The Performance of Change Through the G.I. Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HM 71 Recognizing Veteran Suicide SPONSOR(S): Willhite, Smith D

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STAFF ANALYSIS BILL #: HM 71 Recognizing Veteran Suicide SPONSOR(S): Willhite, Smith D. and others TIED BILLS: IDEN./SIM. BILLS: REFERENCE ACTION ANALYST STAFF DIRECTOR or BUDGET/POLICY CHIEF 1) Local Administration & Veterans Affairs 16 Y, 0 N Renner Miller Subcommittee 2) State Affairs Committee Renner Williamson SUMMARY ANALYSIS Since 2008, the number of veteran suicides has exceeded 6,300 each year. Many risk factors may affect veteran suicide rates including economic disparities, homelessness, and health issues such as traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse disorder. In 2007, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) developed a comprehensive program designed to reduce the incidence of suicide among veterans and launched the Veterans Crisis Line, a program that connects veterans and current servicemembers in crisis and their families and friends with information from qualified responders through a confidential toll-free hotline, online chat, and text messaging service. The VA partners with hundreds of organizations, both at the local and national level to raise awareness of the VA’s suicide prevention resources and to educate people about how they can support veterans and servicemembers in their communities. The VA also partners with community mental health providers to expand the network of local treatment resources available to veterans. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States. Although the VA emphasizes mental health care for veterans, many veterans do not reach out to the VA for help. Most use local hospitals and health clinics. However, community health providers are not prepared to address the needs of veterans. -

Veteran/Military Service Award Emblem Application

Veteran/ Military Service Award Emblem Application Military members or veterans can apply for an emblem packet. Each packet contains a U.S. veteran emblem and either a campaign ribbon and American flag or 2 campaign ribbons. Packets are $18 each. Requirements • You must provide proof that you are eligible to receive the emblems: • Former service members: Provide a copy of your DD 214 or other official military orders. • Active duty members: Provide a letter from a military office on their letterhead indicating what type of campaign medals were awarded. • You must be the legal or registered owner of the vehicle displaying the emblem. Take this application and supporting documentation to any vehicle licensing office (additional service fees may apply) or mail this application, required documents, and a check or money order for $18 per packet (payable to the Department of Licensing) to: Application and Issuance, Department of Licensing, PO Box 9048, Olympia, WA 98507. Display instructions • When the veteran emblem or military service aware emblem is displayed on a license plate, it must be displayed between the bottom license plate bolt holes. • U.S. flags and ribbon emblems must be displayed on the outside of each bottom license plate bolt hole. No more than two flags or small emblems may be affixed to any one license plate. If you have questions, email [email protected] or call (360) 902-3770. Applicant Veteran name (Area code) Phone number Mailing address (Street address or PO Box, City, State, ZIP code) Current Washington plate number Vehicle identification number (VIN) Model year Make Veterans remembrance/Military service emblem packets Enter number of emblems requested Air Force Cross Medal Emblem Navy Cross Medal Emblem Bronze Star Medal Emblem Silver Star Medal Emblem Distinguished Flying Cross Medal Emblem U.S. -

Union Army Pensions and Civil War Records

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Evolution of Retirement: An American Economic History, 1880-1990 Volume Author/Editor: Dora L. Costa Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-11608-5 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/cost98-1 Publication Date: January 1998 Chapter Title: Appendix A: Union Army Pensions and Civil War Records Chapter Author: Dora L. Costa Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c6116 Chapter pages in book: (p. 197 - 212) Appendix A: Union Army Pensions and Civil War Records Real data is messy. Tom Stoppard, Arcadia The scope of the Union anny pension program, run for the benefit of veterans and their dependent children and widows, came to be enormous. What had begun as a program to provide for severely wounded veterans became the first general disability and old-age pension program in the United States. The pro- gram was generous both in the level of benefits and in its coverage. The average pension paid to Union anny veterans from 1866 to 1912 replaced about 30 percent of the income of an unskilled laborer, making the Union army pension program as generous as Social Security retirement benefits today. The total number of beneficiaries collecting a pension was slightly more than 100,000 in 1866 but reached a peak of almost 1 million in 1902. By 1900 21 percent of all white males age fifty-five or older were on the pension rolls, and the program that had consumed a mere 3 percent of all federal government expen- ditures in 1866 consumed almost 30 percent. -

