3. Affected Environment, Impacts, and Mitigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Little Fork River, Minnesota 1. the Area

Little Fork River , Minnesota 1. The area surrounding the river: a. The Little Fork watershed is located in Itasca, St. Louis, and Koochichinz Counties, Minnesota. It rises in a rather flat region in St. Louis County and follows a meandering course to the northwest through Koochiching County to its junction with the Rainy River about 19 miles below Little Fork, Minnesota. The area is a hummocky rolling surface made up of morainic deposits and glacial drift laid over a bedrock composed largely of granitic, volcanic, and metamorphic rocks. The upper basin is covered with dense cedar forests with some trees up to three feet in diameter. Needles form a thick layer over the ground with ferns turning the forest floor into a green carpet. In the lower basin the forest changes to hardwoods with elm predominating. Dense brush covers the forest floor. Farming is the major land use other than timber production in the area of Minnesota, but terrain limits areas where farming is practical. Transportation routes in this area are good due to its proximity to International Falls, Minnesota, a major border crossing into Canada. U. S. 53 runs north-south to International Falls about 25 miles east of the basin. U. S. 71 runs northeast-southwest and crosses the river at. Little Fork, Minnesota, and follows the U. S. /Canadian border to International Falls. Minnesota Route 217 connects these two major north-south routes in an east-west direction from Little Fork, Minnesota. Minnesota Route 65 follows the river southward from Little Fork, Minnesota. b. Population within a 50-mile radius was estimated at 173, 000 in. -

Conservation Assessment for White Adder's Mouth Orchid (Malaxis B Brachypoda)

Conservation Assessment for White Adder’s Mouth Orchid (Malaxis B Brachypoda) (A. Gray) Fernald Photo: Kenneth J. Sytsma USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region April 2003 Jan Schultz 2727 N Lincoln Road Escanaba, MI 49829 906-786-4062 This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on Malaxis brachypoda (A. Gray) Fernald. This is an administrative study only and does not represent a management decision or direction by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was gathered and reported in preparation for this document and subsequently reviewed by subject experts, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if the reader has information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact: Eastern Region, USDA Forest Service, Threatened and Endangered Species Program, 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for White Adder’s Mouth Orchid (Malaxis Brachypoda) (A. Gray) Fernald 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..............................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION/OBJECTIVES ...................................................................................................3 -

July/August 2020 Number 7/8 $12.00

UUns United Northern Sportmen’s News Conservation Pledge: I give my pledge as an American to save and faithfully to defend from waste, ___________________________________________________________________________________the natural resources of my country - its’ air, soil and minerals, its’ forests, waters and wildlife. VOLUME 65 JULY/AUGUST 2020 NUMBER 7/8 $12.00 UNITED NORTHERN SPORTSMEN’S CLUB Club Calendar CAMPGROUND OPEN July 19 Carry Class, Steve Holt The Board of Directors and club volunteers have completed 9am-4:30pm preparing the campground and other club areas and they are Pistol Range Reserved: open for member’s use. This includes the development and im- 3pm-4:30pm plementation of a DNR COVID-19 Response Plan that allowed us to open the campground on June 1st. We want to thank all July 20-21 Rifle Range Reserved: the volunteers who helped us in this effort. 8am-Noon CANCELLED UNS EVENTS Aug. 3-4 Rifle Range Reserved: 8am-Noon As stated in the last newsletter, due to the COVID-19 pandem- ic, we canceled the spring banquet normally held in April and Aug. 5 UNS Board Meeting the annual walleye fishing contest held in early June. At the 7pm, UNS Retreat June board of directors meeting the board, with regrets, also canceled two other traditional summer events. Our youth field Aug. 17-18 Rifle Range Reserved: day and annual picnic, both held each year in August, will not 8am-Noon be held this year in order to adhere to the governor’s safety guidelines regarding larger group gatherings. At this time we Sept. 2 UNS Board Meeting have no plans to reschedule any of these events later in 2020, 7pm, UNS Retreat but do look forward to resuming them again in 2021. -

