Maurice Sendak Is Best Known As the Illustrator of More Than 100 Picture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Beatrix Potter Admirers, Society News the Beatrix Potter Society

Approaching "Beatrix's side" of Windermere, on the ferry from Bowness Photo: J. Sullivan Dear Beatrix Potter Admirers, The Beatrix Potter Welcome back to another mix of articles, events and Society happenings - it is always an adventure to see where Beatrix will take us! Interested in learning more about Beatrix Potter? Consider joining the Society News Society. Meet others who are passionate about The Society's Committee, following the AGM in early March: Beatrix Potter, her life and works. You will also receive the quarterly Journal and Newsletter, full of interesting articles about Miss Potter and the Society's efforts and events. Find the Membership form for download, and more information about the Society here. Save the Date: May 20, 2017: Spring Meeting, Sloane Club, London. Rear row, l to r: Angela Black, Meetings Secretary; Miranda Gore Browne; Sue Smith, Treasurer; Helen Duder, Archivist and merchandise specialist. June 9-11, 2017: Front row, l to r: Rowena Godfrey, Chairman; Kathy Cole, Secretary Photo: Betsy Bray "Beatrix Potter in New London on the Thames River: A Symposium at the Linda Lear Center for The Society is still looking for Members to take over the roles Special Collections and of Treasurer, Sales Manager, and Editor of the Journal and Archives", Connecticut Newsletter, as well as someone to help create publications. If College, New London, CT. you can volunteer, please contact [email protected]. September 9-10, 2017: Autumn Meeting, Lake District, UK. December 2, 2017: Festive Gathering, Sloane Club, London. Quick Links Email us at: [email protected] m Read the previous issue of "Pottering About" here. -

Guided Reading Level I

Guided Reading Book List It can be difficult finding books that meet your child's reading ability. Below is a list of suggested books according to their guided reading level. Guided Reading Level I Airport by Byron Barton Albert the Albatross by Syd Hoff Allergies by Sharon Gordon All Tutus Should Be Pink by Sheri Brownrigg Alligators All around by Maurice Sendak Ambulances by Marcia Freeman Angus and the Cat by Marjorie Flack Apples and Pumpkins by Ann Rockwell Are You My Mother? by P.D. Eastman Asthma by Sharon Gordon The Bear’s Bicycle by Emilie McLeod Benny Bakes a Cake by Eve Rice Big Dog, Little Dog by P.D. Eastman The Big Hungry Bear by Don and Audrey Wood The Bike Lesson by Stan and Jan Berenstain Busy Buzzing Bumblebees by Alvin Schwartz Charles M. Schulz by Cheryl Carlson Come and Have Fun by Edith Thacher Hurd The Dinosaur Who Lived in My Backyard by Brendan Hennessy Dragon Gets By by Dav Pilkey Dragon’s Fat Cat by Dav Pilkey Earaches by Sharon Gordon Father Bear Comes Home by Else Minarik Fire Engines by Marcia Freeman A Friend for Dragon by Dav Pilkey Go away, Dog by Joan Nodset Goodnight, Owl! by Pat Hutchins Hattie and the Fox by Mem Fox Hello Cat, You Need a Hat by Rita Gelman Henny Penny by Paul Galdone Hiccups for Elephant by James Preller It’s Not Easy Being a Bunny by Marilyn Sadler Jim Meets the Thing by Miriam Cohen Just a Mess by Mercer Mayer Leo the Late Bloomer by Robert Kraus The Lighthouse Children by Syd Hoff A Look at China by Helen Frost A Look at Mexico by Helen Frost Lost in the Museum by Miriam Cohen Maurice -

Reading and Writing Sendak

LIT 6934: Seminar Instructor: John Cech(V) Tuesdays 6-8 CBD 0230 Reading and Writing Sendak The Artist, The Art of the Picture Book, The Golden Age of American Children’s Literature, and the Archetypes of Childhood “Let the wild rumpus start!” This seminar focuses on the art of Maurice Sendak, one of the key, shaping figures of American and, indeed, world children’s literature for more than half a century. Sendak’s influences on the art of the picture book as well as our thinking about childhood has been ubiquitous and profound. The seminar will explore Sendak works (in print and other media) with special attention to the rich historical sources of his works, his archetypal poetics, his revisioning of the form of the picture book, and his redefinition of the role of the artist creating works for young people in contemporary culture. Along with discussions of his core works, participants in the seminar will respond to Sendak’s works imaginatively, through a series of bi-weekly creative projects and a final, longer work. Readings Ruth Kraus, AHole is to Dig Sendak,The Sign on Rosie's Door Ruth Kraus, AVery Special House Sendak,The Junniper Tree Sendak,Kenny's Window Sendak,The N ut shell Library Sendak,Where the Wild Things Are Sendak,In the Night Kitchen Sendak,Outside Over There Sendak,Higglety Pigglety Pop! Randall Jarrell, The Animal Family Randall Jarrell, The Bat Poet Sendak,We're All in the Dumps with с and Guy Sendak,Caldecott & Co.: Notes on Be and Pictures Seminar Assignments A series of short creative papers and a presentation for the seminar A final term project Office Hours Tuesdays and Thursdays 2:00 - 3:30 and by appointment Office: 4364 Turlington Phone: (352) 294-2861 Email: [email protected] Schedule of Discussion Topics January 7 Introductions. -

