I WAYWARD STORIES: a RHETORIC of COMMUNITY in WRITING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World's Largest Selection of Christian Songbooks!

19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 1 The world’s largest selection of Christian songbooks! Hal Leonard is proud to be the distributor for Nashville-based Brentwood-Benson. Their extensive catalog offers something for everyone – great new releases from the hottest CCM artists to traditional and contemporary gospel collection. This brochure features just a sampling of Brentwood-Benson’s outstanding artist collections, song compilations, and songbook series. All of these titles are in stock and ready for you to order! Contact your Hal Leonard sales representative to place your order and find out about our Brentwood-Benson special offer! Call the E-Z Order Line at 1-800-554-0626 Send a message to [email protected] or visit www.halleonard.com/dealers 19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 2 MIXED FOLIOS Amazing Wedding Songs Top 100 Praise and Worship Top 100 Praise & Worship Top 100 Southern Gospel 30 of the Most Requested Songs – Volume 2 Songbook Songbook BRENTWOOD-BENSON Songs for That Special Day This guitar chord songbook includes: Ah, Lord Guitar Chord Songbook Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- Book/CD Pack God • Celebrate Jesus • Glorify Thy Name • Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- grams for 100 classics, including: Because He Listening CD – 5 songs Great Is Thy Faithfulness • How Majestic Is grams for 100 songs, including: As the Deer • Lives • Daddy Sang Bass • Gettin’ Ready to ✦ Includes: Always • Ave Maria • Butterfly Your Name • In the Presence of Jehovah • My Come, Now Is the Time to Worship • I Could Leave This World • He Touched Me • In the Kisses • Canon in D • Endless Love • I Swear Savior, My God • Soon and Very Soon • Sing of Your Love Forever • Lord, I Lift Your Sweet By and By • I’ve Got That Old Time • Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring • Love Will Be Victory Chant • We Have Come into This Name on High • Open the Eyes of My Heart • Religion in My Heart • Just a Closer Walk with Our Home • Ode to Joy • The Keeper of the House • and many more! Rock of Ages • and dozens more. -

Pg0140 Layout 1

New Releases HILLSONG UNITED: LIVE IN MIAMI Table of Contents Giving voice to a generation pas- Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 sionate about God, the modern Bargains . .20, 21, 38 rock praise & worship band shares 22 tracks recorded live on their Collections . .2–4, 18, 19, 22–27, sold-out Aftermath Tour. Includes 31–33, 35, 36, 38, 39 the radio single “Search My Heart,” “Break Free,” “Mighty to Save,” Contemporary & Pop . .6–9, back cover “Rhythms of Grace,” “From the Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 Inside Out,” “Your Name High,” “Take It All,” “With Everything,” and the Gifts . .back cover tour theme song. Two CDs. Hymns . .26, 27 $ 99 KTCD23395 Retail $14.99 . .CBD Price12 Inspirational . .22, 23 Also available: Instrumental . .24, 25 KTCD28897 Deluxe CD . 19.99 15.99 KT623598 DVD . 14.99 12.99 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 he spring and summer months are often New Releases . .2–5 Tpacked with holidays, graduations, celebra- Praise & Worship . .32–37 tions—you name it! So we had you and all your upcoming gift-giving needs in mind when we Rock & Alternative . .10–13 picked the products to feature on these pages. Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .28–31 You’ll find $5 bargains on many of our best-sell- WOW . .39 ing albums (pages 20 & 21) and 2-CD sets (page Search our entire music and film inventory 38). Give the special grad in yourConGRADulations! life something unique and enjoyable with the by artist, title, or topic at Christianbook.com! Class of 2012 gift set on the back cover. -

AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.36 GB

Page 1 of 28 **AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 songs, 2.8 days, 5.36 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I Am Loved 3:27 The Golden Rule Above the Golden State 2 Highway to Hell TUNED 3:32 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 3 Dirty Deeds Tuned 4:16 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 4 TNT Tuned 3:39 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 5 Back in Black 4:20 Back in Black AC/DC 6 Back in Black Too Slow 6:40 Back in Black AC/DC 7 Hells Bells 5:16 Back in Black AC/DC 8 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:16 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC 9 It's A Long Way To The Top ( If You… 5:15 High Voltage AC/DC 10 Who Made Who 3:27 Who Made Who AC/DC 11 You Shook Me All Night Long 3:32 AC/DC 12 Thunderstruck 4:52 AC/DC 13 TNT 3:38 AC/DC 14 Highway To Hell 3:30 AC/DC 15 For Those About To Rock (We Sal… 5:46 AC/DC 16 Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution 4:13 AC/DC 17 Blow Me Away in D 3:27 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 18 F.S.O.S. in D 2:41 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 19 Here Comes The Sun Tuned and… 4:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 20 Liar in E 3:12 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 21 LifeInTheFastLaneTuned 4:45 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 22 Love Like Winter E 2:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 23 Make Damn Sure in E 3:34 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 24 No More Sorrow in D 3:44 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 25 No Reason in E 3:07 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 26 The River in E 3:18 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 27 Dream On 4:27 Aerosmith's Greatest Hits Aerosmith 28 Sweet Emotion -

2018 Jack Straw Writing Program

2018 Jack Straw Writing Program [00:00:05] Welcome to The Seattle Public Library’s podcasts of author readings and library events. Library podcasts are brought to you by The Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts, visit our web site at w w w dot SPL dot org. To learn how you can help the library foundation support The Seattle Public Library go to foundation dot SPL dot org. [00:00:36] Hi everybody. Thanks so much for being here. I'm Stacia Brandt and I'm the Literature and Humanities program manager here at the Seattle Public Library. [00:00:48] And as we are getting started today I would like to begin by acknowledging that we are gathered together on the ancestral land of the Coast Salish people. We would like to honor their elders past and present and we thank them for their stewardship of this land. Welcome to today's program with the Jack Straw Writers presented in partnership with Jack Straw Cultural Center. We think our author series sponsor Gary Kunis and the Seattle Times for their generous promotional support of library programs. We're also grateful to the Seattle Public Library Foundation private gifts to the foundation from thousands of donors help the library provide free programs and services that touch the lives of everyone in our community. Now I am delighted to welcome Daymond Rendell the twenty eighteen Writers Program curator Daymond is a poet playwright performer and teaching artist. He's performed in venues across the country and has been repeatedly commissioned by both Seattle and Bellevue art museums as teaching artist. -

Recipe First Chapter.Docx

I'm a fair weather friend I'm a colorless hue but I'm willin' to make a deal If You think You can make some faith here inside I'll drive off and marry You I'm only alive with You I can't get by and I won't get through So put me in the river and let me say I do I'm only alive with You1 1 Only Alive, Jars of Clay, Who We Are Instead, 2003 PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com Fiction by Susan McGeown: A Well Behaved Woman’s Life A Garden Walled Around Trilogy: Call Me Bear Call Me Elle Call Me Survivor Rosamund’s Bower Rules for Survival Recipe for Disaster The Butler Did It Joining The Club Nonfiction by Susan McGeown Biblical Women And Who They Hooked Up With PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com Recipe For Disaster By Susan McGeown Published by Faith Inspired Books PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com Magnificent Cover Art courtesy of Laury Vaden [email protected] Published by Faith Inspired Books 3 Kathleen Place, Bridgewater, New Jersey 08807 www.FaithInspiredBooks.com Copyright TXu 1-287-056, February 22, 2006, All Rights Reserved ISBN: 978-0-6151-4608-9 This work is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblances to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales are entirely coincidental. Footnote credits appear throughout this work. PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com To My Sister, Amy, and My Brother - In - Law, Michael And Their International Family: Hannah, Matthew, Jack, and Maggie PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com Prologue 2 Acknowledgements While this is a work of fiction, some characters in this book are inspired by the wonderful people God has allowed to influence my life. -