1 Minnesota Statutes 2013 89.021 89.021 State Forests

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2013 89.021 89.021 STATE FORESTS. Subdivision 1. Established. There are hereby established and reestablished as state forests, in accordance with the forest resource management policy and plan, all lands and waters now owned by the state or hereafter acquired by the state, excepting lands acquired for other specific purposes or tax-forfeited lands held in trust for the taxing districts unless incorporated therein as otherwise provided by law. History: 1943 c 171 s 1; 1963 c 332 s 1; 1982 c 511 s 9; 1990 c 473 s 3,6 Subd. 1a. Boundaries designated. The commissioner of natural resources may acquire by gift or purchase land or interests in land adjacent to a state forest. The commissioner shall propose legislation to change the boundaries of established state forests for the acquisition of land adjacent to the state forests, provided that the lands meet the definition of forest land as defined in section 89.001, subdivision 4. History: 2011 c 3 s 3 Subd. 2. Badoura State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1; 1967 c 514 s 1; 1980 c 424 Subd. 3. Battleground State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1 Subd. 4. Bear Island State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1 Subd. 5. Beltrami Island State Forest. History: 1943 c 171 s 1; 1963 c 332 s 1; 2000 c 485 s 20 subd 1; 2004 c 262 art 2 s 14 Subd. 6. Big Fork State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1 Subd. 7. Birch Lakes State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1; 2008 c 368 art 1 s 23 Subd. -

1~11~~~~11Im~11M1~Mmm111111111111113 0307 00061 8069

LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE LIBRARY ~ SD428.A2 M6 1986 -1~11~~~~11im~11m1~mmm111111111111113 0307 00061 8069 0 428 , A. M6 1 9 This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) State Forest Recreation Areas Minnesota's 56 state forests contain over 3.2 million acres of state owned lands which are administered by the Department of Natural Resources, Division of Forestry. State forest lands are managed to produce timber and other forest crops, provide outdoor recreation, protect watershed, and perpetuate rare and distinctive species of flora and fauna. State forests are multiple use areas that are managed to provide a sustained yield of renewable resources, while maintaining or improving the quality of the forest. Minnesota's state forests provide unlimited opportunities for outdoor recreationists to pursue a variety of outdoor activities. Berry picking, mushroom hunting, wildflower identification, nature photography and hunting are just a few of the unstructured outdoor activities which can be accommodated in state forests. For people who prefer a more structured form of recreation, Minnesota's state forests contain over 50 campgrounds, most located on lakes or canoe routes. State forest campgrounds are of the primitive type designed to furnish only the basic needs of individuals who camp for the enjoyment of the outdoors. Each campsite consists of a cleared area, fireplace and table. In addition, pit toilets, garbage cans and drinking water may be provided. -

This Document Is Made Available Electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library As Part of an Ongoing Digital Archiving Project

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) Minnesota's .56 state forests contain over 3.2 mill ion needs of individuals who canp for the enjo.J1Tl€11t of the acres of state o.vned lands which are adninisterecr by the outdoors. Each canp:;ite consists of a cleared area, Departrrent of Natural Resources, Division of Forestry. fireplace and table. In addition, pit toilets, garbage State forest 1ands are rranaged to produce timber and cans and drinking water are provided at canp:Jmunds that other forest crops, provide outdoor recreation, protect charge a fee. Sane campgrounds have hiking trails, watershed, and perpetuate rare and distinctive species water access sites and swimning beaches. of flora and fauna. State forests are multiple use areas that are rranagecl to provide a sustained yield of In addition to canpgrounds, over 20 day use areas have renew:i.ble resrurces, while maintaining or irrproving the been developed adjacent to canp:Jmunds or at other quality of the forest. scenic locations within state forests. Day use areas are c011T0nly equipped with picnic tables, fire rings, Minnesota's state forests provide unlimited drinking water, toilets and garbage cans. Many have opportunities for outdoor recreationists to pursue a boat accesses and swimning beaches. variety of outdoor activities. Berry picking, mushroan hunting, wildflov.er identification, nature photography To accarrnodate hikers and skiers, there are more than and hunting are just a fe>J of the unstructured outdoor 150 miles of trails spread throughout the forests. -

Chippewa Area, the DNR Coordinated Its Work with Citizens, the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, County Boards and Land Departments, and the US Forest Service

Forest Classification and Forest Road and Trail Designations for State Forest Lands in and Near the Chippewa National Forest May 31, 2008 Minnesota Department of Natural Resources DNR Chippewa Road & Trail Designation Team Bob Moore ........................................................................................................ Trails & Waterways Michael North .................................................................................................Ecological Resources Keith Simar .......................................................................................................................... Forestry Ken Soring ....................................................................................................................Enforcement Mark Spoden............................................................................................................ Fish & Wildlife Rick Jaskowiak ............................................................................ Geographic Information Systems Jack Olson............................................................................................................................. Planner © 2008, State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources is available to all individuals regardless of race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, status with regard to public assistance, age, sexual orientation, or disability. Discrimination inquiries -

