Klezmer: an Exploration of a Genre Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rokdim-Nirkoda” #99 Is Before You in the Customary Printed Format

Dear Readers, “Rokdim-Nirkoda” #99 is before you in the customary printed format. We are making great strides in our efforts to transition to digital media while simultaneously working to obtain the funding מגזין לריקודי עם ומחול .to continue publishing printed issues With all due respect to the internet age – there is still a cultural and historical value to publishing a printed edition and having the presence of a printed publication in libraries and on your shelves. עמותת ארגון המדריכים Yaron Meishar We are grateful to those individuals who have donated funds to enable והיוצרים לריקודי עם financial the encourage We editions. printed recent of publication the support of our readers to help ensure the printing of future issues. This summer there will be two major dance festivals taking place Magazine No. 99 | July 2018 | 30 NIS in Israel: the Karmiel Festival and the Ashdod Festival. For both, we wish and hope for their great success, cooperation and mutual YOAV ASHRIEL: Rebellious, Innovative, enrichment. Breaks New Ground Thank you Avi Levy and the Ashdod Festival for your cooperation 44 David Ben-Asher and your use of “Rokdim-Nirkoda” as a platform to reach you – the Translation: readers. Thank you very much! Ruth Schoenberg and Shani Karni Aduculesi Ruth Goodman Israeli folk dances are danced all over the world; it is important for us to know and read about what is happening in this field in every The Light Within DanCE place and country and we are inviting you, the readers and instructors, 39 The “Hora Or” Group to submit articles about the background, past and present, of Israeli folk Eti Arieli dance as it is reflected in the city and country in which you are active. -

A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of the Rose Tattoo

RSA JOU R N A L 25/2014 GIULIANA MUS C IO A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of The Rose Tattoo A transcultural perspective on the film The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955), written by Tennessee Williams, is motivated by its setting in an Italian-American community (specifically Sicilian) in Louisiana, and by its cast, which includes relevant Italian participation. A re-examination of its production and textuality illuminates not only Williams’ work but also the cultural interactions between Italy and the U.S. On the background, the popularity and critical appreciation of neorealist cinema.1 The production of the film The Rose Tattoo has a complicated history, which is worth recalling, in order to capture its peculiar transcultural implications in Williams’ own work, moving from some biographical elements. In the late 1940s Tennessee Williams was often traveling in Italy, and visited Sicily, invited by Luchino Visconti (who had directed The Glass Managerie in Rome, in 1946) for the shooting of La terra trema (1948), where he went with his partner Frank Merlo, an occasional actor of Sicilian origins (Williams, Notebooks 472). Thus his Italian experiences involved both his professional life, putting him in touch with the lively world of Italian postwar theater and film, and his affections, with new encounters and new friends. In the early 1950s Williams wrote The Rose Tattoo as a play for Anna Magnani, protagonist of the neorealist masterpiece Rome Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945). However, the Italian actress was not yet comfortable with acting in English and therefore the American stage version (1951) starred Maureen Stapleton instead and Method actor Eli Wallach. -

Contemporary Jewish Music and Culture Spring 2013 Judaic Studies Special Topics 563:225:01 Tuesday and Thursdays 6:10-7:30Pm Dr

Contemporary Jewish Music and Culture Spring 2013 Judaic Studies Special Topics 563:225:01 Tuesday and Thursdays 6:10-7:30pm Dr. Mark Kligman ([email protected]) Office Hours Tuesday 5:00-6:00, Room 203 12 College Ave, Rm 107 Course Description This course will look at Contemporary Jewish Music. “Contemporary” for this class is defined as music created from the 1950s to the present. The thrust of this investigation will be Jewish music in America and Israel since the 1970s. In order to contextualize Jewish music in America the music prior to this period, the music of Jews with roots in Europe, will begin our discussion. Issues such as Jewish identity, authenticity, religion and culture will be ongoing in our discussion. One overarching topic is the ongoing nature of tradition and innovation. An ethnographic approach will inform the issues to see your culture plays a role in shaping, informing and intrinsically a part of music in Jewish life. Contemporary music in Israel will also be examined and will highlight some similarities to music in America as well as illustrate key differences. The course will be divided into three almost equal sections: contemporary Jewish music in America in Religious contexts (Orthodox, Conservative and Reform); klezmer music; and, Israeli music. The readings assigned for each course will provide a good deal of historical and contextual information as related to musicians and musical genres. At each class sessionsmusical examples (both audio and video) will demonstrate key musical selections. Historical, informational and cultural background of Jewish life will be part of the readings for each session. -

