The Language of Superhero Mythology in Flash Gordon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROY THOMAS Chapter Four

Captain Marvel Jr. TM & © DC Comics DC © & TM Jr. Marvel Captain Introduction by ROY THOMAS Chapter Four Little Boy Blue Ed Herron had come to Fawcett with a successful track record of writing Explosive is the best way to describe this iconic, colorful cover (on opposite page) by and creating comic book characters that had gone on to greater popularity, Mac Raboy, whose renditions of a teen-age super-hero with a realistic physique was noth- including work on the earliest stories of Timely’s colorful Captain America— ing less than perfect. Captain Marvel Jr. #4, (Feb. 19, 1943). Inset bottom is Raboy’s first and his kid sidekick Bucky. It was during the fall of 1941 that Herron came cover for Fawcett and the first of the CMJr origin trilogy, Master Comics #21 (Dec. 1941). Below up with the idea of a new addition to the Fawcett family. With Captain is a vignette derived from Raboy’s cover art for Captain Marvel Jr. #26 (Jan. 1, 1945). Marvel sales increasing dramatically since his debut in February 1940, Fawcett management figured a teenage version of the “Big Red Cheese” would only increase their profits. Herron liked Raboy’s art very much, and wanted a more illustrative style for the new addition, as opposed to the C. C. Beck or Pete Costanza simplified approach on Captain Marvel. The new boy-hero was ably dubbed Captain Marvel Jr., and it was Mac Raboy who was given the job of visualizing him for the very first time. Jr.’s basic attire was blue, with a red cape. -

Digital Dialectics: the Paradox of Cinema in a Studio Without Walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , Vol

Scott McQuire, ‘Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , vol. 19, no. 3 (1999), pp. 379 – 397. This is an electronic, pre-publication version of an article published in Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television is available online at http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=g713423963~db=all. Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls Scott McQuire There’s a scene in Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis, Paramount Pictures; USA, 1994) which encapsulates the novel potential of the digital threshold. The scene itself is nothing spectacular. It involves neither exploding spaceships, marauding dinosaurs, nor even the apocalyptic destruction of a postmodern cityscape. Rather, it depends entirely on what has been made invisible within the image. The scene, in which actor Gary Sinise is shown in hospital after having his legs blown off in battle, is noteworthy partly because of the way that director Robert Zemeckis handles it. Sinise has been clearly established as a full-bodied character in earlier scenes. When we first see him in hospital, he is seated on a bed with the stumps of his legs resting at its edge. The assumption made by most spectators, whether consciously or unconsciously, is that the shot is tricked up; that Sinise’s legs are hidden beneath the bed, concealed by a hole cut through the mattress. This would follow a long line of film practice in faking amputations, inaugurated by the famous stop-motion beheading in the Edison Company’s Death of Mary Queen of Scots (aka The Execution of Mary Stuart, Thomas A. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

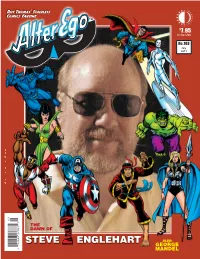

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

Blade II" (Luke Goss), the Reapers Feed Quickly

J.antie Lissow- knocks Starbucks, offers funny anecdotes By Jessica Besack has been steadily rising. stuff. If you take out a whole said, you might find "Daddy's bright !)ink T -shirt with the Staff Writer He is now signed under the shelf, it will only cost you $20." Little Princess" upon closer sparkly words "Daddy's Little Gersh Agency, which handles Starbucks' coffee was another reading. Princess" emblazoned across the Comedian Jamie Lissow other comics such as Dave object of Lissow's humor. He In conclusion to his routine, front. entertained a small audience in Chappele, Jim Breuer and The warned the audience to be cau Lissow removed his hooded You can read more about the Wolves' Den this past Friday Kids in the Hall. tious when ordering coffee there, sweatshirt to reveal a muscular Jamie Lissow at evening joking about Starbucks Lissow amused the audience since he has experienced torso bulging out of a tight, http://www.jamielissow.com. coffee, workout buffs, dollar with anecdotes of his experi mishaps in the process. stores and The University itself. ences while touring other col "I once asked 'Could I get a Lissow, who has appeared on leges during the past few weeks. triple caramel frappuccino "The Tonight Show with Jay At one college, he performed pocus-mocha?"' Lissow said, Leno" and NBC's "Late Friday," on a stage with no microphone "and the coffee lady turned into a opened his act with a comment after an awkward introduction, newt. I think I said it wrong." about the size of the audience, only to notice that halfway Lissow asked audience what saying that when he booked The through his act, students began the popular bars were for University show, he presented approaching the stage carrying University students. -

