Transfigurations Exhibition Catalog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subrosa Tactical Biopolitics

14 Common Knowledge and Political Love subRosa . the body has been for women in capitalist society what the factory has been for male waged workers: the primary ground of their exploitation and resistance, as the female body has been appropriated by the state and men, and forced to function as a means for the reproduction and accumulation of labor. Thus the importance which the body in all its aspects—maternity, childbirth, sexuality—has acquired in feminist theory and women’s history has not been misplaced. silvia federici (2004, p. 16) Under capitalism, femininity and gender roles became a “labor” function, and women became a “labor class.”1 On one hand, women’s bodies and labor are revered and exploited as a “natural” resource, a biocommons or commonwealth that is fundamental to maintain- ing and continuing life: women are equated with “the lands,” “mother-earth,” or “the homelands.”2 On the other hand, women’s sexual and reproductive labor—motherhood, pregnancy, childbirth—is economically devalued and socially degraded. In the Biotech Century, women’s bodies have become fl esh labs and Pharma-commons: They are mined for eggs, embryonic tissues, and stem cells for use in medical, and therapeutic experiments, and are employed as gestational wombs in assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Under such conditions, resistant feminist discourses of the “body” emerge as an explicitly biopolitical practice.3 subRosa is a cyberfeminist collective of cultural producers whose practice creates dis- course and experiential knowledge about the intersections of information and biotechnolo- gies in women’s lives, work, and bodies. Since the year 2000, subRosa has produced a variety of performances, participatory events, installations, publications, and Web sites as (cyber)feminist responses to key issues in bio- and digital technologies. -

Selected CV Joan Snyder

JOAN SNYDER Born April 16, 1940, in Highland Park, NJ. Received her A.B. from Douglass College, New Brunswick, NJ in 1962 and her M.F.A. from Rutgers, The State University, New Brunswick, NJ, in 1966. Currently lives and works in Brooklyn and Woodstock, NY. AWARDS 2016 American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Art 2007 The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellowship 1983 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship 1974 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship SELECTED SOLO & GROUP EXHIBITIONS SINCE 1972 2020 The Summer Becomes a Room, CANADA Gallery, New York, NY Friends and Family, curated by Keith Mayerson, Peter Mandenhall Gallery, Pasadena, CA Out of Place: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY 2019-20 Art After Stonewall: 1969-1989, Leslie Lohman Museum of Art (NY), Columbus Museum of Art (OH), Patricia and Philip Frost Museum (FL). 2019 Rosebuds & Rivers, Blain|Southern, London, UK Painters Reply: Experimental Painting in the 1970s and now, curated by Alex Glauber & Alex Logsdail, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY Interwoven, curated by Janie M. Welker, The Art Museum at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY Contemporary American Works on Paper, Anders Wahlstedt Fine Art, New York, NY Mulberry and Canal, Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY 2018-20 Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY 2018-19 Six Chants and One Altar, Anders Wahlstedt Fine Art, New York, NY 2018 Known: Unknown, NY Studio School, New York, NY Scenes From the Collection, The -

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

FALL 2013.Indd

The Print Club of New York Inc Fall 2013 reminder to those of you who still have to send in your President’s Greeting dues. We will move to the waiting list in mid October, Mona Rubin and we don’t want to lose any of you. We will keep you updated about the shipping of the he fall is always an exciting time for print fans as prints. Our goal is to get the first batch out by early we gear up for a new season. November and a second batch in the spring. Therefore Once again we will be receiving our VIP passes it is best to rejoin now and make it onto the initial ship- T ping list. for the IFPDA Print Fair in November, and we have already been invited as guests to the breakfast hosted by As always, we welcome your input about ideas for International Print Center New York on November 9th. events, and please let us know if you would like to join Watch for details about these great membership benefits any committees. That is always the best way to get the and hope there won’t be any big storms this year. most out of the Club. Be sure to mark your calendars for October 21st. Kay In a few days, my husband and I are heading off to Deaux has arranged a remarkably interesting event at a Amsterdam, home to some of the greatest artists of all relatively new studio that combines digital printing with time. We will be staying in an apartment in the neighbor- traditional techniques. -