American Masters 200 List Finaljan2014

Premiere Date # American Masters Program Title (Month-YY) Subject Name 1 ARTHUR MILLER: PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS On the Set of "Death of a Salesman" June-86 Arthur Miller 2 PHILIP JOHNSON: A SELF PORTRAIT June-86 Philip Johnson 3 KATHERINE ANNE PORTER: THE EYE OF MEMORY July-86 Katherine Anne Porter 4 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 1) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 5 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 2) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 6 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 3) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 7 BILLIE HOLIDAY: THE LONG NIGHT OF LADY DAY August-86 Billie Holiday 8 JAMES LEVINE: THE LIFE IN MUSIC August-86 James Levine 9 AARON COPLAND: A SELF PORTRAIT August-86 Aaron Copland 10 THOMAS EAKINS: A MOTION PORTRAIT August-86 Thomas Eakins 11 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE September-86 Georgia O'Keeffe 12 EUGENE O'NEILL: A GLORY OF GHOSTS September-86 Eugene O'Neill 13 ISAAC IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER July-87 Isaac Bashevis Singer 14 DIRECTED BY WILLIAM WYLER July-87 William Wyler 15 ARTHUR RUBENSTEIN: RUBENSTEIN REMEMBERED July-87 Arthur Rubinstein 16 ALWIN NIKOLAIS AND MURRAY LOUIS: NIK AND MURRAY July-87 Alwin Nikolais/Murray Louis 17 GEORGE GERSHWIN REMEMBERED August-87 George Gershwin 18 MAURICE SENDAK: MON CHER PAPA August-87 Maurice Sendak 19 THE NEGRO ENSEMBLE COMPANY September-87 Negro Ensemble Co. 20 UNANSWERED PRAYERS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF TRUMAN CAPOTE September-87 Truman Capote 21 THE TEN YEAR LUNCH: THE WIT AND LEGEND OF THE ALGONQUIN ROUND TABLE September-87 Algonquin Round Table 22 BUSTER KEATON: A HARD ACT TO FOLLOW (Part 1) November-87 Buster Keaton 23 BUSTER KEATON: -

(ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to Present

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to present 2014 Medal Winner: Locomotive, written and illustrated by Brian Floca (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing) 2014 Honor Books: Journey, written and illustrated by Aaron Becker (Candlewick Press) Flora and the Flamingo, written and illustrated by Molly Idle (Chronicle Books) Mr. Wuffles! written and illustrated by David Wiesner (Clarion Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing) 2013 Medal Winner: This Is Not My Hat, written and illustrated by Jon Klassen (Candlewick Press) 2013 Honor Books: Creepy Carrots!, illustrated by Peter Brown, written by Aaron Reynolds (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division) Extra Yarn, illustrated by Jon Klassen, written by Mac Barnett (Balzer + Bray, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) Green, illustrated and written by Laura Vaccaro Seeger (Neal Porter Books, an imprint of Roaring Brook Press) One Cool Friend, illustrated by David Small, written by Toni Buzzeo (Dial Books for Young Readers, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group) Sleep Like a Tiger, illustrated by Pamela Zagarenski, written by Mary Logue (Houghton Mifflin Books for Children, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company) 2012 Medal Winner: A Ball for Daisy by Chris Raschka (Schwartz & Wade Books, an imprint of Random House Children's Books, a division of Random House, Inc.) 2013 Honor Books: Blackout by John Rocco (Disney · Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group) Grandpa Green by Lane Smith (Roaring Brook Press, a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings Limited Partnership) Me...Jane by Patrick McDonnell (Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.) 2011 Medal Winner: A Sick Day for Amos McGee, illustrated by Erin E. -

