On Taking Liberty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Australian Mirage

An Australian Mirage Author Hoyte, Catherine Published 2004 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1870 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367545 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au AN AUSTRALIAN MIRAGE by Catherine Ann Hoyte BA(Hons.) This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Griffith University Faculty of Arts School of Arts, Media and Culture August 2003 Statement of Authorship This work has never been previously submitted for a degree or diploma in any university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this dissertation contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the dissertation itself. Abstract This thesis contains a detailed academic analysis of the complete rise and fall of Christopher Skase and his Qintex group mirage. It uses David Harvey’s ‘Condition of Postmodernity’ to locate the collapse within the Australian political economic context of the period (1974-1989). It does so in order to answer questions about why and how the mirage developed, why and how it failed, and why Skase became the scapegoat for the Australian corporate excesses of the 1980s. I take a multi-disciplinary approach and consider corporate collapse, corporate regulation and the role of accounting, and corporate deviance. Acknowledgments I am very grateful to my principal supervisor, Dr Anthony B. van Fossen, for his inspiration, advice, direction, guidance, and unfailing encouragement throughout the course of this study; and for suggesting Qintex as a case study. -

Offshore-October-November-2005.Pdf

THE MAGAZ IN E OF THE CRUIS IN G YACHT CLUB OF AUSTRALIA I OFFSHORE OCTOBER/ NOVEMB rn 2005 YACHTING I AUSTRALIA FIVE SUPER R MAXIS ERIES FOR BIG RACE New boats lining up for Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race HAMILTON ISLAND& HOG'S BREATH Northern regattas action t\/OLVO OCEAN RACE Aussie entry gets ready for departure The impeccable craftsmanship of Bentley Sydney's Trim and Woodwork Special ists is not solely exclusive to motor vehicles. Experience the refinement of leather or individually matched fine wood veneer trim in your yacht or cruiser. Fit your pride and joy with premium grade hide interiors in a range of colours. Choose from an extensive selection of wood veneer trims. Enjoy the luxury of Lambswool rugs, hide trimmed steering wheels, and fluted seats with piped edging, designed for style and unparalleled comfort. It's sea-faring in classic Bentley style. For further details on interior styling and craftsmanship BENTLEY contact Ken Boxall on 02 9744 51 I I. SYDNEY contents Oct/Nov 2005 IMAGES 8 FIRSTTHOUGHT Photographer Andrea Francolini's view of Sydney 38 Shining Sea framed by a crystal tube as it competes in the Hamilton Island Hahn Premium Race Week. 73 LAST THOUGHT Speed, spray and a tropical island astern. VIEWPOINT 10 ATTHE HELM CYCA Commodore Geoff Lavis recounts the many recent successes of CYCA members. 12 DOWN THE RHUMBLINE Peter Campbell reports on sponsorship and media coverage for the Rolex Sydney H obart Yacht Race. RACES & REGATTAS 13 MAGIC DRAGON TAKES GOLD A small boat, well sailed, won out against bigger boats to take victory in the 20th anniversary Gold Coast Yacht Race. -

Cyaa Newsletter

www.classic‑yacht.asn.au Issue 26 – December 2008 – Classic Yacht Association of Australia Magazine CONTENTS CYAA REPRESENTATIVES 2 COMING EVENTS 2 THE CUP REGATTA 2008 3 THE NEW ZEALAND CLASSIC YACHT JOURNAL 6 CROSS TASMAN EXPORTS 10 LAURABADA - ONE MAN’S DREAM 11 HUON PINE WOODEN BOATS - A TASMANIAN TRADITION A REAL TREASURE HAS BEEN SAVED 15 WINDWARD II 17 GAFFERS DAY SYDNEY HARBOUR 19 VANITY TO TASMANIA 22 MIKE HURRELL SHIPWRIGHTS 26 RACING CLASSIC YACHTS 28 FANCY A CRUISE TO ATTEND THE QUEENSCLIFF MARITIME WEEKEND: 20-22 FEB 2009? 30 NEW MEMBERS 31 RELUCTANT SALE 31 MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION 32 Our aim is to promote the appreciation and participation of sailing classic yachts in Australia, and help preserve the historical and cultural significance of these unique vessels. Classic Yacht Association of Australia CYAA REPRESENTATIVES COMING EVENTS AUSTRALIAN WOODEN Boat Festival ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER Hobart, Tasmania 6-9 February 2009 CYAA Officer 343 Ferrars St www.australianwoodenboatfestival.com.au Albert Park AUCKLAND CLASSIC YACHT Regatta Victoria 3206 Auckland, New Zealand admin@classic‑yacht.asn.au 13-15 February 2009 EDITORIAL www.classicyacht.org.nz/news.php Roger Dundas QUEENSCLIFF MARITIME WEEKEND Mobile 0419 342 144 Queenscliff, Victoria [email protected] 20-22 February 2009 Design and Production Blueboat SOUTH AUSTRALIAN WOODEN Boat & MUSIC Festival 7-9 March 2009 www.blueboat.com.au River Port of Goolwa, South Australia Ph (08) 8555 7240 or email [email protected] NEW SOUTH WALES Philip Kinsella Tel (02) 9498 2481 [email protected] QUEENSLAND EDITORS REQUEST Ivan Holm Tel (07) 3207 6722, Mobile 0407 128 715 As foredeck crew [email protected] on the Tumlaren SOUTH AUSTRALIA “Zephyr” the duties Tony Kearney of sailing and the Mobile 0408 232 740 mistress on the [email protected] helm do not always allow me to take advantage of the photo opportunities that TASMANIA Classic sailing provides. -

Events Plan Ahead with Our Big Listings Guide

JAN 20 - FEB 3 2016 200+ Events www.getintonewcastle.co.uk Plan ahead with our big listings guide NEW Big LOOK! eat It’s back! Eat for just £10pp and INSIDE £15pp during the biggest-ever NE1 Newcastle Restaurant Week Reeves and Mortimer Heading for a big night out Rambert Dance Co They’re the greatest dancers... Hit the gym Twinkle toes Go on, you know you want to! Strictly Come Dancing Live Tour hits Newcastle FREE NE1 magazine is brought to you by NE1 Ltd, the company which champions all that’s great about Newcastle city centre Restaurant Week 12Come dining NE1’s Newcastle Restaurant Contents Week is back January 18-24 18th-24th January What’s #NE1RestaurantWeek on in NE1 04 Going out? It’s all here - Arenacross, Burns Night, an Eagle about town and much more 11 New you Step away from the sofa people - this is your guide to getting in shape in NE1 14 Music Bowling for Soup, Alexander Armstrong and the mighty Temple of Rock 16 Keeeeep dancing Strictly Come Dancing hits town 20 Shooting Stars One Vic and Bob’s 25 years of silliness Week, 22 Listings 80+ Restaurants, Your go-to guide to NE1 goings-on Bonbar pp* or 15 10 £ ©Offstone Publishing 2016. All rights Publishers: Jane Pikett, Gary Ramsay £ reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced without the written permission Writers: Dean Bailey, Claire Dupree of the publisher. All information contained (listings editor) in this magazine is as far as we are aware, Designers: Stuart Blackie If you wish to submit a listing for inclusion correct at the time of going to press. -

1. Gina Rinehart 2. Anthony Pratt & Family • 3. Harry Triguboff

1. Gina Rinehart $14.02billion from Resources Chairman – Hancock Prospecting Residence: Perth Wealth last year: $20.01b Rank last year: 1 A plunging iron ore price has made a big dent in Gina Rinehart’s wealth. But so vast are her mining assets that Rinehart, chairman of Hancock Prospecting, maintains her position as Australia’s richest person in 2015. Work is continuing on her $10billion Roy Hill project in Western Australia, although it has been hit by doubts over its short-term viability given falling commodity prices and safety issues. Rinehart is pressing ahead and expects the first shipment late in 2015. Most of her wealth comes from huge royalty cheques from Rio Tinto, which mines vast swaths of tenements pegged by Rinehart’s late father, Lang Hancock, in the 1950s and 1960s. Rinehart's wealth has been subject to a long running family dispute with a court ruling in May that eldest daughter Bianca should become head of the $5b family trust. 2. Anthony Pratt & Family $10.76billion from manufacturing and investment Executive Chairman – Visy Residence: Melbourne Wealth last year: $7.6billion Rank last year: 2 Anthony Pratt’s bet on a recovering United States economy is paying off. The value of his US-based Pratt Industries has surged this year thanks to an improving manufacturing sector and a lower Australian dollar. Pratt is also executive chairman of box maker and recycling business Visy, based in Melbourne. Visy is Australia’s largest private company by revenue and the biggest Australian-owned employer in the US. Pratt inherited the Visy leadership from his late father Richard in 2009, though the firm’s ownership is shared with sisters Heloise Waislitz and Fiona Geminder. -

The Private Lives of Australian Cricket Stars: a Study of Newspaper Coverage 1945- 2010

Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS The Private Lives of Australian Cricket Stars: a Study of Newspaper Coverage 1945- 2010 Patching, Roger Award date: 2014 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS The Private Lives of Australian Cricket Stars: a Study of Newspaper Coverage 1945- 2010 Patching, Roger Award date: 2014 Awarding institution: Bond University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

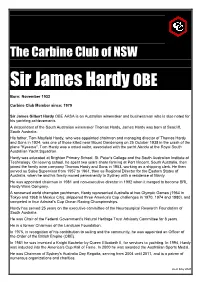

Sir James Hardy OBE

The Carbine Club of NSW Sir James Hardy OBE Born: November 1932 Carbine Club Member since: 1979 Sir James Gilbert Hardy OBE AASA is an Australian winemaker and businessman who is also noted for his yachting achievements. A descendant of the South Australian winemaker Thomas Hardy, James Hardy was born at Seacliff, South Australia. His father, Tom Mayfield Hardy, who was appointed chairman and managing director of Thomas Hardy and Sons in 1924, was one of those killed near Mount Dandenong on 25 October 1938 in the crash of the plane "Kyeema". Tom Hardy was a noted sailor, associated with the yacht Nerida at the Royal South Australian Yacht Squadron. Hardy was educated at Brighton Primary School, St. Peter's College and the South Australian Institute of Technology. On leaving school, he spent two years share farming at Port Vincent, South Australia, then joined the family wine company Thomas Hardy and Sons in 1953, working as a shipping clerk. He then served as Sales Supervisor from 1957 to 1961, then as Regional Director for the Eastern States of Australia, when he and his family moved permanently to Sydney with a residence at Manly. He was appointed chairman in 1981 and non-executive director in 1992 when it merged to become BRL Hardy Wine Company. A renowned world champion yachtsman, Hardy represented Australia at two Olympic Games (1964 in Tokyo and 1968 in Mexico City), skippered three America's Cup challenges in 1970, 1974 and 1980), and competed in four Admiral's Cup Ocean Racing Championships. Hardy has served 25 years on the executive committee of the Neurosurgical Research Foundation of South Australia. -

The International Flying Dutchman Class Book

THE INTERNATIONAL FLYING DUTCHMAN CLASS BOOK www.sailfd.org 1 2 Preface and acknowledgements for the “FLYING DUTCHMAN CLASS BOOK” by Alberto Barenghi, IFDCO President The Class Book is a basic and elegant instrument to show and testify the FD history, the Class life and all the people who have contributed to the development and the promotion of the “ultimate sailing dinghy”. Its contents show the development, charm and beauty of FD sailing; with a review of events, trophies, results and the role past champions . Included are the IFDCO Foundation Rules and its byelaws which describe how the structure of the Class operate . Moreover, 2002 was the 50th Anniversary of the FD birth: 50 years of technical deve- lopment, success and fame all over the world and of Class life is a particular event. This new edition of the Class Book is a good chance to celebrate the jubilee, to represent the FD evolution and the future prospects in the third millennium. The Class Book intends to charm and induce us to know and to be involved in the Class life. Please, let me assent to remember and to express my admiration for Conrad Gulcher: if we sail, love FD and enjoyed for more than 50 years, it is because Conrad conceived such a wonderful dinghy and realized his dream, launching FD in 1952. Conrad, looked to the future with an excellent far-sightedness, conceived a “high-perfor- mance dinghy”, which still represents a model of technologic development, fashionable 3 water-line, low minimum hull weight and performance . Conrad ‘s approach to a continuing development of FD, with regard to materials, fitting and rigging evolution, was basic for the FD success. -

5 December 2008 Volume: 18 Issue: 24 Secret Life of a Bullied Writer Andrew Hamilton

5 December 2008 Volume: 18 Issue: 24 Secret life of a bullied writer Andrew Hamilton .........................................1 Australia shamed as climate reaches turning point Tony Kevin .............................................4 Thai airport protesters’ victory short-lived Nicholas Farrelly and Andrew Walker ...........................7 Good Aussie films a thing of the past Ruby Hamad ............................................9 Workers’ solution for fallen childcare empire Cameron Durnsford ...................................... 11 The sinking of WA Inc. Mark Skulley ........................................... 13 The nun and the burqa Bronwyn Lay ........................................... 16 Big rat poems Christopher Kelen ....................................... 19 Neoliberal termites unbalance Fair Work Bill Tim Battin ............................................. 23 Fashion fix won’t mend failed states Michael Mullins ......................................... 25 Poor man’s pioneer Andrew Hamilton ........................................ 27 Chipping away at Australia’s frozen heart Cassandra Golds ........................................ 30 Truth the first casualty of war film Tim Kroenert ........................................... 32 Imagination spent on global financial solutions Colin Long ............................................. 34 Theological colleges on shaky ground Neil Ormerod ........................................... 37 Train story Gillian Bouras .......................................... 39 Cheap retail at -

Did You Know Flying Dutchman Class/Ben Lexcen/Bob Miller

DID YOU KNOW The late Ben Lexcen designer of the famous “winged keel” on “Australia II,” was an RQYS Member from 1961 to 1968. When skippered by John Bertrand in 1983, “Australia II” became the first non - American yacht to win the America’s Cup in its then 132 year history. Bill Kirby FLYING DUTCHMAN CLASS/BEN LEXCEN/BOB MILLER In 1958, the Royal Queensland Yacht Club introduced the International Flying Dutchman Olympic Class two - man dinghy into its fleet. Commodore the late John H “Jock” Robinson announced in his Annual Report for the year that the striking of a levy to assist Australian Olympic Yachting at the 1964 Games at Naples had been approved unanimously. The 1961 – 1962 Australian Champions in the International Flying Dutchman Class were Squadron Members Craig Whitworth, skipper and Bob Miller, forward hand sailing in the “AS Huybers.” The boat was made available for Craig and Bob to sail via efforts of the late Past Commodore Alf Huybers, a well - known businessman of the time in Brisbane and proprietor of Queensland Pastoral Supplies. I was told recently by Bill Wright of Norman R Wright & Sons that Bob Miller was apprenticed as a Sailmaker to his Uncle, Norman J Wright, at the Florite sail loft run by George Manders and seamstress Mrs Lauman. Norman J Wright taught Bob Miller basic yacht design and they teamed up to design the first 3 Man 18 foot skiff “Taipan.” That was closely followed by the World Champion 18 Footer, “Venom” and I was also told by Bill the rig plan of “Taipan” and “Venom” closely followed that of a Flying Dutchman. -

Spring 2017 Newcastle Cruising Yacht Club

Marine Rescue 14 17 Land Rover Sydney to Gold Coast 19 Inaugural She Sails Regatta 24 spring 17 Newcastle Cruising Yacht Club • 95 Hannell Street Wickham NSW 2293 • Ph 02 4940 8188 • www.ncyc.net.au SPRING 2017 NEWCASTLE CRUISING YACHT CLUB Unwind | Share | Laugh | Enjoy In this issue Spring 2017 journal A quarterly publication EVERY ISSUE Commodore's Report ..................................................... 4 12 Rear Commodore’s Report ............................................ 5 Presentation Night CEO Report .................................................................... 6 Marina & Assets Manager’s Report ............................... 7 Our Club......................................................................... 8 16 Social Highlights .......................................................... 11 Laser Sailing ................................................................ 16 Club Sailing ................................................................. 18 Where in the World was our Burgee ............................ 26 Borrelli Quirk Newcastle Real Estate .......................... 28 Australia II Replica Yacht ESSENTIAL INFORMATION Security Phone Numbers .............................................. 27 Coming Events ............................................................. 27 FEATURE ARTICLES Tenacity Award............................................................... 9 Founders Day Celebrations .......................................... 10 20 Marine Rescue ............................................................ -

Shropshire Cover October 2017 .Qxp Shropshire Cover 22/09/2017 14:36 Page 1

Shropshire Cover October 2017 .qxp_Shropshire Cover 22/09/2017 14:36 Page 1 ED GAMBLE AT Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands HENRY TUDOR HOUSE SHROPSHIRE WHAT’S ON OCTOBER 2017 ON OCTOBER WHAT’S SHROPSHIRE Shropshire ISSUE 382 OCTOBER 2017 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On shropshirewhatson.co.uk PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide stepAUSTENTATIOUS back in time at Theatre Severn TWITTER: @WHATSONSHROPS TWITTER: heavenlyMEGSON music and northern humour at The Hive FACEBOOK: @WHATSONSHROPSHIRE GhostlySPOOK-TASTIC! Gaslight returns to Blists Hill Victorian Town SHROPSHIREWHATSON.CO.UK Day of the Friday 10th November The Buttermarket, Shrewsbury tickets available at Dead thebuttermarket.co.uk Niko's F/P October 2017.qxp_Layout 1 25/09/2017 10:44 Page 1 Contents October Shrops.qxp_Layout 1 22/09/2017 12:23 Page 2 October 2017 Contents Disney On Ice - grab your passport for one big adventure at Genting Arena - more on page 45 Carrie Hope Fletcher Matt Lucas Awful Auntie the list talks about being part of talks about life, from Little David Walliams’ much-loved Your 16-page The Addams Family... Britain to Little Me story arrives on stage week-by-week listings guide feature page 8 interview page 19 page 30 page 53 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 15. Music 20. Comedy 24. Theatre 39. Film 42. Visual Arts 44. Events @whatsonwolves @whatsonstaffs @whatsonshrops Wolverhampton What’s On Magazine Staffordshire What’s