How Hong Kong Was Lost SINOPSIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong: Key Issues in 2021

December 23, 2020 Hong Kong: Key Issues in 2021 The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR, country or with external elements to endanger national or Hong Kong) is a city located off the southern coast of security.” The NPCSC and the HKSAR government have Guangdong Province, People’s Republic of China (PRC or stated that the NSL was necessary to restore order China). More than 90% of Hong Kong’s population is following the large-scale protests of 2019. For more about ethnically Chinese. The first language of the vast majority the 2019 protests, see CRS In Focus IF11295, Hong Kong’s is Cantonese, a variety of Chinese different from what is Protests of 2019. spoken in most of the PRC. Hong Kong at a Glance Under the provisions of a 1984 international treaty known Population (2020): 7.5 million as the “Joint Declaration,” sovereignty over Hong Kong Area: 1,082 square kilometers (418 square miles) transferred from the United Kingdom to the PRC on July 1, Per Capita GDP (2019): HK$381,714 (US$48,938) 1997. In the Joint Declaration, China pledged the former British colony “will enjoy a high degree of autonomy, Life Expectancy (at birth, 2018): Men: 82.2 years; except in foreign and defence affairs,” and “will be vested Women: 88.1 years with executive, legislative and independent judicial power, Leadership: Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor including that of final adjudication.” China also promised Source: Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department that the “[r]ights and freedoms, including those of the person, of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, The Hong Kong Police Force (HKPF) has arrested dozens of travel, of movement, of correspondence, of strike, of of people for alleged NSL violations. -

Monthly Report HK

April in Hong Kong 30.4.2021/No. 208 A condensed press review prepared by the Consulate General of Switzerland in HK Contents Switzerland in the local press ......................................................................................................................... 2 US stops short of branding Switzerland as a currency manipulator (SCMP, Apr.17): ....................................... 2 CS unloads CHF2.1bn of stocks linked to Bill Hwang’s Archegos (SCMP, Apr.6): ........................................... 2 Foreign Policy / International Relations ......................................................................................................... 2 US Secretary of State Blinken condemns sentencing of HK activists (SCMP, Apr.18): .................................... 2 Beijing accuses UK of sheltering “wanted criminals” (TheStandard, Apr.8): .................................................... 2 £43m (CHF55m) package to support HK families arriving to UK (SCMP, Apr.8): ............................................. 2 HK Gov rejects US report on ‘dismantling’ of HK (SCMP, HK Statement US Statement, Apr.1): ...................... 2 Mainland .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Beijing attacks on Bar Association President and calls for his removal (SCMP, Apr.25): ................................. 2 Beijing ready to fight back as Western powers consider sanctions over HK (SCMP, Apr.15): ......................... -

Freedom of Speech Should Prevail but It Must Not Misinform

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Tuesday, March 10, 2020 | 9 COMMENTHK Freedom of speech This time, things should prevail but it really are di erent for Hong Kong he 2020 budget is over, delivered in must not misinform unexpectedly trying times as a result of the coronavirus that is attacking says it’s vital for the media to be fair, the community in every possible Ho Lok-sang Tway: physically, psychologically and economi- cally. Predictably, public attention has homed objective and balanced when reporting on police in on the proposal to give every Hong Kong permanent resident a cash sum of HK$10,000 Rachel Cartland operations at a time when our city is deeply polarized ($1,287), a handsome amount by any stan- The author is a co-host of RTHK’s Backchat dards. It is, of course, not the fi rst time that radio program and supporter of various wel- ommissioner of was the reason people had lost faith this has been done, but a handout from the fare NGOs. She is a former assistant director of Police Chris Tang in the force. government is normally controversial. social welfare. Ping-keung recently To be fair, in the face of extreme Some who favor such gestures have argued lodged a complaint to violence and criminal activities on a that it is only reasonable, in good times, to It may seem strange, but it the Communications massive scale, often life-threatening, hand back to the community some of what is true that avoiding means Authority and Direc- such as what we have witnessed in they have contributed either through taxes or tor of Broadcasting Ho Lok-sang Hong Kong since June, it is to be through their labor. -

CE Policy Address Should Show Courage to Tackle Deep-Rooted

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Monday, October 12, 2020 | 7 COMMENTHK Editor’s note: China Daily Hong Kong Edition has launched a photo-shar- ing campaign on Instagram. You can share your photos by tagging #hk24hr, and we’ll choose the best ones to publish in the newspaper. CE Policy Address should Engrossed A masked boy busy with his smartphone sits on a luggage cart show courage to tackle inside the Tai Po wet market. EDMOND TANG / deep-rooted problems CHINA DAILY Tony Kwok says the lack of accountability among professional union groups that enables subversive behavior, threatens security needs to be addressed he recent announce- that the chief executive announces ment by the Hong drastic steps in her policy speech to Kong Police Force rectify this aberration which impacts on the accreditation national security. She should con- HK must keep up with mainland of reporters to cover sider setting up a board of governors its events and opera- to replace the current toothless advi- tions is overdue and Tony Kwok sory council, to take over the supervi- pledge on carbon neutrality target The author is an adjunct professor of to be applauded. Henceforth, it will sion of the station. She could have HKU Space, and a council member of allow only government-registered the Government Information Service n Sept 22, President Xi Jinping pro- T the Chinese Association of Hong Kong taking over the news department of news media, and internationally and Macao Studies. vided a pleasant surprise to the nation recognized and renowned foreign RTHK, or at least form a joint unit and the world. -

