europe B.V Mail: Postbus 5100 Visits: Hanzepoort 27 7575 DB, Oldenzaal, Netherlands GT UK Cycling Sports Group Vantage Way, The Fulcrum, Poole, Dorset, BH12 4NU +44 (0)1202732288 [email protected] This manual meets: 16 CFR 1512 and EN Standards 14764, 14766, and 14781. Vélo certifié conforme aux exigences du décret N 95-937 du 24 août 1995 norme NFR030 UTILISATION DE CE MANUEL Autres manuels et instructions Beaucoup de composants de votre vélo n’ont pas été fabriqués par GT bicycles. S’ils sont disponibles auprès des fabricants, GT bicycles joindra ces manuels et/ou Manuel du propriétaire d’un vélo GT instructions à votre vélo. Nous vous recommandons bicycles vivement de lire et de suivre toutes les instructions spécifiques aux fabricants fournies avec votre vélo. Ce manuel contient des informations importantes relatives à votre sécurité et à l’utilisation correcte des Revendeurs GT bicycles agréés vélos. Ce manuel est très important pour tous les vélos Votre revendeur GT bicycles agréé est votre premier que nous fabriquons. Il se compose de deux parties : contact pour l’entretien et le réglage de votre vélo, pour PARTIE I vous explique le fonctionnement et pour toute question concernant la garantie. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Lifestyle, Identity and Young People's Experiences of Mountain Biking

Freeride area at Bedgebury Forest Research Note Lifestyle, identity and young people’s experiences of mountain biking Katherine King December 2010 It has been widely recognised that, for young people, experiencing the natural environment may hold multiple benefits for well-being and the future development of healthy lifestyles. The Active England programme awarded funding aimed at increasing participation in sport and physical activity at Bedgebury Forest in Kent, with a particular emphasis on young people as a key target group. Mountain biking, as a popular youth sport that often occurs in woodlands, was promoted under the scheme and provides the case study upon which this Note is based. The research employed ethnographic techniques to capture youth experiences and understandings of mountain biking and to investigate the resulting relation- ships young people developed with countryside spaces. Methods included semi-structured interviews that allowed for flexibility, ‘mobile’ methods such as accompanied and unaccompanied recorded rides and participant observation. The research reveals the different riding philosophies, lifestyle values and relationships with the landscape that are formed as part of youth mountain biking lifestyles. The research shows that certain countryside spaces, especially woodlands are important for youth leisure. They afford a space away from the gaze of adults and from the conflicts associated with other (urban) leisure space, and provide opportunities to feel ownership. Bedgebury Forest offered a range of ‘ready made’ mountain biking spaces for both beginner and more experienced youth mountain bikers that participants could access without fear of reprimand. This was in sharp contrast to their experiences of other privately owned spaces. -

January 2021 - Diy Plans Catalog

JANUARY 2021 - DIY PLANS CATALOG Anyone Can Do This! Our DIY Plans detail every aspect of the building process using easy to follow instructions with high resolution pictures and diagrams. Even if this is your first attempt at building something yourself, you will be able to succeed with our plans, as no previous expertise is assumed. Detailed Plans – Instant Download! We use real build photos and detailed diagrams instead of complex drawings, so anyone with a desire to build can succeed. Our bike and trike plans are not engineering blueprints, and do not call for hard-to-find parts or expensive tools. DIY Means Building Yourself a Better Life. Unleash your creativity, and turn your drawing board ideas into reality. You don't need a fancy garage full of tools or an unlimited budget to build anything shown on our DIY site, you just need the desire to do it yourself. Take pride in your home built projects, and create something completely unique from nothing more than recycled parts. AURORA DIY SUSPENSION TRIKE PLAN The Aurora Delta Recumbent Trike merges speed, handling, and comfort into one great looking ride! With under seat steering, and rear suspension, you will be enjoying your laid-back country cruises in pure comfort and style. Of course, The Aurora DIY Trike is also a hot performer, and will get you around as fast as your leg powered engine feels like working. This DIY Plan Contains 198 Pages and 203 Photos. Click above for more information. WARRIOR LOW RACER TADPOLE TRIKE PLAN The Warrior is one fast and great looking DIY Tadpole Trike that you can make using only basic tools and parts. -

