Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery (PRS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renewal Journal Vol 4

Renewal Journal Volume 4 (16-20) Vision – Unity - Servant Leadership - Church Life Geoff Waugh (Editor) Renewal Journals Copyright © Geoff Waugh, 2012 Renewal Journal articles may be reproduced if the copyright is acknowledged as Renewal Journal (www.renewaljournal.com). Articles of everlasting value ISBN-13: 978-1466366442 ISBN-10: 1466366443 Free airmail postage worldwide at The Book Depository Renewal Journal Publications www.renewaljournal.com Brisbane, Qld, 4122 Australia Logo: lamp & scroll, basin & towel, in the light of the cross 2 Contents 16 Vision 7 Editorial: Vision for the 21st Century 9 1 Almolonga, the Miracle City, by Mell Winger 13 2 Cali Transformation, by George Otis Jr 25 3 Revival in Bogatá, by Guido Kuwas 29 4 Prison Revival in Argentina, by Ed Silvoso 41 5 Missions at the Margins, Bob Ekblad 45 5 Vision for Church Growth, by Daryl & Cecily Brenton 53 6 Vision for Ministry, by Geoff Waugh 65 Reviews 95 17 Unity 103 Editorial: All one in Christ Jesus 105 1 Snapshots of Glory, by George Otis Jr. 107 2 Lessons from Revivals, by Richard Riss 145 3 Spiritual Warfare, by Cecilia Estillore Oliver 155 4 Unity not Uniformity, by Geoff Waugh 163 Reviews 191 Renewal Journals 18 Servant Leadership 195 Editorial: Servant Leadership 197 1 The Kingdom Within, by Irene Alexander 201 2 Church Models: Integration or Assimilation? by Jeanie Mok 209 3 Women in Ministry, by Sue Fairley 217 4 Women and Religions, by Susan Hyatt 233 5 Disciple-Makers, by Mark Setch 249 6 Ministry Confronts Secularisation, by Sam Hey 281 Reviews 297 19 -

Guidelines for Handouts JM

1 UCL - INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL0017 GREEK ART AND ARCHITECTURE 2018-19 15 credits Year 2/3 BA Module Coordinator: Professor Jeremy Tanner Office: IoA 105; Office hours: Tuesday 11-12, Wednesday 11-12 or by appointment Email: [email protected]; phone: 7679 1525 2nd/3rd year module Turnitin Class ID: 3884021 Turnitin Password IoA1819 Coursework deadline: Hand in Essay in Class Tuesday 11th – handbacks provisionally on Friday 14th, afternoon Please see the last page of this document for important information about submission and marking procedures, or links to the relevant webpages 1. OVERVIEW OF MODULE: This module provides an introduction to Greek painting, sculpture and architecture in the period 800-50 BC. In the context of a broadly chronological survey, particular attention will be paid to the relationship between Greek art and society. Problems addressed will include: stylistic change and innovation, the role of the state in the development of Greek art, religious ideology and religious iconography, word and image, the social contexts and uses of art. Regular remodule will be made to the largest collection of Greek art outside Athens, the British Museum MODULE SCHEDULE Lectures will be held on Tuesdays 9-11am, IoA Room 209 Tutorials will be held on Thursdays in the British Museum – as scheduled – 12-3pm ARCL0017: GREEK ART AND ARCHITECTURE - MODULE SCHEDULE 2/10/18 1. and 2. Introduction to the Module and the the British Museum PART I: PRE-CLASSICAL? THE ORIENTAL ORIGINS OF WESTERN ART 9/10/18 3. From Geometric to Orientalising: the Dark Ages and Light from the East 4. -

NINETY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING at the Invitation of the UNIVERSITY of KENTUCKY Radisson Plaza Hotel Lexington Lexington, Kentucky, April 3-5, 2003