Making Metadata: the Case of Musicbrainz

Making Metadata: The Case of MusicBrainz Jess Hemerly [email protected] May 5, 2011 Master of Information Management and Systems: Final Project School of Information University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 Making Metadata: The Case of MusicBrainz Jess Hemerly School of Information University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 [email protected] Summary......................................................................................................................................... 1! I.! Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2! II.! Background ............................................................................................................................. 4! A.! The Problem of Music Metadata......................................................................................... 4! B.! Why MusicBrainz?.............................................................................................................. 8! C.! Collective Action and Constructed Cultural Commons.................................................... 10! III.! Methodology........................................................................................................................ 14! A.! Quantitative Methods........................................................................................................ 14! Survey Design and Implementation..................................................................................... -

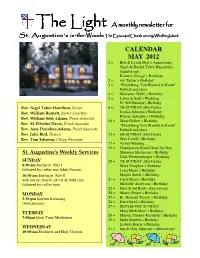

May 2012 – the Light Newsletter-Small Media Format

The Light A monthly newsletter for St. Augustine’s ininin-in ---thethethethe----WoodsWoods The Episcopal Church serving Whidbey Island. CALENDAR MAY 2012 1 = Bob & Lynda Dial’s Anniversary Nigel & Rachel Taber-Hamilton’s Anniversary Kimmie George’s Birthday 2 = Art Taylor’s Birthday 3 = “Everything You Wanted to Know” Potluck and class 4 = Marianne Tuttle’s Birthday 5 = Laura & Seth’s Wedding Fr. Bill Burnett’s Birthday Rev. Nigel Taber-Hamilton, Rector 6 = 5th SUNDAY after Easter Rev. William Burnett, Rector Emeritus Jessica Johnson’s Birthday Kristen Schricker’s Birthday Rev. William Seth Adams, Priest Associate 10 = Mary Hollen’s Birthday Rev. M. Fletcher Davis, Priest Associate “Everything You Wanted to Know” Rev. Amy Donohue-Adams, Priest Associate Potluck and class Rev. Julie Bird, Deacon 13 = 6th SUNDAY after Easter Rev. Tom Johnson, Clergy Associate Max Corell’s Birthday 17 = Vestry Meeting 19 = Honeymoon Road Clean Up Day St. Augustine’s Weekly Services Maureen Masterson’s Birthday Dick Werttemberger’s Birthday SUNDAY 20 = 7th SUNDAY after Easter 8:00 am Eucharist Rite I Mary Vaughan’s Birthday followed by coffee and Adult Forums Lena Mann’s Birthday 10:30 am Eucharist Rite II Maylin Steele’s Birthday with music, church school & child care 21 = Carol Ryan’s Birthday followed by coffee hour Michelle Anderson’s Birthday 22 = Julie & ted Bird’s Anniversary MONDAY 24 = Martin Payne’s Birthday 5:30 pm Solemn Evensong 25 = Br. Richard Tussey’s Birthday (with incense) 26 = Katie Reid’s Birthday 27 = PENTECOST SUNDAY TUESDAY Mary Beth Moss’s Birthday 28 = Marion Pfeiffer-Kornfeld’s Birthday 7:00pm Quiet Time Meditation 30 = Mark Borden’s Birthday Lisbeth Harrje’s Birthday WEDNESDAY 31 = Jan & Gary Johnson’s Anniversary 10:00 am Eucharist and Holy Unction From the Rector I have often wondered what it’s like, liturgically, to be a Christian in the southern hemisphere. -