From War Zones to Jail: Veteran Reintegration Problems

From War Zones to Jail: Veteran Reintegration Problems William B. Brown Volume 8 – No. 1 – Spring 2011 1 Abstract When individuals return home from war they are not the same individuals who left for war. The Iraq and Afghanistan wars have been on-going since October 2001, and nearly two million service members have been deployed to these wars – many have been deployed multiple times. When military personnel return from war, and are discharged from military service, they are issued the label of veteran. Initially, this term has little meaning or significance to individuals recently released from military service. As they begin their process of reintegrating back into the civilian culture the term veteran begins to develop meaning for many veterans. That meaning is influenced by factors such as interpersonal relationships, education, and employment/unemployment experiences. Depending upon the level of influence that the Military Total Institution has had on the veteran, which includes the veteran’s combat experiences, many veterans find themselves confronted with mental health issues, particularly posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is an artifact of her or his combat experiences. A significant number of veterans with PTSD symptoms have turned to alcohol as a form of self-medication. Many veterans with PTSD say that alcohol reduces nightmares and difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep (DIMS). In many instances the experiences of war, PTSD, alcohol, combined with lethargic civilian attitudes of the problems veterans confront provides the ingredients of a recipe designed to accelerate the probability of increased veteran incarceration. This article addresses the aforementioned issues by analyzing the data collected during a study of 162 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans during a 15-month period, and spanning across 16 states. -

Domestic Propaganda, Visual Culture, and Images of Death on the World War II Home Front

Spectral Soldiers: Domestic Propaganda, Visual Culture, and Images of Death on the World War II Home Front James J. Kimble Rhetoric & Public Affairs, Volume 19, Number 4, Winter 2016, pp. 535-569 (Article) Published by Michigan State University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/650967 Access provided by Seton Hall University (19 Apr 2017 17:43 GMT) SPECTRAL SOLDIERS:DOMESTIC PROPAGANDA, VISUAL CULTURE, AND IMAGES OF DEATH ON THE WORLD WAR II HOME FRONT JAMES J. KIMBLE This essay argues against the prevailing historical conception that George Strock’s graphic photograph of three lifeless Marines—published by Life magazine on September 20, 1943—was the defınitive point when domestic U.S. propaganda began to portray increasingly grisly images of dead American soldiers. After considering how the visual culture of the home front made the photo’s publication a dubious prospect for the government, I examine a series of predecessor images that arguably helped construct a rhetorical space in which such graphic depictions could gradually gain public acceptance and that, ultimately, ushered in a trans- formation of the home front’s visual culture. [The] audience must be prepared for a work of art. —Kenneth Burke1 y 1945, grisly depictions of dead GIs were a common sight on the U.S. home front. Many civilians in that last year of World War II Bdoubtless found themselves gazing uncomfortably at a gruesome War Advertising Council (WAC) pamphlet, its cover displaying the photo- JAMES J. KIMBLE is Associate Professor of Communication & the Arts at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. -

Iraq War Clinician's Guide

IRAQ WAR CLINICIAN GUIDE 2nd EDITION Written and Compiled by National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Contributing authors include (in alphabetical order): Eve B. Carlson, Ph.D., Erika Curran, L.C.S.W., Matthew J. Friedman, M.D., Ph.D., Fred Gusman, M.S.W., Jessica Hamblen, Ph.D., Rachel Kimerling, Ph.D., Gregory Leskin, Ph.D., Brett Litz, Ph.D., Barbara L. Niles, Ph.D., Susan M. Orsillo, Ph.D., Ilona Pivar, Ph.D., Annabel Prins, Ph.D., Robert Rosenheck, M.D., Josef I. Ruzek, Ph.D., Paula P. Schnurr, Ph.D., Steve Southwick, M.D., Jane Stafford, Ph.D., Amy Street, Ph.D., Pamela J. Swales, Ph.D., Casey T. Taft, Ph.D., Robyn D. Walser, Ph.D., Patricia J. Watson, Ph.D., Julia Whealin, Ph.D.; and Harold Kudler, M.D., from the Durham VA Medical Center. Editorial Assistant: Sherry E. Wilcox. Walter Reed Army Medical Center Contributing authors include (in alphabetical order): LTC John C. Bradley, MC, USA, LTC David M. Benedek, MC, USA, COL Ryo Sook Chun, MC, USA, COL Dermot M. Cotter, COL Stephen J. Cozza, MC, USA, Catherine M. DeBoer, MAJ Geoffrey G. Grammer, CAPT Thomas A. Grieger, MC, USN, Rosalie M. Kogan, L.C.S.W., COL (Ret) R. Gregory Lande, DO FACN, Barbara A. Marin, Ph.D., COL (Ret) Patricia E. Martinez, MAJ Erin C. McLaughlin, Corina M. Miller, L.C.S.W., COL Theodore S. Nam, MC, USA, COL (Ret) Marvin A. Oleshansky, M.D., MAJ Mark F. Owens, LTC (Ret) Harold J. Wain, Ph.D., COL Douglas A. -

