The Roadhouses of the Richardson Highway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Native Plant Species of the Fairbanks Region 2005 - 2006 Surveys

Non-Native Plant Species of the Fairbanks Region 2005 - 2006 Surveys Irina V. Lapina, Susan C. Klein, and Matthew L. Carlson Alaska Natural Heritage Program Environment and Natural Resources Institute University of Alaska Anchorage 707 A Street Anchorage, Alaska 99501 Report funded and prepared for: US FOREST SERVICE State and Private Forestry June 2007 Table of Contents Non-Native Plant Species of the Fairbanks Region............................................................ 1 2005 - 2006 Surveys ........................................................................................................... 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 1 Methods............................................................................................................................... 1 Results................................................................................................................................. 3 Species diversity and distribution ................................................................................... 3 Noteworthy species......................................................................................................... 6 Noteworthy areas .......................................................................................................... 12 Recommendations............................................................................................................. 16 References........................................................................................................................ -

Crary-Henderson Collection, B1962.001

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Mary Langdon, Volunteer, and Sara Piasecki, Archivist TITLE: Crary-Henderson Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1962.001, B1962.001A OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1885-1930 Extent: 19.25 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): Will Crary; Nan Henderson; Phinney S. Hunt; Miles Bros.; Lyman; George C. Cantwell; Johnson; L. G. Robertson; Lillie N. Gordon; John E. Worden; W. A. Henderson; H. Schultz; Merl LaVoy; Guy F. Cameron; Eric A. Hegg Administrative/Biographical History: The Crary and Henderson Families lived and worked in the Valdez area during the boom times of the early 1900s. William Halbrook Crary was a prospector and newspaper man born in the 1870s (may be 1873 or 1876). William and his brother Carl N. Crary came to Valdez in 1898. Will was a member of the prospecting party of the Arctic Mining Company; Carl was the captain of the association. The Company staked the “California Placer Claim” on Slate Creek and worked outside of Valdez on the claim. Slate Creek is a tributary of the Chitina River, in the Chistochina District of the Copper River Basin. Will Crary was the first townsite trustee for Valdez. Carl later worked in the pharmaceutical field in Valdez and was also the postmaster. Will married schoolteacher Nan Fitch in Valdez in 1906. Carl died of cancer in 1927 in Portland, Oregon. -

Alaska Association for Historic Preservation - Nike Site Summit Tourism Development Project

Total Project Snapshot Report 2012 Legislature TPS Report 58433v1 Agency: Commerce, Community and Economic Development Grants to Named Recipients (AS 37.05.316) Grant Recipient: Alaska Association for Historic Federal Tax ID: 920085097 Preservation Project Title: Project Type: Remodel, Reconstruction and Upgrades Alaska Association for Historic Preservation - Nike Site Summit Tourism Development Project State Funding Requested: $50,000 House District: Anchorage Areawide (16-32) Future Funding May Be Requested Brief Project Description: Stabilize Buildings at Nike Site Summit Historic District in preparation for public tours. Funding Plan: Total Project Cost: $215,000 Funding Already Secured: ($5,000) FY2013 State Funding Request: ($50,000) Project Deficit: $160,000 Funding Details: FONSS is actively fundraising and seeking in-kind donations to continue the work to stabilize the Launch Control Building and Guided Missile Maintenance Facility. Total project cost as estimated by the Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER) is approximately $524,000. Our estimate of $407,670 is based on different assumptions for treating the buildings. Detailed Project Description and Justification: In preparation for guided tours of the Nike Site Summit Historic District scheduled to begin in the fall of 2012, FONSS began building stabilization of the Launch Control Building and the Guided Missile Maintenance Building in the summer of 2011. This followed successful completion of restoration of 3 Sentry Buildings and preliminary roof repairs at two Launch buildings during the summer of 2010 by volunteers. Donations from vendors, in-kind equipment loans and FONSS members have so far paid for repairs, but additional funds are needed to cover the "big jobs" that remain, as follows: Launch Control Building - The objective of stabilization is to seal the building from the elements, restore the exterior of the building to its historic Cold War appearance, and abate hazardous materials from inside the building to make it safe for visitors. -

MANAGING ALASKA LS NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS Janet Clemens Darrell Lewis

