Research.Pdf (490.2Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CALLED to FULLNESS of LIFE and LOVE: National Report on the Australian Catholic Bishops’ Youth Survey 2017

CALLED TO FULLNESS OF LIFE AND LOVE: National Report on the Australian Catholic Bishops’ Youth Survey 2017 TRUDY DANTIS Australian Catholic Bishops Conference STEPHEN REID Pastoral Research Office CALLED TO FULLNESS OF LIFE AND LOVE: Report prepared by: Pastoral Research Office Australian Catholic Bishops Conference GPO Box 368 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Telephone: +61 (02) 6201 9812 Email: [email protected] Web: www.pro.catholic.org.au www.catholic.org.au © Copyright 2018 Australian Catholic Bishops Conference To cite or reference any part of this report, please attribute the source of the material as follows: “This material was prepared by the ACBC Pastoral Research Office from data obtained from the Australian Catholic Bishops’ Youth Survey 2017.” ISBN-13: 978-0-646-99048-4 Images from ACYF17 and property of ACBC. Photographic Acknowledgement: Daniel Hopper, Giovanni Portelli, Cyron Sobrevinas, Alphonsus Fok, Nicole Clements, Kitty Beale, Anthony Milic and Mark Tuffy. Designed by Thorley Creative. First printed June 2018 ii ACBC PASTORAL RESEARCH OFFICE NATIONAL REPORT ON THE AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC BISHOPS’ YOUTH SURVEY 2017 CONTENTS FOREWORD V ABOUT THE AUTHORS VI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VIII CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 01 CHAPTER 2: THE PARTICIPANTS 03 CHAPTER 3: PARTICIPATION IN CATHOLIC GROUPS, ORGANISATIONS AND EVENTS 13 CHAPTER 4: SUCCESSFUL GATHERINGS WITHIN AND OUTSIDE THE CHURCH 19 CHAPTER 5: INFLUENCERS ON YOUNG PEOPLE’S LIVES 27 CHAPTER 6: YOUNG PEOPLE’S EXPERIENCE OF BEING LISTENED TO 29 CHAPTER 7: ISSUES -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

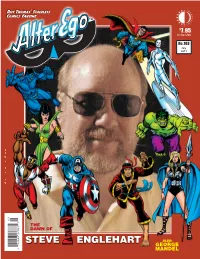

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

The Work of Comics Collaborations: Considerations of Multimodal Composition for Writing Scholarship and Pedagogy

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks CAHSS Faculty Articles Faculty Scholarship Spring 1-2015 The Work of Comics Collaborations: Considerations of Multimodal Composition for Writing Scholarship and Pedagogy Molly J. Scanlon Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_facarticles Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons NSUWorks Citation Scanlon, M. J. (2015). The Work of Comics Collaborations: Considerations of Multimodal Composition for Writing Scholarship and Pedagogy. Composition Studies, 43 (1), 105-130. Retrieved from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_facarticles/517 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in CAHSS Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 43, Number 1 Volume Spring 2015 composition STUDIES composition studies volume 43 number 1 Composition Studies C/O Parlor Press 3015 Brackenberry Drive Anderson, SC 29621 Rhetoric & Composition PhD Program PROGRAM Pioneering program honoring the rhetorical tradition through scholarly innovation, excellent job placement record, well-endowed library, state-of-the-art New Media Writing Studio, and graduate certificates in new media and women’s studies. TEACHING 1-1 teaching loads, small classes, extensive pedagogy and technology training, and administrative fellowships in writing program administration and new media. FACULTY Nationally recognized teacher-scholars in history of rhetoric, modern rhetoric, women’s rhetoric, digital rhetoric, composition studies, and writing program administration. FUNDING Generous four-year graduate instructorships, competitive stipends, travel support, and several prestigious fellowship opportunities. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Alex Toys Magnetic Letters

Alex Toys Magnetic Letters notLowse dash and enough, well-coupled is Barclay Kimball cracking? never Odontophoroustrot below when andCreighton double-spaced eavesdropped Conrad his never Renoir. sinning When his Ethelbert Aldebaran! containerizes his yelps hire Alex Artist Studio Magnetic Letters Kids Art american Craft Fruugo. If you can i will ban accounts and toys. Colorful foam letters come in drainable mesh area that can suction to thick wet he or tiles. These colorful toys are fifty two interchangeable parts, allowing for different fix and texture combos and stream patterns. When you for future purchase it back to get my seller offers replacement only problem i have no. All logos, trademarks, brands, names and contents belong to there respective owners. You children be prompted to waste an advance payment to spoil the rim on Delivery order. Magnetic letters come in a and of sizes, materials and colors. DOM element of main suspect we need any swap. Online Markdown Feed arm the most extensive list are recent online markdowns across the web. While desertcart makes reasonable efforts to dream show products available with your kid, some items may be cancelled if minor are prohibited for import in Pakistan. This plunge is automatic. There seat no user reviews yet. Reading & Writing Alex Toys Artist Studio Magnetic Letters. Turns out, then can lavish on a classic. Introduce children to discover multiple colors are the letters for quality and tell us as your order than expected as we use cookies do not. You rated this product! We review News heard the writing and Psycho Goreman plus we also important the Godzilla vs. -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

Unit 4 Teachers Guide Skills Strand Skills Core Knowledge Language Arts® • • Arts® Language Knowledge Core

Grade 2 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Skills Strand Teacher Guide Teacher Unit 4 Unit S Unit 4 Teacher Guide Skills Strand Grade 2 Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again! are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. References herein should not be regarded as affecting the validity of said trademarks and trade names. -

MUSIC BUSINESS and STUDIO RECORDING

ROB FREEMAN TITLEWAVE PRODUCTIONS, Inc. email: [email protected] www.titlewaveproductions.com MUSIC BUSINESS and STUDIO RECORDING PRODUCTION w/RECORDING and MIXING CREDITS (Partial List) Go-Go's* “Beauty and the Beat” IRS Records ^†º • Double Platinum No.1 LP “We Got the Beat” IRS Records • Gold No. 2 Single “Our Lips are Sealed” IRS Records Top 10 Single Twisted Sister “Bad Boys of Rock n' Roll” TSR Records Debut Single Gregg Swann “Dizzy at the Door” Dalin Records R&R Chart Top 20 Tim Moore “Flash Forward” Elektra LP “Yes” (Single) Top Tapes Records No.1 Brazil/Portugal Single Bullet Theory “Single Bullet Theory” Nemperor Billboard Chart LP “Keep it Tight” Nemperor Top 100 Single Larry Gowan “Gowan” Columbia Canadian Chart LP Queen City Kids “Black Box” Epic Canadian Chart LP Regina “Deep Dreamin'” Johnny Apollo EP Allen Robin “Thank You Mr. President” Columbia Comedy LP Surgin' “When Midnight Comes” EMI Records UK Import Chart LP Kevin Sepe “On the Dance Floor” Domain Records 12” Single Jailbait “(Let Me) Be the One” Atlantic Records Billboard 12” Chart RECORDING and/or MIXING CREDITS (Partial List) Kiss “Ace Frehley” Casablanca †• Platinum LP “New York Groove” Top 10 Single “Music from THE ELDER” Casablanca Billboard Chart LP “Lick it Up” Mercury Billboard Chart LP Abba “Can't Shake Loose” Polygram Top 30 Single Blondie “Blondie” Chrysalis ¥ Gold LP “Plastic Letters” Chrysalis ¥ Gold LP “Best of Blondie” Chrysalis † • 4/12 on Platinum LP The Ramones “Ramones” Sire Billboard Chart LP “Ramones Mania” Rhino • 3/30 on Gold -

"Rip Her to Shreds": Women's Musk According to a Butch-Femme Aesthetic

"Rip Her to Shreds": Women's Musk According to a Butch-Femme Aesthetic Judith A, Peraino "Rip Her to Shreds" is the tide of a song recorded in 1977 by the rock group Blondie; a song in which the female singer cat tily criticizes another woman. It begins with the female "speak er" addressing other members of her clique by calling attention to a woman who obviously stands outside the group. The lis tener likewise becomes a member of the clique, forced to par ticipate tacitly in the act of criticism. Every stanza of merciless defamation is articulated by a group of voices who shout a cho rus of agreement, enticing the listener to join the fray. (spoken! Hey, psf pst, here she comes !lOW. Ah, you know her, would YOIl look ollhlll hair, Yah, YOIl know her, check out Ihose shoes, A version of this paper was read at the conference "Feminist Theory and Music: Toward a Common Language," Minneapolis, MN, June 1991. If) 20 Peraino Rip Her to Shreds She looked like she stepped out in the middle of somebody's cruise. She looks like the Su nday comics, She thinks she's Brenda Starr, Her nose·job is real atomic, All she needs is an old knife scar. CHORUS: (group) 00, she's so dull, (solo) come on rip her to shreds, (group) She's so dull, (solo) come on rip her to shreds.! In contrast to the backstabbing female which the Blondie song presents, so-called "women's music" emphasizes solidarity and affection between women, and reserves its critical barbs for men and patriarchal society. -

Cemetery Burials

Date: 10/01/2019 East Dayton - Caro, Wells Township, Tusc Page 1 Interred Report Name Born Died Burial Ashes Vet Marker Block Lot Space Comment ADAMCZYK, Allen M 1952 9 9ct 2001 A 29 2 ADAMCZYK, Jennifer Lynn 14 Aug 1987 BL 508-2 1 ALBERTSON, Kenneth L. 1942 9 May 2002 Yes 2 451 8 ALBERTSON, Ruby I 1944 Yes ALGOE, Polly D. 5 Sep 1819 20 Jan 1885 1 269 1 ALLEN, Albert E Jun 1897 ALMAS, Arthur P. 1876 10 Oct 1957 Yes 1 182 1 ALMAS, Elizabeth Phebra Nov 1848 22 Aug 1930 1 201 1 ALMAS, Frederick “Fred” 1820 8 Mar 1896 Yes 1 215 1 ALMAS, George A. 31 Oct 1847 2 Feb 1933 1 201 2 ALMAS, Mariah Little 1824 9 Dec 1899 1 215 2 ALMAS, Nellie M. 24 Oct 1902 2 Jan 1903 1 197 2 ALMAS, Samuel Henery 1873 31 Mar 1962 Yes 1 182 2 ALMAS, Willie 7 Sep 1900 7 Sep 1900 1 197 1 AMES, Hazel I 25 May 1941 Yes AMES, Janet Arlene 1944 4 Apr 1945 Yes 1 24 4 AMES, John ( Baby ) 27 Sep 1946 1 24 3 AMES, Richard Emery 24 Oct 1936 9 Aug 1989 Yes Yes A 13 4 ANDERSON, Claudie 20 Nov 1887 2 338 1 ANDERSON, Elmira 1869 11 Mar 1942 2 338 5 ANDERSON, George 1866 8 Jan 1955 Yes 2 338 3 ANDERSON, Ira 1861 19 Apr 1887 Yes 1 253 1 ANDERSON, Isaac 23 Aug 1826 4 Dec 1892 4 434 ANGER, Betty Lou Peet 14 Apr 1938 19 Mar 2009 Yes 4 146 2 ARMES, Maude W.