Delmer Daves ̘͙” ˪…˶€ (Ìž'í'ˆìœ¼ë¡Œ)

Delmer Daves ì˜í ™” 명부 (작품으로) The Hanging https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-hanging-tree-1193688/actors Tree Demetrius and https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/demetrius-and-the-gladiators-1213081/actors the Gladiators Dark Passage https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dark-passage-1302406/actors Never Let Me https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/never-let-me-go-1347666/actors Go The https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-badlanders-1510303/actors Badlanders Cowboy https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/cowboy-1747719/actors Kings Go https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kings-go-forth-2060830/actors Forth Drum Beat https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/drum-beat-2081544/actors Jubal https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/jubal-2481256/actors Hollywood https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hollywood-canteen-261550/actors Canteen Rome https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rome-adventure-319170/actors Adventure Bird of https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bird-of-paradise-3204466/actors Paradise The Battle of https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-battle-of-the-villa-fiorita-3206509/actors the Villa Fiorita The Red https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-red-house-3210438/actors House Treasure of the Golden https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/treasure-of-the-golden-condor-3227913/actors Condor Return of the https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/return-of-the-texan-3428288/actors Texan Susan Slade https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/susan-slade-3505607/actors -

“Friends” Co-Creator Marta Kauffman to Produce “Hava Nagila” Documentary

Contact: Roberta Grossman 323.424.4210 [email protected] www.katahdin.org “FRIENDS” CO-CREATOR MARTA KAUFFMAN TO PRODUCE “HAVA NAGILA” DOCUMENTARY EMMY AWARD-WINNING PRODUCER RETEAMS WITH “BLESSED IS THE MATCH” FILMMAKERS TO EXPLORE THE HISTORY, MYSTERY AND MEANING OF THE ICONIC JEWISH SONG Hollywood, CA (January 27, 2011) – Emmy Award-winning producer Marta Kauffman is reteaming with her partners on the documentary Blessed Is the Match to bring the story of the iconic song “Hava Nagila” to the screen. Funny, deep and unexpected, Hava Nagila: What Is It? will celebrate 100 years of Jewish history and culture through the journey of a song, and reveal the power of music to bridge cultural divides and bring us together as human beings. “We are thrilled to be working with Marta again,” says director Roberta Grossman, whose film Blessed Is the Match, about Holocaust heroine Hannah Senesh, was shortlisted for an Academy Award, won the audience award at 13 film festivals, was broadcast on PBS in 2010, and nominated for a Primetime Emmy. “Marta is someone who elevates every project she touches, and her experience and guidance will only make the film better.” Kauffman was the co-creator and executive producer of the hit TV series Friends. Prior to her work on Friends, Kauffman co-created and co-executive produced the critically acclaimed series Dream On. She co-created the series The Powers That Be, for Norman Lear, and co-created and served as executive producer on the comedy series Family Album and Veronica’s Closet. Kauffman executive produced Blessed Is the Match, working closely with Grossman, producer Lisa Thomas and writer Sophie Sartain. -

GRIT Program Schedule Listings in Eastern Time

GRIT Program Schedule Listings in Eastern Time Week Of 07-09-2018 Grit 7/9 Mon 7/10 Tue 7/11 Wed 7/12 Thu 7/13 Fri 7/14 Sat 7/15 Sun Grit 06:00A Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC Movie: The Redhead And The Cowboy Movie: Westbound 06:00A 06:30A Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; CC TV-PG V; 1951 TV-PG V; 1959 06:30A CC CC 07:00A Death Valley Days: TV-PG L, V; CC Death Valley Days: TV-PG L, V; CC Death Valley Days: TV-PG L, V; CC Death Valley Days: TV-PG L, V; CC Death Valley Days: TV-PG L, V; CC 07:00A 07:30A Death Valley Days: TV-PG L, V; CC Death Valley Days: TV-PG L, V; CC Death Valley Days: TV-PG L, V; CC Death Valley Days: TV-PG; CC Death Valley Days: TV-PG L, V; CC Movie: Across The Wide Missouri 07:30A 08:00A The Life And Legend Of Wyatt Earp: The Life And Legend Of Wyatt Earp: The Life And Legend Of Wyatt Earp: The Life And Legend Of Wyatt Earp: The Life And Legend Of Wyatt Earp: Movie: Colt .45 TV-PG V; 1951 08:00A CC 08:30A TheTV-PG Life V; And CC Legend Of Wyatt Earp: TheTV-PG Life V; And CC Legend Of Wyatt Earp: TheTV-PG Life V; And CC Legend Of Wyatt Earp: TheTV-PG Life V; And CC Legend Of Wyatt Earp: TheTV-PG Life V; And CC Legend Of Wyatt Earp: TV-PG V; 1950 08:30A CC 09:00A TheTV-PG Life V; And CC Legend Of Wyatt Earp: TheTV-PG Life V; And CC Legend Of Wyatt -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

How Much Should Guests Expect to Spend This Wedding Season?