MANAGING ALASKA ’S NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS Janet Clemens National Park Service, 240 W. Fifth Ave., Anchorage, Alaska 99501; [email protected] Darrell Lewis National Park Service, Anchorage ABSTRACT The National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office, provides historic preservation technical assistance to National Historic Landmark (NHL) stewards. Preserving Alaska’s 49 landmarks offers many chal- lenges as well as opportunities for success through effective working relationships. A closer look at these management challenges and successes are detailed in the NHL case studies of Ladd Field and the Sitka Naval Operating Base and U.S. Army Coastal Defenses. keywords: cultural resources management, historic preservation assistance, federal partnerships INTRODUCTION Alaska’s national historic landmarks (NHLs) represent some of America’s most significant places. The stories as- sociated with these NHLs include information about an- cient hunting camps and villages, Russian exploration and settlements, Alaska Native education and civil rights or- ganizations, fur seal harvesting, mining and fish canning industries, and the World War II Aleutian battlegrounds. The 2005 designation of Amalik Bay Archeological District NHL (Fig. 1) within Katmai National Park and Preserve brings the total number of NHLs in Alaska to 49 (a list of Alaska NHLs is at http://www.nps.gov/akso/CR/ AKRCultural/NHL.htm). However, the landmark designation does not en- sure preservation of these cultural treasures. Preserving Figure 1. View of Amalik Bay Archeological District, Alaska’s NHLs is often a challenging process, and success Alaska’s most recently designated NHL. Photo courtesy of is largely dependent on responsible stewards and good Jeanne Schaaf, Katmai National Park and Preserve. -

Recent Publications on the History of Mining

Recent Publications on the History of Mining Compiled by Lysa Wegman-French The following bibliography contains books, Includes Arizona copper mines, the Colorado dissertations and theses, articles and chapters of Coal Wars, and communist miners involved in books, and other media—organized within those the Cold War civil rights struggle.] four categories—that provide new content relat- ed to the history of all types of mining in North Allan, Chris. Arctic Odyssey: A History of America (that is, Canada, the United States, and the Koyukuk River Gold Stampede in Alaska’s Far Central America). It does not include book re- North. Fairbanks: National Park Service, Fair- view articles, nor reissued or subsequent editions banks Administrative Center, 2016. of material. Digital capabilities are changing our options for Ammons, Doug. A Darkness Lit by Heroes: seeing works of interest. Some films and printed The [Butte] Granite Mountain-Speculator Mine works are available for viewing on the internet. Disaster of 1917. Missoula: Water Nymph Press, We have not included URLs for these, but check 2017. the internet for their availability. Moreover, some articles are available only on the internet; for these Andrist, Ralph K. The Gold Rush. [Scotts we have included the URL. In addition, many old- Valley, CA]: CreateSpace Independent Publish- er books are now being reissued as e-books, and ing, 2016. [Also an e-book.] older films are being distributed as DVDs. We did not include them in this compilation since the Anschutz, Philip F. Out Where the West Be- content is not new. However, if you are interested gins: Profiles, Visions, and Strategies of Early West- in an older work, check to see if it is now available ern Business Leaders. -

Institutions, Attitudes and LGBT: Evidence from the Gold Rush

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11957 Institutions, Attitudes and LGBT: Evidence from the Gold Rush Abel Brodeur Joanne Haddad NOVEMBER 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11957 Institutions, Attitudes and LGBT: Evidence from the Gold Rush Abel Brodeur University of Ottawa and IZA Joanne Haddad University of Ottawa NOVEMBER 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11957 NOVEMBER 2018 ABSTRACT Institutions, Attitudes and LGBT: Evidence from the Gold Rush* This paper analyzes the determinants behind the spatial distribution of the LGBT population in the U.S. -