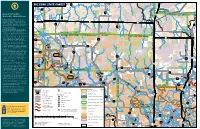

Map of the Big Fork State Forest

BIG FORK STATE FOREST 74,817 ACRES • ESTABLISHED 1963 FOREST LANDSCAPE: Located between Scenic State Park and Northome, Big Fork State Forests feature boreal forests of pine, spruce, and aspen. Many lakes and streams dot the landscape, including picturesque rapids along the Big Fork River. A WORKING FOREST: From year to year, you may see changes in this forest. The DNR manages the trees, water, and wildlife in state forests to keep them healthy and meet recreational, environmental, and economic goals. Trees are harvested to make a variety of products, such as lumber and building materials, pulp for making paper, pallets, fencing, and telephone poles. Through careful planning, harvesting, and planting, land managers work to improve wildlife habitat. The DNR manages state forests for everyone to use, while preventing wildfires and ensuring forests continue to keep air and water clean. HISTORY: After the last ice age, glacial Lake Agassiz inundated the area that is today’s Big Fork State Forest. As the shallow lake slowly drained to the northwest, receding waters deposited clayey to loamy soils. Today, the landscape is mostly flat to slightly rolling. The southern part of the forest, east of Wirt, is hillier, with more lakes. A succession of Woodland Indians occupied the region for at least 2,500 years. The Dakota (or Sioux) inhabited the area until the Ojibwe (Chippewa) arrived. In the late 1800s, a group of Chippewa/Bois Forte lived along the Big Fork River in bark wigwams. Logging between the late 1880s and early 1900s profoundly transformed the area, as millions of board feet of pine logs were floated downstream (north) along the Big Fork to lumber mills in Ontario. -

Bemidji to Grand Rapids 230 Kv Transmission Project

Environmental Report: Bemidji to Grand Rapids 230 kV Transmission Project April 30, 2009 In the Matter of the Application of Otter Tail Power Company, Minnesota Power, and Minnkota Power Cooperative for a Certificate of Need for 230- kV Transmission Line and Associated System Connections from Bemidji to Grand Rapids Minnesota PUC Docket No.E01, E015, ET-6/CN-07-1222 Page Left Intentionally Blank RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT UNIT PROJECT PROPOSERS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Otter Tail Power Company OFFICE OF ENERGY SECURITY Minnesota Power 85 7th Place East, Suite 500 Minnkota Power Cooperative St. Paul, Minnesota 55101‐2198 PROJECT REPRESENTATIVE PROJECT REPRESENTATIVE Suzanne Lamb Steinhauer Bob Lindholm Energy Facility Permitting Manager‐Strategic Environmental 651.296.2888 Initiatives [email protected] Minnesota Power 30 West Superior Street Duluth, MN 55802 (218) 355‐3342 Abstract On March 17, 2008, Otter Tail Power Company, Minnesota Power, and Minnkota Power Cooperative (Applicants) applied for a Certificate of Need (CON) from the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (Commission) to build the proposed Bemidji – Grand Rapids 230 kV Transmission Project (Project). The application was accepted as complete by the Commission on July 22, 2008. The Project is a Large Energy Facility as defined by Minnesota Statute 216B.2421 and requires a CON from the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission. The Project also will require a route permit, which will be reviewed by the Commission in a separate proceeding under Docket 07‐ 1327. An Environmental Report (ER) is required for the CON. The Department of Commerce is responsible for the preparation of this report under Minnesota Rules 7849.7010‐7110. -

Lost 40 SNA Itasca County

Lost 40 SNA Itasca County N47 46.417 W94 4.875 N47 46.290 N47 46.422 W94 4.916 W94 5.405 Big Fork State Forest N47 46.289 W94 4.747 Brook se M o o trail N47 46.140 W94 5.350 N47 46.111 W94 5.183 N47 46.085 W94 5.135 N47 46.053 W94 5.078 N47 46.016 W94 5.150 N47 45.992 Chippewa National Forest W94 5.078 N47 45.984 W94 5.028 Blackduck Area N47 45.988 Parking N47 46.036 W94 4.747 N47 45.970 W94 5.048 W94 5.065 © 2017 MinnesotaSeasons.com. All rights reserved. Based on Minnesota DNR data dated 10/27/2017 Lost 40 SNA Itasca County N47 46.417 W94 4.875 N47 46.290 N47 46.422 W94 4.916 W94 5.405 Big Fork State Forest N47 46.289 W94 4.747 Brook se M o o trail N47 46.140 W94 5.350 N47 46.111 W94 5.183 N47 46.085 W94 5.135 N47 46.053 W94 5.078 N47 46.016 W94 5.150 N47 45.992 Chippewa National Forest W94 5.078 N47 45.984 W94 5.028 Blackduck Area N47 45.988 Parking N47 46.036 W94 4.747 N47 45.970 W94 5.048 W94 5.065 © 2017 MinnesotaSeasons.com. All rights reserved. Based on Minnesota DNR data dated 10/27/2017 Lost 40 SNA Itasca County N47 46.417 W94 4.875 N47 46.290 N47 46.422 W94 4.916 W94 5.405 Big Fork State Forest N47 46.289 W94 4.747 Brook se M o o trail N47 46.140 W94 5.350 N47 46.111 W94 5.183 N47 46.085 W94 5.135 N47 46.053 W94 5.078 N47 46.016 W94 5.150 N47 45.992 Chippewa National Forest W94 5.078 N47 45.984 W94 5.028 Blackduck Area N47 45.988 Parking N47 46.036 W94 4.747 N47 45.970 W94 5.048 W94 5.065 © 2017 MinnesotaSeasons.com. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 89.021

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 89.021 89.021 STATE FORESTS. Subdivision 1. Established. There are hereby established and reestablished as state forests, in accordance with the forest resource management policy and plan, all lands and waters now owned by the state or hereafter acquired by the state, excepting lands acquired for other specific purposes or tax-forfeited lands held in trust for the taxing districts unless incorporated therein as otherwise provided by law. History: 1943 c 171 s 1; 1963 c 332 s 1; 1982 c 511 s 9; 1990 c 473 s 3,6 Subd. 1a. Boundaries designated. The commissioner of natural resources may acquire by gift or purchase land or interests in land adjacent to a state forest. The commissioner shall propose legislation to change the boundaries of established state forests for the acquisition of land adjacent to the state forests, provided that the lands meet the definition of forest land as defined in section 89.001, subdivision 4. History: 2011 c 3 s 3 Subd. 2. Badoura State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1; 1967 c 514 s 1; 1980 c 424; 2018 c 186 s 10 subd 1 Subd. 3. Battleground State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1 Subd. 4. Bear Island State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1; 2016 c 154 s 15 subd 1 Subd. 5. Beltrami Island State Forest. History: 1943 c 171 s 1; 1963 c 332 s 1; 2000 c 485 s 20 subd 1; 2004 c 262 art 2 s 14 Subd. 6. Big Fork State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1 Subd. -

Big Fork River Watershed Monitoring and Assessment Report

z c s Big Fork River Watershed Monitoring and Assessment Report December 2013 Authors The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs MPCA Big Fork River Watershed Report Team: by using the Internet to distribute reports and April Lueck, Jesse Anderson, Mike Kennedy, Nolan information to wider audience. Visit our website Baratono, Dave Christopherson, David Duffey, for more information. Stacia Grayson, Jeff Jasperson, Benjamin Lundeen, MPCA reports are printed on 100 percent post- Bruce Monson, Shawn Nelson, Kris Parson, consumer recycled content paper manufactured Andrew Streitz. without chlorine or chlorine derivatives. Contributors / acknowledgements Citizen Stream Monitoring Program Volunteers Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Minnesota Department of Health Minnesota Department of Agriculture Project dollars provided by the Clean Water Fund (from the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment) Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | www.pca.state.mn.us | 651-296-6300 Toll free 800-657-3864 | TTY 651-282-5332 This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us Document number: wq-ws3-09030006b List of acronyms AUID Assessment Unit Identification MDNR Minnesota Department of Natural Determination Resources CCSI Channel Condition and Stability Index MINLEAP Minnesota Lake Eutrophication CD County Ditch Analysis Procedure CI Confidence Interval MPCA Minnesota Pollution Control Agency CLMP Citizen Lake Monitoring Program MSHA Minnesota Stream