Topical Listing

CATALOG OF VIDEOS & DVDS 2016 VIDEO GUIDELINES 1. The annual membership fee is $20 for FEC churches, and $40 for other churches. 2. You may request a video by phone, mail, or email at [email protected] 3. All tapes should be returned to FEC Office immediately after completion. 4. Please direct all requests to Lynette Augsburger, 260-423-3649. FEC VIDEO LIST 1420 Kerrway Court Fort Wayne, IN 46805 260-423-3649 The following VHS videotapes are available to churches who are members of the FEC Audio-Visual Library. Materials are checked out on a first-come first-serve basis. If you see that you will be needing a series in the future, feel free to contact the office a few months in advance and reserve the tapes. You are also welcome to preview them ahead of time as they are available. There is no per-tape charge. Churches who are not current members of the FEC Audio-Visual are invited to send their $20 annual membership fee to FEC Resource Center (billed annually in February). Contact the Library if you have suggestions of video’s to add to the Video Library. OPICAL LISTING FEC VIDEO/DVD LIST Page BIBLE STUDY 3:16 – The Church Experience 10 3:16 – The Numbers of Hope 10 A Heart Like His 11 A Woman’s Heart, God’s Dwelling Place 12 Believing God 15 The Beloved Disciple 15 Breaking Free 16 Breath 16 Captivating 17 Case for Christ 18 The Children of the Day 18 Choose the Life 19 Circle Maker 19 Covenant - God’s Enduring Promises 20 Crazy Love 20 Daniel 21 David 21 Deeper Connections Series 22 Defining Moments 24 Desiring God 24 Discerning -

Pg0140 Layout 1

New 3-CD Sets See page 39 See page 3 See page 3 Footer goes here 3 New Releases SONGS 4 WORSHIP ULTIMATE: Table of Contents THE GREATEST PRAISE & WORSHIP SONGS OF ALL Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 TIME—CDS AND DVD Bargains . .20 Praise the Lord with 27 of the Collections 2–8, 20, 21, 24–35, 37, 39, back cover greatest worship songs of all time! Includes “Friend of God” Contemporary & Pop . .8–11 (Israel & New Breed); “Mighty to Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 Save” (Laura Story); “Revelation Gifts . .21, back cover Song” (Phillips, Craig & Dean); “My Savior Lives” (New Life Worship); “Your Grace Is Enough” Hymns . .28–31 (Jared Anderson); “Holy Is the Lord” (Brooklyn Tabernacle Inspirational . .26, 27 Choir); and more. Two CDs and one DVD. Instrumental . .32, 33 $ 99 FJCD50960 Retail $13.99 . .CBD Price11 Karaoke . .23 Kids’ Music . .24, 25, back cover Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 We welcome the rising temperatures for spring and Music DVDs . .38 summer, but we hate to see the cost of gas, food, and other necessities continue to climb as well. Here you’ll find Music/Vocal Instruction . .18, 19 pages upon pages of CDs and DVDs at unbeatable New Releases . .2, 3 prices—making it affordable to splurge for friends, fami- Praise & Worship . .4–7 ly, and yourself! Enhance your personal devotions with instrumental Rock & Alternative . .12, 13 arrangements of favorite worship songs (pages 32 & 33); Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .34–37 check out our unique collector’s edition tins for fans of T-Shirts & Hoodies . .22 Irish music, wedding favorites, bluegrass gospel, Elvis, or more (page 21); and dress your family in clothing that WOW . -

The Lived Experience of Women Engaged in Creative Journaling

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: PAUSING TO CULTIVATE OUR GARDENS: THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF WOMEN ENGAGED IN CREATIVE JOURNALING Sonya Marie Riley Doctor of Philosophy, 2019 Dissertation Directed by: Professor Francine Hultgren Department of Teaching and Learning Policy and Leadership This phenomenological dissertation explores the lived experience of women participating in a creative journaling pause (CJP), a phrase describing the moment in which the participant chooses herself and engages in an activity of expression. Grounded in the tradition of hermeneutic phenomenology, biblical Christian principles, and the philosophical work of Martin Heidegger and Hans-Georg Gadamer, this research focuses on the practice of a creative journaling pause to assist a woman in cultivating her personal garden, in particular herself as an authentic individual. The metaphors of a sand garden and an oasis are used as descriptors to illuminate the phenomenon. The stories of the women hidden in the sand, or the depths of their journal pages, surfaced through our conversations in the moments of our four creative journaling pauses. Each pause, likened to an oasis, gave space to dwell in rest, freedom, and renewal. Thoele (2008) identifies women as “multi-focused, multifaceted, multi-tasking wonders” (p. 21). Yet, the various aspects or roles of a woman’s life may not always align with her ability to focus on self. Thus, the phenomenon of a creative journaling pause intrigues me with what it means to be a woman discovering and rediscovering her authentic self through the actions of pausing and the process of creative journaling. In brief, chapter one turns to the phenomenon and reveals my abiding concern. -