Year 5 ARSLS Annual Report

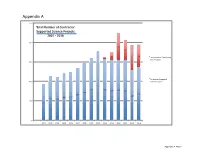

Appendix A 250 Total Number of Contractor Supported Science Projects 2001 - 2016 200 70 52 20 58 Environmental Compliance 4 65 Only Projects 150 Contractor Supported 100 Science Projects 177 159 158 154 155 155 146 134 136 128 120 123 113 111 50 92 0 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Appendix B Geographic Distribution of Contractor Supported Projects 2002 - 2016 Appendix C: Projects & Locations, 2016 and 2017 Projects throughout the Arctic – 2016/17/18 Field Projects in the Arctic Regions Supported by the ARSLS Contractor APP Year 5 2/1/2016 – 1/31/2017 Field Projects in the Arctic Regions Supported by the ARSLS Contractor APP year 6 2/1/2017 – 1/31/2018 Armap.org Appendix C1 2016 CONTRACTOR SUPPORTED SCIENCE PROJECTS Region Field Location(s) PI Award Program Comment Instrument sites near Firn compaction studies NNX15AC62 Greenland Raven, Summit, Abdalati NASA twin otter airport fees and flight time, 8 drums fuel, G Crawford Pt. truck rental, KISS user days 1 month project support - subcontract; 158 Cherskii Russia Cherskii Alexander 1304040 NSF\GEO\OPP\ARC\ARCSS user days Cape Espenberg 7k lbs freight, 100 gals gasoline, 240 lbs propane, Alaska Cape Espenberg Alix 1523160 NSF\GEO\OPP\ARC\ASSP camping gear, water system, field food, travel, camp manager and assistant, Various rivers Baffin Rivers reproposal Canada Alkire 1303766 NSF\GEO\OPP\ARC\ANS Island, Canada 729 lbs freight Alaska LeConte Glacier Amundson 1504288 NSF\GEO\OPP\ARC\ANS Helo and boat charters, camping gear Ny Alesund Norway (Svalbard), Arctic Arnosti 1332881 NSF\GEO\OCE Ny Alesund user days (44) Ocean Hulahula River, Alaska Arctic LCC ArcLCC FWS Toolik helicopter support to Hulahula River Toolik Small lake dynamics - fixed wing air support, 1k lbs freight,camping gear, Barrow, Teshekpuk, Alaska Arp 1417300 NSF\GEO\OPP\ARC\ARCSS snowmachine maintenance, NSB and UIC permits, Inigok, Toolik radios, toolik user days, barrow lodging and truck rental, Prudhoe user days. -

Albert G. Kingsbury Lantern Slide Collection, Circa 1880-1930

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81g0pj3 No online items A guide to the Albert G. Kingsbury lantern slide collection, circa 1880-1930 Processed by: L. Bianchi, July-August 2014. San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park Building E, Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94123 Phone: 415-561-7030 Fax: 415-556-3540 [email protected] URL: http://www.nps.gov/safr 2014 A guide to the Albert G. P97-025 (SAFR 23857) 1 Kingsbury lantern slide collection, circa 1880-1930 A Guide to the Albert G. Kingsbury lantern slide collection P97-025 San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, National Park Service 2014, National Park Service Title: Albert G. Kingsbury lantern slide collection Date: circa 1880-1930 Date (bulk): 1897-1915 Identifier/Call Number: P97-025 (SAFR 23857) Creator: Kingsbury, Albert G. Hegg, Eric A. Physical Description: 385 items. Repository: San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, Historic Documents Department Building E, Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94123 Abstract: The Albert G. Kingsbury lantern slide collection, circa 1880-1930, bulk 1897-1915, (SAFR 23857, P97-025) is comprised mainly of photographs of Alaska and the Yukon Territory of Canada during the Klondike Gold Rush and Nome Gold Rush as well as photographs of Mexico. The collection has been processed to the File Unit level, with some Items listed, and is open for use. Physical Location: San Francisco Maritime NHP, Historic Documents Department Language(s): In English. Access This collection is open for use unless otherwise noted. Glass lantern slides may require special handling by the reference staff. Publication and Use Rights Some material may be copyrighted or restricted. -

Richardson Highway / Steese Expressway Corridor Study Draft Purpose and Need

Richardson Highway / Steese Expressway Corridor Study Draft Purpose and Need The Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (ADOT&PF), in cooperation with the Alaska Division Office of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), is developing a Planning and Environmental Linkage (PEL) Study for the Fairbanks, Alaska area Richardson Highway / Steese Expressway corridors from Badger Road interchange (Richardson Highway milepost 360) to Chena Hot Springs Road interchange (Steese Highway milepost 5). Purpose The purpose of the study is to collaborate with State, local, and federal agencies, the general public, and interested stakeholders to develop a shared corridor concept that meets long ‐range transportation needs to improve safety, mobility, air quality, and freight operations. Additionally, the concept will promote improvements that reduce transportation deficiencies (e.g. delay and congestion), enhance the corridor’s sustainability (e.g. infrastructure longevity and maintenance costs), and minimize environmental and social impacts. Project Need Summary I – Safety Safety for motorized and non‐motorized traffic needs improvement by developing a corridor concept that: Upgrades the transportation infrastructure to current ADOT&PF design standards where practical Reduces conflict points Reduces the frequency and severity of crashes at “high crash locations” Improves pedestrian and bicycle crossings II – Mobility The mobility of people and goods in the corridor needs improvement by developing a concept that: Reduces delay -