Trauma Depression

PTSD STRESS ANXIETY TRAUMA DEPRESSION STRESS ANXIETY PTSD DEPRESSION TRAUMA PTSD STRESS ANXIETY TRAUMA DEPRESSION STRESSLIVING WITHANXIETY PTSD TRAUMATRAUMATIC DEPRESSION STRESS Established in 1920 and chartered by Congress in 1932, DAV is a nonprofit national veterans service organization recognized as a fraternal organization under IRS regulations. DAV accepts no federal funding and relies on membership dues and charitable donations to sustain its many programs. Foreword For as long as there have been wars, western civilizations have recorded the existence of common psychological reactions to traumatic events. DAV assisted veterans from World War I who suffered from what was then called “shell shock.” In World War II, we served veterans whose symptoms were generally termed “battle fatigue.” In the late 1970s, to better understand and find a basis to treat the “invisible wounds” plaguing so many Vietnam veterans—the collection of symptoms we now know as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—DAV sponsored the Forgotten Warrior Project. This DAV study was crucial to the eventual recognition and ultimate adoption of PTSD in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980. Growing clinical acceptance and recognition of PTSD stemming from the Forgotten Warrior Project also led DAV to open centers for Vietnam veterans and their families in 70 cities nationwide. Following DAV’s lead, the Department of Veterans Affairs began its Readjustment Counseling Service in 1979. This program, now composed of 300 Vet Centers nationwide, remains one of the premier resources for war veterans who suffer from PTSD and other service-connected mental health issues. Now we must confront the challenges of assisting a new generation of combat veterans. -

Texas and the Bonus Expeditionary Army

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 23 Issue 1 Article 7 3-1985 Texas and the Bonus Expeditionary Army Donald W. Whisenhunt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Whisenhunt, Donald W. (1985) "Texas and the Bonus Expeditionary Army," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 23 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol23/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 27 TEXAS AND THE BONUS EXPEDITIONARY ARMY by Donald W. Whisenhunt By 1932 the United States was in the midst of the most severe economic depression in its history. For several years, but especially since the Stock Market Crash of 1929, conditions had been getting worse by the month. By the summer of 1932 the situation was so bad that many plans to end the depression were put forward by various groups. Texas suffered from the Great Depression just as much as the rest of the country.' Rising uuemployment, a decline in foreign commerce, and the reduction of farm prices combined to make life a struggle during the 1930s. When plans, no matter how bizarre, were offered as solu tions, many Texans joined the movements. One of the most interesting and one that gathered much support was the veterans bonus issue. -

Business Fee Exemption for Veteran-Owned and Reservist-Owned Small Businesses Act 135 of 2016 (51 Pa.C.S

Business fee exemption for veteran-owned and reservist-owned small businesses Act 135 of 2016 (51 Pa.C.S. §§ 9610-9611) Veterans and reservists starting a small business in the Commonwealth are exempt from the payment of a business fee effective January 2, 2017. A business fee is any fee required to be paid to the Commonwealth or a political subdivision for starting or opening a business within Pennsylvania. The term does not include a fee for maintaining licensure or other requirement for continuing to operate a business. A small business must be independently owned, not dominant in its field of operation and employ 100 or fewer employees. A veteran- or reservist-owned small business must be owned and controlled by a veteran/veterans or reservist/reservists. A veteran is an individual who served in the United States Armed Forces, including a reserve component or the National Guard, and who was discharged or released from service under conditions other than dishonorable. A reservist is a member of a United States Armed Forces reserve component or National Guard. The filing fees for the following documents will be waived by the Bureau of Corporations and Charitable Organizations, when the documents are signed by the veteran or reservist and submitted with proof of the veteran's or reservist's status: • Articles of Incorporation (for profit) - $125 [DSCB:15-1306/2102/2303/2703/2903/3101/3303/7102] • Articles of Incorporation (nonprofit) [DSCB:15-5306/7102] - $125 • Certificate of Organization [DSCB:15-8821] - $125 • Certificate of Limited Partnership [DSCB:15-8621] - $125 • Registration - Domestic Registered Limited Liability Partnership [DSCB:15-8201A] - $125 • Foreign Registration Statement [DSCB:15-412] - $250 • Registration of Fictitious Name [DSCB:54-311] - $70 The above-listed business formation documents may be submitted directly from the veteran or reservist or submitted through a law firm or service company. -