Hong Kong Protests

Country Policy and Information Note China: Hong Kong protests Version 1.0 February 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

What Do Hong Kong-Related Sanctions Mean for U.S. Financial Institutions? a Swiftly Changing Landscape

ARTICLE What do Hong Kong-Related Sanctions mean for U.S. Financial Institutions? A Swiftly Changing Landscape Developments in Hong Kong and the U.S.’s reaction have been swift since June 30, 2020, when China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) passed the national security law (NSL) -- promulgated by Carrie Lam, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). The U.S. considers the NSL another action by China to erode the autonomy and rights promised to Hong Kong in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong, an international treaty preserving Hong Kong’s freedoms for 50 years from 1997 to 2047.1 Accordingly, on July 14, 2020, President Trump signed both the Hong Kong Autonomy Act of 2020 (HKAA) and The President's Executive Order on Hong Kong Normalization (E.O. 13936). The HKAA requires the President, under certain conditions, to impose sanctions against non-U.S. or “foreign” persons (i.e., entities and individuals) and financial institutions that contravene China’s obligations with respect to Hong Kong’s autonomy. E.O. 13936 declares the situation in Hong Kong a threat to the national security, foreign policy and economy of the U.S., due to the broad power China has given itself under the NSL to control prosecutions in Hong Kong, conduct proceedings in secret, and expel journalists, human rights organizations and other outside groups, making it more difficult to hold China accountable for its treatment of the Hong Kong people. In response, E.O. 13936 implements provisions of the HKAA and sets forth additional sanctions, including criteria for designating and blocking foreign persons and eliminating preferential treatment for Hong Kong in various areas of U.S. -

China's National Security Law for Hong Kong

China’s National Security Law for Hong Kong: Issues for Congress Updated August 3, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46473 SUMMARY R46473 China’s National Security Law for Hong Kong: August 3, 2020 Issues for Congress Susan V. Lawrence On June 30, 2020, China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) passed a Specialist in Asian Affairs national security law (NSL) for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Hong Kong’s Chief Executive promulgated it in Hong Kong later the same day. The law is widely seen Michael F. Martin as undermining the HKSAR’s once-high degree of autonomy and eroding the rights promised to Specialist in Asian Affairs Hong Kong in the 1984 Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong, an international treaty between the People’s Republic of China (China, or PRC) and the United Kingdom covering the 50 years from 1997 to 2047. The NSL criminalizes four broadly defined categories of offenses: secession, subversion, organization and perpetration of terrorist activities, and “collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security” in relation to the HKSAR. Persons convicted of violating the NSL can be sentenced to up to life in prison. China’s central government can, at its or the HKSAR’s discretion, exercise jurisdiction over alleged violations of the law and prosecute and adjudicate the cases in mainland China. The law apparently applies to alleged violations committed by anyone, anywhere in the world, including in the United States. The HKSAR and PRC governments have already begun implementing the NSL, including setting up the new entities the law requires. -

Cm20200507-Translate-E.Pdf

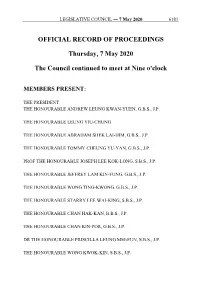

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 7 May 2020 6181 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 7 May 2020 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S., J.P. 6182 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 7 May 2020 THE HONOURABLE MRS REGINA IP LAU SUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSE WAI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CLAUDIA MO THE HONOURABLE STEVEN HO CHUN-YIN, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE FRANKIE YICK CHI-MING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WU CHI-WAI, M.H. THE HONOURABLE YIU SI-WING, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE MA FUNG-KWOK, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHARLES PETER MOK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN CHI-CHUEN THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAN-PAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KENNETH LEUNG THE HONOURABLE ALICE MAK MEI-KUEN, B.B.S., J.P. -

Table of Contents

Last updated: April 1, 2021 Timeline of Executive Actions on China (2017–2021) This document covers executive actions taken by the Administration of President Donald Trump directed at China. Executive actions include (1) executive orders from the president and (2) other significant measures taken by federal agencies relating to U.S.-China policy. Between 2017 and 2021, the Trump Administration issued eight executive orders that primarily involved China. The Trump Administration issued an additional seven executive orders that did not explicitly target China but affected key policy areas relating to the U.S.-China relationship.1 In addition to these 15 executive orders, the Commission identified 116 China-related measures taken by White House and other executive departments and agencies from 2017 to 2021. A list of all currently identified executive actions, including both executive orders and measures taken by executive departments and agencies, can be found in the appendix of this document. This document is based upon press releases by the White House and by executive departments and agencies. Table of Contents Executive Orders Directly Targeting China .................................................................................................. 2 Executive Orders on Issues Critical to the U.S.-China Relationship ............................................................ 6 Appendix: Executive Actions on China (2017–2021) ................................................................................ 10 1 Executive orders in this -

Election Committee

6 | FOCUSHK Friday, August 13, 2021 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY Selection starts for new panel In Hong Kong’s first major election under the improved electoral system, 1,016 candidates are vying for 982 seats on the expanded Election Committee, whose 1,500 members will nominate lawmaker candidates and elect 40 legislators among themselves, in addition to the long-standing task of nominating and choosing the city’s chief executive. Gang Wen breaks down the reshaped body. Responsibilities of the Election Committee • Nominates candidates for the chief executive • Nominates legislative candidates • Elects the chief executive • Elects 40 legislative councilors among its members Who are the voters? Nomination period: Aug 6-12 Polling day: Sept 19 There are individual voters and corporate The term: 5 years (Oct 22, 2021 – Oct 21, 2026) voters. Both must register as Election Com- mittee Subsector Voters. Candidate Eligibility Individual voters will choose committee members for four subsectors, including the Members Chairperson: Review Committee the chief secretary for administration, John Lee Ka-chiu Heung Yee Kuk, and representatives of Hong O cial members Kong members of eligible national organiza- It assesses and validates the eligibility of 1. the secretary for constitutional and mainland a airs, Erick Tsang Kwok-wai candidates for the Election Committee, chief 2. the secretary for home a airs, Caspar Tsui Ying-wai tions; corporate voters will pick members for executive and the Legislative Council. 3. the secretary for security, Chris Tang Ping-keung the other subsectors. Its review decisions made on the advice of the Non-o cial members 1. Elsie Leung Oi-sie Election SAR government’s national security committee will Chairperson O cial members Non-o cial members 2. -

COMMENTHK Backing Rioters, Western Media Are, Basically, Anti

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Monday, March 2, 2020 | 9 COMMENTHK Backing rioters, Western Police funding: Adequate media are, basically, resources vital to defend HK ver since violent protest- the United Kingdom and the ers launched their war United States. Again, net guns, on society last June, the which release material to entan- police force has had to gle suspects in a way that does anti-Chinese and racist Ebear the brunt. Although they not endanger life, are also used have valiantly sought to pro- Grenville Cross by the police in places like Japan, Andre Vltchek points out what the West and tect people, businesses, public The author is a senior counsel, Taiwan and the US, and can be of facilities and even courts from law professor and criminal great utility. its biased journalists term as ‘pro-democracy’ black-clad mobs, they have paid justice analyst, and was previ- The police, moreover, hope to a heavy price. O cers have been ously the director of public spend about HK$77 million on alays aggressively disrespectful of HK police attacked with petrol bombs, sav- prosecutions of the Hong Kong replacing six armored vehicles, agely assaulted, and even set on Special Administrative Region and, once achieved, this will also fi re, but they have not fl inched, government. strengthen their operational n Friday, I was having lunch with although many have been hospi- capability. the senior superintendent of the talized. on e ective policing. Although the government’s Hong Kong Police Force, Kit Tse Although the COVID-19 out- In his budget -

MIRRORING HK SECURITY Cases from an Outbreak in the City of Melbourne That Has Prompted a Strict Lockdown

FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho www.macaudailytimes.com.mo THURSDAY T. 24º/ 28º Air Quality Good MOP 8.00 3597 “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” N.º 13 Aug 2020 HKD 10.00 THREE YOUNG PEOPLE, INCLUDING NPC ALLOWS MACAU, HUMAN RIGHTS ACTIVIST TWO STUDENTS, HAVE COME JASON CHAO SENDS WARNING FORWARD AS VICTIMS OF BLACKMAIL HK LAWYERS TO WORK TO MACAU ENGLISH AND INVOLVING NUDE VIDEO CHATS IN GBA CITIES PORTUGUESE PRESS P2 P2 P3 AP PHOTO HO IAT SENG ON THE WAY TO BEIJING Australia’s state of Victoria yesterday reported a record 21 virus deaths and 410 new MIRRORING HK SECURITY cases from an outbreak in the city of Melbourne that has prompted a strict lockdown. State P3 Premier Daniel Andrews said 16 of the deaths LAW NOT MANDATORY were linked to aged-care facilities. The number of new cases in Victoria is down from the peak, giving authorities some hope the outbreak is waning. AP PHOTO New Zealand Health authorities were scrambling to trace the source of a new outbreak as the nation’s largest city went back into lockdown. The four cases reported from one Auckland household are New Zealand’s first locally transmitted cases in 102 days. The 22 others were in mandatory quarantine after returning from travel abroad. Two of the infected people had visited the tourist city of Rotorua last weekend while suffering symptoms, and authorities were trying to track their movements. AP PHOTO India’s coronavirus caseload topped 2.3 million after adding 60,963 new cases in the last 24 hours.