An ALMA Archival Exploitation of Herbig Group I and II Protoplanetary Disks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plasma Physics and Pulsars

Plasma Physics and Pulsars On the evolution of compact o bjects and plasma physics in weak and strong gravitational and electromagnetic fields by Anouk Ehreiser supervised by Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia as part of an internship at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy, Bonn March 2010 2 This composition was written as part of two internships at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy in April 2009 at the Radiotelescope in Effelsberg and in February/March 2010 at the Institute in Bonn. I am very grateful for the support, expertise and patience of Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia, who supervised my internship and introduced me to the basic concepts and the current research in the field. Contents I. Life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure 2. Gravitational collapse and supernova 3. Star remnants II. Properties of Compact Objects 1. White Dwarfs 2. Neutron Stars 3. Black Holes 4. Hypothetical Quark Stars 5. Relativistic Effects III. Plasma Physics 1. Essentials 2. Single Particle Motion in a magnetic field 3. Interaction of plasma flows with magnetic fields – the aurora as an example IV. Pulsars 1. The Discovery of Pulsars 2. Basic Features of Pulsar Signals 3. Theoretical models for the Pulsar Magnetosphere and Emission Mechanism 4. Towards a Dynamical Model of Pulsar Electrodynamics References 3 Plasma Physics and Pulsars I. The life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure Stars are formed in molecular clouds in the interstellar medium, which consist mostly of molecular hydrogen (primordial elements made a few minutes after the beginning of the universe) and dust. -

XIII Publications, Presentations

XIII Publications, Presentations 1. Refereed Publications E., Kawamura, A., Nguyen Luong, Q., Sanhueza, P., Kurono, Y.: 2015, The 2014 ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: First Results from Aasi, J., et al. including Fujimoto, M.-K., Hayama, K., Kawamura, High Angular Resolution Observations toward the HL Tau Region, S., Mori, T., Nishida, E., Nishizawa, A.: 2015, Characterization of ApJ, 808, L3. the LIGO detectors during their sixth science run, Classical Quantum ALMA Partnership, et al. including Asaki, Y., Hirota, A., Nakanishi, Gravity, 32, 115012. K., Espada, D., Kameno, S., Sawada, T., Takahashi, S., Ao, Y., Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific Hatsukade, B., Matsuda, Y., Iono, D., Kurono, Y.: 2015, The 2014 Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, Astrophysical Implications ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: Observations of the Strongly of the Binary Black Hole Merger GW150914, ApJ, 818, L22. Lensed Submillimeter Galaxy HATLAS J090311.6+003906 at z = Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific 3.042, ApJ, 808, L4. Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, Observation of ALMA Partnership, et al. including Asaki, Y., Hirota, A., Nakanishi, Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger, Phys. Rev. K., Espada, D., Kameno, S., Sawada, T., Takahashi, S., Kurono, Lett., 116, 061102. Y., Tatematsu, K.: 2015, The 2014 ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific Observations of Asteroid 3 Juno at 60 Kilometer Resolution, ApJ, Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, GW150914: Implications 808, L2. for the Stochastic Gravitational-Wave Background from Binary Black Alonso-Herrero, A., et al. including Imanishi, M.: 2016, A mid-infrared Holes, Phys. -

Exors and the Stellar Birthline Mackenzie S

A&A 600, A133 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201630196 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics EXors and the stellar birthline Mackenzie S. L. Moody1 and Steven W. Stahler2 1 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomy Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 6 December 2016 / Accepted 23 February 2017 ABSTRACT We assess the evolutionary status of EXors. These low-mass, pre-main-sequence stars repeatedly undergo sharp luminosity increases, each a year or so in duration. We place into the HR diagram all EXors that have documented quiescent luminosities and effective temperatures, and thus determine their masses and ages. Two alternate sets of pre-main-sequence tracks are used, and yield similar results. Roughly half of EXors are embedded objects, i.e., they appear observationally as Class I or flat-spectrum infrared sources. We find that these are relatively young and are located close to the stellar birthline in the HR diagram. Optically visible EXors, on the other hand, are situated well below the birthline. They have ages of several Myr, typical of classical T Tauri stars. Judging from the limited data at hand, we find no evidence that binarity companions trigger EXor eruptions; this issue merits further investigation. We draw several general conclusions. First, repetitive luminosity outbursts do not occur in all pre-main-sequence stars, and are not in themselves a sign of extreme youth. They persist, along with other signs of activity, in a relatively small subset of these objects. -

The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459

Whitworth et al.: The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459 The Formation of Brown Dwarfs: Theory Anthony Whitworth Cardiff University Matthew R. Bate University of Exeter Åke Nordlund University of Copenhagen Bo Reipurth University of Hawaii Hans Zinnecker Astrophysikalisches Institut, Potsdam We review five mechanisms for forming brown dwarfs: (1) turbulent fragmentation of molec- ular clouds, producing very-low-mass prestellar cores by shock compression; (2) collapse and fragmentation of more massive prestellar cores; (3) disk fragmentation; (4) premature ejection of protostellar embryos from their natal cores; and (5) photoerosion of pre-existing cores over- run by HII regions. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. Their relative importance probably depends on environment, and should be judged by their ability to reproduce the brown dwarf IMF, the distribution and kinematics of newly formed brown dwarfs, the binary statis- tics of brown dwarfs, the ability of brown dwarfs to retain disks, and hence their ability to sustain accretion and outflows. This will require more sophisticated numerical modeling than is presently possible, in particular more realistic initial conditions and more realistic treatments of radiation transport, angular momentum transport, and magnetic fields. We discuss the mini- mum mass for brown dwarfs, and how brown dwarfs should be distinguished from planets. 1. INTRODUCTION form a smooth continuum with those of low-mass H-burn- ing stars. Understanding how brown dwarfs form is there- The existence of brown dwarfs was first proposed on the- fore the key to understanding what determines the minimum oretical grounds by Kumar (1963) and Hayashi and Nakano mass for star formation. In section 3 we review the basic (1963). -

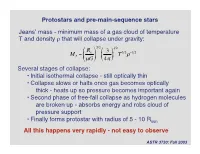

Protostars and Pre-Main-Sequence Stars Jeans' Mass

Protostars and pre-main-sequence stars Jeans’ mass - minimum mass of a gas cloud of temperature T and density r that will collapse under gravity: 3 2 1 2 Ê Rg ˆ Ê 3 ˆ 3 2 -1 2 MJ = Á ˜ Á ˜ T r Ë mG¯ Ë 4p ¯ Several stages of collapse: • Initial isothermal collapse - still optically thin • Collapse† slows or halts once gas becomes optically thick - heats up so pressure becomes important again • Second phase of free-fall collapse as hydrogen molecules are broken up - absorbs energy and robs cloud of pressure support • Finally forms protostar with radius of 5 - 10 Rsun All this happens very rapidly - not easy to observe ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Observationally, classify young stellar objects (YSOs) by looking at their spectral energy distributions (SEDs). Four main classes of object have been identified: flux Class 0 source wavelength in microns 1 10 100 (10-6 m) Observationally, this is a source whose SED peaks in the far-infrared or mm part of the spectrum. No flux in the near-infrared (at a few microns). Effective temperature is several 10s of degrees Kelvin. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 What are Class 0 sources? • Still very cool - not much hotter than molecular cloud cores. Implies extreme youth. • Deeply embedded in gas and dust, any shorter wavelength radiation is absorbed and reradiated at longer wavelengths before escaping. • Fairly small numbers - consistent with short duration of the initial collapse. • Outflows are seen - suggests a protostar is forming. Earliest observed stage of star formation… ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Class 1 flux Very large infrared excess Protostellar black body emission wavelength in microns 1 10 100 (10-6 m) Class 1 sources also have SEDs that rise into the mid and far infrared. -

New Mid-Infrared Imaging Constraints on Companions and Protoplanetary Disks Around Six Young Stars? D

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. main ©ESO 2021 February 26, 2021 New mid-infrared imaging constraints on companions and protoplanetary disks around six young stars? D. J. M. Petit dit de la Roche1, N. Oberg2, M. E. van den Ancker1, I. Kamp2, R. van Boekel3, D. Fedele4, V. D. Ivanov1, M. Kasper1, H. U. Käufl1, M. Kissler-Patig5, P. A. Miles-Páez1, E. Pantin6, S. P. Quanz7, Ch. Rab2; 8, R. Siebenmorgen1, and L. B. F. M. Waters9; 10 1 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 2, 85748 Garching, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, P.O. Box 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands 3 Max-Planck Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 4 INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy 5 European Space Agency, Camino Bajo del Castillo, s/n., Urb. Villafranca del Castillo, 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 6 CEA, IRFU, DAp, AIM, Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, CNRS, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 7 Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics, ETH Zurich, Wolfgang-Pauli-Strasse 27, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland 8 Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstrasse 1, 85748 Garching, Germany 9 Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University Nijmegen, P.O.Box 9010, 6500 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands 10 SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Sorbonnelaan 2, 3584 CA Utrecht, The Netherlands Received XXXX; accepted XXXX ABSTRACT Context. Mid-infrared (mid-IR) imaging traces the sub-micron and micron-sized dust grains in protoplanetary disks and it offers constraints on the geometrical properties of the disks and potential companions, particularly if those companions have circumplanetary disks. -

Star Formation in the “Gulf of Mexico”

A&A 528, A125 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200912671 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Star formation in the “Gulf of Mexico” T. Armond1,, B. Reipurth2,J.Bally3, and C. Aspin2, 1 SOAR Telescope, Casilla 603, La Serena, Chile e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 640 N. Aohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720, USA e-mail: [reipurth;caa]@ifa.hawaii.edu 3 Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 9 June 2009 / Accepted 6 February 2011 ABSTRACT We present an optical/infrared study of the dense molecular cloud, L935, dubbed “The Gulf of Mexico”, which separates the North America and the Pelican nebulae, and we demonstrate that this area is a very active star forming region. A wide-field imaging study with interference filters has revealed 35 new Herbig-Haro objects in the Gulf of Mexico. A grism survey has identified 41 Hα emission- line stars, 30 of them new. A small cluster of partly embedded pre-main sequence stars is located around the known LkHα 185-189 group of stars, which includes the recently erupting FUor HBC 722. Key words. Herbig-Haro objects – stars: formation 1. Introduction In a grism survey of the W80 region, Herbig (1958) detected a population of Hα emission-line stars, LkHα 131–195, mostly The North America nebula (NGC 7000) and the adjacent Pelican T Tauri stars, including the little group LkHα 185 to 189 located nebula (IC 5070), both well known for the characteristic shapes within the dark lane of the Gulf of Mexico, thus demonstrating that have given rise to their names, are part of the single large that low-mass star formation has recently taken place here. -

![Arxiv:1101.3707V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 19 Jan 2011 E Eg,Cretre L 09 Ee 09.Tesignature the Pro 2009)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0458/arxiv-1101-3707v1-astro-ph-sr-19-jan-2011-e-eg-cretre-l-09-ee-09-tesignature-the-pro-2009-950458.webp)

Arxiv:1101.3707V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 19 Jan 2011 E Eg,Cretre L 09 Ee 09.Tesignature the Pro 2009)

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. 15622 c ESO 2011 January 20, 2011 Searching for gas emission lines in Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph (IRS) spectra of young stars in Taurus Baldovin-Saavedra, C.1,2, Audard, M.1,2, G¨udel, M.3, Rebull, L. M.4, Padgett, D. L.4, Skinner, S. L.5, Carmona, A.1,2, Glauser, A. M.6,7, and Fajardo-Acosta, S. B.8 1 ISDC Data Centre for Astrophysics, Universit´ede Gen`eve, 16 Chemin d’Ecogia, CH-1290 Versoix, Switzerland 2 Observatoire Astronomique de l’Universit´ede Gen`eve, 51 Chemin de Maillettes, CH-1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 3 University of Vienna, Department of Astronomy, T¨urkenschanzstrasse 17, A-1180 Vienna, Austria 4 Spitzer Science Center, California Institute of Technology, 220-6 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91125 USA 5 Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0389, USA 6 ETH Z¨urich, 27 Wolfgang-Pauli-Str., CH-8093 Z¨urich, Switzerland 7 UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, EH3 9HJ Edinburgh, UK 8 IPAC, California Institute of Technology, 770 South Wilson Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA Received August 2010; accepted January 2011 ABSTRACT Context. Our knowledge of circumstellar disks has traditionally been based on studies of dust. However, gas dominates the disk mass and its study is key to our understanding of accretion, outflows, and ultimately planet formation. The Spitzer Space Telescope provides access to gas emission lines in the mid-infrared, providing crucial new diagnostics of the physical conditions in accretion disks and outflows. Aims. We seek to identify gas emission lines in mid-infrared spectra of 64 pre-main-sequence stars in Taurus. -

Searching for Gas Emission Lines in Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph \(IRS

A&A 528, A22 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201015622 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Searching for gas emission lines in Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph (IRS) spectra of young stars in Taurus C. Baldovin-Saavedra1,2, M. Audard1,2, M. Güdel3,L.M.Rebull4,D.L.Padgett4, S. L. Skinner5, A. Carmona1,2,A.M.Glauser6,7, and S. B. Fajardo-Acosta8 1 ISDC Data Centre for Astrophysics, Université de Genève, 16 chemin d’Ecogia, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] 2 Observatoire Astronomique de l’Université de Genève, 51 chemin de Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 3 University of Vienna, Department of Astronomy, Türkenschanzstrasse 17, 1180 Vienna, Austria 4 Spitzer Science Center, California Institute of Technology, 220-6 1200 East California Boulevard, CA 91125 Pasadena, USA 5 Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy, University of Colorado, CO 80309-0389 Boulder, USA 6 ETH Zürich, 27 Wolfgang-Pauli-Str., 8093 Zürich, Switzerland 7 UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, EH3 9HJ Edinburgh, UK 8 IPAC, California Institute of Technology, 770 South Wilson Avenue, CA 91125 Pasadena, USA Received 19 August 2010 / Accepted 14 January 2011 ABSTRACT Context. Our knowledge of circumstellar disks has traditionally been based on studies of dust. However, gas dominates the disk mass and its study is key to our understanding of accretion, outflows, and ultimately planet formation. The Spitzer Space Telescope provides access to gas emission lines in the mid-infrared, providing crucial new diagnostics of the physical conditions in accretion disks and outflows. Aims. We seek to identify gas emission lines in mid-infrared spectra of 64 pre-main-sequence stars in Taurus. -

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy Special Publications No. 1 George Herbig in 1960 —————————————————————– GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution —————————————————————– Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 640 North Aohoku Place Hilo, HI 96720 USA . Dedicated to Hannelore Herbig c 2016 by Bo Reipurth Version 1.0 – April 19, 2016 Cover Image: The HH 24 complex in the Lynds 1630 cloud in Orion was discov- ered by Herbig and Kuhi in 1963. This near-infrared HST image shows several collimated Herbig-Haro jets emanating from an embedded multiple system of T Tauri stars. Courtesy Space Telescope Science Institute. This book can be referenced as follows: Reipurth, B. 2016, http://ifa.hawaii.edu/SP1 i FOREWORD I first learned about George Herbig’s work when I was a teenager. I grew up in Denmark in the 1950s, a time when Europe was healing the wounds after the ravages of the Second World War. Already at the age of 7 I had fallen in love with astronomy, but information was very hard to come by in those days, so I scraped together what I could, mainly relying on the local library. At some point I was introduced to the magazine Sky and Telescope, and soon invested my pocket money in a subscription. Every month I would sit at our dining room table with a dictionary and work my way through the latest issue. In one issue I read about Herbig-Haro objects, and I was completely mesmerized that these objects could be signposts of the formation of stars, and I dreamt about some day being able to contribute to this field of study. -

Searching for Gas Emission Lines in Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph (IRS

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. 15622 c ESO 2018 February 7, 2018 Searching for gas emission lines in Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph (IRS) spectra of young stars in Taurus Baldovin-Saavedra, C.1,2, Audard, M.1,2, G¨udel, M.3, Rebull, L. M.4, Padgett, D. L.4, Skinner, S. L.5, Carmona, A.1,2, Glauser, A. M.6,7, and Fajardo-Acosta, S. B.8 1 ISDC Data Centre for Astrophysics, Universit´ede Gen`eve, 16 Chemin d’Ecogia, CH-1290 Versoix, Switzerland 2 Observatoire Astronomique de l’Universit´ede Gen`eve, 51 Chemin de Maillettes, CH-1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 3 University of Vienna, Department of Astronomy, T¨urkenschanzstrasse 17, A-1180 Vienna, Austria 4 Spitzer Science Center, California Institute of Technology, 220-6 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91125 USA 5 Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0389, USA 6 ETH Z¨urich, 27 Wolfgang-Pauli-Str., CH-8093 Z¨urich, Switzerland 7 UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, EH3 9HJ Edinburgh, UK 8 IPAC, California Institute of Technology, 770 South Wilson Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA Received August 2010; accepted January 2011 ABSTRACT Context. Our knowledge of circumstellar disks has traditionally been based on studies of dust. However, gas dominates the disk mass and its study is key to our understanding of accretion, outflows, and ultimately planet formation. The Spitzer Space Telescope provides access to gas emission lines in the mid-infrared, providing crucial new diagnostics of the physical conditions in accretion disks and outflows. Aims. We seek to identify gas emission lines in mid-infrared spectra of 64 pre-main-sequence stars in Taurus. -

A Study of Herbig Ae Be Star HD 163296: Variability in CO and OH Diana Lyn Hubis Yoder Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2016 A Study of Herbig Ae Be Star HD 163296: Variability in CO and OH Diana Lyn Hubis Yoder Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Hubis Yoder, Diana Lyn, "A Study of Herbig Ae Be Star HD 163296: Variability in CO and OH" (2016). All Theses. 2348. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2348 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study of Herbig Ae Be Star HD 163296 Variability in CO and OH A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Physics and Astronomy by Diana Lyn Hubis Yoder May 2016 Accepted by: Dr. Sean Brittain, Committee Chair Dr. Mark Leising Dr. Jeremy King Dr. Chad Sosolik Abstract Spectra of the Herbig Ae Be star HD 163296 show variability in the CO and OH ro-vibrational emission lines. Documented here is the variance of OH emission lines between measurements separated by a period of three years. By comparing this variability to the variability of CO, we aim to determine whether the two are linked through an event such as disk winds. We find the profiles of OH and CO taken within three months of each other to have exceedingly similar profile shapes. However, the variability seen between the OH data sets needs further work to verify whether the changes we see are reproducible.