System Safety Engineering: Back to the Future

System Safety Engineering: Back To The Future Nancy G. Leveson Aeronautics and Astronautics Massachusetts Institute of Technology c Copyright by the author June 2002. All rights reserved. Copying without fee is permitted provided that the copies are not made or distributed for direct commercial advantage and provided that credit to the source is given. Abstracting with credit is permitted. i We pretend that technology, our technology, is something of a life force, a will, and a thrust of its own, on which we can blame all, with which we can explain all, and in the end by means of which we can excuse ourselves. — T. Cuyler Young ManinNature DEDICATION: To all the great engineers who taught me system safety engineering, particularly Grady Lee who believed in me, and to C.O. Miller who started us all down this path. Also to Jens Rasmussen, whose pioneering work in Europe on applying systems thinking to engineering for safety, in parallel with the system safety movement in the United States, started a revolution. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: The research that resulted in this book was partially supported by research grants from the NSF ITR program, the NASA Ames Design For Safety (Engineering for Complex Systems) program, the NASA Human-Centered Computing, and the NASA Langley System Archi- tecture Program (Dave Eckhart). program. Preface I began my adventure in system safety after completing graduate studies in computer science and joining the faculty of a computer science department. In the first week at my new job, I received a call from Marion Moon, a system safety engineer at what was then Ground Systems Division of Hughes Aircraft Company. -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

Super Ticket Student Edition.Pdf

THE NATION’S NEWSPAPER Math TODAY™ Student Edition Super Ticket Sales Focus Questions: h What are the values of the mean, median, and mode for opening weekend ticket sales and total ticket sales of this group of Super ticket sales movies? Marvel Studio’s Avi Arad is on a hot streak, having pro- duced six consecutive No. 1 hits at the box office. h For each data set, determine the difference between the mean and Blade (1998) median values. Opening Total ticket $17.1 $70.1 weekend sales X-Men (2000) (in millions) h How do opening weekend ticket $54.5 $157.3 sales compare as a percent of Blade 2 (2002) total ticket sales? $32.5 $81.7 Spider-Man (2002) $114.8 $403.7 Daredevil (2003) $45 $102.2 X2: X-Men United (2003) 1 $85.6 $200.3 1 – Still in theaters Source: Nielsen EDI By Julie Snider, USA TODAY Activity Overview: In this activity, you will create two box and whisker plots of the data in the USA TODAY Snapshot® "Super ticket sales." You will calculate mean, median and mode values for both sets of data. You will then compare the two sets of data by analyzing the differences graphically in the box and whisker plots, and numerically as percents of ticket sales. ©COPYRIGHT 2004 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co., Inc. This activity was created for use with Texas Instruments handheld technology. MATH TODAY STUDENT EDITION Super Ticket Sales Conquering comic heroes LIFE SECTION - FRIDAY - APRIL 26, 2002 - PAGE 1D By Susan Wloszczyna USA TODAY Behind nearly every timeless comic- Man comic books the way an English generations weaned on cowls and book hero, there's a deceptively unas- scholar loves Macbeth," he confess- capes. -

