Richard Brettell Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UT Dallas' Dr Richard Brettell to Become New TDMN Visual Arts

MEDIA CONTACT Kerri Fulks (972) 499-6617 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sept. 16, 2013 The Dallas Morning News Appoints UT Dallas’ Chair of Arts & Aesthetics as Visual Arts Critic (DALLAS) – The Dallas Morning News, and its comprehensive entertainment resource GuideLive, has made another important move for its readers active in the arts and culture community by hiring Dr. Richard Brettell as its full-time Visual Arts Critic. Brettell will remain in his position as the Margaret M. McDermott Distinguished Chair of Art and Aesthetic Studies at University of Texas at Dallas (UT Dallas). Brettell will become the face and voice for one of the most prominent and discerning audiences in North Texas. As visual arts critic, he will create stories on a regular basis for the Arts & Life section, GuideLive’s ArtsBlog and a major piece every two months for the Morning News. “For the past 30 years, art has become my career, my muse and my passion,” said Brettell. “This is a great opportunity and responsibility to be honored as visual arts critic for one of the most artistically diverse cities in the United States. I look forward to establishing a larger presence for artists across North Texas, all of whom deserve more recognition and I am thrilled to provide that exposure.” Brettell began his focus on art in 1971 at Yale University where he earned a B.A., an M.A. and a Ph.D. His first job out of college was as an academic program director and assistant professor at the University of Texas in Austin for its art department. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Richard Robson Brettell, Ph.D. School of Arts and Humanities Margaret McDermott Distinguished Chair Arts & Aesthetics The University of Texas at Dallas 800 West Campbell Road Richardson, TX 75080-3021 973-883-2475 Education: Yale University, B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. (1971,1973,1977) Employment: Margaret McDermott Distinguished Chair of Art and Aesthetics, The University of Texas at Dallas, 1998- Independent Art Historian and Museum Consultant, 1992- American Director, FRAME, French Regional & American Museum Exchange, 1999- McDermott Director, The Dallas Museum of Art, 1988-1992 Searle Curator of European Painting, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1980-1988 Academic Program Director/Assistant Professor, Art History, Art Department, The University of Texas, Austin, 1976-1980 Other Teaching: Visiting Professor, Fine Arts Harvard University, spring term, 1995 Visiting Professor, The History of Art, Yale University, spring term, 1994 Adjunct Professor of Art History The University of Chicago, 1982-88 Visiting Instructor, Northwestern University, 1985 Fellowships: Visiting Scholar, The Clark Art Institute, Summers of 1996-2000 Visiting Fellow The Getty Museum, 1985 National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Fellow, 1980 Professional Affiliations: Chairman (1990) and Member, The United States Federal Indemnity Panel, 1987-1990 The Getty Grant Program Publication Committee 1987-1991 The American Association of Museum Directors 1988-93 The Elizabethan Club The Phelps Association Boards: FRAME (French Regional American Museum Exchange) Trustee 2010- The Dallas Architecture Forum, 1997-2004 (Founder and first president) The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation 1989-1995 Dallas Artists Research and Exhibitions, 1990- (founder and current president) The College Art Association 1986-9 Museum of African-American Life and Culture, 1988-1992 The Arts Magnet High School, Dallas, Texas, 1990-1993 Personal Recognition: Dr. -

Linda Ridgway

Linda Ridgway Born 1947 Jeffersonville, IN Presently lives and works in Dallas, TX Education M.F.A., Tulane University, New Orleans, LA B.F.A., Louisville School of Art, Anchorage, KY Solo Exhibitions 2021 Nasher Public: Linda Ridgway, Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, TX From First and Last Lines, To the River Ouse: Works by Linda Ridgway, Tyler Museum of Art, Tyler, TX 2019 Cover Up, Grassland, and Shakespeare, Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, TX 2016 With or Without, Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, TX 2015 Linda Ridgway: The Sounds of Trees, part of the Cell Series at the Old Jail Art Center, Albany, TX The Alice Chronicles, Longview Museum of Fine Arts, Longview, TX 2013 The Grand Anonymous, John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, CA A Song to Herself, Stephen F. Austin State University, Cole Art Center, Nacogdoches, TX 2012 Alice, the poet and the grasslands, Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, TX Winter White: Prints by Linda Ridgway, Flatbed Press, Austin, TX 2009 A Boy’s Will, Dunn and Brown Contemporary, Dallas, TX 2007 Between, John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, California 2006 Line By Line, Dunn and Brown Contemporary, Dallas, TX 2005 Reconsider, El Paso Museum of Art, El Paso, TX while, Charles Cowles Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Consider, Dunn and Brown Contemporary, Dallas, TX 2002 Arrangements, John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2001 Without Ceremony, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA Linda Ridgway: White Flowers, Dallas Visual Art Center, TX, solo exhibition to recognize the 2001 Legend Award Artist 2000 Natural Juices: Etchings -