Classical Association of the Middle West and South Program of the NINETY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING at the invitation of THE UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY Radisson Plaza Hotel Lexington Lexington, Kentucky, April 3-5, 2003 Wednesday, April 2, 2003 5:00 - 8:00 p.m. Registration and Book Display Daniel Boone BOOK DISPLAY: An exhibit of books and other instructional materials will be in the Daniel Boone Room. It will be open on Thursday 8:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m.; Friday 8:00 a.m.-12:00 p.m.; and Saturday 8:00 a.m.-3:00 p.m. Coffee will be available. 6:00-10:00 p.m. Meeting of the Executive Committee Black Diamond 8:00-10:00 p.m. Cash Bar Reception Spirits Sponsored by Asbury College, Centre College, Georgetown College and Transylvania University Local Committee: Estelle Bayer (Madison Central High School) James Butler (Berea College) Bari Conder (Madison Central High School) James Francis (University of Kentucky) George Harrison (Xavier University) Kelly Kusch (Covington Latin School) Jason Lamoreaux (University of Kentucky) Hubert Martin (University of Kentucky) Jim Morrison (Centre College) Robert Rabel (University of Kentucky) Jane Phillips (University of Kentucky) Chair Randy Richardson (Asbury College) Cathy Scaife (Lexington Catholic High School) John Svarlien (Transylvania University) Diane Arnson Svarlien (Georgetown College) Terence Tunberg (University of Kentucky) 1 Classical Association of the Middle West and South Thursday April 3, 2003 8:00 - 5:00 Registration and Book Display Daniel Boone 8:00 - 10:30 am Meeting of the Executive Committee Black Diamond 8:15 - 9:45 am First Session Grand Ballroom II Section A Drama at Rome Thomas E. -

2010 Music Accessories Equipment

Product Catalog / Winter 2009 - 2010 Music Accessories Equipment ELUSIVE DISC To order Toll Free call: Fax: 765-608-5341 4020 Frontage Rd. Anderson, IN 46013 Info: 765-608-5340 SHOP ON-LINE AT: 1-800-782-3472 e-mail: [email protected] www.elusivedisc.com ContentsSACD SACD SACD 1-35 Accessories 74-80 04. Analogue Productions 75. Gingko Audio 10. Chesky 78. Mobile Fidelitiy 15. Fidelio Audio 78. Record Research Labs 15. Groove Note 79. Audioquest 21. Mercury Living Presence 80. Audience 21. Mobile Fidelity 80. VPI 24. Pentatone 80. Michael Fremer 25. Polydor 80. Shakti 27. RCA 28. Sony 31. Stockfisch Equipment 81-96 31. Telarc 35. Virgin 81. Amps / Tuners / Players 83. Cartridges 86. Headphones XRCD 36-39 89. Loudspeakers 90. Phono Stages 36. FIM 92. Record Cleaners 36. JVC 93. Tonearms 94. Turntables Vinyl 40-73 41. Analogue Productions 43. Cisco 43. Classic Records 48. EMI 52. Get Back 53. Groove Note Records 54. King Super Analogue 55. Mobile Fidelity 57. Pure Pleasure Records 59. Scorpio 59. Simply Vinyl 60. Sony 60. Speaker’s Corner 63. Stockfisch 63. Sundazed 66. Universal 68. Vinyl Lovers 69. Virgin 69. WEA 4020 Frontage Rd. Info: 765-608-5340 72. Warner Brothers / Rhino Anderson, IN 46013 Orders: 800-782-3472 www.elusivedisc.com SACD SACD The Band / Music From Big Pink Pink Floyd / The Dark Side Of The Moon Tracked in a time of envelope-pushing Arguably the greatest rock album ever studio experimentations and pop released now available for the first psychedelia, Music From Big Pink is a time in Super Audio CD! This marks watershed album in the history of rock. -

Fiches Pédagogiques Cycle 3

Fiches pédagogiques cycle 3 Activités proposées au Cycle 3 du PER lors de l'édition 2014 Disciplines Titre Années Descriptif d'enseignement Le réseau social ask.fm a la faveur des adolescents. N'importe qui peut poser des questions, souvent de manière anonyme, à ceux qui ont ouvert un compte. Si certains cas de persécution ont été amplement Ask.fm : l'interrogatoire FG MITIC, FG médiatisés, la plupart des usagers attendent un bénéfice en termes de 9-11 reconnaissance de soi et de valorisation. fantôme Santé, bien-être Tableau à remplir individuellement par les élèves Fiche pour aider à animer le débat en classe FG MITIC, FG Des jeunes femmes parées de leurs plus beaux atours flashy, é tendues Santé, bien-être, sur le sol feuillu d'un sous-bois grisâtre. Une publicité parue en 2013 Dior, j'adore ? Analyse Langue 1 9-11 dans le quotidien LE MONDE, inspirée du "Déjeuner sur l'herbe" de d'une publicité français, Arts Manet. Mais pour quelle représentation de la femme, du bien-être et visuels de la réussite ? Analyse d'une image fixe. L’homme n’a jamais marché sur la Lune ; les attentats du 11 Les "théories du septembre 2001 ont été mis en scène par le gouvernement américain : complot" : quelle valeur FG MITIC 10-11 quelle attitude avoir face aux sites et aux films qui démontent des leur accorder ? événements connus et en proposent une interprétation radicalement différente ? Comment mesurer son esprit critique ? De nombreuses informations ou rumeurs circulent sur Internet. Les FG MITIC, journalistes des méd ias traditionnels sont amenés à les recouper et les FACTUEL : la radio sur le Langue 1 vérifier pour en tirer un éventuel bénéfice. -

Alfred Kubin in the Night Museum Rediscovering a Lost Austrian Master of the Macabre at Neue Galerie New York

NOV/DEC 2008-JAN 2009 www.galleryandstudiomagazine.com VOL. 11 NO. 2 New York GALLERY&STUDIO The World of the Working Artist Alfred KUBIN KUBIN KUBIN KUBIN (1877-1959) Die Dame auf dem Pferd (The Lady on the Horse), ca. 1900-01 Pen and ink, wash, and spray on paper 39.7 x 31 cm (15 5/8 x 12 1/4 in.) Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, Kubin-Archiv Alfred Kubin in the Night Museum Rediscovering a lost Austrian master of the macabre at Neue Galerie New York by Ed McCormack, pg. 20 JESSICA FROMM Linear Visions “021” Oil on canvas 48” x 36” 48” Oil on canvas “021” November 25 - December 20, 2008 Catalog Available 530 West 25th St., NYC, 10001 Tues - Sat 11 - 6pm 212 367 7063 www.nohogallery.com GALLERY&STUDIO NOV/DEC 2008-JAN 2009 VINCENT ARCILESI Arcilesi in Mexico Paintings and Drawings Pyramid of the Sun, 2007 - 08, oil on canvas, 3panels, 9ft x 18ft November 18 - December 7, 2008 Broome Street Gallery 498 Broome Street, New York, N.Y. 10013 Tuesday - Sunday 11am - 6pm 212 226 6085 Some Editorial Afterthoughts on the Magnificent Turner Exhibition at the Met by Ed McCormack I can’t quote from it verbatim, because as soon as I read it the magazine flew from my hand as though of its own accord, landing at the opposite end of my writing room, and must have been been disposed of during one of this veritable garbage gar- den’s periodic prunings. But in a “Critic’s Notebook” column of the New Yorker, G&S Peter Schjeldahl wrote something to the effect that J.M.W. -

Baixar Este Arquivo

Reitor Ricardo Marcelo Fonseca Vice-Reitora Graciela Inês Bolzón de Muniz Pró-Reitor de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação Francisco de Assis Mendonça Pró-Reitor de Extensão e Cultura Leandro Franklin Gorsdorf História: Questões & Debates, ano 38, volume 69, n. 1, jan./jun. 2021 Publicação semestral do Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da UFPR e da Associação Paranaense de História (APAH) Editora Priscila Piazentini Vieira Conselho Editorial Marion Brepohl (Universidade Federal do Paraná, Presidente do Conselho), Álvaro Araújo Antunes (Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto), Ana Paula Vosne Martins (Universidade Federal do Paraná), Ana Silvia Volpi Scott (Universidade Estadual de Campinas), Angelo Priori (Universidade Estadual de Londrina), André Macedo Duarte (Universidade Federal do Paraná), Antonio Cesar de Almeida Santos (Universidade Federal do Paraná), Carlos de Almeida Prado Bacellar (Universidade Estadual de São Paulo), Carlos Jorge Gonçalves Soares Fabião (Universidade de Lisboa), Claudia Rosas Lauro (Pontificia Universidade Católica do Peru), Claudine Haroche (Universidade Sorbonne), Christian Laval (Universidade Paris Nanterre), Euclides Marchi (Universidade Federal do Paraná), José Guilherme Cantor Magnani (Universidade Estadual de São Paulo), José Manuel Damião Rodrigues (Universidade de Lisboa), Luiz Carlos Villalta (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais), Márcio Sergio Batista Silveira de Oliveira (Universidade Federal do Paraná), Luiz Geraldo Santos da Silva (Universidade Federal do Paraná), Marcos Napolitano (Universidade Estadual -

Interpreting the Seventh Century BC Explores the Range of Archaeological Information Now Available for the Seventh Century in Greek Lands

Interpreting the Seventh Century BC explores the range of archaeological information now available for the seventh century in Greek lands. It combines accounts of recent ( and Morgan Charalambidou discoveries (which often enable reinterpretation of older fnds), regional reviews, and archaeologically focused critique of historical and art historical approaches and Interpreting the interpretations. The aim is to make readily accessible the material record as currently understood and to consider how it may contribute to broader critiques and new directions in research. The geographical focus is the old Greek world encompassing Seventh Century BC Macedonia and Ionia, and extending across to Sicily and southern Italy, considering also the wider trade circuits linking regional markets. eds ) Tradition and Innovation XENIA CHARALAMBIDOU is research associate/postdoctoral researcher at the Fitch Edited by Laboratory of the British School at Athens and a member of the Swiss School of BC Century the Seventh Interpreting Archaeology in Greece. Her current research, which focuses on Euboea and Naxos in the Aegean, includes interdisciplinary projects which combine macroscopic study and Xenia Charalambidou and Catherine Morgan petrological analysis of ceramics in context. She has published widely in journals and conference proceedings. CATHERINE MORGAN is Senior Research Fellow in Classics at All Souls College, Oxford, and Professor of Classics and Archaeology at the University of Oxford. She was until 2015 Director of the British School at Athens. Her current work, which focuses on the Corinthia and the central Ionian Islands, includes a survey and publication project in northern Ithaca in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities of Kephallonia. Her publications include Isthmia VIII (1999) and Early Greek States Beyond the Polis (2003). -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/23/2021 07:28:57PM Via Free Access 24 Chapter One Polytheism

CHAPTER ONE MANY GODS COMPLICATIONS OF POLYTHEISM Gods, gods, there are so many there’s no place left for a foot. Basavanna 1. Order versus Chaos Worn out by hardship, having drifted ashore after two nights and two days in the seething waves of a stormy sea, Odysseus is hungry. In his distress he addresses the first—and only—girl that meets his eyes with, as Homer Od. 6.149–153 reports, the gentle and cunning words: “Are you a goddess or a mortal woman? If a goddess, it is of Artemis that your form, stature, and figure εἶδός( τε μέγεθός τε φυήν) most remind me.” Not an unseasonable exordium under the circumstances. When, some 1300 years after this event, the inhabitants of the city of Lystra in the region of Lycaonia (Asia Minor) witnessed the apostles Paul and Barnabas preaching and working miracles, they took them to be gods in the likeness of men.1 Hungry too, or so they thought. So the priest of ‘Zeus who is before the city’ supplied oxen in order to bring a sacrifice in honour of their divine visitors,2 christening Barnabas Zeus and Paul Hermes because the latter “was the principal speaker,” as we read in the Acts of the Apostles. Hungry gods and deified mortals, as well as the interaction between rhetorical praise and religious language belong to the most captivat- ing phenomena of Greek religion. They will all return in later chap- ters of this book. The present chapter will be concerned with another theme prompted by these two charming anecdotes, namely that of 1 Acts 14.11: “The gods, having taken on human shape, have come down to us.” 2 Acts 14.13 mentions only θύειν, while 14.19 has θύειν αὐτοῖς (to sacrifice to them). -