IU Med School Keeps Low Profile University Students Study, Dissect, Resea Employee

/ ^ \ THE U b s e r v e r The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Marys VOLUME 38: ISSUE 94 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 19, 2 0 0 4 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM IU med school keeps low profile University Students study, dissect, resea employee By KEVIN ALLEN struck by News Writer Tucked away in the base ment of Haggar Hall, lies one vehicle of Notre Dame’s best kept secrets — a medical school. Since 1972, Indiana University By ANDREW THAGARD has been renting space in Associate News Editor Haggar Hall for the South Bend Center for Medical A University employee was Education, one of eight centers struck by a vehicle Wednesday in the Indiana University morning as she attempted to Medical School system. cross a stretch of Juniper Road When the South Bend Center adjacent to Grace Hall. first opened, just one IU faculty The female employee, whose member worked there. The identity was not released by rest of the teaching staff was Notre Dame Security/Police made up of Notre Dame facul assistant director Chuck Hurley, ty, primarily from the biochem was attempting to climb over a istry department. The Center snow embankment in. order to was eventually taken over by cross Juniper when she lost her full-time IU faculty, eight of balance and fell onto the road. which are currently on staff. The victim hit her head on the With only 16 students in side of a south bound vehicle as each class at the centers, the she was falling. Hurley said. IU School of Medicine system MICHELLE OTTOZThe Observer A witness and the driver con Students attend class at the South Bend Center for Medical Education located In the basement of tacted police, and police and see MED/page 6 Haggar Hall. -

“Who Am I to Teach and Charge for It?” Candid Reflections to Comfort, Encourage, Caution, and Support

Who am I to Teach and Charge for it? “Who am I to Teach and Charge for it?” Candid Reflections to Comfort, Encourage, Caution, and Support marketingforhippies.com !1 Who am I to Teach and Charge for it? Contents Introduction 4 Comforts & Encouragements 9 Comfort & Encouragement #1: You Deserve to Have Your Needs Met 10 Comfort & Encouragement #2: You May Need to Appoint Yourself 11 Comfort & Encouragement #3: Your Doubts are Often Your Integrity in Disguise 12 Comfort & Encouragement #4: Your Questions About Money are Often About Your Integrity 14 Comfort & Encouragement #5: Doubt is a Part of the Creative Process 16 Comfort & Encouragement #6: You Might Not be Ready, But . 18 Comfort & Encouragement #7: You Have Something to Offer 20 Comfort & Encouragement #8: Don’t Underestimate the Important Gift of Empathy 22 Comfort & Encouragement #9: Almost Everyone is Crap When They Start 23 Comfort & Encouragement #10: Beware of Comparing Your Insides to Other People’s Outsides 25 Comfort & Encouragement #11: You Know More Than You Think You Do 26 Comfort & Encouragement #12: They Don’t Notice What You Notice 27 Comfort & Encouragement #13: To a Third Grader, a Fourth Grader is God 28 Comfort & Encouragement #14: You’ll Improve Faster Than You Think You Will 29 Comfort & Encouragement #15: You’re Going to Fuck Up 30 Comfort & Encouragement #16: Your Failures are Your Credentials 32 Comfort & Encouragement #17: This is Not About Self-Worth 34 Comfort & Encouragement #18: Your Story and Point of View Have Value 35 Comfort & Encouragement #19: