Alignment of Quasar Polarizations with Large-Scale Structures⋆⋆⋆

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantum Detection of Wormholes Carlos Sabín

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Quantum detection of wormholes Carlos Sabín We show how to use quantum metrology to detect a wormhole. A coherent state of the electromagnetic field experiences a phase shift with a slight dependence on the throat radius of a possible distant wormhole. We show that this tiny correction is, in principle, detectable by homodyne measurements Received: 16 February 2017 after long propagation lengths for a wide range of throat radii and distances to the wormhole, even if the detection takes place very far away from the throat, where the spacetime is very close to a flat Accepted: 15 March 2017 geometry. We use realistic parameters from state-of-the-art long-baseline laser interferometry, both Published: xx xx xxxx Earth-based and space-borne. The scheme is, in principle, robust to optical losses and initial mixedness. We have not observed any wormhole in our Universe, although observational-based bounds on their abundance have been established1. The motivation of the search of these objects is twofold. On one hand, the theoretical implications of the existence of topological spacetime shortcuts would entail a challenge to our understanding of deep physical principles such as causality2–5. On the other hand, typical phenomena attributed to black holes can be mimicked by wormholes. Therefore, if wormholes exist the identity of the objects in the center of the galaxies might be questioned6 as well as the origin of the already observed gravitational waves7, 8. For these reasons, there is a renewed interest in the characterization of wormholes9–11 and in their detection by classical means such as gravitational lensing12, 13, among others14. -

Active Galactic Nuclei: a Brief Introduction

Active Galactic Nuclei: a brief introduction Manel Errando Washington University in St. Louis The discovery of quasars 3C 273: The first AGN z=0.158 2 <latexit sha1_base64="4D0JDPO4VKf1BWj0/SwyHGTHSAM=">AAACOXicbVDLSgMxFM34tr6qLt0Ei+BC64wK6kIoPtCNUMU+oNOWTJq2wWRmSO4IZZjfcuNfuBPcuFDErT9g+hC09UC4h3PvJeceLxRcg20/W2PjE5NT0zOzqbn5hcWl9PJKUQeRoqxAAxGoskc0E9xnBeAgWDlUjEhPsJJ3d9rtl+6Z0jzwb6ETsqokLZ83OSVgpHo6754xAQSf111JoK1kTChN8DG+uJI7N6buYRe4ZBo7di129hJ362ew5NJGAFjjfm3V4m0nSerpjJ21e8CjxBmQDBogX08/uY2ARpL5QAXRuuLYIVRjooBTwZKUG2kWEnpHWqxiqE+MmWrcuzzBG0Zp4GagzPMB99TfGzGRWnekZya7rvVwryv+16tE0DysxtwPI2A+7X/UjASGAHdjxA2uGAXRMYRQxY1XTNtEEQom7JQJwRk+eZQUd7POfvboej+TOxnEMYPW0DraRA46QDl0ifKogCh6QC/oDb1bj9ar9WF99kfHrMHOKvoD6+sbuhSrIw==</latexit> <latexit sha1_base64="H7Rv+ZHksM7/70841dw/vasasCQ=">AAACQHicbVDLSgMxFM34tr6qLt0Ei+BCy0TEx0IoPsBlBWuFTlsyaVqDSWZI7ghlmE9z4ye4c+3GhSJuXZmxFXxdCDk599zk5ISxFBZ8/8EbGR0bn5icmi7MzM7NLxQXly5slBjGayySkbkMqeVSaF4DAZJfxoZTFUpeD6+P8n79hhsrIn0O/Zg3Fe1p0RWMgqPaxXpwzCVQfNIOFIUro1KdMJnhA+yXfX832FCsteVOOzgAobjFxG+lhGTBxpe+HrBOBNjiwd5rpZsky9rFUn5BXvgvIENQQsOqtov3QSdiieIamKTWNogfQzOlBgSTPCsEieUxZde0xxsOaurMNNPPADK85pgO7kbGLQ34k/0+kVJlbV+FTpm7tr97Oflfr5FAd6+ZCh0nwDUbPNRNJIYI52nijjCcgew7QJkRzitmV9RQBi7zgguB/P7yX3CxVSbb5f2z7VLlcBjHFFpBq2gdEbSLKugUVVENMXSLHtEzevHuvCfv1XsbSEe84cwy+lHe+wdR361Q</latexit> The power source of quasars • The luminosity (L) of quasars, i.e. how bright they are, can be as high as Lquasar ~ 1012 Lsun ~ 1040 W. • The energy source of quasars is accretion power: - Nuclear fusion: 2 11 1 ∆E =0.007 mc =6 10 W s g− -

