Jasmine Javascript Testing Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practical Unit Testing for Embedded Systems Part 1 PARASOFT WHITE PAPER

Practical Unit Testing for Embedded Systems Part 1 PARASOFT WHITE PAPER Table of Contents Introduction 2 Basics of Unit Testing 2 Benefits 2 Critics 3 Practical Unit Testing in Embedded Development 3 The system under test 3 Importing uVision projects 4 Configure the C++test project for Unit Testing 6 Configure uVision project for Unit Testing 8 Configure results transmission 9 Deal with target limitations 10 Prepare test suite and first exemplary test case 12 Deploy it and collect results 12 Page 1 www.parasoft.com Introduction The idea of unit testing has been around for many years. "Test early, test often" is a mantra that concerns unit testing as well. However, in practice, not many software projects have the luxury of a decent and up-to-date unit test suite. This may change, especially for embedded systems, as the demand for delivering quality software continues to grow. International standards, like IEC-61508-3, ISO/DIS-26262, or DO-178B, demand module testing for a given functional safety level. Unit testing at the module level helps to achieve this requirement. Yet, even if functional safety is not a concern, the cost of a recall—both in terms of direct expenses and in lost credibility—justifies spending a little more time and effort to ensure that our released software does not cause any unpleasant surprises. In this article, we will show how to prepare, maintain, and benefit from setting up unit tests for a simplified simulated ASR module. We will use a Keil evaluation board MCBSTM32E with Cortex-M3 MCU, MDK-ARM with the new ULINK Pro debug and trace adapter, and Parasoft C++test Unit Testing Framework. -

Histcoroy Pyright for Online Information and Ordering of This and Other Manning Books, Please Visit Topwicws W.Manning.Com

www.allitebooks.com HistCoroy pyright For online information and ordering of this and other Manning books, please visit Topwicws w.manning.com. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity. For more information, please contact Tutorials Special Sales Department Offers & D e al s Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road Highligh ts PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 Email: [email protected] Settings ©2017 by Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved. Support No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or Sign Out transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps. Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed on acidfree paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental chlorine. Manning Publications Co. PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 www.allitebooks.com Development editor: Cynthia Kane Review editor: Aleksandar Dragosavljević Technical development editor: Stan Bice Project editors: Kevin Sullivan, David Novak Copyeditor: Sharon Wilkey Proofreader: Melody Dolab Technical proofreader: Doug Warren Typesetter and cover design: Marija Tudor ISBN 9781617292576 Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 – EBM – 22 21 20 19 18 17 www.allitebooks.com HistPoray rt 1. -

Parallel, Cross-Platform Unit Testing for Real-Time Embedded Systems

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2017 Parallel, Cross-Platform Unit Testing for Real-Time Embedded Systems Tosapon Pankumhang University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Pankumhang, Tosapon, "Parallel, Cross-Platform Unit Testing for Real-Time Embedded Systems" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1353. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1353 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. PARALLEL, CROSS-PLATFORM UNIT TESTING FOR REAL-TIME EMBEDDED SYSTEMS __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Daniel Felix Ritchie School of Engineering and Computer Science University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Tosapon Pankumhang August 2017 Advisor: Matthew J. Rutherford ©Copyright by Tosapon Pankumhang 2017 All Rights Reserved Author: Tosapon Pankumhang Title: PARALLEL, CROSS-PLATFORM UNIT TESTING FOR REAL-TIME EMBEDDED SYSTEMS Advisor: Matthew J. Rutherford Degree Date: August 2017 ABSTRACT Embedded systems are used in a wide variety of applications (e.g., automotive, agricultural, home security, industrial, medical, military, and aerospace) due to their small size, low-energy consumption, and the ability to control real-time peripheral devices precisely. These systems, however, are different from each other in many aspects: processors, memory size, develop applications/OS, hardware interfaces, and software loading methods. -

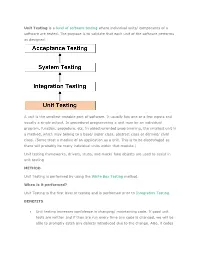

Unit Testing Is a Level of Software Testing Where Individual Units/ Components of a Software Are Tested. the Purpose Is to Valid

