Complicating Diasporic Negritude

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions

Scholars Crossing History of Global Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions" (2009). History of Global Missions. 3. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Global Missions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Middle Ages 500-1000 1 3 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions AD 500—1000 Introduction With the endorsement of the Emperor and obligatory church membership for all Roman citizens across the empire, Roman Christianity continued to change the nature of the Church, in stead of visa versa. The humble beginnings were soon forgotten in the luxurious halls and civil power of the highest courts and assemblies of the known world. Who needs spiritual power when you can have civil power? The transition from being the persecuted to the persecutor, from the powerless to the powerful with Imperial and divine authority brought with it the inevitable seeds of corruption. Some say that Christianity won the known world in the first five centuries, but a closer look may reveal that the world had won Christianity as well, and that, in much less time. The year 476 usually marks the end of the Christian Roman Empire in the West. -

Rosaria Munson April 4Th, 1992 Half a Man's Worth": Popular Ideology

������������������������������ Half a Man's Worth": Popular Ideology about Slavery in Democratic Athens We see slavery as incompatible with democracy; the Athenians did not. What was their justification? Since slaves were not part of the polis, there is little coverage in our sources, but we can at least see what Athenians of the 5th and 4th centuries said about the institution of slavery and slaves. Homer's comment (via Odysseus' faithful slave Eumaeus) that "Zeus takes away half of a man's ����� (worth or excellence) once the day of slavery comes upon him" is the first explicit statement of the moral inferiority of a slave, though it is striking that the speaker is himself a slave who embodies ������ (nobleness, bravery). There was a universal acceptance of slavery as existing from the very beginning, but chattel slavery in Athens was relatively recent. As the rights of aristocrats spread in Athens to the middle and even lower classes, slaves increasingly filled the menial tasks, including public services, such as police, bookkeeping, cleaning the city. There were three or four private slaves per household, as domestics, farm laborers, or industrial laborers (used by the owner himself or rented out). A few rich men owned numerous slaves. Most rich men would have owned about fifty, but even the most modest household would have at least one. An Athenian without a slave (or the money to buy a slave - about the same price as a mule) argues in one text that he ought to get public assistance. Manumission was infrequent and slaves were treated much differently than free: a slave witness can give evidence only under torture since a slave cannot be trusted to tell the truth - especially against his master - except through torture. -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Sara Martín Alegre P08/04540/02135 © FUOC • P08/04540/02135 Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 7 1. Literature 1945-1990: cultural context........................................ 9 1.1. The book market in Britain ........................................................ 9 1.2. The relationship between Literature and the universities .......... 10 1.3. Adaptations of literary works for television and the cinema ...... 11 1.4. The minorities in English Literature: women and post-colonial writers .................................................................... 12 2. The English Novel 1945-1990.......................................................... 14 2.1. Traditionalism: between the past and the present ..................... 15 2.2. Fantasy, realism and experimentalism ........................................ 16 2.3. The post-modern novel .............................................................. 18 3. Drama in England 1945-1990......................................................... 21 3.1. West End theatre and the new English drama ........................... 21 3.2. Absurdist drama and social and political drama ........................ 22 3.3. New theatre companies and the Arts Council ............................ 23 3.4. Theatre from the mid-1960s onwards ....................................... -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case 2:18-cv-10417 Document 1 Filed 12/17/18 Page 1 of 24 Page ID #:1 1 Pierce Bainbridge Beck Price & Hecht LLP John M. Pierce (SBN 250443) 2 [email protected] 3 Carolynn Kyungwon Beck (SBN 264703) [email protected] 4 Daniel Dubin (SBN 313235) 5 [email protected] 600 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 500 6 Los Angeles, California 90017-3212 7 (213) 262-9333 8 Attorneys for 9 Plaintiff Alfonso Ribeiro 10 THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 11 FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 12 Alfonso Ribeiro, an Case No. 2:18-cv-10417 13 individual, 14 Complaint for: Plaintiff, 15 1. Direct Infringement of v. 16 Copyright; 17 Take-Two Interactive 2. Contributory Infringement Software, Inc.; a Delaware of Copyright; 18 corporation; 2K Sports, Inc., a 3. Violation of the Right of 19 Delaware corporation; 2K Publicity under California Games, Inc., a Delaware Common Law; 20 corporation; Visual Concepts 4. Violation of the Right of 21 Entertainment, a California Publicity under Cal. Civ. 22 Corporation; and Does 1 Code § 3344; through 50, inclusive, 5. Unfair Competition under 23 Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 24 Defendants. 17200, et seq.; 6. Unfair Competition under 25 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a) 26 Demand for Jury Trial 27 28 Complaint Case 2:18-cv-10417 Document 1 Filed 12/17/18 Page 2 of 24 Page ID #:2 1 Plaintiff Alfonso Ribeiro, aka Ribeiro, (“Plaintiff” or “Ribeiro”), by 2 and through his undersigned counsel, asserts the following claims 3 against Defendants Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. (“Take-Two”), 4 2K Sports, Inc. -