AIR FORCE Magazine / July 2007 42

A Brush With the Air Force 42 AIR FORCE Magazine / July 2007 prototype for Corkin was Air Force Col. Milton Caniff was out front with “Terry and Philip Cochran, a noted World War II pilot and leader of air commandos in the Pirates,” but other cartoonists also found Burma. (See “The All-American Air- their calling in the wild blue yonder. man,” March 2000, p. 52.) He became a continuing character in “Terry.” In a famous “Terry and the Pirates” Sunday page from 1943, Corkin opened with, “Let’s take a walk, Terry,” and then delivered an inspirational talk about A Brush With the war and the Air Force as he and the newly fledged pilot Terry strolled around the flight line. The page was “read” into the Congressional Record and reported in the newspapers. Terry, Flip, and their colleagues had a great following among airmen, and the Air Force By John T. Correll the strip had considerable morale and public relations value. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Forces, assigned an officer to as- sist Caniff with any technical details he needed. Caniff produced another strip, “Male Call,” without charge for camp and base newspapers. It featured Miss Lace, who was reminiscent of the Dragon Lady but less standoffish. It is difficult today to comprehend what a big deal the funnies used to be. Everybody read the comic strips. Characters were as well known as movie stars. The strips were printed much larger than present comic strips are. On Sunday, a popular strip might get a whole color page to itself. -

The Panama Canal Review Is Published Twice a Year

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES m.• #.«, I i PANAMA w^ p IE I -.a. '. ±*L. (Qfx m Uu *£*£ - Willie K Friar David S. Parker Editor, English Edition Governor-President Jose T. Tunon Charles I. McGinnis Editor, Spanish Edition Lieutenant Governor Writers Eunice Richard, Frank A. Baldwin Fannie P. Hernandez, Publication Franklin Castrellon and Dolores E. Suisman Panama Canal Information Officer Official Panama Canal the Review will be appreciated. Review articles may be reprinted without further clearance. Credit tu regular mail airmail $2, single copies 50 cents. The Panama Canal Review is published twice a year. Yearly subscription: $1, Canal Company, to Panama Canal Review, Box M, Balboa Heights, C.Z. For subscription, send check or money order, made payable to the Panama Editorial Office is located in Room 100, Administration Building, Balboa Heights, C.Z. Printed at the Panama Canal Printing Plant, La Boca, C.Z. Contents Our Cover The Golden Huacas of Panama 3 Huaca fanciers will find their favor- the symbolic characters of Treasures of a forgotten ites among the warrior, rainbow, condor god, eagle people arouse the curiosity and alligator in this display of Pan- archeologists around the of ama's famous golden artifacts. world. The huacas, copied from those recov- Snoopy Speaks Spanish 8 ered from the graves of pre-Columbian loaned to The In the phonetics of the fun- Carib Indians, were Review by Neville Harte. The well nies, a Spanish-speaking dog known local archeologist also provided doesn't say "bow wow." much of the information for the article Balseria 11 from his unrivaled knowledge of the Broken legs are the name of subject—the fruit of a 26-year-long love affair with the huaca, and the country the game when the Guaymis and people of Panama, past and present. -

Kiddie Rides

Kiddie Rides Kiddie Rides offered a largely untapped market after World War II. Realizing the trend, in 1950, Whitney moved his small assortment to the space left by the removal of the Shoot the Chutes and the Tumble Bug on Balboa off the Great Highway. These flat rides were cheap to install Figure 1 - The boat rides were a kid favorite. They were Figure 2 - Kids favored the speed boats. No sail and Figure 3 - . and they also provided a great photo slow, safe and seemed to do something. Image courtesy of you know they went faster. Image courtesy of Steve opportunity to show off your finest. Image courtesy of Ian Samuels Faulkner Playland-Not-at-the-Beach and created that new draw he wanted. They remained there until select rides relocated to Fun-Tier Town in 1960. Figure 1 - This cowboy is ready for another ride. Image courtesy of Dennis O'Rorke Figure 6 (Right) - Guaranteed to stay on track, there was an assortment of vehicles to choose from. Image courtesy of Steve Faulkner Figure 4- Bubbles the Whale was a fun up & down ride. He made the cut to Fun-Tier Town. Image courtesy of Steve Faulkner Figure 7– A young Gary David learns this is serious business and required Figure 8 - This young man is having the time of his life. Really! Image intense concentration. Image courtesy of Heather David courtesy of Playland-Not-at-the-Beach Figure 9 - The Kiddie Coaster actually Offered some thrills. It was comparatively fast and had some decent banks and turns. -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas.