Looking for Abraham's City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genesis, Book of 2. E

II • 933 GENESIS, BOOK OF Pharaoh's infatuation with Sarai, the defeat of the four Genesis 2:4a in the Greek translation: "This is the book of kings and the promise of descendants. There are a num the origins (geneseos) of heaven and earth." The book is ber of events which are added to, or more detailed than, called Genesis in the Septuagint, whence the name came the biblical version: Abram's dream, predicting how Sarai into the Vulgate and eventually into modern usage. In will save his life (and in which he and his wife are symbol Jewish tradition the first word of the book serves as its ized by a cedar and a palm tree); a visit by three Egyptians name, thus the book is called BeriPSit. The origin of the (one named Hirkanos) to Abram and their subsequent name is easier to ascertain than most other aspects of the report of Sarai's beauty to Pharaoh; an account of Abram's book, which will be treated under the following headings: prayer, the affliction of the Egyptians, and their subse quent healing; and a description of the land to be inher A. Text ited by Abram's descendants. Stylistically, the Apocryphon B. Sources may be described as a pseudepigraphon, since events are l. J related in the first person with the patriarchs Lamech, 2. E Noah and Abram in turn acting as narrator, though from 3. p 22.18 (MT 14:21) to the end of the published text (22.34) 4. The Promises Writer the narrative is in the third person. -

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 Author(s): Lewis Bayles Paton Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259319 . Accessed: 09/04/2012 16:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXXII Part I 1913 Israel's Conquest of Canaan Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 LEWIS BAYLES PATON HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY problem of Old Testament history is more fundamental NO than that of the manner in which the conquest of Canaan was effected by the Hebrew tribes. If they came unitedly, there is a possibility that they were united in the desert and in Egypt. If their invasions were separated by wide intervals of time, there is no probability that they were united in their earlier history. Our estimate of the Patriarchal and the Mosaic traditions is thus conditioned upon the answer that we give to this question. -

An Examination of Scriptural and Archaeological Evidences for the Historicity of Biblical Patriarchs

Asian Journal of Humanities and Social Studies (ISSN: 2321 – 2799) Volume 03 – Issue 05, October 2015 An Examination of Scriptural and Archaeological Evidences for the Historicity of Biblical Patriarchs Faith O. Adebayo The Nigerian Baptist Theological Seminary, Ogbomoso, Oyo-State, Nigeria Email: ocheniadey [AT] gmail.com _________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT---- The term Patriarch is the designation given to the three major ancestors of the Israelites. The ancestors are: Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. However, the twelve sons of Jacob are sometimes refers to as Patriarchs, especially with the significance role played by Joseph for the sustenance of the race. The life and experiences of the Patriarchs are recorded in the book of Genesis. The stories of these Patriarchs were traditional tales which were handed down through many generations before the Old Testament writers collected them in the book of Genesis. The historicity of the Old Testament narratives about the Patriarchs has been a major debate among biblical critics, while archaeological finds has also tends to shed light on some of the events and customs attributed to the Patriarchs in the narratives. Hence, the writer in this paper will present the scriptural positions on the three Patriarchs, the archaeological discoveries that have aid the historicity of the Patriarchal narratives, and hence considered the consonance and the dissonance between the scriptural positions and archaeological discoveries that has shed light on the historicity of the Patriarchs. Keywords--- Patriarch, Archaeology, Customs, Religion, Narratives _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. INTRODUCTION The term Patriarch is the designation given to the three major ancestors of the Israelites. The ancestors are: Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. -

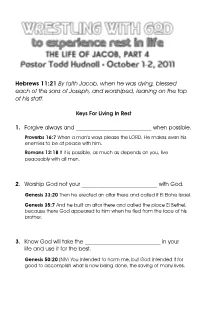

Hebrews 11:21 by Faith Jacob, When He Was Dying, Blessed Each of The

4. Trust that God is your __________________________ even when it doesn’t seem like it. Genesis 48:15 (NIV) “May the God before whom my fathers Abraham and Isaac walked, the God who has been my shepherd all my life to this day.” Hebrews 11:21 By faith Jacob, when he was dying, blessed 5. Expect God to fulfill His __________________________ without your manipulation. each of the sons of Joseph, and worshiped, leaning on the top of his staff. Genesis 48:14 (NIV) But Israel reached out his right hand and put it on Ephraim’s head, though he was the younger, and crossing his arms, he put his left hand on Manasseh’s head, even though Manasseh was Keys For Living In Rest the firstborn. 1. Forgive always and __________________________ when possible. Proverbs 16:7 When a man’s ways please the LORD, He makes even his enemies to be at peace with him. Group Discussion Questions Romans 12:18 If it is possible, as much as depends on you, live 1. Read Romans 12:18. What is the difference between living peaceably with all men. peaceably and being reconciled? Are there any relationships in your life where you need to establish peace? Are there any relationships in your life where you 2. Worship God not your __________________________ with God. need to reconcile? What do you think you need to do? Genesis 33:20 Then he erected an altar there and called it El Elohe Israel. 2. Why is it important to worship God and not your experience Genesis 35:7 And he built an altar there and called the place El Bethel, with God? Has that ever been a problem for you? Explain. -

The Book of Hebrews

The Book of Hebrews Introduction to Study: Who wrote the Epistle to the Hebrews? A. T. Robertson, in his Greek NT study, quotes Eusebius as saying, “who wrote the Epistle God only 1 knows.” Though there is an impressive list of early Bible students that attributed the epistle to the apostle Paul (i.e., Pantaenus [AD 180], Clement of Alexander [AD 187], Origen [AD 185], The Council of Antioch [AD 264], Jerome [AD 392], and Augustine of Hippo in North Africa), there is equally an impressive list of those who disagree. Tertullian [AD 190] ascribed the epistle of Hebrews to Barnabas. Those who support a Pauline epistle claim that the apostle wrote the book in the Hebrew language for the Hebrews and that Luke translated it into Greek. Still others claim that another author wrote the epistle and Paul translated it into Greek. Lastly, some claim that Paul provided the ideas for the epistle by inspiration and that one of his contemporaries (Luke, Barnabas, Apollos, Silas, Aquila, Mark, or Clement of Rome) actually composed the epistle. The fact of the matter is that we just do not have enough clear textual proof to make a precise unequivocal judgment one way or the other. The following notes will refer to the author as ‘the author of Hebrews,’ whether that be Paul or some other. Is the Book of Hebrews an Inspired Work? Bible skeptics have questioned the authenticity (canonicity) of Hebrews simply because of its unknown author. There are three proofs that should suffice the reader of the inspiration of Hebrews as it takes its rightful place in the NT. -

Hebrews 11-23-31

Hebrews 11-23-31 Prayer for illumination: please join me in prayer…. Sermon introduction: If you live long enough you will face a crisis. Many of you have faced multiple crises in the last year. Some of you have faced a health crisis. Some of you have faced a family crisis. Some of you have lost loved ones. Some of you have faced a work crisis. Some of you have faced a significant relational crisis. Some of you have faced a financial crisis. Some of you have experienced a school crisis. Unfortunately, crises come in all shapes and sizes. How do you respond when a crisis strikes? Some people panic, others plan like crazy, some work harder, others isolate themselves, manipulate others, or medicate with substances, food, or media. None of these responses brings joy and peace! How should we respond? This brings us to the book of Hebrews once again. The recipients of this letter faced a crisis. Hebrews 10:32–34 (ESV) — 32 But recall the former days when, after you were enlightened, you endured a hard struggle with sufferings, 33 sometimes being publicly exposed to reproach and affliction, and sometimes being partners with those so treated. 34 For you had compassion on those in prison, and you joyfully accepted the plundering of your property, since you knew that you yourselves had a better possession and an abiding one. The original audience experienced persecution and affliction simply for being Christians. Some even had their personal property vandalized. They were outcasts. This was a crisis. How should they respond to this crisis? How should you respond to crisis? We find the answer in Hebrews 11:23-31. -

Wordplay in Genesis 2:25-3:1 and He

Vol. 42:1 (165) January – March 2014 WORDPLAY IN GENESIS 2:25-3:1 AND HE CALLED BY THE NAME OF THE LORD QUEEN ATHALIAH: THE DAUGHTER OF AHAB OR OMRI? YAH: A NAME OF GOD THE TRIAL OF JEREMIAH AND THE KILLING OF URIAH THE PROPHET SHEPHERDING AS A METAPHOR SAUL AND GENOCIDE SERAH BAT ASHER IN RABBINIC LITERATURE PROOFTEXT THAT ELKANAH RATHER THAN HANNAH CONSECRATED SAMUEL AS A NAZIRITE BOOK REVIEW: ONKELOS ON THE TORAH: UNDERSTANDING THE BIBLE BOOK REVIEW: JPS BIBLE COMMENTARY: JONAH LETTER TO THE EDITOR www.jewishbible.org THE JEWISH BIBLE QUARTERLY In cooperation with THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, THE JEWISH AGENCY AIMS AND SCOPE The Jewish Bible Quarterly provides timely, authoritative studies on biblical themes. As the only Jewish-sponsored English-language journal devoted exclusively to the Bible, it is an essential source of information for anyone working in Bible studies. The Journal pub- lishes original articles, book reviews, a triennial calendar of Bible reading and correspond- ence. Publishers and authors: if you would like to propose a book for review, please send two review copies to BOOK REVIEW EDITOR, POB 29002, Jerusalem, Israel. Books will be reviewed at the discretion of the editorial staff. Review copies will not be returned. The Jewish Bible Quarterly (ISSN 0792-3910) is published in January, April, July and October by the Jewish Bible Association , POB 29002, Jerusalem, Israel, a registered Israe- li nonprofit association (#58-019-398-5). All subscriptions prepaid for complete volume year only. The subscription price for 2014 (volume 42) is $60. Our email address: [email protected] and our website: www.jewishbible.org . -

Livingbyfaith-Print.Pdf

Two men stood side by side on a dock one day, peering Otherwise, there’s no way you can navigate through today out into the broad ocean. One looked out and said, “I see a and make it to tomorrow! ship!” The other guy turned his gaze in the same direction and declared, “There’s no ship out there.” “Yes there is,” the first man insisted. “Look,” his friend countered, “I just had an eye exam. I’ve got perfect twenty-twenty vision and I’m telling you, I don’t see a ship.” “Take my word for it. There is a ship.” “How can you be so sure?” the second man asked, squinting hard as he looked out to sea. “I see it clearly through my binoculars.” Your Perspective To a great degree, living a successful Christian life is a No Turning Back matter of perspective. The clarity of your vision can make all the difference and sharp-sightedness often depends on The writer found himself addressing a most perplexing the focusing power of the lens you are using. problem. He was faced with a congregation of people who were contemplating quitting the Christian faith. Even distant images can be brought into crystal clarity with They were considering throwing in the towel because the right optics. In the same way, if we look at our lives they were no longer sure that following the path was through the lens of Scripture, we might discover an ocean worth the pain. They thought that it might just be too liner we failed to notice earlier. -

God of the Fathers”

THE NABATAEAN “GOD OF THE FATHERS” John F. Healey In 1929 Albrecht Alt, in his ground-shifting essay on “Der Gott der Väter”,1 invoked the epigraphic evidence provided by the Nabataean inscriptions to support his argument that the Hebrew patriarchal narratives showed traces of earlier nomadic religious tradition. This approach combined the nineteenth/early twentieth-century interest in casting light from Arabia on the patriarchal narratives with the early twentieth-century form-critical effort to get back to the earliest forms and elements of the texts. Subsequent scholarship has thrown doubt on many of the basic theses and conclusions of Alt and his followers, such as the assumption that the family unit formed the basis of the origins of Israelite religion2 and even his minimal confidence over the recovery of history from the texts.3 The Ugaritic texts were published soon after Alt wrote his essay and patriarchal religion could then be seen in the new light of El-worship.4 In the context of these develop- ments the Nabataean evidence was marginalized on the grounds that it is very late in date. It receives scant attention in later discussions. I cannot contribute usefully to the discussion of the nomadic or other origins of Israelite religion or the traditions of the Book of Genesis, but it is noteworthy that the patriarchs are presented in the Pentateuch as settling nomads, whether this is historically authentic information or not. This concept certainly became part of the Israelite self-under- standing: “A wandering Aramaean was my father” (Deut. 26:5). Several of Alt’s fundamental points remain valid: in the narratives available 1 A. -