Unit Testing is a level of software testing where individual units/ components of a software are tested. The purpose is to validate that each unit of the software performs as designed. A unit is the smallest testable part of software. It usually has one or a few inputs and usually a single output. In procedural programming a unit may be an individual program, function, procedure, etc. In object-oriented programming, the smallest unit is a method, which may belong to a base/ super class, abstract class or derived/ child class. (Some treat a module of an application as a unit. This is to be discouraged as there will probably be many individual units within that module.) Unit testing frameworks, drivers, stubs, and mock/ fake objects are used to assist in unit testing. METHOD Unit Testing is performed by using the White Box Testing method. When is it performed? Unit Testing is the first level of testing and is performed prior to Integration Testing. BENEFITS Unit testing increases confidence in changing/ maintaining code. If good unit tests are written and if they are run every time any code is changed, we will be able to promptly catch any defects introduced due to the change. Also, if codes are already made less interdependent to make unit testing possible, the unintended impact of changes to any code is less. Codes are more reusable. In order to make unit testing possible, codes need to be modular. This means that codes are easier to reuse. Development is faster. How? If you do not have unit testing in place, you write your code and perform that fuzzy ‘developer test’ (You set some breakpoints, fire up the GUI, provide a few inputs that hopefully hit your code and hope that you are all set.) If you have unit testing in place, you write the test, write the code and run the test. -

Including Jquery Is Not an Answer! - Design, Techniques and Tools for Larger JS Apps

Including jQuery is not an answer! - Design, techniques and tools for larger JS apps Trifork A/S, Headquarters Margrethepladsen 4, DK-8000 Århus C, Denmark [email protected] Karl Krukow http://www.trifork.com Trifork Geek Night March 15st, 2011, Trifork, Aarhus What is the question, then? Does your JavaScript look like this? 2 3 What about your server side code? 4 5 Non-functional requirements for the Server-side . Maintainability and extensibility . Technical quality – e.g. modularity, reuse, separation of concerns – automated testing – continuous integration/deployment – Tool support (static analysis, compilers, IDEs) . Productivity . Performant . Appropriate architecture and design . … 6 Why so different? . “Front-end” programming isn't 'real' programming? . JavaScript isn't a 'real' language? – Browsers are impossible... That's just the way it is... The problem is only going to get worse! ● JS apps will get larger and more complex. ● More logic and computation on the client. ● HTML5 and mobile web will require more programming. ● We have to test and maintain these apps. ● We will have harder requirements for performance (e.g. mobile). 7 8 NO Including jQuery is NOT an answer to these problems. (Neither is any other js library) You need to do more. 9 Improving quality on client side code . The goal of this talk is to motivate and help you improve the technical quality of your JavaScript projects . Three main points. To improve non-functional quality: – you need to understand the language and host APIs. – you need design, structure and file-organization as much (or even more) for JavaScript as you do in other languages, e.g. -

Testing and Debugging Tools for Reproducible Research

Testing and debugging Tools for Reproducible Research Karl Broman Biostatistics & Medical Informatics, UW–Madison kbroman.org github.com/kbroman @kwbroman Course web: kbroman.org/Tools4RR We spend a lot of time debugging. We’d spend a lot less time if we tested our code properly. We want to get the right answers. We can’t be sure that we’ve done so without testing our code. Set up a formal testing system, so that you can be confident in your code, and so that problems are identified and corrected early. Even with a careful testing system, you’ll still spend time debugging. Debugging can be frustrating, but the right tools and skills can speed the process. "I tried it, and it worked." 2 This is about the limit of most programmers’ testing efforts. But: Does it still work? Can you reproduce what you did? With what variety of inputs did you try? "It's not that we don't test our code, it's that we don't store our tests so they can be re-run automatically." – Hadley Wickham R Journal 3(1):5–10, 2011 3 This is from Hadley’s paper about his testthat package. Types of tests ▶ Check inputs – Stop if the inputs aren't as expected. ▶ Unit tests – For each small function: does it give the right results in specific cases? ▶ Integration tests – Check that larger multi-function tasks are working. ▶ Regression tests – Compare output to saved results, to check that things that worked continue working. 4 Your first line of defense should be to include checks of the inputs to a function: If they don’t meet your specifications, you should issue an error or warning. -

The Art, Science, and Engineering of Fuzzing: a Survey

1 The Art, Science, and Engineering of Fuzzing: A Survey Valentin J.M. Manes,` HyungSeok Han, Choongwoo Han, Sang Kil Cha, Manuel Egele, Edward J. Schwartz, and Maverick Woo Abstract—Among the many software vulnerability discovery techniques available today, fuzzing has remained highly popular due to its conceptual simplicity, its low barrier to deployment, and its vast amount of empirical evidence in discovering real-world software vulnerabilities. At a high level, fuzzing refers to a process of repeatedly running a program with generated inputs that may be syntactically or semantically malformed. While researchers and practitioners alike have invested a large and diverse effort towards improving fuzzing in recent years, this surge of work has also made it difficult to gain a comprehensive and coherent view of fuzzing. To help preserve and bring coherence to the vast literature of fuzzing, this paper presents a unified, general-purpose model of fuzzing together with a taxonomy of the current fuzzing literature. We methodically explore the design decisions at every stage of our model fuzzer by surveying the related literature and innovations in the art, science, and engineering that make modern-day fuzzers effective. Index Terms—software security, automated software testing, fuzzing. ✦ 1 INTRODUCTION Figure 1 on p. 5) and an increasing number of fuzzing Ever since its introduction in the early 1990s [152], fuzzing studies appear at major security conferences (e.g. [225], has remained one of the most widely-deployed techniques [52], [37], [176], [83], [239]). In addition, the blogosphere is to discover software security vulnerabilities. At a high level, filled with many success stories of fuzzing, some of which fuzzing refers to a process of repeatedly running a program also contain what we consider to be gems that warrant a with generated inputs that may be syntactically or seman- permanent place in the literature. -

Programming in HTML5 with Javascript and CSS3 Ebook

spine = 1.28” Programming in HTML5 with JavaScript and CSS3 and CSS3 JavaScript in HTML5 with Programming Designed to help enterprise administrators develop real-world, About You job-role-specific skills—this Training Guide focuses on deploying This Training Guide will be most useful and managing core infrastructure services in Windows Server 2012. to IT professionals who have at least Programming Build hands-on expertise through a series of lessons, exercises, three years of experience administering and suggested practices—and help maximize your performance previous versions of Windows Server in midsize to large environments. on the job. About the Author This Microsoft Training Guide: Mitch Tulloch is a widely recognized in HTML5 with • Provides in-depth, hands-on training you take at your own pace expert on Windows administration and has been awarded Microsoft® MVP • Focuses on job-role-specific expertise for deploying and status for his contributions supporting managing Windows Server 2012 core services those who deploy and use Microsoft • Creates a foundation of skills which, along with on-the-job platforms, products, and solutions. He experience, can be measured by Microsoft Certification exams is the author of Introducing Windows JavaScript and such as 70-410 Server 2012 and the upcoming Windows Server 2012 Virtualization Inside Out. Sharpen your skills. Increase your expertise. • Plan a migration to Windows Server 2012 About the Practices CSS3 • Deploy servers and domain controllers For most practices, we recommend using a Hyper-V virtualized • Administer Active Directory® and enable advanced features environment. Some practices will • Ensure DHCP availability and implement DNSSEC require physical servers. -

Lab 6: Testing Software Studio Datalab, CS, NTHU Notice

Lab 6: Testing Software Studio DataLab, CS, NTHU Notice • This lab is about software development good practices • Interesting for those who like software development and want to go deeper • Good to optimize your development time Outline • Introduction to Testing • Simple testing in JS • Testing with Karma • Configuring Karma • Karma demo: Simple test • Karma demo: Weather Mood • Karma demo: Timer App • Conclusions Outline • Introduction to Testing • Simple testing in JS • Testing with Karma • Configuring Karma • Karma demo: Simple test • Karma demo: Weather Mood • Karma demo: Timer App • Conclusions What is testing? Is it important? Actually, we are always doing some kind of testing.. And expecting some result.. And expecting some result.. Sometimes we just open our app and start clicking to see results Why test like a machine? We can write programs to automatically test our application! Most common type of test: Unit test Unit test • “Unit testing is a method by which individual units of source code are tested to determine if they are fit for use. A unit is the smallest testable part of an application.” - Wikipedia Good unit test properties • It should be automated and repeatable • It should be easy to implement • Once it’s written, it should remain for future use • Anyone should be able to run it • It should run at the push of a button • It should run quickly The art of Unit Testing, Roy Osherove Many frameworks for unit tests in several languages Common procedure • Assertion: A statement that a predicate is expected to always be true at that point in the code. -Wikipedia Common procedure • We write our application and want it to do something, so we write a test to see if it’s behaving as we expect Common procedure • Pseudocode: But how to do that in JS? Outline • Introduction to Testing • Simple testing in JS • Testing with Karma • Configuring Karma • Karma demo: Simple test • Karma demo: Weather Mood • Karma demo: Timer App • Conclusions Simple testing: expect library and jsbin Test passed: Test didn’t pass: This is ok for testing some simple functions. -

Open Source Used in SD-AVC 2.2.0

Open Source Used In SD-AVC 2.2.0 Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. Text Part Number: 78EE117C99-189242242 Open Source Used In SD-AVC 2.2.0 1 This document contains licenses and notices for open source software used in this product. With respect to the free/open source software listed in this document, if you have any questions or wish to receive a copy of any source code to which you may be entitled under the applicable free/open source license(s) (such as the GNU Lesser/General Public License), please contact us at [email protected]. In your requests please include the following reference number 78EE117C99-189242242 Contents 1.1 @angular/angular 5.1.0 1.1.1 Available under license 1.2 @angular/material 5.2.3 1.2.1 Available under license 1.3 angular 1.5.9 1.3.1 Available under license 1.4 angular animate 1.5.9 1.5 angular cookies 1.5.9 1.6 angular local storage 0.5.2 1.7 angular touch 1.5.9 1.8 angular ui router 0.3.2 1.9 angular ui-grid 4.0.4 1.10 angular-ui-bootstrap 2.3.2 1.10.1 Available under license 1.11 angular2-moment 1.7.0 1.11.1 Available under license 1.12 angularJs 1.5.9 1.13 bootbox.js 4.4.0 1.14 Bootstrap 3.3.7 1.14.1 Available under license 1.15 Bootstrap 4 4.0.0 1.15.1 Available under license 1.16 chart.js 2.7.2 1.16.1 Available under license 1.17 commons-io 2.5 1.17.1 Available under license Open Source Used In SD-AVC 2.2.0 2 1.18 commons-text 1.4 1.18.1 -

Background Goal Unit Testing Regression Testing Automation

Streamlining a Workflow Jeffrey Falgout Daniel Wilkey [email protected] [email protected] Science, Discovery, and the Universe Bloomberg L.P. Computer Science and Mathematics Major Background Regression Testing Jenkins instance would begin running all Bloomberg L.P.'s main product is a Another useful tool to have in unit and regression tests. This Jenkins job desktop application which provides sufficiently complex systems is a suite would then report the results on the financial tools. Bloomberg L.P. of regression tests. Regression testing Phabricator review and signal the author employs many computer programmers allows you to test very high level in an appropriate way. The previous to maintain, update, and add new behavior which can detect low level workflow required manual intervention to features to this product. bugs. run tests. This new workflow only the The product the code base was developer to create his feature branch in implementing has a record/playback order for all tests to be run automatically. Goal feature. This was leveraged to create a Many of the tasks that a programmer regression testing framework. This has to perform as part of a team can be framework leveraged the unit testing automated. The goal of this project was framework wherever possible. to work with a team to automate tasks At various points during the playback, where possible and make them easier callback methods would be invoked. An example of the new workflow, where a Jenkins where impossible. These methods could have testing logic to instance will automatically run tests and update the make sure the application was in the peer review. -

Introduction to Unit Testing

INTRODUCTION TO UNIT TESTING In C#, you can think of a unit as a method. You thus write a unit test by writing something that tests a method. For example, let’s say that we had the aforementioned Calculator class and that it contained an Add(int, int) method. Let’s say that you want to write some code to test that method. public class CalculatorTester { public void TestAdd() { var calculator = new Calculator(); if (calculator.Add(2, 2) == 4) Console.WriteLine("Success"); else Console.WriteLine("Failure"); } } Let’s take a look now at what some code written for an actual unit test framework (MS Test) looks like. [TestClass] public class CalculatorTests { [TestMethod] public void TestMethod1() { var calculator = new Calculator(); Assert.AreEqual(4, calculator.Add(2, 2)); } } Notice the attributes, TestClass and TestMethod. Those exist simply to tell the unit test framework to pay attention to them when executing the unit test suite. When you want to get results, you invoke the unit test runner, and it executes all methods decorated like this, compiling the results into a visually pleasing report that you can view. Let’s take a look at your top 3 unit test framework options for C#. MSTest/Visual Studio MSTest was actually the name of a command line tool for executing tests, MSTest ships with Visual Studio, so you have it right out of the box, in your IDE, without doing anything. With MSTest, getting that setup is as easy as File->New Project. Then, when you write a test, you can right click on it and execute, having your result displayed in the IDE One of the most frequent knocks on MSTest is that of performance.