Toby Rush—Music Theory for Musicians and Normal People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naming a Chord Once You Know the Common Names of the Intervals, the Naming of Chords Is a Little Less Daunting

Naming a Chord Once you know the common names of the intervals, the naming of chords is a little less daunting. Still, there are a few conventions and short-hand terms that many musicians use, that may be confusing at times. A few terms are used throughout the maze of chord names, and it is good to know what they refer to: Major / Minor – a “minor” note is one half step below the “major.” When naming intervals, all but the “perfect” intervals (1,4, 5, 8) are either major or minor. Generally if neither word is used, major is assumed, unless the situation is obvious. However, when used in naming extended chords, the word “minor” usually is reserved to indicate that the third of the triad is flatted. The word “major” is reserved to designate the major seventh interval as opposed to the minor or dominant seventh. It is assumed that the third is major, unless the word “minor” is said, right after the letter name of the chord. Similarly, in a seventh chord, the seventh interval is assumed to be a minor seventh (aka “dominant seventh), unless the word “major” comes right before the word “seventh.” Thus a common “C7” would mean a C major triad with a dominant seventh (CEGBb) While a “Cmaj7” (or CM7) would mean a C major triad with the major seventh interval added (CEGB), And a “Cmin7” (or Cm7) would mean a C minor triad with a dominant seventh interval added (CEbGBb) The dissonant “Cm(M7)” – “C minor major seventh” is fairly uncommon outside of modern jazz: it would mean a C minor triad with the major seventh interval added (CEbGB) Suspended – To suspend a note would mean to raise it up a half step. -

05/08/2007 Trevor De Clercq TH521 Laitz

05/08/2007 Trevor de Clercq TH521 Laitz Harmony Lecture (topic: introduction to modal mixture; borrowed chords; subtopic: mixture in a major key [^b6, ^b3, ^b7]) (N.B. I assume that students have been taught on a track equivalent to that of The Complete Musician, i.e. they will have had exposure to applied chords, tonicization, modulation, but have not yet been exposed to the Neapolitan or Augmented Sixth chord) I. Introduction to concept A. Example of primary mixture in major mode (using ^b6) 1. First exposure (theoretical issue) • Handout score to Chopin excerpt (Waltz in A minor, op. 34, no. 2, mm. 121-152) • Play through the first half of the Chopin example (mm. 121-136) • Ask students what key the snippet of mm. 121-136 is in and how they can tell • Remark that these 16 bars, despite being clearly in A major, contain a lot of chromatic notes not otherwise found in A major • Work through (bar by bar with students providing answers) the chromatic alterations in mm. 121-131, all of which can be explained as either chromatic passing notes or members of applied harmonies • When bar 132 is reached, ask students what they think the purpose of the F-natural and C- natural alterations are (ignore the D# on the third beat of bar 132 for now) • Point out the parallel phrase structure between mm. 121-124 and mm. 129-132, noting that in the first case, the chord was F# minor, while in the second instance, it is F major • Remark that as of yet in our discussion of music theory, we have no way of accounting for (or labeling) an F major chord in A major; the former doesn't "belong" to the latter 2. -

Discover Seventh Chords

Seventh Chords Stack of Thirds - Begin with a major or natural minor scale (use raised leading tone for chords based on ^5 and ^7) - Build a four note stack of thirds on each note within the given key - Identify the characteristic intervals of each of the seventh chords w w w w w w w w % w w w w w w w Mw/M7 mw/m7 m/m7 M/M7 M/m7 m/m7 d/m7 w w w w w w % w w w w #w w #w mw/m7 d/wm7 Mw/M7 m/m7 M/m7 M/M7 d/d7 Seventh Chord Quality - Five common seventh chord types in diatonic music: * Major: Major Triad - Major 7th (M3 - m3 - M3) * Dominant: Major Triad - minor 7th (M3 - m3 - m3) * Minor: minor triad - minor 7th (m3 - M3 - m3) * Half-Diminished: diminished triad - minor 3rd (m3 - m3 - M3) * Diminished: diminished triad - diminished 7th (m3 - m3 - m3) - In the Major Scale (all major scales!) * Major 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 2, 3, 6 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 - In the Minor Scale (all minor scales!) with a raised leading tone for chords on ^5 and ^7 * Major 7th on scale degrees 3 & 6 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 2 * Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 Using Roman Numerals for Triads - Roman Numeral labels allow us to identify any seventh chord within a given key. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth Chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen Chords Sometimes Referred to As Chords with 'Extensions', I.E

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen chords sometimes referred to as chords with 'extensions', i.e. extending the seventh chord to include tones that are stacking the interval of a third above the basic chord tones. These chords with upper extensions occur mostly on the V chord. The ninth chord is sometimes viewed as superimposing the vii7 chord on top of the V7 chord. The combination of the two chord creates a ninth chord. In major keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a whole step above the root (plus octaves) w w w w w & c w w w C major: V7 vii7 V9 G7 Bm7b5 G9 ? c ∑ ∑ ∑ In the minor keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a half step above the root (plus octaves). In chord symbols it is referred to as a b9, i.e. E7b9. The 'flat' terminology is use to indicate that the ninth is lowered compared to the major key version of the dominant ninth chord. Note that in many keys, the ninth is not literally a flatted note but might be a natural. 4 w w w & #w #w #w A minor: V7 vii7 V9 E7 G#dim7 E7b9 ? ∑ ∑ ∑ The dominant ninth usually resolves to I and the ninth often resolves down in parallel motion with the seventh of the chord. 7 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ & ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ C major: V9 I A minor: V9 i G9 C E7b9 Am ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ? ˙ ˙ The dominant ninth chord is often used in a II-V-I chord progression where the II chord˙ and the I chord are both seventh chords and the V chord is a incomplete ninth with the fifth omitted. -

Download Music Theory IV Syllabus 2018

MUSC 212 Prof. Tim Tollefson Music Theory IV Office: YFAC 206 Spring, 2018 [email protected] MWF 10:30-11:20 AM Office Phone: 382 Course Description This is the final course in a series (MUSC 111, 112, 211, and 212) that is designed to give the student a firm grasp of the concepts and practices commonly found in Western art music. Music of the 19th and 20th centuries will be the primary focus. Contemporary music (late 20th century and early 21st century) will also be discussed, although not in as much detail. The initial focus will be on the increased use of chromaticism and enharmonic chords, and then later we will study some of the new methods of music composition that came to the fore when the traditional tonal system broke down. This course supports the music department's overall objective for music theory, composition and music skills, which reads as follows: Students will be able to create, manipulate and analyze musical structures typical of the major historical periods, utilizing the many elements of musical language such as melody, harmony, rhythm, form, timbre, and notation. (Program Learning Outcome 1) Learning Outcomes for Music Theory IV: A student who gets an “A” in this course will be able to: --explain the numerous musical terms covered in the course --do a Roman numeral analysis of musical compositions involving the various types of chords covered in Music Theory I-IV --label embellishing tones in a tonal composition --recognize, create and use doubly augmented 4th chords, enharmonic diminished 7ths, enharmonic German -

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications Minseon Song May 17, 2014 Abstract Transformational theory is a modern branch of music theory developed by David Lewin. This theory focuses on the transformation of musical objects rather than the objects them- selves to find meaningful patterns in both tonal and atonal music. A generalized interval system is an integral part of transformational theory. It takes the concept of an interval, most commonly used with pitches, and through the application of group theory, generalizes beyond pitches. In this paper we examine generalized interval systems, beginning with the definition, then exploring the ways they can be transformed, and finally explaining com- monly used musical transformation techniques with ideas from group theory. We then apply the the tools given to both tonal and atonal music. A basic understanding of group theory and post tonal music theory will be useful in fully understanding this paper. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 A Crash Course in Music Theory 2 3 Introduction to the Generalized Interval System 8 4 Transforming GISs 11 5 Developmental Techniques in GIS 13 5.1 Transpositions . 14 5.2 Interval Preserving Functions . 16 5.3 Inversion Functions . 18 5.4 Interval Reversing Functions . 23 6 Rhythmic GIS 24 7 Application of GIS 28 7.1 Analysis of Atonal Music . 28 7.1.1 Luigi Dallapiccola: Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera, No. 3 . 29 7.1.2 Karlheinz Stockhausen: Kreuzspiel, Part 1 . 34 7.2 Analysis of Tonal Music: Der Spiegel Duet . 38 8 Conclusion 41 A Just Intonation 44 1 1 Introduction David Lewin(1933 - 2003) is an American music theorist. -