Bike Polo Story

FORewoRD The game of bicycle polo was conceived in 1891 and is a direct descendant of the very ancient game of horse polo which dates back to 600 BC, and the modern game of hardcourt bike polo - one of the world’s fastest growing urban sports is considered the edgier first cousin of the 19th century grass version. From its genesis in late 19th century Ireland through to its modern day incarnation, this book unravels the history of this fascinating and misunderstood sport. It charts key moments, explores the games pioneers and gets under the skin of some of today’s star exponents. And there are some surprises along the way… Before Hoy, Pendleton, Farah and Ennis cast a golden glow over London 2012, 104 years earlier, bike polo pedalled into the 1908 London Olympics as an exhibition sport. And it may surprise you to know that Princes; Phillip, Wills and Harry have all be known to ditch the horse in favour of the bike… This is the compelling and eventful story of the history of bike polo. Enjoy the journey… 1891 Bicycle Polo, a game of strenuous amusement is born... n 1891, having retired from racing – ‘ordinary’ and tricycle – the Irish cycling Ienthusiast Richard J McCready (hereafter referred to as ‘RJ’) set about inventing a game that would provide ‘strenuous amusement’ and a welcome diversion from editing his beloved Irish Cyclist. His invention? ‘Polo on Wheels’. Following the inaugural game at the Scalp in Co. Wicklow, Richard J McCready Cycling magazine observed the following: “the game of cycling polo promises to be immensely popular…and not at all so dangerous as would appear from the title.” Quick to show his hand was the mysterious Cosmo- Cyclo who wrote an enthusiastic letter published in Cycling stating that since the introduction of pneumatic tyres “cycle polo is not only possible but exciting and enjoyable too!” In Ireland, the sport rapidly gained momentum, with the wider racing fraternity quickly picking up on the benefits of a game that would efficiently hone “..the hands, the head and the eye..” of the racing man. -

Order Cuts 5 County Towns by BEN VAN VL1ET Three-Judge 'Federal Court De- Also Gain Point Pleasant, Sen

Okays Senior Citizen Project SEE STORY PAGERS Rain FINAL Rain, heavy at times, today Ked Bank, Fn-ehoW and tonight. Becoming fair l/mg Branch and mild tomorrow. I EDITION 36PAGES Monmoulli County's Outstanding Home Newspaper TEN CENTS VOL.94 NO.206 RED BANK, NJ. THURSDAY, APRIL 13,1972 iiniiiiaiuuuuuiHUBiauuiBiuni inmiNimuHiuitHHiiiiiiiuiBnimiiiiii iiiiituittiiHHiiutiwHHiiin luiiiiiiiniiniiiiiiiiiiiHimiMiiiHiuuaiuuiiiutiiiiiimiiiuiiiiiiiiiii Order Cuts 5 County Towns By BEN VAN VL1ET three-judge 'federal court de- also gain Point Pleasant, Sen. James Turner, R- gen, Hudson and Essex Coun- Gibbons of the 3rd U.S. Cir- cumbents placed in the same The ideal population per dis- vised a plan which could lead Point Pleasant Beach and Gloucester. It puts East Or- ties would shrink to five. cuit Court of Appeals and U.S. district. trict is 478,059 persons, the NEWARK- Five Mon- to the election of the state's Lakewood. ange, Glen Ridge and Newark According to sources in the District Court Judge Leonard Gallagher was indicted court said. The greatest de- mouLli County municipalities first black congressman. Regrets Loss in Essex County into a district legislature, Democrats could I. Garth voted for the plan. Friday on income tax evasion viation from that Is the 8th will find themselves aligned Monmouth County would re- William F. Dowd, one of with Harrison in Hudson lose one or two of the 9 seats Fisher said he would deliver a charges and it was not clear district, Passaic County, with a new congressional dis- main essentially the Third three contenders for the Re- County. they now hold. The state's dissenting opinion at a later what effect the redistricting which has 385 more people trict encompassing parts of Congressional District, al- publican nomination to oppose This district, the 10th, would congressional delegation is 15. -

Design and Built of Bicycle Chopper Hybrid (BCH) Via Project Based Online Learning (PBOL) an Engineering Students Project Development Md

19382 Md. Baharuddin Bin Haji Abdul Rahman et al./ Elixir Mech. Engg. 64 (2013) 19382-19389 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Mechanical Engineering Elixir Mech. Engg. 64 (2013) 19382-19389 Design and built of Bicycle Chopper Hybrid (BCH) via Project Based Online Learning (PBOL) an engineering students project development Md. Baharuddin Bin Haji Abdul Rahman 1, Hairul Nizam Bin Ismail 2 and Khairul Azhar Bin Mat Daud 3 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, Politeknik Kota Bharu (PKB), Km 24, Pangkal Kalong, 16450 Ketereh, Kelantan, Malaysia. 2School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Penang, Malaysia. 3Falcuty of Technology Creative & Heritage, University Malaysia Kelantan (UMK), 16070, Bachok, Kelantan, Malaysia. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Methods of design and built become new invention of Outcome Based Education (OBE) at Received: 22 September 2013; Politeknik Kota Bharu (PKB). This paper prefer to the process of development Bicycle Received in revised form: Chopper Hybrid (BCH) with Project Based Online Learning (PBOL) match with OBE that 5 November 2013; implemented at PKB. The Project Based Online Learning (PBOL) was implemented based Accepted: 14 November 2013; on online learning management system call eSOLMS for this project development. This process related with engineering survey, planning, design and development of BCH by Keywords using sophisticated technology combination with mechanical machines at inside/outside of Design & Built, workshops at Politeknik Kota Bharu (PKB). The concept of Hybrid vehicle become the new Bicycle Chopper Hybrid (BCH)., innovation ideas for outcome based project 2012. The product of BCH generate with the Outcome Based Education (OBE), power of 1400 rpm motor's to mobilize this vehicle machine.