How Much Should Guests Expect to Spend This Wedding Season? Cost of attending weddings, bachelor/bachelorette parties and showers adds up fast NEW YORK – March 28, 2018 – Wedding guests should be prepared to spend hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars per celebration this wedding season, according to a new Bankrate.com report. This includes the cost of attending the wedding, as well as associated events like bachelor/bachelorette parties and wedding showers. Click here for more information: https://www.bankrate.com/personal-finance/smart-money/cost-of-attending-wedding-survey- 0318/ The most expensive commitment comes with being a part of the wedding party. Members of the wedding party can expect to spend an average of $728 on the wedding and related festivities of the bachelor/bachelorette party and wedding shower (including gifts, travel, attire and more). Northeastern wedding party members shell out even more than that, with an average all-in cost of $1,070 to partake in all three events. Attending a wedding for a close friend or family member when not part of the wedding party is not cheap, either. Guests attending those weddings and associated pre-parties spend an average of $628. Those attending weddings and related events for more distant friends/family members will experience some financial relief, comparatively, with a total average cost of $372. When it comes to gift-giving, Millennial guests (ages 18-37) seem to be less generous than the national average. Young adults report spending an average of just $57 on wedding gifts when part of the wedding party, $47 for close friends/family when not in the wedding party and $48 for more distant relationships. -

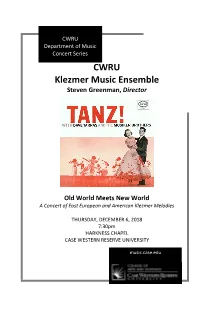

Klezmer Program 12.06.18

CWRU DepArtment oF MusIc Concert SerIes CWRU Klezmer Music Ensemble Steven Greenman, Director Old World Meets New World A Concert of East European and American Klezmer Melodies THURSDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2018 7:30pm HARKNESS CHAPEL CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY musIc.cAse.edu Welcome to Florence-Harkness Memorial Chapel RESTROOMS Women’s And men’s restrooms Are locAted on the mAIn level oF the buildIng. PAGERS, CELL PHONES, COMPUTERS, IPADS AND LISTENING DEVICES As A courtesy to the perFormers And AttendIng AudIence members, pleAse power oFF All electronic And mechanicAl devIces, Including pagers, cellulAr telephones, computers IPAds, wrIst wAtch AlArms, etc. prIor to the stArt oF the concert. PHOTOGRAPHY, VIDEO AND RECORDING DEVICES As A courtesy to the perFormers And AudIence members, photogrAphy And vIdeogrAphy Is strIctly prohibIted durIng the perFormAnce. FACILITY GUIDELINES In order to preserve the beAuty And cleAnlIness oF the hAll, no Food or beverAge, Including wAter, Is permItted. A DrInkIng FountAIn Is locAted neAr the restrooms beside the classroom. IN THE EVENT OF AN EMERGENCY ContAct An usher or A member oF the house stAFF IF you requIre medIcAl AssIstAnce. Emergency exIts Are cleArly marked throughout the buIldIng. Ushers And house staFF wIll provIde Instruction In the event oF An emergency. musIc.cAse.edu/FAcIlItIes/Florence-harkness-memorIAl-chApel/ Program “Rumania” Bulgar AlexAnder OlshAnetsky -from the recordIng Tanz! With Dave Tarras and the Musiker Brothers - 1955 Chused’l #10 from International HeBrew Wedding Music (“HAsIdIc DAnce #10) by W. KostAkowsky - 1916 Dem Trisker Rebn’s Khosid TrAdItIonAl/DAve TArrAs (“The TrIsker Rebbe’s DAnce”) Recorded - 1925 Yiddish Bulgar Max EpsteIn (“JewIsh BulgAr”) Recorded wIth the HymIe JAcobson OrchestrA - 1947 Romanian Fantasy Pt. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 77, 1957-1958, Subscription

*l'\ fr^j BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON 24 G> X will MIIHIi H tf SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1957-1958 BAYARD TUCEERMAN. JR. ARTHUR J. ANDERSON ROBERT T. FORREST JULIUS F. HALLER ARTHUR J. ANDERSON, JR. HERBERT 8. TUCEERMAN J. DEANE SOMERVILLE It takes only seconds for accidents to occur that damage or destroy property. It takes only a few minutes to develop a complete insurance program that will give you proper coverages in adequate amounts. It might be well for you to spend a little time with us helping to see that in the event of a loss you will find yourself protected with insurance. WHAT TIME to ask for help? Any time! Now! CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. RICHARD P. NYQUIST in association with OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description 108 Water Street Boston 6, Mast. LA fayette 3-5700 SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1957-1958 Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor CONCERT BULLETIN with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk Copyright, 1958, by Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Jacob J. Kaplan Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Talcott M. Banks Michael T. Kelleher Theodore P. Ferris Henry A. Laughlin Alvan T. Fuller John T. Noonan Francis W. Hatch Palfrey Perkins Harold D. Hodgkinson Charles H. Stockton C. D. Jackson Raymond S. Wilkins E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Oliver Wolcott TRUSTEES EMERITUS Philip R. Allen M. A. DeWolfe Howe N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Edward A. Taft Thomas D. -

American Folk Music and Folklore Recordings 1985: a Selected List

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 277 618 SO 017 762 TITLE American Folk Music and Folklore Recordings 1985: A Selected List. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. American Folklife Center. PUB DATE 86 NOTE 17p.; For the recordings lists for 1984 and 1983, see ED 271 353-354. Photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROM Selected List, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20540. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Black Culture; *Folk Culture; *Jazz; *Modernism; *Music; Popular Culture ABSTRACT Thirty outstanding records and tapes of traditional music and folklore which were released in 1985 are described in this illustrated booklet. All of these recordings are annotated with liner notes or accompanying booklets relating the recordings to the performers, their communities, genres, styles, or other pertinent information. The items are conveniently available in the United States and emphasize "root traditions" over popular adaptations of traditional materials. Also included is information about sources for folk records and tapes, publications which list and review traditional music recordings, and relevant Library of Congress Catalog card numbers. (BZ) U.111. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office or Educao onal Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) This document hes been reproduced u received from the person or o•panizahon originating it Minor changes nave been made to improve reproduction ought) Points of view or opinions stated in this docu mint do not necessarily represent Olhcrai OERI posrtio.r or policy AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC AND FOLKLORE RECORDINGS 1985 A SELECTED LIST Selection Panel Thomas A. Adler University of Kentucky; Record Review Editor, Western Folklore Ethel Raim Director, Ethnic Folk Arts Center Don L. -

Film. It's What Jews Do Best. Aprll 11-21 2013 21ST

21ST TORONTO JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL APRIL 11-21 2013 WWW.TJFF.COM FILM. It’S WHAT JEWS DO BEST. DRAMAS OVERDRIVE AD COMEDIES DOCUMENTARIES BIOGRAPHIES ARCHIVAL FILMS ARCHIVAL SHORT FILMS SHORT Proudly adding a little spark to the Toronto Jewish Film Festival since 2001. overdrivedesign.com 2 Hillel Spotlight on Israeli Films Spotlight on Africa Israel @ 65 Free Ticketed Programmes CONTENTS DRAMAS 19 COMEDIES 25 DOCUMENTARIES 28 BIOGRAPHIES 34 ARCHIVAL FILMS 37 SHORT FILMS 38 4 Schedule 15 Funny Jews: 7 Comedy Shorts 42 Patron Circle 6 Tickets 15 REEL Ashkenaz @ TJFF 43 Friends and Fans 7 Artistic Director’s Welcome 16 Talks 44 Special Thanks 8 Co-Chairs’ Message 17 Free Family Screenings 44 Nosh Donors 9 Programme Manager’s Note 18 Opening / Closing Night Films 44 Volunteers 10 Programmers’ Notes 19 Dramas 46 Sponsors 12 David A. Stein Memorial Award 25 Comedies 49 Advertisers 13 FilmMatters 28 Documentaries 67 TJFF Board Members and Staff 13 Hillel Spotlight on Israeli Film 34 Biographies 68 Films By Language 14 Spotlight on Africa 37 Archival Films 70 Films By Theme / Topic 14 Israel @ 65 38 Short Films 72 Film Index APRIL 11–21 2013 TJFF.COM 21ST ANNUAL TORONTO JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL 3 SCHEDULE • Indicates film has additional screening(s).Please Note: Running times do not include guest speakers where applicable. Thursday April 11 Monday April 15 8:30 PM BC 92 MIN CowJews and Indians: How Hitler 1:00 PM ROM 100 MIN • Honorable Ambassador w/ Delicious Scared My Relatives and I Woke up Peace Grows in a Ugandan in an Iroquois Longhouse —Owing