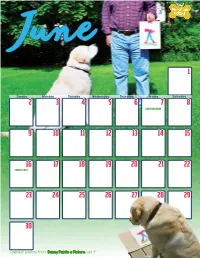

Calendar Photos from Danny Paints a Picture, Set 4 June 2019 Cut and Paste Activity Calendar Activity

June 1 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dad’s birthDay 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Father’s Day 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Calendar photos from Danny Paints a Picture, set 4 June 2019 Cut and Paste Activity Calendar Activity Find the June birthdays, cut out the picture that goes with each, and paste it on their special day on the calendar. 6 Cynthia Rylant was born June 6, 1954 in West Virginia. Her youth in the Appalachian region provided the setting for her first children’s book, When I was Young in the Mountains. A prolific writer of children’s literature, Rylant explores themes of friendship, emotions, and growing up. She has been awarded the Newbery Medal for A Fine White Dust, and several other stories have been named Newbery Honor and Caldecott Honor books. 10 The writer and illustrator of the popular Where the Wild Things Are, Maurice Sendak was born June 10, 1928. First an illustrator, Sendak worked on more than eighty books written by various authors before he wrote his own story. Kenny’s Window, published in 1956, was Sendak’s first title of which he was both author and illustrator. Seven years later he produced Where the Wild Things Are and earned the Caldecott Medal. 18 Another Caldecott Medal winner is Chris Van Allsburg. Born June 18, 1949, Allsburg is best known as the author and illustrator of Jumanji and The Polar Express, both of which have been made into major motion pictures. -

Today's Fbi. It's for You

PLEASE BE AWARE THAT THIS IS AN ADVERTISEMENT, NOT A JOB POSTING FOR THE SPECIAL AGENT POSITION. The FBI is collecting resumes of those interested in future employment as an FBI Agent. Individuals that meet the FBI’s Special Agent preliminary requirements will be notified by email once the actual application is available. TODAY'S FBI. IT'S FOR YOU. The strength of the FBI is its people – employees from different backgrounds, each possessing a myriad of skills, working together to ensure the safety of our communities and the nation. Each year, people from every industry, ethnicity, and environment apply to become members of the most prestigious law enforcement agency in the world. A unique, challenging and life-changing experience that will stretch you beyond your comprehension, the Special Agent position is more than a job – it is a calling to protect and defend your country, uphold and enforce the laws in your community and provide law enforcement assistance where and when, necessary. Bring your skills and dedication. We’ll make you an Agent. FBI Special Agents are responsible for enforcing over 300 federal statutes and conducting sensitive national security investigations. A career as a Special Agent offers unparalleled opportunities for new experiences and personal and professional growth. Listed below are some of our most sought after specialties: FBI SPECIAL AGENT: CERTIFIED PROFESSIONAL ACCOUNTANT (CPA) All crime leaves a money trail - at the FBI, we track it back to its source, investigate the participants and develop a case. As such, the FBI is seeking Certified Professional Accountants (CPAs) for the Special Agent position. -

Curriculum Guide 5Th - 8Th Grades

Final drawing for Where the Wild Things Are, © 1963 by Maurice Sendak, all rights reserved. Curriculum Guide 5th - 8th Grades In a Nutshell:the Worlds of Maurice Sendak is on display jan 4 - feb 24, 2012 l main library l 301 york street In a Nutshell: The Worlds of Maurice Sendak was organized by the Rosenbach Museum & Library, Philadelphia, and developed by Nextbook, Inc., a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting Jewish literature, culture, and ideas, and the American Library Association Public Programs Office. The national tour of the exhibit has been made possible by grants from the Charles H. Revson Foundation, the Righteous Persons Foundation, the David Berg Foundation, and an anonymous donor, with additional support from Tablet Magazine: A New Read on Jewish Life. About the Exhibit About Maurice Sendak will be held at the Main Library, 301 York St., downtown, January 4th to February 24th, 2012. Popular children’s author Maurice Sendak’s typically American childhood in New York City inspired many of his most beloved books, such as Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen. Illustrations in those works are populated with friends, family, and the sights, sounds and smells of New York in the 1930s. But Sendak was also drawn to photos of ancestors, and he developed a fascination with the shtetl world of European Jews. This exhibit, curated by Patrick Rodgers of the Rosenbach Museum & Library Maurice Sendak comes from Brooklyn, New York. in Philadelphia, reveals the push and pull of New and Old He was born in 1928, the youngest of three children. -

The Department of Justice and the Limits of the New Deal State, 1933-1945

THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE LIMITS OF THE NEW DEAL STATE, 1933-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Ponomarenko December 2010 © 2011 by Maria Ponomarenko. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/ms252by4094 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Kennedy, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard White, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mariano-Florentino Cuellar Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements My principal thanks go to my adviser, David M. -

Red Scare: FBI and the Origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943 Schmidt, Regin

www.ssoar.info Red scare: FBI and the origins of anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943 Schmidt, Regin Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Schmidt, R. (2004). Red scare: FBI and the origins of anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-271396 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Copyright © Museum Tusculanum Press RED SCARE Regin Schmidt: Red Scare. FBI and the origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943; e-book. 2004. ISBN 87 635 0012 4 Copyright © Museum Tusculanum Press Regin Schmidt: Red Scare. FBI and the origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943; e-book. 2004. ISBN 87 635 0012 4 Copyright © Museum Tusculanum Press Regin Schmidt RED SCARE FBI and the Origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919-1943 e-Book Regin Schmidt: Red Scare. FBI and the origins of Anticommunism MUSEUM TUSCULANUM PRESS in the United States, 1919-1943; e-book. 2004. ISBN 87 635 0012 4 UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN 2000 [e-book – 2004] Copyright © Museum Tusculanum Press Regin Schmidt: Red Scare. -

THESIS ARTISTS' BOOKS and CHILDREN's BOOKS Elizabeth A

THESIS ARTISTS’ BOOKS AND CHILDREN’S BOOKS Elizabeth A. Curren Art and the Book In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Art and the Book Corcoran College of Art + Design Washington, DC Spring 2013 © 2013 Elizabeth Ann Curren All Rights Reserved CORCORAN COLLEGE OF ART + DESIGN May 6, 2013 WE HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER OUR SUPERVISION BY ELIZABETH A. CURREN ENTITLED ARTISTS’ BOOKS AND CHILDREN’S BOOKS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING, IN PART, REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTs IN ART AND THE BOOK. Graduate Thesis Committee: (Signature of Student) Elizabeth A. Curren (Printed Name of Student) (Signature of Thesis Reader) Georgia Deal (Printed Name of Thesis Reader) (Signature of Thesis Reader) Sarah Noreen Hurtt (Printed Name of Thesis Reader) (Signature of Program Chair and Advisor) Kerry McAleer-Keeler (Printed Name of Program Director and Advisor) Acknowledgements Many people have given generously of their time, their experience and their insights to guide me through this thesis; I am extremely grateful to all of them. The faculty of the Art and The Book Program at the Corcoran College of Art + Design have been most encouraging: Kerry McAleer-Keeler, Director, and Professors Georgia Deal, Sarah Noreen Hurtt, Antje Kharchi, Dennis O’Neil and Casey Smith. Students of the Corcoran’s Art and the Book program have come to the rescue many times. Many librarians gave me advice and suggestions. Mark Dimunation, Daniel DiSimone and Eric Frazier of the Rare Books and Special Collections at the Library of Congress have provided research support and valuable comments during the best internship opportunity anyone can ever have. -

Theatre Review: “Really Rosie” by Kevin M. O'toole Weston

Theatre Review: “Really Rosie” By Kevin M. O’Toole Weston Playhouse Theatre Company began its 2017 summer season with its Young Company production of “Really Rosie,” based upon the stories and poems of children’s author Maurice Sendak, with a musical score by famed tunesmith Carole King. The enthusiastic reception by last Friday afternoon’s audience, comprised largely of youngsters with their parent or grandparent in tow, confirmed the show’s appeal to small fry. Throughout the show, the talented ensemble of actors enlisted several audience members to become a peripheral part of the performance. Each cast member conveyed an accessible, non-threatening demeanor that never condescended to the children, many of whom were being introduced to live theatre. The skeletal plot of “Really Rosie” takes a day in the life of Rosie, who orchestrates a make- believe movie of her growing life with her pals on Avenue P. A little solipsism goes a long way. Being the product of Maurice Sendak, who penned “Where the Wild Things Are,” all is colorful and fun, but any life lessons are muddled. For example, one of Rosie’s cohorts, Pierre, petulantly played by Gideon Chicos, doggedly repeats his mantra: “I don’t care.” The titular moral of Pierre’s musical number is to care for others but Pierre never really does, even after he is eaten by a lion (and lives!). The production’s structure afforded each cast member an opportunity to shine. As Rosie, Allie Seibold gave the cloying title character a commanding presence with her crisp singing voice. As Rosie’s needy younger sibling, Chicken Soup, Jonathan Gomolka, reminded the audience that little brothers want their own way, too.