A Multimessenger View of Galaxies and Quasars from Now to Mid-Century M

A multimessenger view of galaxies and quasars from now to mid-century M. D’Onofrio 1;∗, P. Marziani 2;∗ 1 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Padova, Padova, Italia 2 National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF), Padua Astronomical Observatory, Italy Correspondence*: Mauro D’Onofrio [email protected] ABSTRACT In the next 30 years, a new generation of space and ground-based telescopes will permit to obtain multi-frequency observations of faint sources and, for the first time in human history, to achieve a deep, almost synoptical monitoring of the whole sky. Gravitational wave observatories will detect a Universe of unseen black holes in the merging process over a broad spectrum of mass. Computing facilities will permit new high-resolution simulations with a deeper physical analysis of the main phenomena occurring at different scales. Given these development lines, we first sketch a panorama of the main instrumental developments expected in the next thirty years, dealing not only with electromagnetic radiation, but also from a multi-messenger perspective that includes gravitational waves, neutrinos, and cosmic rays. We then present how the new instrumentation will make it possible to foster advances in our present understanding of galaxies and quasars. We focus on selected scientific themes that are hotly debated today, in some cases advancing conjectures on the solution of major problems that may become solved in the next 30 years. Keywords: galaxy evolution – quasars – cosmology – supermassive black holes – black hole physics 1 INTRODUCTION: TOWARD MULTIMESSENGER ASTRONOMY The development of astronomy in the second half of the XXth century followed two major lines of improvement: the increase in light gathering power (i.e., the ability to detect fainter objects), and the extension of the frequency domain in the electromagnetic spectrum beyond the traditional optical domain. -

A Supernova Origin for Dust in a High-Redshift Quasar

A SUPERNOVA ORIGIN FOR DUST IN A HIGH-REDSHIFT QUASAR R. Maiolino ∗, R. Schneider †∗, E. Oliva ‡∗, S. Bianchi §, A. Ferrara ¶, F. Mannucci§, M. Pedani‡, M. Roca Sogorb k ∗ INAF - Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo Enrico Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy † “Enrico Fermi” Center, Via Panisperna 89/A, 00184 Roma, Italy ‡ Telescopio Nazionale Galileo, C. Alvarez de Abreu, 70, 38700 S.ta Cruz de La Palma, Spain § CNR-IRA, Sezione di Firenze, Largo Enrico Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy ¶ SISSA/International School for Advanced Studies, Via Beirut 4, 34100 Trieste, Italy k Astrofisico Fco. S`anchez, Universidad de La Laguna, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain Interstellar dust plays a crucial role in the evolution of the Universe by assisting the formation of molecules1, by triggering the formation of the first low-mass stars2, and by absorbing stellar ultraviolet-optical light and subsequently re-emitting it at infrared/millimetre wavelengths. Dust is thought to be produced predominantly in the envelopes of evolved (age >1 Gyr), low-mass stars3. This picture has, however, recently been brought into question by the discovery of large masses of dust in the host galaxies of quasars4,5 at redshift z > 6, when the age of the Universe was less than 1 Gyr. Theoretical studies6,7,8, corroborated by observations of nearby supernova remnants9,10,11, have suggested that supernovae provide a fast and efficient dust formation environment in the early Universe. Here we report infrared observations of a quasar at redshift 6.2, which are used to obtain directly its dust extinction curve. We then show that such a curve is in excellent agreement with supernova dust models. -

Stellar Death: White Dwarfs, Neutron Stars, and Black Holes

Stellar death: White dwarfs, Neutron stars & Black Holes Content Expectaions What happens when fusion stops? Stars are in balance (hydrostatic equilibrium) by radiation pushing outwards and gravity pulling in What will happen once fusion stops? The core of the star collapses spectacularly, leaving behind a dead star (compact object) What is left depends on the mass of the original star: <8 M⦿: white dwarf 8 M⦿ < M < 20 M⦿: neutron star > 20 M⦿: black hole Forming a white dwarf Powerful wind pushes ejects outer layers of star forming a planetary nebula, and exposing the small, dense core (white dwarf) The core is about the radius of Earth Very hot when formed, but no source of energy – will slowly fade away Prevented from collapsing by degenerate electron gas (stiff as a solid) Planetary nebulae (nothing to do with planets!) THE RING NEBULA Planetary nebulae (nothing to do with planets!) THE CAT’S EYE NEBULA Death of massive stars When the core of a massive star collapses, it can overcome electron degeneracy Huge amount of energy BAADE ZWICKY released - big supernova explosion Neutron star: collapse halted by neutron degeneracy (1934: Baade & Zwicky) Black Hole: star so massive, collapse cannot be halted SN1006 1967: Pulsars discovered! Jocelyn Bell and her supervisor Antony Hewish studying radio signals from quasars Discovered recurrent signal every 1.337 seconds! Nicknamed LGM-1 now called PSR B1919+21 BRIGHTNESS TIME NATURE, FEBRUARY 1968 1967: Pulsars discovered! Beams of radiation from spinning neutron star Like a lighthouse Neutron -

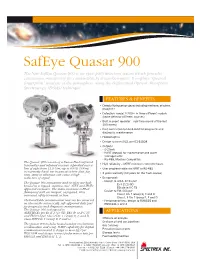

Safeye Quasar 900 the New Safeye Quasar 900 Is an Open Path Detection System Which Provides Continuous Monitoring for Combustible Hydrocarbon Gases

SafEye Quasar 900 The New SafEye Quasar 900 is an open path detection system which provides continuous monitoring for combustible hydrocarbon gases. It employs "spectral fingerprint" analysis of the atmosphere using the Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (DOAS) technique. FEATURES & BENEFITS • Detects Hydrocarbon gases including methane, ethylene, propylene • Detection range: 4-200m in three different models (same detector different sources) • Built in event recorder – real time record of the last 100 events • Fast connection to Hand-Held for prognostic and diagnostic maintenance • Heated optics • Design to meet SIL2, per IEC61508 • Outputs: - 0-20mA - HART protocol for maintenance and asset managements - RS-485, Modbus Compatible The Quasar 900 consists of a Xenon Flash infrared transmitter and infrared receiver, separated over a • High reliability – MTBF minimum 100,000 hours line of sight from 13 ft (4m) up to 650 ft (200m) • User programmable via HART or RS-485 in extremely harsh environments where dust, fog, • 3 years warranty (10 years for the flash source) rain, snow or vibration can cause a high reduction of signal. • Ex approval: - Design to ATEX, IECEx per The Quasar 900 transmitter and receiver are both Ex II 2 (1) GD housed in a rugged, stainless steel, ATEX and IECEx approved enclosure. The main enclosure is EExd EEx de ia II C T5 flameproof with an integral, segregated, EExe - Design to FM, CSA per increased safety terminal section. Class I Div 1 Group B, C and D Class I, II Div 1 Group E, F and D The hand-held communication unit can be connected - Performance test: design to FM6325 and in-situ via the intrinsically safe approved data port EN50241-1 and 2 for prognostic and diagnostic maintenance. -

8. Active Galactic Nuclei. Radio Galaxies and Quasars

8. ACTIVE GALACTIC NUCLEI. RADIO GALAXIES AND QUASARS This Section starts analyzing the phenomenon of extragalactic Active Galactic Nuclei. Here we will essentially discuss their low-photon-energy emissions, while in Sect. 9 we will expand on the high-photon-energy ones. 8.1 Active Galactic Nuclei: Generalities We know that normal galaxies constitute the majority population of cosmic sources in 12 the local universe. Although they may be quite massive (up to 10 M), they are not 11 44 typically very luminous (never more luminous than 10 Lʘ10 erg/sec). For this reason normal galaxies have remained hardly detectable at very large cosmic distances for long time, with recent advances mostly thanks to technological observational improvements. For several decades, since the ’60, the only detectable objects at large cosmic distances belonged to a completely different class of sources, which did not derive their energy from thermonuclear burning in stars. These are the Active Galactic Nuclei, for which we use the acronym AGN. The galaxies hosting them are called active galaxies. For their luminosity, Active Galactic Nuclei and Active Galaxies have plaid a key role in the development of cosmology, further to the fact that they make one of the most important themes of extragalactic astrophysics and High Energy Astrophysics. Apparently, the interest for the Active Galaxies as a population might seem modest, as in the local universe they make a small fraction of normal galaxies, as summarized in the following. There are four main categories of Active Galaxies and AGN: 1. galaxies with an excess of infrared emission and violent activity of star formation (starburst), selected in particular in the far-IR, the luminous (LIRG), ultra-luminous (ULIRG) and hyper-luminous (HYLIRG) galaxies: the 3 classes 11 12 13 have bolometric luminosities >10 L (LIRG), >10 L (ULIRG), >10 L (HYLIRG); 2. -