Lynda Benglis

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG ORAL HISTORY PROJECT The Reminiscences of Lynda Benglis Columbia Center for Oral History Research Columbia University 2016 PREFACE The following oral history is the result of a recorded interview with Lynda Benglis conducted by Cameron Vanderscoff on November 13, 2015. This interview is part of the Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. The reader is asked to bear in mind that s/he is reading a transcript of the spoken word, rather than written prose. Transcription: Audio Transcription Center Session #1 Interviewee: Lynda Benglis Location: New York, New York Interviewer: Cameron Vanderscoff Date: November 13, 2015 Q: Okay, just a brief tag. We’re at 222 on the Bowery [in New York City] to finish with Lynda Benglis. Cameron Vanderscoff here for the Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project and it’s noon. [INTERRUPTION] [Note: Recording resumes as Benglis overviews the events that led her to meeting Rauschenberg. Topics discussed before recording include 222 Bowery, where her neighbors have included William S. Burroughs and John Giorno; her initial move to New York in 1964 to pursue art; her subsequent studies at the Brooklyn Museum Art School; and, via this point of entry to the New York art scene, meeting the individuals discussed next in the transcript.] Benglis: —the Lower East Side, [my then husband] Gordon Hart being a Scotsman. Some Canadians were there and they knew Barnett [“Barney”] Newman. That’s what happened— Robert [“Bob”] Murray and Terry Stevenson. So Stevenson and Murray and there was one other Canadian. But Robert Murray is still around teaching at [School of] Visual Arts [New York] and flies his own plane and lives out in Pennsylvania. -

The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: an Argument for Remembering and Recitation

LEUSCHEN, KATHLEEN T., Ph.D. The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: An Argument for Remembering and Recitation. (2016) Directed by Dr. Nancy Myers. 169 pp. Protesting the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, NJ, second-wave feminists targeted racism, militarism, excessive consumerism, and sexism. Yet nearly fifty years after this protest, popular memory recalls these activists as bra-burners— employing a widespread, derogatory image of feminist activists as trivial and laughably misguided. Contemporary academics, too, have critiqued second-wave feminism as a largely white, middle-class, and essentialist movement, dismissing second-wave practices in favor of more recent, more “progressive” waves of feminism. Following recent rhetorical scholarly investigations into public acts of remembering and forgetting, my dissertation project contests the derogatory characterizations of second-wave feminist activism. I use archival research on consciousness-raising groups to challenge the pejorative representations of these activists within academic and popular memory, and ultimately, to critique telic narratives of feminist progress. In my dissertation, I analyze a rich collection of archival documents— promotional materials, consciousness-raising guidelines, photographs, newsletters, and reflective essays—to demonstrate that consciousness-raising groups were collectives of women engaging in literacy practices—reading, writing, speaking, and listening—to make personal and political material and discursive change, between and across differences among women. As I demonstrate, consciousness-raising, the central practice of second-wave feminism across the 1960s and 1970s, developed out of a collective rhetorical theory that not only linked personal identity to political discourses, but also 1 linked the emotional to the rational in the production of knowledge. -

Fall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move

InsightFall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move The newsletter of the University of Delaware Department of Art History Credits Fall 2019 Editor: Kelsey Underwood Design: Kelsey Underwood Visual Resources: Derek Churchill Business Administrator: Linda Magner Insight is produced by the Department of Art History as a service to alumni and friends of the department. Contact Us Sandy Isenstadt, Professor and Chair, Department of Art History Contents E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8105 Derek Churchill, Director, Visual Resources Center E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 From the Chair 4 Commencement 28 Kelsey Underwood, Communications Coordinator From the Editor 5 Graduate Student News 29 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 Around the Department 6 Graduate Student Awards Linda J. Magner, Business Administrator E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8416 Faculty News 11 Graduate Student Notes Lauri Perkins, Administrative Assistant Faculty Notes Alumni Notes 43 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8415 Undergraduate Student News 23 Donors & Friends 50 Please contact us to pose questions or to provide news that may be posted on the department Undergraduate Student Awards How to Donate website, department social media accounts and/ or used in a future issue of Insight. Undergraduate Student Notes Sign up to receive the Department of Art History monthly newsletter via email at ow.ly/ The University of Delaware is an equal opportunity/affirmative action Top image: Old College Hall. (Photo by Kelsey Underwood) TPvg50w3aql. employer and Title IX institution. For the university’s complete non- discrimination statement, please visit www.udel.edu/home/legal- Right image: William Hogarth, “Scholars at a Lecture” (detail), 1736. -

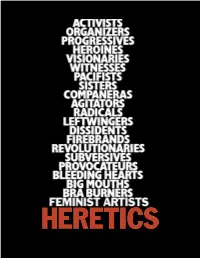

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930S-2007, Bulk 1960-1990

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930s-2007, bulk 1960s-1990, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie L. Ashley and Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 May Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1960s-circa 1980s........................................ 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1950s-2006.................................................................. 7 Series 3: Writings, 1930s-1990s........................................................................... -

CAROLEE SCHNEEMANN B

CAROLEE SCHNEEMANN b. 1939, Fox Chase, PA d. 2019, New Paltz, NY EDUCATION MFA, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois BA, Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson, New York School of Painting and Sculpture, Columbia University, New York The New School for Social Research, New York La Universidad De Puebla, Mexico SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2022 Carolee Schneemann, Barbican Museum, London, UK (forthcoming) 2021 After Carolee: Tender and Fierce, Artpace, San Antonio, TX 2020 Liebeslust und Totentanz (Love’s Joy and Dance of Death), Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur, Switzerland Off the Walls: Gifts from Professor John R. Robertson, Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, TX American Women: The Infinite Journey, La Patinoire Royale, galerie Valérie Bach, Saint-Gilles, Belgium All of Them Witches, curated by Dan Nadal and Laurie Simmons, Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles, CA Don’t Let this be Easy, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN Barney, Scheemann, Shiraga, Tanaka, Fergus McCaffrey, Tokyo, Japan 2019 Carolee Schneeman, les Abattoirs, Toulouse, France Up to and Including Her Limits: After Carolee Schneemann, Museum Susch, Zernez, Switzerland Exhibition of Edition Works, Michele Didier, Paris, France Carolee Schneeman, mfc-michele Didier, Paris, France 2017 Kinetic Painting, Museum fur Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, Germany; MoMA PS 1, Long Island City, NY More Wrong Things, Hales Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2016 Further Evidence – Exhibit A, P·P·O·W, New York, NY Further Evidence – Exhibit B, Galerie Lelong, New York, NY 2015 Kinetic Painting, Museum der Moderne Salzburg, Salzburg, -

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2 Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Memorial for Shulamith Firestone St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, Parish Hall September 23, 2012 Program 4:00–6:00 pm Laya Firestone Seghi Eileen Myles Kathie Sarachild Jo Freeman Ti-Grace Atkinson Marisa Figueiredo Tributes from: Anne Koedt Peggy Dobbins Bev Grant singing May the Work That I Have Done Speak For Me Kate Millett Linda Klein Roxanne Dunbar Robert Roth 3 Open floor for remembrances Lori Hiris singing Hallelujah Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Reception 6:00–6:30 4 Shulamith Firestone Achievements & Education Writer: 1997 Published Airless Spaces. Semiotexte Press 1997. 1970–1993 Published The Dialectic of Sex, Wm. Morrow, 1970, Bantam paperback, 1971. – Translated into over a dozen languages, including Japanese. – Reprinted over a dozen times up through Quill trade edition, 1993. – Contributed to numerous anthologies here and abroad. Editor: Edited the first feminist magazine in the U.S.: 1968 Notes from the First Year: Women’s Liberation 1969 Notes from the Second Year: Women’s Liberation 1970 Consulting Editor: Notes from the Third Year: WL Organizer: 1961–3 Activist in early Civil Rights Movement, notably St. Louis c.o.r.e. (Congress on Racial Equality) 1967–70 Founder-member of Women’s Liberation Movement, notably New York Radical Women, Redstockings, and New York Radical Feminists. Visual Artist: 1978–80 As an artist for the Cultural Council Foundation’s c.e.t.a. Artists’ Project (the first government funded arts project since w.p.a.): – Taught art workshops at Arthur Kill State Prison For Men – Designed and executed solo-outdoor mural on the Lower East Side for City Arts Workshop – As artist-in-residence at Tompkins Square branch of the New York Public Library, developed visual history of the East Village in a historical mural project. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond.