Michelle Akers Thori Staples Bryan Cindy Parlow Cone Stephanie Cox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019Collegealmanac 8-13-19.Pdf

college soccer almanac Table of Contents Intercollegiate Coaching Records .............................................................................................................................2-5 Intercollegiate Soccer Association of America (ISAA) .......................................................................................6 United Soccer Coaches Rankings Program ...........................................................................................................7 Bill Jeffrey Award...........................................................................................................................................................8-9 United Soccer Coaches Staffs of the Year ..............................................................................................................10-12 United Soccer Coaches Players of the Year ...........................................................................................................13-16 All-Time Team Academic Award Winners ..............................................................................................................17-27 All-Time College Championship Results .................................................................................................................28-30 Intercollegiate Athletic Conferences/Allied Organizations ...............................................................................32-35 All-Time United Soccer Coaches All-Americas .....................................................................................................36-85 -

The Academic and Behavioral Impact of Multiple Sport Participation on High School Athletes

Lindenwood University Digital Commons@Lindenwood University Dissertations Theses & Dissertations Fall 10-2017 The Academic and Behavioral Impact of Multiple Sport Participation on High School Athletes Christopher James Kohl Lindenwood University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons Recommended Citation Kohl, Christopher James, "The Academic and Behavioral Impact of Multiple Sport Participation on High School Athletes" (2017). Dissertations. 199. https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/dissertations/199 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses & Dissertations at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Academic and Behavioral Impact of Multiple Sport Participation on High School Athletes by Christopher James Kohl October, 2017 A Dissertation submitted to the Education Faculty of Lindenwood University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education School of Education Acknowledgements I would like to thank my wife, Ashley, for her loving support through this process. I would also like to thank my children, Adam and Grace, for being patient with Daddy while he “works on his paper.” My appreciation goes to Dr. Hanson, Dr. Henderson, and my committee for all of the guidance and direction they provided through this adventure. The inspiration for this work was fueled by all of the student athletes I have seen who should have been encouraged to participate in multiple sports and by my grandfather, Joseph Edward, who always encouraged me to do my best. -

2014 Women's Soccer Guide.Indd Sec1:87 10/17/2014 12:43:12 PM Bbuffsuffs Inin Thethe Leagueleague

BBuffsuffs InIn thethe LeagueLeague Th e National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) is the top level professional women’s soccer league in the United States. It began play in spring 2013 with eight teams: Boston Breakers, Chicago Red Stars, FC Kansas City, Portland Th orns FC, Seattle Reign FC, Sky Blue FC, the Washington Spirit and the Western New York Flash. Th e Houston Dash joined the league in 2014. Based in Chicago, the NWSL is supported by the United States Soccer Federation, Canadian Soccer Association and Federation of Mexican Football. Each of the league’s nine clubs will play a total of 24 games during a 19-week span, with the schedule beginning the weekend of April 12-13 and concluding the weekend of Aug. 16-17. Th e top four teams will qualify for the NWSL playoff s and compete in the semifi nals on Aug. 23-24. Th e NWSL will crown its inaugural champion aft er the fi nal on Sunday, Aug. 31. Nikki Marshall (2006-09): Defender, Portland Th orns FC At Colorado: Holds 20 program records ... Th e all-time leading scorer with 42 goals ... Leads the program with 93 points, 18 game-winning goals and 261 shots attempted ... Set class records as a freshman and sophomore with 17 and nine goals, respectively ... Scored the fastest regulation and overtime goals in CU history, taking less than 30 seconds to score against St. Mary’s College in 2009 (8-1) and against Oklahoma in 2007 (2-1, OT) ... Ranks in the top 10 in 32 other career, season and single game categories .. -

2002 NCAA Soccer Records Book

Division I Women’s Records Individual Records .............................................. 194 Team Records ..................................................... 200 Polls ................................................................... 204 194 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS GOALS PER GAME Career Individual Records Season 704—Beth Zack, Marist, 1995-98 (66 games) 1.76—Lisa Cole, Southern Methodist, 1987 (37 in 21 Official NCAA Division I women’s soccer games) SAVES PER GAME records began with the 1982 season and are Career (Min. 40 goals) Season based on information submitted to the NCAA 1.49—Kelly Smith, Seton Hall, 1997-99 (76 in 51 24.1—Chantae Hendrix, Robert Morris, 1992 (241 in statistics service by institutions participating in games) 10 games) the statistics rankings. Career records of players ASSISTS Career include only those years in which they compet- Game 18.25—Dayna Dicesare, Robert Morris, 1993-96 ed in Division I. Annual champions started in 6—Marit Foss, Jacksonville vs. Alabama A&M, Sept. 1, (657 in 36 games) 2000; Anne-Marie Lapalme, Mercer vs. South the 1998 season, which was the first year the GOALS AGAINST AVERAGE NCAA compiled weekly leaders. In statistical Carolina St., Aug. 27, 2000; Holly Manthei, Notre Dame vs. Villanova, Nov. 3, 1996; Colleen Season (Min. 1,200 minutes) rankings, the rounding of percentages and/or McMahon, Cincinnati vs. Mt. St. Joseph, Sept. 20, 0.05—Anne Sherow, North Carolina, 1987 (1 GA in averages may indicate ties where none exist. In 1982 1,712 min.) these cases, the numerical order of the rankings Season Career (Min. 2,500 minutes) is accurate. 44—Holly Manthei, Notre Dame, 1996 (26 games) 0.14—Anne Sherow, North Carolina, 1985-88 (4 GA Career in 2,525 min.) 129—Holly Manthei, Notre Dame, 1994-97 (100 Scoring games) GOALKEEPER MINUTES PLAYED ASSISTS PER GAME 8,853:12—Emily Oleksiuk, Penn St., 1998-01 POINTS Season Game 1.69—Holly Manthei, Notre Dame, 1996 (44 in 26 Miscellaneous 16—Kristen Arnott, St. -

2020 UNC Women's Soccer Record Book

2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book 1 2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book Carolina Quick Facts Location: Chapel Hill, N.C. 2020 UNC Soccer Media Guide Table of Contents Table of Contents, Quick Facts........................................................................ 2 Established: December 11, 1789 (UNC is the oldest public university in the United States) 2019 Roster, Pronunciation Guide................................................................... 3 2020 Schedule................................................................................................. 4 Enrollment: 18,814 undergraduates, 11,097 graduate and professional 2019 Team Statistics & Results ....................................................................5-7 students, 29,911 total enrollment Misc. Statistics ................................................................................................. 8 Dr. Kevin Guskiewicz Chancellor: Losses, Ties, and Comeback Wins ................................................................. 9 Bubba Cunningham Director of Athletics: All-Time Honor Roll ..................................................................................10-19 Larry Gallo (primary), Korie Sawyer Women’s Soccer Administrators: Year-By-Year Results ...............................................................................18-21 Rich (secondary) Series History ...........................................................................................23-27 Senior Woman Administrator: Marielle vanGelder Single Game Superlatives ........................................................................28-29 -

1985 NSCAA New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Cedarville College

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Men's Soccer Programs Men's Soccer Fall 1985 1985 NSCAA New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ mens_soccer_programs Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons This Program is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Men's Soccer Programs by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1985 NSCAA/New Balance All-America Awards Banquet National Soccer Coaches Association of America Saturday, January 18, 1986 Sheraton - St. Louis Hotel St. Louis, Missouri Dear All-America Performer, Congratulations on being selected as a recipient of the National Soccer Coaches Association of America/New Balance All-America Award for 1985. Your selection as one of the top performers in the Gnited States is a tribute to your hard work, sportsmanship and dedication to the sport of soccer. All of us at New Balance are proud to be associated with the All-America Awards and look forward to presenting each of you with a separate award for your accomplishment. Good luck in your future endeavors and enjoy your stay in St. Louis. Sincerely, James S. Davis President new balance8 EXCLUSIVE SPONSOR OF THE NSCAA/NEW BALANCE ALL-AMERICA AWARDS Program NSCAA/New Balance All-America Awards Banquet Master of Cerem onies............................. William T. Holleman, Second Vice-President, NSCAA The Lovett School, Georgia Invocation.................................... ....................................................................... Whitney Burnham Dartmouth College NSCAA All-America Awards Youth Girl’s and Boy’s T ea m s............................................................................. -

1998 NCAA Champions •20 NCAA Championship Appearances 14-Time SEC Champions ▪1996, ’97, ’98, ’99, ’00, ’01, ’06, ’07, ’08, ’09, ’10, ’12, ’13, ‘15

1998 NCAA Champions •20 NCAA Championship Appearances 14-time SEC Champions ▪1996, ’97, ’98, ’99, ’00, ’01, ’06, ’07, ’08, ’09, ’10, ’12, ’13, ‘15 Today’s Match: What’s Happening? Florida (7-9-4, 4-4-2 SEC) versus Arkansas (12-4-3, 6-3-1 SEC) Two teams meet again in the span of a week Thursday when the Gators face Arkansas in 2018 Date & Time: Thursday, Nov. 1 at 4:30 p.m. ET Southeastern Conference Tournament semifinal play. Site: Orange Beach Sportsplex (1,500) The Coaches: Becky Burleigh, 29th season overall (496-142-42) Florida has advanced to the SEC Tournament each year of the program’s history, winning 12 titles and 24th season at UF (414-119-36/UF), Colby Hale, seventh including the 2015 and 2016 crowns. This is the sixth time the two teams play in SEC Tournament season overall and at Arkansas (70-56-15) action and the first semifinal meeting. The two teams last met during tournament play in the 2016 final, Series Record: UF leads 22-1 with UF taking a 2-1 overtime win. Television: SEC Network Radio: ESPN Gainesville 98.1 FM / 850 AM When the two teams met last Thursday in Gainesville for the regular-season finale, Florida took a 3-0 th Streaming video: SEC Network win over Arkansas. Senior Briana Solis gave UF an early lead with a 20-yard strike in the 10 minute. Internet: live stats and audio for UF vs. Arkansas match available Deanne Rose hit her first two goals of 2018 within a four-minute second-half span to give her four double goal matches in her two seasons as a Gator. -

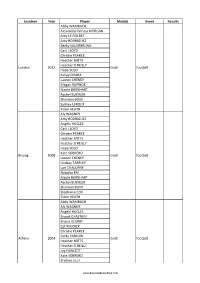

List of All Olympics Prize Winners in Football in U.S.A

Location Year Player Medals Event Results Abby WAMBACH Alexandra Patricia MORGAN Amy LE PEILBET Amy RODRIGUEZ Becky SAUERBRUNN Carli LLOYD Christie PEARCE Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY London 2012 Gold football Hope SOLO Kelley OHARA Lauren CHENEY Megan RAPINOE Nicole BARNHART Rachel BUEHLER Shannon BOXX Sydney LEROUX Tobin HEATH Aly WAGNER Amy RODRIGUEZ Angela HUCLES Carli LLOYD Christie PEARCE Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY Hope SOLO Kate SOBRERO Beijing 2008 Gold football Lauren CHENEY Lindsay TARPLEY Lori CHALUPNY Natasha KAI Nicole BARNHART Rachel BUEHLER Shannon BOXX Stephanie COX Tobin HEATH Abby WAMBACH Aly WAGNER Angela HUCLES Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Cat REDDICK Christie PEARCE Cindy PARLOW Athens 2004 Gold football Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY Joy FAWCETT Kate SOBRERO Kristine LILLY www.downloadexcelfiles.com Lindsay TARPLEY Mia HAMM Shannon BOXX Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Carla OVERBECK Christie PEARCE Cindy PARLOW Danielle SLATON Joy FAWCETT Julie FOUDY Kate SOBRERO Sydney 2000 Silver football Kristine LILLY Lorrie FAIR Mia HAMM Michelle FRENCH Nikki SERLENGA Sara WHALEN Shannon MACMILLAN Siri MULLINIX Tiffeny MILBRETT Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Carin GABARRA Carla OVERBECK Cindy PARLOW Joy FAWCETT Julie FOUDY Kristine LILLY Atlanta 1996 Gold football 5 (4 1 0) 13 Mary HARVEY Mia HAMM Michelle AKERS Shannon MACMILLAN Staci WILSON Tiffany ROBERTS Tiffeny MILBRETT Tisha VENTURINI Alexander CUDMORE Charles Albert BARTLIFF Charles James JANUARY John Hartnett JANUARY Joseph LYDON St Louis 1904 Louis John MENGES Silver football 3 pts Oscar B. BROCKMEYER Peter Joseph RATICAN Raymond E. LAWLER Thomas Thurston JANUARY Warren G. BRITTINGHAM - JOHNSON Claude Stanley JAMESON www.downloadexcelfiles.com Cormic F. COSTGROVE DIERKES Frank FROST George Edwin COOKE St Louis 1904 Bronze football 1 pts Harry TATE Henry Wood JAMESON Joseph J. -

Imperialism and the 1999 Women's World Cup

IMPERIALISM AND THE 1999 WOMEN’S WORLD CUP: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES AND NIGERIAN NATIONAL TEAMS IN THE U.S. MEDIA by Michele Canning A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida April 2009 Copyright by Michele Canning 2009 ii ABSTRACT Author: Michele Canning Title: Imperialism and the 1999 Women’s World Cup: Representations of the United States and Nigerian National Teams in the U.S. Media Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Josephine-Beoku-Betts Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2009 This research examines the U.S. media during the 1999 Women’s World Cup from a feminist postcolonial standpoint. This research adds to current feminist scholarship on women and sports by de-centering the global North in its discourse. It reveals the bias of the media through the representation of the United States National Team as a universal “woman” athlete and the standard for international women’s soccer. It further argues that, as a result, the Nigerian National Team was cast in simplistic stereotypes of race, class, ethnicity, and nation, which were often also appropriated and commodified. I emphasize that the Nigerian National Team resisted this construction and fought to secure their position in the global soccer landscape. I conclude that these biased representations, which did not fairly depict or value the contributions of diverse competing teams, were primarily employed to promote and sell the event to a predominantly white middle-class American audience. -

What Employers Should Consider About the Women Soccer Players' Wage Discrimination Claim

04.07.16 What Employers Should Consider about the Women Soccer Players' Wage Discrimination Claim What would you say if you were paid less money for winning than someone else was paid just for showing up? Is that wage discrimination? Yes it is, according to the stars of U.S. Women's National Soccer Team. Last week, five stars of World Cup Champion women's team filed a wage discrimination claim with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) against U.S. Soccer. Hope Solo, Carli Lloyd, Becky Sauerbrunn, Alex Morgan and Megan Rapinoe claim that despite winning more, they are paid less than the men. According to the complaint: − The women's yearly salary is $72,000, compared to the men's yearly salary of $100,000 − The women are paid less for winning exhibition games than men get for simply showing up. The base pay for women to play in exhibition games is $3,600 and they get a bonus of $1,350 if they win; compared to the men who get paid a base of $5,000, with a bonus of $8,166 if they win; − The women receive a lower per diem rate for daily travel expenses. The women receive $50 per day for domestic travel and $60 per day for international travel, whereas the men receive $62.50 and $75.00 respectively; and − "The pay structure for advancement through the rounds of World Cup was so skewed that, in 2015, the men earned $9 million for losing in the round of 16, while the women earned only $2 million for winning the entire tournament. -

Buddha Rising

A visible life YOUR ONLINE LOCAL Hot Stotts! Author Sarah Thebarge’s DAILY NEWS Blazers coach critiques encounter changed lives www.portlandtribune.com up-and-down season Portland— See LIFE, B1 Tribune— See SPORTS, B8 THURSDAY, APRIL 25, 2013 • TWICE CHOSEN THE NATION’S BEST NONDAILY PAPER • WWW.PORTLANDTRIBUNE.COM • PUBLISHED THURSDAY ■ Portlanders embrace Buddhism as Dalai Lama’s visit looms PDC hits fi nancial turning point As funds dry up, agency must change course to stay afl oat By STEVE LAW The Tribune The gravy days are over for the Portland Development Commission, the urban re- newal agency that helped re- vitalize downtown. As the PDC begins shed- ding a third of its staff and faces loss of its primary fund- ing source, agency leaders Humor is frequently a part of the say it must re- Thursday evening service invent itself to FISH conducted by Yangsi Rinpoche, survive. president of Maitripa College in Mayor Char- Southeast Portland. lie Hales hasn’t tipped his hand Services draw a mix of ages, on his approach to urban renew- including student Mikki Columus al and neighborhood revitaliza- (below), but few Asians. tion, but promises to make it a top priority this summer, once more-pressing issues like the city budget shortfall get re- solved. include the many small Buddhist study The agency’s new direction Story by Peter Korn groups meeting in people’s homes, typ- could help shape the future of Photos by Christopher Onstott ically a point of entry for converts, many Portland BUDDHA which number more than 400 accord- neighborhoods ing to one assessment. -

April 13, 2013 - Portland Thorns FC Vs

April 13, 2013 - Portland Thorns FC vs. FC Kansas City GOALS 1 2 F Portland (0-0-1) 0 1 1 FC Kansas City (0-0-1) 1 0 1 SCORING SUMMARY Goal Time Team Goal Scorer Assists Note 1 3 FC Kansas City Renae Cuellar Leigh Ann Robinson 2 67 Portland Christine Sinclair PK CAUTIONS AND EJECTIONS Time Team ## Player Card Reason 43 FC Kansas City 19 Kristie Mewis Yellow Card Delay of Game - Restart 70 Portland 21 Nikki Washington Yellow Card Holding 83 Portland 5 Kathryn Williamson Yellow Card Holding SUBSTITUTIONS Time Team OUT IN 62 Portland #7 Nikki Marshall #4 Emilee O'Neil 64 Portland #8 Angie Kerr #9 Danielle Foxhoven 72 FC Kansas City #7 Casey Loyd #8 Courtney Jones 77 FC Kansas City #9 Merritt Mathias #20 Katie Kelly 81 FC Kansas City #19 Kristie Mewis #15 Erika Tymrak 93+ Portland #21 Nikki Washington #20 Courtney Wetzel Provided by STATS LLC and NWSL - Saturday, April 20, 2013 April 13, 2013 - Portland Thorns FC vs. FC Kansas City SHOTS 1 2 F Portland 3 4 7 FC Kansas City 6 4 10 SHOTS ON GOAL 1 2 F Portland 2 2 4 FC Kansas City 1 2 3 SAVES 1 2 F Portland 0 2 2 FC Kansas City 2 1 3 CORNER KICKS 1 2 F Portland 3 1 4 FC Kansas City 2 1 3 OFFSIDES 1 2 F Portland 0 1 1 FC Kansas City 1 1 2 FOULS 1 2 F Portland 6 7 13 FC Kansas City 6 6 12 Officials: Referee: Kari Seitz Asst.