150 Years of Change

1867-2017 150 years of change Áak'w Aaní at time of the Alaska Purchase March, 2017 Richard Carstensen Discovery Southeast funding from Friends of the Juneau- Douglas City Museum Place names Contents Preface: Late in 2016, returning to Juneau from nearly a year out of town with convention family affairs, I was offered a fascinating assignment. Looking ahead to the Seward's Day .................................................... 2 In all my writing since publi- Place names convention ................................. 2 sesquicentennial year of the 1867 Alaska Purchase, Jane Lindsey of Juneau- cation of Haa L’éelk’w Hás Historical context ............................................... 4 Douglas City Museum, and her friend Michael Blackwell imagined a before- Aani Saax’ú: Our grand- Methods ........................................................... 11 &-after 'banner' with an oblique view of Juneau from the air today. Alongside parents’ names on the land Three scenes..................................................... 15 (Thornton & Martin, eds. 1) Dzantik'i Héeni ........................................... 15 would be a retrospective, showing what the same view looked like at the time of purchase, 150 years ago. 2012), I’ve used Tlingit place 2) Áak'w Táak .................................................. 23 names whenever available, 3) Aanchgaltsóow .......................................... 31 In part, Jane and Mike's idea came from a split-image view of downtown followed by their translation Appendices ....................................................... 39 Juneau that I created 8 years ago, showing a 2002 aerial oblique on the right, in italic, and IWGN (impor- Appendix 1 CBJ Natural History Project ..... 39 and on the left, my best guess as to what Dzantik'i Héeni delta looked like in tant white guy name) in Appendix 2 LiDAR ......................................... 40 1879. I, in turn, had borrowed that idea from the Mannahatta project (Sander- parentheses. -

Sam's Resume-11-27-16.Pages

Sam Combs, AIA, NCARB, Architect Resume: Education: Americans With Disabilities Act Seminar, Evan Terry & Associates, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, 1992. Real Estate Course, Central Seattle Community College, 1990. Post-Graduate studies in Arctic Engineering, University of Alaska, 1977. Bachelor of Architecture, University of Oregon, 1977. High School Diploma, Dimond High School, Anchorage, Alaska, 1971 . Architectural Registration: State of Washington Architectural Registration, 1988. No. 4951. State of Hawaii Architectural Registration, 1986. No. AR-6075. [Past=P] State of Oregon Architectural Registration, 1986. No. 2763. [P] State of Alaska Architectural Registration, 1983. No. A-5628. Professional Affiliations: American Institute of Architects. National Trust for Historic Preservation. National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB). Washington Trust for Historic Preservation. [P] Historic Seattle. [P] Union Station Historic District Association. [P] Association for Preservation Technology. [P] The Society of Architectural Historians. [P] Alaska Association for Historic Preservation. [P] Historic Anchorage Inc. [P] Anchorage Historic Properties, Inc. [P] Forum '49. [P] Alaska World Affairs Council. Rotary International. [P] National Federation of Independent Business. [P] Pioneers of Alaska, Igloo Number 15. [P] Appointments and Awards: Appointed by Mayor Mark Begich to the re-formed Anchorage Historic Preservation Commission, 2007-2010. Past-President of the Alaska World Affairs Council, 2007-2008. President of the Alaska World Affairs Council, 2006-2007. Vice President of the Alaska World Affairs Council, 2005-2006. Executive Board of the Alaska World Affairs Council, 1992-2010. Elected to the Executive Board of the Alaska Association for Historic Preservation, 2002-2010; Appointed by Mayor Mystrom to the Housing & Neighborhood Development Commission (HAND) of the Municipality of Anchorage, 1999-02. -

Alaska Roads Historic Overview

Alaska Roads Historic Overview Applied Historic Context of Alaska’s Roads Prepared for Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities February 2014 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Alaska Roads Historic Overview Applied Historic Context of Alaska’s Roads Prepared for Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities Prepared by www.meadhunt.com and February 2014 Cover image: Valdez-Fairbanks Wagon Road near Valdez. Source: Clifton-Sayan-Wheeler Collection; Anchorage Museum, B76.168.3 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Table of Contents Table of Contents Page Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Project background ............................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Purpose and limitations of the study ................................................................................... 3 1.3 Research methodology ....................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Historic overview ................................................................................................................. 6 2. The National Stage ........................................................................................................................