16.1 Quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei

Quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei Ay1 – Lecture 16 16.1 Quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei: General Properties and Classification Quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei • Highly energetic manifestations in the nuclei of galaxies, powered by accretion onto supermassive massive black holes • Empirical classification schemes have been developed, on the basis of the spectra; but recently, various unification schemes have been developed (~ the same underlying phenomenon) • Evolve strongly in time, with the comoving densities of luminous ones increasing by ~ 103 from z ~ 0 to z ~ 2 • At z ~ 0, at least 30% of all galaxies show some sign of a nuclear activity; ~ 1% can be classified as Seyferts, and ~ 10-6 contain luminous quasars • We think that most or all non-dwarf galaxies contain SMBHs, and thus probably underwent at least one AGN phase AGN, an artist’s view Relativistic jet / illumination cone Central black hole Accretion disk Obscuring dusty torus Observable Properties of AGN • Emission over a broad range of frequencies, radio to γ-rays – Nonthermal radio or X-ray emission is a good way to find AGN – Generally bluer spectra than stars: “UV excess” – Colors unlike those of stars, especially when modified by the intergalactic absorption • Presence of strong, broad emission lines in their spectra 15 • Can reach large luminosities, up to ~ 10 L • Strong variability at all time scales – Implies small physical size of the emission region • Central engines unresolved • Undetectable proper motions due to a large distances All of these have been used to devise methods to discover AGN, and each method has its own limitations and selection effects Broad-Band Spectra of Quasars Radio Loud Radio Quiet UV-Optical Spectra of Quasars Strong, broad emission lines: Balmer lines of hydrogen Prominent lines of abundant ions Quasar Counts For the unobscured, Type 1 QSOs; they may be outnumbered by the obscured ones. -

Quasar Catalogue for the Astrometric Calibration of the Forthcoming ILMT Survey

J. Astrophys. Astr. (2020) 41:22 Ó Indian Academy of Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s12036-020-09642-xSadhana(0123456789().,-volV)FT3](0123456789().,-volV) Quasar catalogue for the astrometric calibration of the forthcoming ILMT survey AMIT KUMAR MANDAL1,4,*, BIKRAM PRADHAN2, JEAN SURDEJ3, C. S. STALIN4, RAM SAGAR4 and BLESSON MATHEW1 1Department of Physics, CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Hosur Road, Bangalore 560 029, India. 2Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences, Manora Peak, Nainital 263 001, India. 3Space Science, Technologies and Astrophysics Research (STAR) Institute, Universite´ de Lie`ge, Alle´edu6 Aouˆt 19c, 4000 Lie`ge, Belgium. 4Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Block II, Koramangala, Bangalore 560 034, India. E-mail: [email protected] MS received 27 May 2020; accepted 13 July 2020 Abstract. Quasars are ideal targets to use for astrometric calibration of large scale astronomical surveys as they have negligible proper motion and parallax. The forthcoming 4-m International Liquid Mirror Tele- scope (ILMT) will survey the sky that covers a width of about 270. To carry out astrometric calibration of the ILMT observations, we aimed to compile a list of quasars with accurate equatorial coordinates and falling in the ILMT stripe. Towards this, we cross-correlated all the quasars that are known till the present date with the sources in the Gaia-DR2 catalogue, as the Gaia-DR2 sources have position uncertainties as small as a few milli arcsec (mas). We present here the results of this cross-correlation which is a catalogue of 6738 quasars that is suitable for astrometric calibration of the ILMT fields. -

Quasar Jet Emission Model Applied to the Microquasar GRS 1915+105

A&A 415, L35–L38 (2004) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20040010 & c ESO 2004 Astrophysics Quasar jet emission model applied to the microquasar GRS 1915+105 M. T¨urler1;2, T. J.-L. Courvoisier1;2,S.Chaty3;4,andY.Fuchs4 1 INTEGRAL Science Data Centre, ch. d’Ecogia 16, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland 2 Observatoire de Gen`eve, ch. des Maillettes 51, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland Letter to the Editor 3 Universit´e Paris 7, 2 place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France 4 Service d’Astrophysique, DSM/DAPNIA/SAp, CEA/Saclay, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, Cedex, France Received 18 December 2003 / Accepted 14 January 2004 Abstract. The true nature of the radio emitting material observed to be moving relativistically in quasars and microquasars is still unclear. The microquasar community usually interprets them as distinct clouds of plasma, while the extragalactic com- munity prefers a shock wave model. Here we show that the synchrotron variability pattern of the microquasar GRS 1915+105 observed on 15 May 1997 can be reproduced by the standard shock model for extragalactic jets, which describes well the long-term behaviour of the quasar 3C 273. This strengthens the analogy between the two classes of objects and suggests that the physics of relativistic jets is independent of the mass of the black hole. The model parameters we derive for GRS 1915+105 correspond to a rather dissipative jet flow, which is only mildly relativistic with a speed of 0:60 c. We can also estimate that the shock waves form in the jet at a distance of about 1 AU from the black hole. -

Formation of Supermassive Black Holes

Formation of Supermassive Black Holes by Stefan Taubenberger 1 Galaxies with BHs in their center 2 Centaurus A 3 Centaurus A 4 M87 / Virgo A 5 M87 / Virgo A 6 Index 1) Observational constraints Quasars found at z~6 Quasar number density σ MBH - relation Recent observation of Black Hole binaries Quiescent SMBHs 2) 3 basic scenarios of SMBH formation Collapse of a gas cloud or a supermassive star to a SMBH in the early universe Runaway growth by accretion Mergers of two Black Holes 3) One possible model of SMBH formation Observation Scenarios possible model 7 Quasars at z~6 z = 5,8 Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) 2002: quasar at z = 5,8 Quasars Ù massive accreting BHs z = 4,75 First massive BHs must have existed 1 Gyr after the Big Bang ⇨ very rapid formation process required Observation: z~6 quasars Scenarios possible model 8 Quasar number density Quasar density peaks at z ~ 2 (~ 3 billion years after Big Bang) since then decrease in quasar density: Seyfert galaxies (active galaxies, but less luminous than quasars) show different behaviour: maximum shifted to lower redshifts (z ~ 1) maximum is higher ⇨ Seyfert galaxies more common than quasars What is the physical difference? SMBH formation model should explain both phenomena Observation: number dens. Scenarios possible model 9 Quasar number density Quasar density peaks at z ~ 2 (~ 3 billion years after Big Bang) since then decrease in quasar density: Seyfert galaxies (active galaxies, but less luminous than quasars) show different behaviour: maximum shifted to lower redshifts (z ~ 1) maximum is higher ⇨ Seyfert galaxies more common than quasars What is the physical difference? SMBH formation model Hasinger et al. -

Quasar-Galaxy Associations

Mon Not R Astron So c ? Quasargalaxy asso ciations P A Thomas R L Webster and M J Drinkwater Astronomy Centre MAPS University of Sussex Brighton BN QH School of Physics University of Melbourne Parkvil le Victoria Australia AngloAustralian Observatory Coonabarabran NSW Australia August ABSTRACT There is controversy ab out the measurement of statistical asso ciations b etween bright quasars and faint presumably foreground galaxies We lo ok at the distribution of galax ies around an unbiased sample of bright mo derate redshift quasars using a new statistic based on the separation of the quasar and its nearest neighbour galaxy We nd a signicant excess of close neighbours at separations less than ab out arcsec which we attribute to the magnication by gravitational lensing of quasars which would otherwise b e to o faint to b e included in our sample Ab out one quarter to one third of the quasars are so aected although the allowed error in this fraction is large Key words quasars general gravitational lensing signicant excess of galaxies near mo derately high red INTRODUCTION shift quasars Tyson Webster et al Fugmann In this pap er we lo ok at the asso ciation b etween quasars and and Hintzen Romanishin Valdes How foreground galaxies We nd a signicant excess over that ever some more recent studies eg Crampton McClure exp ected from a random distribution which we interpret as Fletcher and Yee Filipp enko Tang claim no b eing due to gravitational lensing ie many of the quasars statistical excess though quantitative