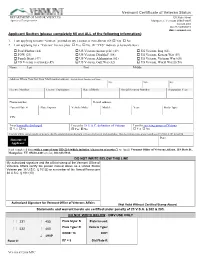

Vermont Certificate of Veteran Status

Vermont Certificate of Veteran Status DEPARTMENT OF MOTOR VEHICLES 120 State Street Agency of Transportation Montpelier, Vermont 05603-0001 802.828.2000 888-99-VERMONT dmv.vermont.gov Applicant Section (please completely fill out ALL of the following information): 1. I am applying to have “Veteran” printed on my License or Non-Driver ID: Yes No 2. I am applying for a “Veteran” license plate: Yes No (If “YES” indicate selection below) Pearl Harbor (44) US Veteran (motorcycle) (49) US Veteran, Iraq (63) POW (23) US Veteran, Disabled† (08) US Veteran, Korean War (59) Purple Heart (47) US Veteran, Afghanistan (61) US Veteran, Vietnam War (60) US Veteran (car/truck) (49) US Veteran, Gulf War (62) US Veteran, World War II (58) Name: Last First Middle Address Where You Get Your Mail (mailing address) - Include Street Number and Name City: State: Zip: License Number: License Expiration: Date of Birth: Social Security Number: Separation Year: Phone number: E-mail address: Current Plate #: Plate Expires: Vehicle Make: Model: Year: Body Type: VIN: I was honorably discharged I meet the 38 U.S.C. definition of Veteran I am the surviving spouse of Veteran Yes No Yes No Yes No I hereby affirm, under penalty of perjury, that the information on this form is true to the best of my knowledge. This declaration made under penalties of 23 VSA § 202 & § 4110. Date: Signature of Applicant: Send completed form with a copy of your DD-214 (which includes “character of service”) to: (mail) Vermont Office of Veterans Affairs, 118 State St., Montpelier, VT 05620-4401 or (fax) 802.828.5932. -

A Veteran's Perspective

A Veteran’s Perspective Authors: Mark DePue and Joy Lyman Grade Levels: 8-12 Purpose: To enhance student knowledge and understanding of contemporary American his- tory, especially our nation’s involvement in foreign wars and the impact the war had on a soldier, by listening to and/or reading a veteran’s personal interview. Objectives: Upon completing the activities presented in this Resource Guide, students will: Use an oral history interview, a Primary Source, to gather information, and interpret it in conjunction with secondary or other primary source accounts of the events, Enhance their knowledge and understanding of the United State’s involvement in recent wars, Expand and enhance research skills as he/she conducts background research to better un- derstand a veteran’s personal story, Broaden and refine writing skills and/or oral presentation skills, Demonstrate an appreciation for the service and sacrifices of America’s veterans. Materials: Internet access, headphones, audio equipment for listening to interview clips, and reference materials for further research. The Veteran’s Remember site can be found at: http://www2.illinois.gov/alplm/library/ collections/oralhistory/VeteransRemember/Pages/default.aspx 1 Illinois State Learning Standards: Middle/Junior High School: SS.16.A.3c: Identify the differences between historical fact and interpretation. ELA.5.B.3b: Identify, evaluate and cite primary sources. ELA.5.C.3a: Plan, compose, edit and revise documents that synthesize new meaning gleaned from multiple sources. Early High School: SS.16.A.4a: Analyze and report historical events to determine cause-and-effect relationships. ELA.5.B.4b: Use multiple sources and multiple formats; cite according to standard style manuals. -

Veterans Info

1 Information for Veterans, Military Service Members, Transitioning Service Members and Military Spouses Veterans, military service members, transitioning service members and military spouses of the armed forces of the United States, including the National Guard, may be eligible for exam point credits and/or expedited application processes. The information on this page is applicable to individuals who may qualify for these services. Before proceeding, determine if you meet the requirements in one or more of the following categories: A veteran who has been honorably discharged from active duty service in the armed forces of the United States Category 1 or on active duty in a reserve component of the armed forces of the United States, including the National Guard, during wartime or during any conflict when military personnel were committed by the President of the United States; Category 2 Active or reserve member of the United States Armed Forces (including the National Guard); Category 3 Transitioning service member of the military who is on active duty status, or on separation leave, who is within 24 months of retiring or 12 months of separation; Category 4 The spouse of persons who qualify in category 2 and/or category 3. The remainder of this information is relevant to individuals who fall under one or more of the categories noted above. If you do not fall under any of the aforementioned categories, DO NOT READ ANY FURTHER, as you will not qualify for any of the services reserved for veterans, military service members, transitioning service members and military spouses of the armed forces of the United States, including the National Guard.