A Rhetorical Study of Edward Abbey's Picaresque Novel the Fool's Progress

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2001 A rhetorical study of Edward Abbey's picaresque novel The fool's progress Kent Murray Rogers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Rogers, Kent Murray, "A rhetorical study of Edward Abbey's picaresque novel The fool's progress" (2001). Theses Digitization Project. 2079. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RHETORICAL STUDY OF EDWARD ABBEY'S PICARESQUE NOVEL THE FOOL'S PROGRESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Kent Murray Rogers June 2001 A RHETORICAL STUDY OF EDWARD ABBEY'S PICARESQUE NOVEL THE FOOL,'S PROGRESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Kent Murray Rogers June 2001 Approved by: Elinore Partridge, Chair, English Peter Schroeder ABSTRACT The rhetoric of Edward Paul Abbey has long created controversy. Many readers have embraced his works while many others have reacted with dislike or even hostility. Some readers have expressed a mixture of reactions, often citing one book, essay or passage in a positive manner while excusing or completely .ignoring another that is deemed offensive. -

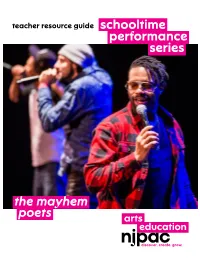

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

The Fragmentation of Imagism It Was 1912, and a New Mode of Poetry Was Taking Root

The Fragmentation of Imagism It was 1912, and a new mode of poetry was taking root. Sparked by the ideas of T.E. Hulme and from distaste of the drippy sentimentalism of the Romantic era (Britannica “Imagist”), Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, and H.D. literally wrote the rules of Imagism. Their dry, concise look at an image or “complex,” as Pound described it, helped lay the foundation for modernist poetry. However, the Imagists’ granite rules could not ensure strict adherence to their form, not even from founding members of Imagism themselves. As the years went by, the Imagists themselves grew weary of their own form by both their own admittance and through their later works. Ezra Pound was the first leader of the Imagist movement, and his autocratic grip on the concept of Imagism may be partly to blame for the fragmentation of the movement. Pound makes it quite clear that, “At least for myself, I want [twentieth-century poetry] so, austere, direction, free from emotional slither (“A Retrospect” 23).” He carefully selected and edited poems for published volumes of Imagist poetry, but the appearance of the popular and wealthy poet heiress Amy Lowell swept in a new democratic format for the group’s publications. Authors were to select what they considered their best work, without the stamp of approval from Pound deeming it true to the Imagist credo (Bradshaw 159). Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound clashed quite famously over the direction Imagism would take, as seen in Lowell’s poem to Pound, harshly dubbed “Astigmatism.” The poem pulls no punches; the analogy is clear in Lowell’s image of the Poet smashing lovely flowers of all kinds, saying “They are useless. -

Modern Problems Require Modern Solutions*: Internet Memes and Copyright

MATALON.PRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 12/21/2019 11:08 AM Modern Problems Require Modern Solutions*: Internet Memes and Copyright Lee J. Matalon** That which hath been is that which shall be, And that which hath been done is that which shall be done; And there is nothing new under the sun.1 Introduction In late 2018, a lawsuit was filed against Epic Games, creator of the smash-hit video game Fortnite Battle Royale.2 The plaintiff was Alfonso Ribeiro, known for playing Carlton Banks in the hit 1990s sitcom, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.3 Ribeiro asserted copyright claims against Epic for using digital representations of his “signature” dance, the “Carlton Dance,”4 as a player character “emote” in its game.5 Ribeiro alleged that “Epic creates emotes by copying and coding dances and movements directly from popular videos, movies, and television shows without consent.”6 His complaint also commented on the general popularity of the dance: “The Dance ha[d] garnered over sixty-nine million views on YouTube” prior to the release of Fortnite;7 and since its release, “[p]rofessional athletes . have based their celebrations on Fortnite emotes” and “[y]oung adults, teenagers, and kids * Modern Problems Require Modern Solutions, KNOW YOUR MEME, https:// knowyourmeme.com/memes/modern-problems-require-modern-solutions [https://perma.cc /CG6Y-VLPB] (last updated Feb. 4, 2019, 6:04 AM). ** Notes Editor, Volume 98, Texas Law Review. J.D. Candidate, Class of 2020, The University of Texas School of Law. My thanks go to Professor Oren Bracha for his excellent instruction and his helpful comments on earlier drafts of this Note. -

SURREALISM IS a THING RUBRICS and OBJECTIVATION in the SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine Hansen

ARTICLE Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/5/3/62/1832938/artm_a_00158.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 SURREALISM IS A THING RUBRICS AND OBJECTIVATION IN THE SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine hansen What Will Be is the title of a 2014 anthology compiled by members of a 21st-century international network of Surrealist groups, announcing the continuing ambitions of a movement that fi rst began amid the sleeping fi ts and Dada-inspired provocations of the early 1920s. The anthology includes a special feature on the publishing activities of the various groups, which frequently coordinate their efforts across group and national boundaries—operating as a kind of dispersed organism whose vital functions have never seen fi t to cease, even as Surrealism has come to be considered a historical and concluded phenomenon. There is particular emphasis on the Surrealist attitude, in general, toward publishing, publicization, circulation, the digital revolution, and the rise of on-demand printing. Contributors, for example, speak- ing on behalf of the Montreal- and Miami-based Surrealist publisher Editions Sonámbula, state: “any attempt aiming to expand the fi eld of the real and of the poetic has necessarily to refl ect on the means of communication to use.”1 Surrealism has always claimed to extend the domain of what is 1 “The Utility of Surrealist Editions and of the Surrealist Gallery: An Inquiry,” in Ce qui sera/What Will Be/Lo que serà: Almanac of the International Surrealist Movement, “hors- série” number of Brumes Blondes, ed. Her de Vries and Laurens Vancrevel (Amsterdam: Brumes Blondes, 2014), 438–39. -

BFI SOUTHBANK EVENTS LISTINGS for JUNE 2017 PREVIEWS Catch the Latest Film and TV Alongside Q&As and Special Events Preview

BFI SOUTHBANK EVENTS LISTINGS FOR JUNE 2017 PREVIEWS Catch the latest film and TV alongside Q&As and special events Preview: Churchill + Q&A with filmmakers and cast UK 2017. Dir Jonathan Teplitzky. With Brian Cox, Miranda Richardson, John Slattery, James Purefoy. 110min. Digital. Cert TBC. Courtesy of Lionsgate A glimpse behind the icon and into the personality and pressures faced by one of history’s most important political figures. This gripping, tightly-scripted thriller focuses on Winston Churchill (Cox) in the run-up to D- Day, as he battles with the overwhelming responsibility of sending the Allied Forces to retake Nazi-occupied Europe. Exhausted and depressed, Churchill is terrified of leaving behind a legacy of carnage, and must face political opponents as well as his own demons. Tickets £15, concs £12 (Members pay £2 less) MON 5 JUN 19:00 NFT1 Preview: Hounds of Love Australia 2016. Dir Ben Young. With Emma Booth, Ashleigh Cummings, Stephen Curry. 108min. Digital. Cert TBC. Courtesy of Arrow Films In a sweltering 1987 Christmas in Perth, something is threatening the sleepy suburban streets. Sadistic couple John and Evelyn White (Curry and Booth) randomly abduct Vicki Maloney (Cummings), the latest of their victims. Chained and tortured, the teenager soon realises she needs to drive a wedge between her captors if she wants to survive. Australian writer-director Ben Young makes an assured debut in this tightly woven thriller inspired by an infamous real-life case, elevating the disturbing material into a lesson in suspenseful storytelling. Not for the faint-hearted, bold viewers will be rewarded with a chilling spin on the serial-killer genre. -

William Shakespeare and Chinua Achebe: a Study of Character and the Supernatural

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2010 William Shakespeare and Chinua Achebe: A Study of Character and the Supernatural Kenneth N. Usongo University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Usongo, Kenneth N., "William Shakespeare and Chinua Achebe: A Study of Character and the Supernatural" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1387. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1387 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE AND CHINUA ACHEBE: A STUDY OF CHARACTER AND THE SUPERNATURAL __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Kenneth N. Usongo June 2011 Advisor: Linda Bensel-Meyers ©Copyright by Kenneth N. Usongo 2011 All Rights Reserved Author: Kenneth N. Usongo Title: WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE AND CHINUA ACHEBE: A STUDY OF CHARACTER AND THE SUPERNATURAL Advisor: Linda Bensel-Meyers Degree Date: June 2011 Abstract This study examines how Shakespeare and Achebe use supernatural devices such as prophecies, dreams, beliefs, divinations and others to create complex characters. Even though these features are indicative of the preponderance of the belief in the supernatural by some people of the Elizabethan, Jacobean and traditional Igbo societies, Shakespeare and Achebe primarily use the supernatural to represent the states of mind of their protagonists.