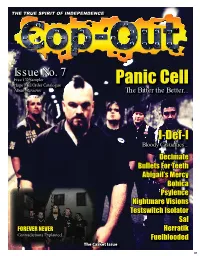

Cop out Magazine 07 – Web Version

TTHEHE TRUETRUE SPIRITSPIRIT OFOF INDEPENDENCEINDEPENDENCE IIssuessue No.No. 7 FFreeree CCDD SSamplerampler PPanicanic CCellell HHugeuge MMailail OOrderrder CCatalogueatalogue AAlbumlbum RReviewseviews TThehe BBitteritter tthehe BBetter...etter... II-Def-I-Def-I BBloodyloody CCasualties...asualties... DDecimateecimate BBulletsullets ForFor TeethTeeth AAbigail’sbigail’s MMercyercy BBohicaohica PPsylencesylence NNightmareightmare VVisionsisions TTestswitchestswitch IIsolatorsolator SSalal FFOREVEROREVER NNEVEREVER HHerratikerratik CContradictionsontradictions EExplained...xplained... FFuelbloodeduelblooded TThehe CCasketasket IssueIssue 01 02 CCOP-OUTOP-OUT #7#7 IIss bboughtought ttoo yyouou withwith thhee hhelpelp aandnd aassistences of the following people. Welcome To Cop-Out 07 sistence of the following people. HHelloello andand welcomewelcome toto anotheranother instalmentinstalment ofof Cop-Out,Cop-Out, thethe underfunded,underfunded, badlybadly writtenwritten andand cclobberedlobbered togethertogether catazinecatazine fromfrom thosethose jokersjokers atat CoproCopro Towers.Towers. SomeSome ofof youyou willwill bebe sur-sur- EEDITORDITOR JJoseose GGrifriffi n pprisedrised toto fi nnallyally havehave anotheranother oneone ofof thesethese fallfall onon youryour doordoor mat,mat, somesome ofof you,you, willwill bebe wonder-wonder- [email protected]@coproreords.co.uk iingng jjustust wwhathat tthehe hellhell thisthis is,is, butbut hopefullyhopefully allall ofof you,you, oror atat thethe veryvery leastleast mostmost ofof you,you, -

Athenian History and Democracy in the Monumental Arts During the Fifth Century BC

Athenian History and Democracy in the Monumental Arts during the Fifth Century BC Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lincoln Thomas Nemetz-Carlson, M.A. History Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Greg Anderson, Advisor Dr. Tim Gregory Dr. Mark Fullerton Copyright by Lincoln Thomas Nemetz-Carlson 2012 Abstract ! This study examines the first representations of historical events on public monuments in Athens during the fifth century BC. In the Near East and Egypt, for much of their history, leaders commonly erected monuments representing historical figures and contemporary events. In Archaic Greece, however, monuments rarely depicted individuals or historical subjects but, instead, mostly displayed mythological or generic scenes. With the reforms of Cleisthenes in 508/7 BC, the Athenians adopted a democratic constitution and, over the next century, built three different monuments which publicly displayed historical deeds. This dissertation looks to explain the origins of these three “historical monuments” by exploring the relationship between democracy and these pieces of art. The first chapter looks at monumental practices in the Archaic Era and explains why, unlike in the Near East and Egypt, the Greeks did not usually represent contemporary figures or historical events on monuments. This chapter suggests that the lack of these sort of honors is best explained by the unique nature of the Greek polis which values the well-being of the community over the individual. The second chapter concerns the origins of the first sculpture group of Tyrant Slayers, who were granted unprecedented commemorative portraits in the Agora most likely in the last decade of the sixth century. -

FAS 09 December 92Electronic

FAS Newsletter Federation of Astronomical Societies http://www.fedastro.org.uk Another Successful FAS Convention he 2009 FAS Annual Convention was Jerry’s talk was entitled Apollo Revisited T once again held at The Institute of As- and he took us through the Apollo project tronomy, Cambridge. In spite of not being from the early Saturn rocket launches to the the most convenient location for many people Moon Walks to the final days of the project. it does seem to be the preferred venue for He felt this was a timely subject as we were such events. celebrating 400 years since the invention of After refreshments, kindly organised by the telescope and 40 years since the first land- members of Cambridge AS, the event got ing on the Moon. underway with a talk by Dr Haley Gomez of It was refreshing to hear a talk illustrated Cardiff University. Her talk, Herschel - Un- with slides, instead of the more common veiling the cool universe, described the PowerPoint presentations. The phrase ’next Herschel infra-red telescope and its objectives. slide please’ is rarely heard these days. Jerry With its 3.5metre diameter mirror it will also told the gathering about his recent trip to collect long-wavelength radiation from the China to view the eclipse. coldest and most distant parts of the Uni- The AGM of the FAS was held next and verse. In particular, using infra-red this will be Richard Sargent led the meeting with aplomb. able to ’see’ through the dust clouds which In addition to normal AGM business a signifi- frustrate most other forms of telescope.