The Impact of Aboriginal Self-Determination on Indigenous Child Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY RESEARCH SCHOOL of PACIFIC STUDIES DEPARTMENT of ECONOMICS ANNUAL R:LPORT, 1964 Professors Pr

,. THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY RESEARCH SCHOOL OF PACIFIC STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS ANNUAL R:LPORT, 1964 Staff Professors H.W. Arndt, M.A., B.Litt., Head of Department J.G. Crawford, Kt., C.B.E., M.Ec. Professorial Fellows D.M. Bensusan-Butt, M. A. W.M. Corden, M.Com., Ph.D. Senior Fellow E.K. Fisk, M.A. Senior Research Fellow Helen Hughes, M.A., Ph.D. (from March) Research Fellows G.B. Hainsworth, B.Sc., Ph.D. B.J. McFarlane, M.Ec. R.H. Myers, M.A., Ph.D. (from June) R. T. Shand, M. Sc . Agr. , Ph.D. K.D. Thomas, M.A. Visiting Fellow T.H. Silcock, M.A., D.Phil. (from September) Research Officer W.F.M. Straatmans Research;Assistants Mrs. N. Anderson, B.A. G.R. Hogbin, B.Sc.Agr. Mrs. H.S. Morley, B.A. (part-time, from September) Mrs. H. V. Richter, M.A. Mrs. M.:L. Rowland, M.A. (part-time) Mrs. M.J . Salter, B.A. (part-time) Mrs . N. Viviani\ B.A. (part-time, from August) Research Programme The main new developments in the Department's fourth year were a decision to embark on a longer-term project of study of the Indonesian economy and the initiation of a group of studies of Australian foreign aid policy. While maintaining some interest, through work by individual staff members or students, in other countries of the Pacific region, the Department intends to concentrate a considerable part of its resources over the next few years on three countries: New Guinea, Malaysia and Indonesia. -

Digest – Graduate Researchers in Academic Positions

Digest – Graduate Researchers in Academic Positions Dr Aren Aizura Graduated with PhD in Cultural Studies in 2009. Assistant Professor in Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies, College of Liberal Arts, University of Minnesota, USA https://cla.umn.edu/about/directory/profile/azaizura Dr Amelia Barikin Graduated with a PhD in Art History in 2008. Lecturer in Art History, School of Communication and Arts, University of Queensland https://researchers.uq.edu.au/researcher/2952 Dr Bobby Benedicto Graduated with PhD in Cultural Studies in 2010. Assistant Professor, Department of Art History and Communication Studies Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies, McGill University https://www.mcgill.ca/ahcs/people-contacts/faculty/bobby-benedicto Dr Danny Butt Graduated with a PhD in Media and Communications in 2012. Associate Director (Research), Victorian College of the Arts https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person605491 Dr Larissa McLean Davies Graduated with a PhD in English & Theatre Studies in 2007. Associate Professor, Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne https://findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person11095 Dr Marcos Dias Graduated with a PhD in Media and Communications in 2015. Lecturer in Media Studies, University of Maynooth, Ireland https://www.maynoothuniversity.ie/people/marcos-dias Dr Dan Disney Graduated with a PhD in Creative Writing in 2010. Associate Professor in English Literature, Department of English, University of Sogang, South Korea http://sogang.academia.edu/DDisney Dr Lisa Fletcher Graduated with a PhD in English & Theatre studies in 2002. Associate Professor of English and Deputy Head of School of Humanities, University of Tasmania http://www.utas.edu.au/profiles/staff/english/lisa-fletcher Dr Anthony Gardner Graduated with an MA in Art History in 2002. -