Better Than the Blood of Abel? Some Remarks on Abel in Hebrews 12:24

Tyndale Bulletin 67.1 (2016) 127-136 BETTER THAN THE BLOOD OF ABEL? SOME REMARKS ON ABEL IN HEBREWS 12:24 Kyu Seop Kim ([email protected]) Summary The sudden mention of Abel in Hebrews 12:24 has elicited a multiplicity of interpretations, but despite its significance, the meaning of ‘Abel’ (τὸν Ἅβελ) has not attracted the careful attention that it deserves. This study argues that τὸν Ἅβελ in Hebrews 12:24 refers to Abel as an example who speaks to us through his right observation of the cult. Accordingly, Hebrews 12:24b means that Christ’s cult is superior to the Jewish ritual. This interpretation fits exactly with the adjacent context contrasting Sinai and Zion symbols. 1. Introduction The sudden mention of Abel in Hebrews 12:24 has elicited a multiplicity of interpretations, but despite its significance, this topic has not attracted the careful attention that it deserves. Traditionally, scholars assert that ‘Abel’ (τὸν Ἅβελ) in Hebrews 12:24 refers to ‘the blood of Abel’.1 Most Bible translators also read ‘than Abel’ (παρὰ τὸν 1 E.g. Ceslas Spicq, L’Épître aux Hébreux, (Paris: Libraire Lecoffee, 1952–53), 2:409-10; Jonathan I. Griffiths, Hebrews and Divine Speech, LNTS (London: T & T Clark, 2014), 143-44; B. F. Westcott, The Epistle to the Hebrews (London: Macmillan, 1892), 417; Harold W. Attridge, Hebrews, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1989), 377; James Moffatt, The Epistle to the Hebrews, ICC (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1924); Hugh Montefiore, A Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews, BNTC (London: A & C Black, 1964), 233; R. -

Of 9 the FAITH of MOSES Hebrews 11:23-28 Key Verses

THE FAITH OF MOSES Hebrews 11:23-28 Key Verses: 11:24,25 "By faith Moses, when he had grown up, refused to be known as the son of Pharaoh's daughter. He chose to be mistreated along with the people of God rather than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a short time." Moses is known as the most outstanding leader of all leaders who have lived in the world. Moses received the highest education in the palace of the Egyptian Empire for 40 years. For the growth of his inner character, he received another 40 years of humbleness training in the wilderness among seven daughters of Jethro, tending Jethro's flock of sheep. They call this humbleness training or the wilderness seminary. When Moses had completed 80 years of training altogether, God could use him greatly. In the Bible, Moses was known as a servant of God who worked harder than any others to lead his rebellious people; he died without seeing the promised land, though it had been his only dream to see it. There is a saying, "Moses dipped out all the water of a lake, then David caught all the fish and Solomon cooked and ate them all." But the author of Hebrews says that Moses is great because he had faith that pleases God. I. The faith of Moses' parents (23) First, they saw he was no ordinary child (23a). Read verse 23. "By faith Moses parents hid him for three months after he was born, because they saw he was no ordinary child, and they were not afraid of the king's Page 1 of 9 edict." Many great men in history were born in adverse circumstances or in tragic human conditions. -

Bliss – Analysis of Sacred Chronology.Pdf

Analysis of Sacred Chronology Sylvester Bliss With the Elements of Chronology; and the Numbers of the Hebrew Text Vindicated TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................3 CHRONOLOGY .............................................5 SACRED CHRONOLOGY .....................................42 APPENDIX .............................................227 INDEX ................................................229 PREFACE If Chronology is "the soul of history," it is equally so of prophecy. Without it, the Scriptures would lose much of their harmony and beauty. It is carefully interwoven into the sacred text, and gives the order and dependence of the several parts on each other. The chronology of the Bible is as important in its place as any other subject of revelation. When disregarded, sad errors have been made in locating the historical and prophetical Scriptures. The elements of Chronology, and the numerous scriptural synchronisms, have only been given in works too voluminous, diffusive and expensive for ordinary use. To place before those not having access to the larger works, the simple evidences by which scriptural events are located, is the design of the following pages. An original feature of this analysis of Scripture Chronology is the presenting in full, and in chronological order, the words of inspiration, which have a bearing on the time of the events and predictions therein recorded. The reader will thus be enabled to obtain a concise and clear, as well as a correct, understanding of the reasons which govern in the adoption of the several dates. The works of Prideaux, Hales, Usher, 4 Clark, Jackson, Blair, the Duke of Manchester, and others, have been freely consulted, in this compilation. To Dr. Hales in particular the author is much indebted for many valuable suggestions.