Teen Programs in Twenty-First Century Art Museums

TEEN PROGRAMS IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY ART MUSEUMS: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF NINE AMERICAN PROGRAMS by Rebecca Becker Daniels APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Dr. Richard Brettell, Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Frank Dufour ___________________________________________ Ms. Bonnie Pitman ___________________________________________ Dr. Nils Roemer Copyright 2016 Rebecca Becker Daniels All Rights Reserved For Tom Jungerberg Your presence made this world a better place. TEEN PROGRAMS IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY ART MUSEUMS: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF NINE AMERICAN PROGRAMS by REBECCA BECKER DANIELS, BS, MED DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS December 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to first thank the members of my committee for their patience and advice. My chair, Dr. Richard Brettell, has been my mentor and guide from my first days at The University of Texas at Dallas. I am forever grateful for all the times he dusted me off and put me back on the path. Ms. Bonnie Pitman shared her rich insight in the field of museum education over endless cups of tea, attending to practical and aesthetic details with astute reflection. Dr. Nils Roemer opened the door to the field of urban studies and guided me through the minutia of shaping a dissertation. Dr. Frank Dufour introduced me to the potential of technology in an art museum while supporting me through the IRB process. At a critical moment, a grant from Edith O’Donnell sponsored my work and a fellowship from the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History allowed me the opportunity to bring this dissertation to fruition. -

DMA Annual Report Comp1.Qx

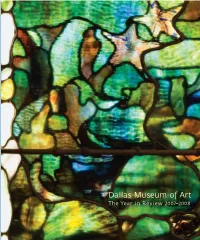

2007–2008 Dallas Museum of Art in Review The Year D ALLAS MUSEUM OF ART 2007–2008 THE YEAR IN REVIEW Dallas Museum of Art On the cover: LOUIS COMFORT TIFFANY, DESIGNER; TIFFANY GLASS AND DECORATING COMPANY, NEW YORK, NEW YORK, MANUFACTURER Window with Starfish (“Spring”) and Window with Sea Anemone (“Summer”) c. 1885–1895, glass, lead, iron, and wooden frame (original), The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., 2008.21.1–2.McD © 2009 Dallas Museum of Art President’s Report . .2 Editors: Bonnie Pitman, Queta Moore Watson, Tamara Wootton-Bonner Director’s Report . .4 Contributors: John R. Eagle, Bonnie Pitman, Tamara Wootton-Bonner, Gail Davitt, Jacqueline Allen, Tracy Bays-Boothe, Carolyn Bess, Susan Diachisin, María Teresa García Pedroche, John Easley, Linda Lipscomb, Pamela Autrey, Marci Driggers Caslin, Eric Zeidler, Carol Griffin, Center for Creative Connections . .8 Elaine Higgins, Yemi Dubale, Liza Skaggs, Jeff Guy, Liz Shipp Contributing Writer: Ellen Hirzy Acquisitions . .16 Copyediting: Queta Moore Watson Loans of Art . .49 Photography and Imaging Services: Giselle Castro-Brightenburg, Brad Flowers, Chad Redmon, Crystal Rosenthal, Neil Sreenan, Jeff Zilm Exhibitions . .50 Pages 66, 67, 76: Photos courtesy Dana Driensky Education . .56 Design: Dittmar Design, Inc./www.dittmardesign.com Printing: Grover Printing, Houston, Texas Development . .64 The Dallas Museum of Art is supported in part by the generosity of Museum members and donors and by the citizens of Dallas through the City of Dallas/Office of Cultural Affairs and the Texas Board of Trustees, Volunteers, and Staff . .80 Commission on the Arts. Audited Financial Information . .88 Additional Financial Information . .102 1717 North Harwood Dallas, Texas 75201 214 922 1200 DallasMuseumofArt.org DALLAS MUSEUM OF ART MISSION STATEMENT We collect, preserve, present, and interpret works of art of the highest quality from diverse cultures and many centuries, including that of our own time. -