Index Journal Issue No2 Law History Decays Into Images

INDEX JOURNAL ISSUE NO2 LAW HISTORY DECAYS INTO IMAGES, NOT INTO STORIES. GUEST EDITED BY DESMOND MANDERSON AND IAN MCLEAN HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.38030/INDEX-JOURNAL.2020.2 INDEX JOURNAL ISSUE NO2 LAW HISTORY DECAYS INTO IMAGES, NOT INTO STORIES. GUEST EDITED BY DESMOND MANDERSON AND IAN MCLEAN HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.38030/INDEX-JOURNAL.2020.2 INDEX JOURNAL ISSUE NO. 2 – LAW Guest Edited by Desmond Manderson & Ian McLean CONTENTS p. 5 EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION by Desmond Manderson & Ian McLean Part 1 – LAWSCAPES p. 17 THE DANCER FROM THE DANCE: Images and Imaginaries by Desmond Manderson p. 39 FIGURING FOLK JUSTICE: Francis Howard Greenway’s Prison Scenes from Newgate, Bristol, 1812 by Helen Hughes p. 61 EMANUEL DE WITTE’S INTERIOR OF THE OUDE KERK, DELFT: Images of Life as Religion, Individualism, and the Critique of Legal Ideology by David S. Caudill p. 81 CLOTHES MAKETH THE MAN: Mimesis, Laughter, and the Colonial Rule of Law by Shane Chalmers Part 2 – LACUNAE p. 105 LAW-LESS SILENCE: Extraordinary Rendition, the Law, and Silence in Edmund Clark’s Negative Publicity by Clare Fuery-Jones p. 127 EARLE’S LITHOGRAPHY AND THE FORCE OF LAW by Keith Broadfoot p. 145 FORENSIC LISTENING IN LAWRENCE ABU HAMDAN’S SAYDNAYA (THE MISSING 19DB) by James Parker Part 3 – ICONS p. 171 NO STICKERS ON HARD-HATS, NO FLAGS ON CRANES: How the Federal Building Code Highlights the Repressive Tendencies of Power by Agatha Court p. 195 SPECTROPOLITICS AND INVISIBILITY OF THE MIGRANT: On Images that Make People “Illegal” by Dorota Gozdecka p. 213 MURALS AS A PLAY ON SPACE IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN by Samuel Blanch 3 INDEX JOURNAL ISSUE NO. -

IPA REVIEW ESTABLISHED in 1947 by CHARLES KEMP, FOUNDING DIRECTOR of the INSTITUTE of PUBLIC AFFAIRS Vol

IPA REVIEW ESTABLISHED IN 1947 BY CHARLES KEMP, FOUNDING DIRECTOR OF THE INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS Vol. 47 No. 1, 1994 7 Unemployment: 58 Economic Knowledge Who or What is to Blame? and the Churches Helen Hughes Malcolm Anderson The search for scapegoats is deflecting Fewer than one in four in the religious media attention from. the real causes. believe that minimum wages keep young people out of jobs. 11 Under Fire Eric Home Issues which the inquiry into Victorian police shootings should consider. 2 Letters 14 A Peacetime Role for the Defence Force 5 From the Editor David Evans The romance of knowledge and power. Finding useful employment for the Australian Defence Force. 16 Moore Economics Des Moore 19 Employee Share Schemes — Much nonsense is being spoken about A Mixed Blessing population. Nick Renton 18 Press Index The benefits are not as great as they first Should the authority of a UN committee be seem. invoked to over-ride Tasmanias anti- homosexual laws? 23 Mabo: A European Perspective 22 Down to Earth Martin Mears Ron Brunton Ancient disputes should be kept buried. New research on the greenhouse effect which the media have ignored. 25 Science, Morals and AIDS 39 Letter from America Lucy Sullivan Harry Gelber Our knowledge of public health is not being applied to A mood of profound ambivalence has settled the fight against AIDS. on the US public. 41 Around the States 31 What Makes Democracy Work? Mike Nahan Robert D. Putnam The Commonwealth Government is Why democratic governments succeed in squeezing out the States. some places and fail in others. -