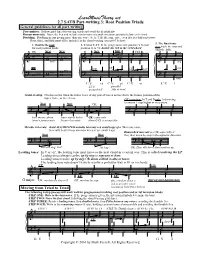

Root Position Triads Part-Writing

LearnMusicTheory.net 2.7 SATB Part-writing 3: Root Position Triads General guidelines for all part-writing Prerequisites. Follow guidelines for voicing triads and avoid the fiendish five. Roman numerals: Name the key and include roman numerals with inversion symbols below each chord. Doubling: Doubling means giving more than one voice (S, A, T, B) the same note, even if it is a different octave. Root, third, and fifth must all be included in the chord voicing (except #3 below). 3. The final tonic 1. Double the root 2. V-vi or V-VI: In the progression root position V to root may triple the root and for root position triads. position vi or VI, double the 3rd in the vi/VI chord. omit the fifth. OK NO! NO! NO! NO! YES 3rd! root root 5th! 3rd! 3rd LT! LT LT 3rd! root 5th! 3rd! root root C:V vi C:V vi C:V vi C:V I LT is parallel unresolved! 5ths & 8ves! Avoid overlap. Overlap occurs when the lower voice of any pair of voices moves above the former position of the upper voice, or vice-versa. OK exception: In T and B only, 3rd moving to unison 1 step higher or vice-versa NO! NO! OK bass moves above tenor moves below OK: same note tenor's former note former bass note (here C-C) is acceptable Melodic intervals: Avoid AUGMENTED melodic intervals and avoid leaps of a 7th in one voice. Generally best to keep common tones or use small leaps. Diminished intervals are OK, especially if NO! NO! they then move by step in the opposite direction. -

A Study of Compositional Elements in Ciclo Brasileiro by Heitor Villa- Lobos

A STUDY OF COMPOSITIONAL ELEMENTS IN CICLO BRASILEIRO BY HEITOR VILLA- LOBOS Maria Eduarda Lucena Vieira A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2017 Committee: Gene Trantham, Advisor Yu-Lien The ii ABSTRACT Gene Trantham, Advisor Heitor Villa-Lobos, a well-known Brazilian composer, was born in the city of Rio de Janeiro, in 1887, the same place where he died, in 1959. He was influenced by many composers not only from Brazil, but also from around the world, such as Debussy, Igor Stravinsky and Darius Milhaud. Even though Villa-Lobos spent most of his life traveling to Europe and the United States, his works always had a Brazilian musical flavor. This thesis will focus on the Ciclo Brasileiro (Brazilian Cycle) written for piano in 1936. The premiere of this set was initially presented in 1938 as individual pieces including “Impressões Seresteiras” (The Impressions of a Serenade) and “Dança do Indio Branco” (Dance of the White Indian). The other pieces of the set, “Plantio do Caboclo” (The Peasant’s Sowing) and “Festa no Sertão” (The Fete in the Desert) were premiered in 1939. Both performances occurred in Rio de Janeiro. Also in 1936 he wrote two other pieces, “Bazzum”, for men’s voices and Modinhas e canções (Folk Songs and Songs), album 1. My thesis will explore Heitor Villa-Lobos’ Ciclo Brasileiro and hopefully will find direct or indirect elements of the Brazilian culture. In chapter 1, I will present an introduction including Villa-Lobos’ background about his life and music, and how classical and folk influences affected his compositional process in the Ciclo Brasileiro. -

AP Music Theory Syllabus

AP Music Theory Syllabus Course Overview This rigorous course expands upon the skills learned in the choral and instrumental courses offered at our school. Musical composition, sequencing, and Finale software use are some of the many applications employed to further student understanding of music theory. Objectives of the Course This course is designed to develop musical skills that will lead to a thorough understanding of music composition and music theory. Students are prepared to take the AP* Music Theory Exam when they have completed the course. Students planning to major in music in college may be able to enroll in an advanced music theory course, depending on individual colleges’ AP policies. General Course Content 1. Review of music fundamentals, including: scales, key signatures, circle-of-fifths, intervals triads and inversions 2. Daily ear training, including rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic dictation 3. Weekly Sight-Singing using numbers and solfege for pitches 4. The study of modes 5. The study of figured bass 6. The study of two-part counterpoint 7. The study of four-part harmony 8. The study of seventh chords 9. The study of secondary-dominant functions 10. The study of musical form 11. The study of common compositional techniques The objectives below have been adapted from the Expanded Course Specifications posted on the AP Music Theory Home Page on AP Central Expanded Course Objectives 1. Identify and notate pitch in four clefs: treble, bass, alto and tenor. 2. Notate, hear and identify simple and compound meters. 3. Notate and identify all major and minor key signatures. 4. Notate, hear and identify the following scales: chromatic, major and the three minor forms. -

Graduate Music Theory Exam Preparation Guidelines

Graduate Theory Entrance Exam Information and Practice Materials 2016 Summer Update Purpose The AU Graduate Theory Entrance Exam assesses student mastery of the undergraduate core curriculum in theory. The purpose of the exam is to ensure that incoming graduate students are well prepared for advanced studies in theory. If students do not take and pass all portions of the exam with a 70% or higher, they must satisfactorily complete remedial coursework before enrolling in any graduate-level theory class. Scheduling The exam is typically held 8:00 a.m.-12:00 p.m. on the Thursday just prior to the start of fall semester classes. Check with the Music Department Office for confirmation of exact dates/times. Exam format The written exam will begin at 8:00 with aural skills (intervals, sonorities, melodic and harmonic dictation) You will have until 10:30 to complete the remainder of the written exam (including four- part realization, harmonization, analysis, etc.) You will sign up for individual sight-singing tests, to begin directly after the written exam Activities and Skills Aural identification of intervals and sonorities Dictation and sight-singing of tonal melodies (both diatonic and chromatic). Notate both pitch and rhythm. Dictation of tonal harmonic progressions (both diatonic and chromatic). Notate soprano, bass, and roman numerals. Multiple choice Short answer Realization of a figured bass (four-part voice leading) Harmonization of a given melody (four-part voice leading) Harmonic analysis using roman numerals 1 Content -

Musiciansfor Normaland

MUSIC THEORY MUSICIANSfor NORMALand “My Dad” Sofia Rush, Age 5 Pen and crayon on printer paper realPEOPLE college-level music theory, from fundamental concepts to advanced concepts presented in a convenient, fun, engaging and thorough one-topic-per-page format free to copy, for more, visit share and enjoy! by Toby W. Rush tobyrush.com music theory for musicians and normal people by toby w. rush so then the What is Music Theory? bassoon choir comes in like flaming Chances are there’s a piece of music honeydew melons that moves you in a profound way... from on high a way that is frustratingly difficult to describe to someone else! Like other forms of art, music often has the capability to create in the listener that emotional reactions please transcends other forms of communication. bradley it’s late though a single piece of music may elicit different reactions from different listeners, any and if i’m lover of music will tell you that they’re real, almost those feelings are real! they’re worthy done of study. one of the most valuable parts coming up with terminology of music theory is giving names to doesn’t just help us talk to musical structures and processes, others about music, though... which makes them easier to talk about! it actually helps us learn! but while it’s an important step, and a great place to start, music theory is much more than just coming up with names for things! when composers write music — whether it’s a classical- era symphony or a bit of japanese post-shibuya-kei glitch techno — they are not following a particular set of rules.