Degas, Dance, Dallas Richard Kendall

Degas, Dance, Dallas Richard Kendall October 22, 2009 Dallas Museum of Art Horchow Auditorium Heather MacDonald: I am so pleased to welcome you here this evening for this lecture by Richard Kendall. It’s the first event in our 2009-2010 season of our Richard R. Brettell Lecture Series. The Brettell Lecture Series was founded in 1993 to provide a regular public venue with the DMA for the presentation of the most important and innovative new scholarship on the history of 19th and 20th century European art. This series was created with a generous endowment from museum trustees, Carolyn and Roger Horchow in honor of Dr. Richard Brettell, former Director of the Dallas Museum of Art, the current Margaret McDermott Distinguished Chair of Art and Aesthetic Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas, and himself a well-respected specialist in the art of this period. We are very pleased to have Dr. Brettell with us this evening. Over the history of the Brettell Lecture Series we have been fortunate to share with the museum’s public some of the most creative art historians working today, including Stephen Eisenman, Joachim Pissarro, and most recently Lynn Gamwell. This season will serve as yet another chapter in this proud history, as we present five major lectures, all focusing on French art of the late 19th century in our collections. If you do not already have this brochure with the details of the lectures for this season, please pick one up on your way out. It’s a two-sided brochure. We have chosen to dedicate this season of the Brettell Lectures to the late Carolyn Horchow, who passed away earlier this year. -

Envision SPRING 2005 Vol

TEXAS ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF ART ENViSiON SPRING 2005 www.tasart.org Vol. 36, No. 2 Highlights of the ■ Stay at the historic Adolphus Conference Hotel in downtown Dallas. Your conference organizers Rosemary Meza, Chair, Barbara ■ Enjoy the pre-conference Dallas 2005 Armstrong, Iris Bechtol, Randall tour of the Rachofsky House and Garrett, Omar Hernandez, Greg its contemporary art collection El Centro Metz, Luke Sides, Cathie Tyler, of painting, sculpture and and Eddy Rawlinson are excited installation, and take tours to College to offer an exciting schedule of the Meadows Museum, the activities for the 37th Annual Nasher Sculpture Garden Center, Meeting of the Texas Association the Dallas Museum of Art, and of Schools of Art. the Trammell Crow Asian ■ Conference Preview role in arts education and the Collection. March 31 – Pre-conference, investor community while also Thursday serving as a model in linking the April 1- 3 Conference, Friday insular educational programs and Saturday for artists and arts discourse with active professional artists. As The theme for the 2005 TASA educators we all strive to bring conference will be ART SPAN: relevant connective interests to bringing together the past and art history, art appreciation and future in arts and education. studio classes. Educators work to The title of this year’s conference maintain a forward-thinking refers to our keynote speaker’s balance between technology and ability to successfully pair traditional foundation skills in education with the contempo- studio classes as well as familiar- rary arts community. Richard izing students with post- Brettell is a role model for institutional support structures Two of the professors due to his interven- and resources. -

The Trammell and Margaret Crow Collection of Asian Art, Together with $23 Million in Support Funding, Is Donated to the University of Texas at Dallas

The Trammell and Margaret Crow Collection of Asian art, together with $23 Million in Support Funding, is donated to The University of Texas at Dallas A second Crow Museum on the university’s campus will allow display of a majority of the collection DALLAS, TX (Jan. 24, 2019) – The Trammell and Margaret Crow family has donated the entire collection of the Trammell and Margaret Crow Museum of Asian Art, together with $23 million of support funding, to The University of Texas at Dallas (UT Dallas) to create the Trammell and Margaret Crow Museum of Asian Art of The University of Texas at Dallas. The university will continue to operate the Trammell and Margaret Crow Museum of Asian Art in its current space in the downtown Dallas Arts District, where it has been located for more than 20 years. The gift funding will provide for the design and construction of a second museum on the UT Dallas campus in Richardson, TX, which will allow for a wider range of the full collection to be viewed by the public. The Crow Museum’s growing permanent collection demonstrates the diversity of Asian art, with more than 1,000 works from Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Thailand, Tibet, and Vietnam, spanning from the ancient to the contemporary. The collection also includes a library of over 12,000 books, catalogs, and journals. The collection was started by Dallas residents Trammell and Margaret Crow in the 1960s. Trammell Crow was legendary in the business world, known as one of the most innovative real estate developers in the United States.