14. Policy Alchemy and the Magical Transformation of Aboriginal Society

14. Policy Alchemy and the Magical Transformation of Aboriginal Society David F . Martin Anthropos Consulting and The Australian National University Traditional culture has been stultified and degraded so that it has not moved from sorcery to the rule of reason, from polygamy to the equality of women with men and from ‘pay-back’ to the rule of law. — Helen Hughes (2007), Centre for Independent Studies This chapter focuses on an issue to which Nicolas Peterson has directed our attention for nearly two decades (for example, Peterson 1991, 1998, 2005; Peterson and Taylor 2003): that many Aboriginal people, particularly but not only those living in remote regions, bring distinctive repertoires of values, world views and practices to their engagement with the general Australian society that have profound implications for the nature of that engagement. Critical social analysis of the situations of Aboriginal people must never ignore, for example, the historical role of the state; but neither must it avoid the central role of Aboriginal agency. My own research with Wik people living in Aurukun, western Cape York Peninsula (Martin 1993),1 showed how sorcery—or at least, accusations of it—is deeply implicated in the endemic disputation and violence that have become such a dominant feature of contemporary Aurukun life. I argued that Wik retaliation or ‘payback’, whether conducted openly through violence or secretly through sorcery, provides a particular instance of more general principles—those of reciprocity and equivalence—in the transactions of material and symbolic items through which autonomy and relatedness are realised. Like the flows of material goods, the exchanges of retribution serve to structure and reproduce the relationships not only between individuals but between collectivities (such as families). -

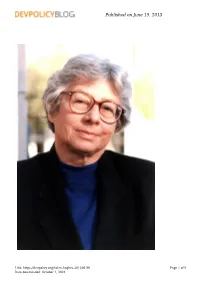

Helen Hughes AO (1 October 1928 – 15 June 2013)

Helen Hughes AO (1 October 1928 – 15 June 2013) A Tribute Published August 2014 by The Centre for Independent Studies Limited PO Box 92, St Leonards, NSW 1590 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cis.org.au Views expressed in the publications of The Centre for Independent Studies are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre’s staff, advisers, directors, or officers. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: Title: Helen Hughes (1 October 1928 - 15 June 2013) : a tribute / Contributors, Greg Lindsay, Tony Abbott, Noel Pearson, Ron Duncan, Glenys Byrne. ISBN: 9781922184320 (paperback) Series: CIS policy forums ; PF26 Subjects: Hughes, Helen, 1928-2013. Economists--Australia. Festschriften. Other Authors/Contributors: Lindsay, Greg, 1949- Abbott, Tony, 1957- Pearson, Noel, 1965- Duncan, Ronald C., 1936- Byrne, Glenys. Centre for Independent Studies (Australia), issuing body. Dewey Number: 330.0994 ©2014 The Centre for Independent Studies Edited by Mangai Pitchai Cover and layout design by Ryan Acosta Helen Hughes AO (1 October 1928 – 15 June 2013) A Tribute Greg Lindsay AO The Hon Tony Abbott MP Noel Pearson Ron Duncan Glenys Byrne CIS Policy Forum 26 2014 Contents Greg Lindsay AO .................................................................... 1 The Hon Tony Abbott MP ....................................................... 3 Noel Pearson .......................................................................... 7 Ron Duncan ........................................................................ -

Peter Mccawley, January 2018

Southeast Asian Studies at ANU – Personal recollection ANU and Asia: A Life between Town and Gown Peter McCawley, January 2018 Beginning Asian Studies It all started in the mid 1960s. I was an economics student at the University of Queensland in Brisbane. In a course on economic development, it soon became clear that there were huge differences in income and wealth between rich and poor countries. Our text was one of the earliest books on economic development, Economic Development: Problems, Principles and Policies, by Benjamin Higgins. Higgins, a Canadian, later settled in Canberra. Towards the end of his life he was active in the National Centre for Development Studies at ANU.1 I was worried by these huge gaps between rich and poor countries. They seemed to me then – as they still seem to me now – a key global issue. Moreover, for many of my generation the North‐South gap in Asia was brought into sharp relief by the war in Vietnam. In Australia, the national involvement in the Vietnam War took hold in 1965. In a dramatic declaration, in May 1965 in Parliament, the parliamentary Labor Party declared itself opposed to the war. The previous year, conscription had been introduced to support the war effort. These events deeply divided Australian society and affected attitudes toward Asia for the next several decades. The war in Vietnam notwithstanding, rapid political and social changes were occurring in Asia in places such as China, South Asia, and Indonesia. In 1965 and 1966, dramatic political events were taking place as Soeharto’s “New Order” government seemed to be succeeding in sidelining Sukarno and introducing a major realignment in the geopolitical balance of power in Southeast Asia. -

July 2013 Newsletter

JULY 2013 NEWSLETTER IN Helen Hughes remembered THIS NSW Branch AGM ISSUE LinkedIn NSW Branch Members Group Australian Conference of Economists 7-10 July in Perth Seminar 17th July Dr Peter Abelson, Economics of Local Government Dear members, We begin this newsletter with some sad news. Helen Hughes, AO, Distinguished Fellow of the Economic Society, and an inspiration to many of us, passed away on 15th June. She will be greatly missed. In this newsletter, NSW Branch member, Professor John Lodewijks has provided a brief reflection on this truly remarkable person. Also earlier this month – on 19th June – we held the 2013 annual general meeting (AGM) of the NSW Branch of the Economic Society. At the AGM the office bearers and council members for 2013/14 were appointed. It’s pleasing that we have a healthy mix of returning members and new council members. On behalf of the society I’d like to thank the outgoing Secretary, Ellis Connolly, and council member Isaac Gross who have each done so much for the society over the last few years. There are a few events of note coming up. Early in July (7-10 July), the Economic Society of Australia’s premier event, the Australian Conference of Economists (ACE2013), will be held in Perth. This newsletter contains additional details; better still go to the ACE2013 website (http://www.ace2013.org.au). We’re delighted that the NSW Branch monthly seminar program is kicking off this financial year on 17th July with a talk by Professor Peter Abelson, Mayor of Mosman on the economics of local government. -

Helen Hughes

Devpolicy Blog from the Development Policy Centre Australian aid | PNG and the Pacific | Global development policy http://www.devpolicy.org Helen Hughes Author : Maree Tait Date : June 19, 2013 Helen came to The Australian National University in 1983, a whirlwind of ideas and action. She was on a mission to create the university’s first graduate school and to anchor it in the economics of development with a primary focus on the Asia Pacific region, and with a strong contingent of overseas students. I met her then. Initially the university was not impressed - not about the idea of a new graduate school, nor about a large number of overseas students. Today the Crawford School of Public Policy at ANU stands as testimony to Helen’s pioneering efforts and her innovative mind. She had a torrid time dealing with the Chancelry. I remember our National Centre for Development Studies Advisory meetings as sweaty affairs. Interestingly, given Helen’s aid fatigue in her later years, the Crawford School today stands as one of the major successes of the Australian aid program. Some 600 students from developing countries are pursuing diploma, master and PhD studies, and the school can count prime ministers, ministers of government, business leaders and many public sector leaders in neighbouring countries as alumni. Nowadays many students pay for their own training, but in the early days they all owed their scholarships to Helen’s successful wooing of the head of AusAID, Bob Dunn. She could get her own way. Helen took her students seriously. ‘If it was not for the students’, she would say when tired by administration. -

Helen Hughes

Published on June 19, 2013 Link: https://devpolicy.org/helen-hughes-20130619/ Page 1 of 5 Date downloaded: October 1, 2021 Published on June 19, 2013 Helen Hughes By Maree Tait Helen came to The Australian National University in 1983, a whirlwind of ideas and action. She was on a mission to create the university’s first graduate school and to anchor it in the economics of development with a primary focus on the Asia Pacific region, and with a strong contingent of overseas students. I met her then. Initially the university was not impressed – not about the idea of a new graduate school, nor about a large number of overseas students. Today the Crawford School of Public Policy at ANU stands as testimony to Helen’s pioneering efforts and her innovative mind. She had a torrid time dealing with the Chancelry. I remember our National Centre for Development Studies Advisory meetings as sweaty affairs. Interestingly, given Helen’s aid fatigue in her later years, the Crawford School today stands as one of the major successes of the Australian aid program. Some 600 students from developing countries are pursuing diploma, master and PhD studies, and the school can count prime ministers, ministers of government, business leaders and many public sector leaders in neighbouring countries as alumni. Nowadays many students pay for their own training, but in the early days they all owed their scholarships to Helen’s successful wooing of the head of AusAID, Bob Dunn. She could get her own way. Helen took her students seriously. ‘If it was not for the students’, she would say when tired by administration. -

ANZRSAI Newsletter

ANZRSAI Newsletter An interdisciplinary international association of researchers and practitioners on the growth and development of urban, regional and international systems July 2010 REGIONAL RESEARCH Technology and industrial agglomeration: Papers in Regional Science 1 Evidence from computer usage Adapting to Water Scarcity 2 Christopher H. Wheeler Research division, Federal Reserve Bank of St. REGIONS & PRACTICE Louis, PO Box 442, St. Louis, MO 63166, USA Ready for Tomorrow: Regional (e-mail: [email protected]) Development Victoria Blueprint 2 What went before? 2 Identifying urbanisation and localisation How RfT was Developed 3 externalities in manufacturing and service Australian Bureau of Statistics industries National Regional Profiles 4 Daniel J Graham Centre for Transport Studies, Imperial College Australian Statistical Geography 4 London, London SW7 2AZ, UK (e-mail: Australian Federal Budget 2010-11 4 [email protected]) Thanks to The Cockatoo 6 Helen Hughes on Pacific Aid 6 Maximising coverage of spatial demand for service UPCOMING CONFERENCES 6 Daoqin Tong1, Alan T. Murray2 1 Department of Geography and Regional SCHOLARSHIPS 8 Development, The University of Arizona, 408 Harvill Building, Box #2, ABOUT ANZRSAI 1103 East 2nd Street, Tucson, AZ 85721 USA (e- Professor Bob Stimson RSAI Fellow 9 mail: [email protected]) Professor Rolf Gerritsen Councillor 9 2 Department of Geographical Sciences, Arizona ANZRSAI Council Notes 10 State University, Tempe, AZ 85287, USA ANZRSAI Council 2009-10 10 (e-mail: [email protected]) ANZRSAI Annual Conference: Road investment and regional productivity Second Call for Papers 11 growth: the effects of vehicle intensity and congestion Daniel Montolio, Albert Solé-Ollé REGIONAL RESEARCH Departament d‟Hisenda Pública, Universitat de Barcelona, Institut d‟Economia di Barcelona (IEB), Av. -

15Th International First Year in Higher Education Conference

THE INTERNATIONAL FIRST YEAR IN HIGHER EDUCATION CONFERENCE NEW HORIZONS Sofitel Brisbane Central www.fyhe.com.au ISBN: 978-1-921897-39-9 | CRICOS No. 00213J Publishing details Editor: Rachel Mortimer, Events Manager, QUT Events Publisher: QUT Events Conference papers Please visit our HERD: E1 Conference papers (http://www.research.qut.edu.au/data/pubcollections/herdc/e1-conference-paper.jsp) information page. To open paper, click on the relevant ‘Paper’ FYHE CONFERENCE 2012 Program Wednesday 27 June 2012 8:00am Registration Opens 8:45am - 9:00am Welcome to Country & Conference Opening Official opening of conference and introduction of Prof Liz Thomas Professor Peter Coaldrake – Vice Chancellor, Queensland University of Technology Keynote Session 1 9:00am - 10:00am What works? Facilitating an effective transition into higher education. Professor Liz Thomas 10:00am - 10:50am Morning Tea including Poster Session Parallel Session 1 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E 1F 1G 11:00am - 11:30am University Language Learners- Meeting the needs of First Beyond FYHE 2020: Imagining You can lead a horse to water... Waiting for the crisis Does peer learning work for Building on solid bedrock: Perceptions of the Transition Year students ‘At Risk’: Success the Future of First Year Higher Can we make them drink? everyone? The impact of peer Embedding language from School to University of the Academic Success Education Strategies for encouraging learning on different student development in first-year Program students to take responsibility groups geology curriculum for task