Reading Environmental Relations in Contemporary Indian Fiction In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

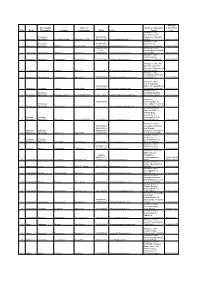

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Contemporary Literary and Cultural Studies, Vol

Contemporary Literary and Cultural Studies, Vol. I, No 1, Autumn and Winter, 2018-2019 Archive of SID Fazel Asadi Amjad,1 Professor, Department of English Language and Literature, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran. Peyman Amanolahi Baharvand,2 (Corresponding Author) PhD Candidate of English Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, North Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran. Article ID CLCS-1807-1008 Article Info Received Date: 2 November 2018 Reviewed Date: 7 January 2019 Accepted Date: 26 February 2019 Suggested Citation Asadi Amjad, F. and Amanolahi Baharvand, P. “Detrimental Impacts of Poppy Monoculture on Indigenous Subjects, Plants and Animals: An Ecocritical Reading of Amitav Ghosh's Sea of Poppies.” Contemporary Literary and Cultural Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2019, pp. 21-37. 1 [email protected] 2 [email protected] www.SID.ir 21 | Archive of SID Detrimental Impacts of Poppy Monoculture on Indigenous Subjects, Plants and Animals Abstract Critically reading Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies, the present paper attempts to explore the impacts of colonization on indigenous subjects, plants and animals. To trace the detrimental effects of colonialism on both environment and people in Sea of Poppies, this study foregrounds the reflection of the obligatory cultivation of poppy under the rule of British colonizers in India. Sea of Poppies is indeed a portrayal of the catastrophic policies enforced in India by British colonizers in the nineteenth century. In his seminal novel Ghosh deals with the changes brought about by the lucrative cultivation of poppy in the exacerbation of the financial status of indigenous subjects. Environmental devastation and the changes in the normal behavior of animals are also dealt with. -

Simple Or Complex? Learning to Predict Readability of Bengali Texts

Simple or Complex? Learning to Predict Readability of Bengali Texts Susmoy Chakraborty1*, Mir Tafseer Nayeem1*, Wasi Uddin Ahmad2 1Ahsanullah University of Science and Technology, 2University of California, Los Angeles [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Scores Readers Grade Levels 90 - 100 5th Grade Determining the readability of a text is the first step to its sim- plification. In this paper, we present a readability analysis tool 80 - 90 6th Grade capable of analyzing text written in the Bengali language to provide in-depth information on its readability and complexity. Despite being the 7th most spoken language in the world with 70 - 80 7th Grade 230 million native speakers, Bengali suffers from a lack of Readability th th fundamental resources for natural language processing. Read- Formulas 60 - 70 8 to 9 Grade ability related research of the Bengali language so far can be considered to be narrow and sometimes faulty due to the lack Input Document 50 - 60 10th to 12th Grade of resources. Therefore, we correctly adopt document-level readability formulas traditionally used for U.S. based educa- 30 - 50 College tion system to the Bengali language with a proper age-to-age comparison. Due to the unavailability of large-scale human- annotated corpora, we further divide the document-level task 0 - 30 College Graduate into sentence-level and experiment with neural architectures, which will serve as a baseline for the future works of Ben- gali readability prediction. During the process, we present Figure 1: Readability prediction task. several human-annotated corpora and dictionaries such as a document-level dataset comprising 618 documents with 12 different grade levels, a large-scale sentence-level dataset com- tools such as Grammarly2 and Readable.3 This measurement prising more than 96K sentences with simple and complex plays a significant role in many places, such as education, labels, a consonant conjunct count algorithm and a corpus of health care, and government (Grigonyte et al. -

PART 1 of Volume 13:6 June 2013

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 13:6 June 2013 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Contents Drama in Indian Writing in English - Tradition and Modernity ... 1-101 Dr. (Mrs.) N. Velmani Reflection of the Struggle for a Just Society in Selected Poems of Niyi Osundare and Mildred Kiconco Barya ... Febisola Olowolayemo Bright, M.A. 102-119 Identity Crisis in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake ... Anita Sharma, M.Phil., NET, Ph.D. Research Scholar 120-125 A Textual Study of Context of Personal Pronouns and Adverbs in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” ... Fadi Butrus K Habash, M.A. 126-146 Crude Oil Price Behavior and Its Impact on Macroeconomic Variable: A Case of Inflation ... M. Anandan, S. Ramaswamy and S. Sridhar 147-161 Using Exact Formant Structure of Persian Vowels as a Cue for Forensic Speaker Recognition ... Mojtaba Namvar Fargi, Shahla Sharifi, Mohammad Reza Pahlavan-Nezhad, Azam Estaji, and Mehi Meshkat Aldini Ferdowsi University of Mashhad 162-181 Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 13:6 June 2013 Contents List i Simplification of CC Sequence of Loan Words in Sylheti Bangla ... Arpita Goswami, Ph.D. Research Scholar 182-191 Impact of Class on Life A Marxist Study of Thomas Hardy’s Novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles .. -

Sl.No. Block Panchayath/ Municipality Location Name of Entrepreneur Mobile E-Mail Address of Akshaya Centre Akshaya Centre Phone

Akshaya Panchayath/ Name of Address of Akshaya Centre Phone Sl.No. Block Municipality Location Entrepreneur Mobile E-mail Centre No Akshaya e centre, Chennadu Kavala, Erattupetta 9961985088, Erattupetta, Kottayam- 1 Erattupetta Municipality Chennadu Kavala Sajida Beevi. T.M 9447507691, [email protected] 686121 04822-275088 Akshaya e centre, Erattupetta 9446923406, Nadackal P O, 2 Erattupetta Municipality Hutha Jn. Shaheer PM 9847683049 [email protected] Erattupetta, Kottayam 04822-329714 9645104141 Akshaya E-Centre, Binu- Panackapplam,Plassnal 3 Erattupetta Thalappalam Pllasanal Beena C S 9605793000 [email protected] P O- 686579 04822-273323 Akshaya e-centre, Medical College, 4 Ettumanoor Arpookkara Panampalam Renjinimol P S 9961777515 [email protected] Arpookkara, Kottayam 0481-2594065 Akshaya e centre, Hill view Bldg.,Oppt. M G. University, Athirampuzha 5 Ettumanoor Athirampuzha Amalagiri Shibu K.V. 9446303157 [email protected] Kottayam-686562 0481-2730349 Akshaya e-centre, , Thavalkkuzhy,Ettumano 6 Ettumanoor Athirampuzha Thavalakuzhy Josemon T J 9947107199 [email protected] or P.O-686631 0418-2536494 Akshaya e-centre, Near Cherpumkal 9539086448 Bridge, Cherpumkal P O, 7 Ettumanoor Aymanam Valliyad Nisha Sham 9544670426 [email protected] Kumarakom, Kottayam 0481-2523340 Akshaya Centre, Ettumanoor Municipality Building, 8 Ettumanoor Muncipality Ettumanoor Town Reeba Maria Thomas 9447779242 [email protected] Ettumanoor-686631 0481-2535262 Akshaya e- 9605025039 Centre,Munduvelil Ettumanoor -

Toxic Consciousness in Indra Sinha's Animal's People

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 18:5 May 2018 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== Toxic Consciousness in Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People: An Ecocritical Study T. Geetha, Ph.D. Scholar & Dr. K. Maheshwari Abstract Literary writers, now-a-days, have penned down the destruction of nature and environment in all the genres of literature. The main objectives of the ecocritical writers are to provide awareness towards the end of peaceful nature. They particularly point out the polluted environment that leads to the execution of living beings in future. Indra Sinha is such the ecocritical writer who highlights the Bhopal gas tragedy and inhumanities of corporate companies, in his novel, Animal’s People. The environmental injustice that took place in the novel, clearly resembles the Bhopal Gas Tragedy that happened in 1984. The present study exhibits the consciousness of the toxic gas and its consequences to the innocent people in the novel. Keywords: Ecocriticism, Toxic Consciousness, Environmental Injustice, Bhopal gas tragedy and Corporate Inhumanities. Indra Sinha ==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:5 May 2018 T. Geetha, Ph.D. Scholar & Dr. K. Maheshwari Toxic Consciousness in Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People: An Ecocritical Study 110 Indra Sinha, born in 1950, is the writer of English and Indian descent. His novel Animal People was published in 2009 that commemorated 25 years of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy. It recalled the world’s worst industrial disaster that took place in Indian city of Bhopal. On a December night in 1984, the ‘Union Carbide India Limited’ (UCIL), the part of US based multinational company, pesticide plant in Bhopal leaked around 27 tons of poisonous Methyl isocyanate gas, instantly killed thousands of people. -

2 Apar Gupta New Style Complete.P65

INDIAN LAWYERS IN POPULAR HINDI CINEMA 1 TAREEK PAR TAREEK: INDIAN LAWYERS IN POPULAR HINDI CINEMA APAR GUPTA* Few would quarrel with the influence and significance of popular culture on society. However culture is vaporous, hard to capture, harder to gauge. Besides pure democracy, the arts remain one of the most effective and accepted forms of societal indicia. A song, dance or a painting may provide tremendous information on the cultural mores and practices of a society. Hence, in an agrarian community, a song may be a mundane hymn recital, the celebration of a harvest or the mourning of lost lives in a drought. Similarly placed as songs and dance, popular movies serve functions beyond mere satisfaction. A movie can reaffirm old truths and crystallize new beliefs. Hence we do not find it awkward when a movie depicts a crooked politician accepting a bribe or a television anchor disdainfully chasing TRP’s. This happens because we already hold politicians in disrepute, and have recently witnessed sensationalistic news stories which belong in a Terry Prachet book rather than on prime time news. With its power and influence Hindi cinema has often dramatized courtrooms, judges and lawyers. This article argues that these dramatic representations define to some extent an Indian lawyer’s perception in society. To identify the characteristics and the cornerstones of the archetype this article examines popular Bollywood movies which have lawyers as its lead protagonists. The article also seeks solutions to the lowering public confidence in the legal profession keeping in mind the problem of free speech and censorship. -

An Ecological Human Bond with Nature in Indra Sinha's Animal's

International Journal of Engineering Trends and Applications (IJETA) – Volume 2 Issue 3, May-Jun 2015 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS An Ecological Human Bond With Nature In Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People Ms. D.Aswini [1], Dr.S. Thirunavukkarasu [2] Research Scholar [1], Assistant Professor [2] MuthurangamGovt Arts College Otteri, Vellore Tamil Nadu - India ABSTRACT This paper explores the thematic desire to establish an ecological human bond with nature inIndraSinha’sAnimal’s People. Nature and literature have always shared a close relationship. India is a country with variety of ecosystems which ranges from Himalayas in the North to plateaus of South and from the dynamic Sunderbans in the East to dry Thar of the West. However our ecosystems have been affected due to increase in population and avarice of mankind in conquering more lands. As Environment and Literature are entwined, it is the duty of everyone to protect nature through words. Ecocriticism takes an earth centered approach to literary criticism. Although there are not many, there are few novels that can be read through the lens of ecocriticism. Keywords:- Chozhan, gurukulas I. INTRODUCTION literature and epics. Nature has been intimately In the same way,IndraSinha has riveted in connected with life in Indian tradition. Mountains, unveiling the concept of ecology in his novel. In particularly Himalayas are said to be the abode of God. Animal’s People, IndraSinha brings to limelight, the Rivers are considered and worshipped as goddesses, corporate crime of Bhopal gas attack in 1984. He has especially the holiest of holy rivers Ganga is a source done a rigorous research in their specific area of of salvation for anyone. -

POSTMODERN TRAITS in the NOVELS of AMITAV GHOSH Prof

www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 POSTMODERN TRAITS IN THE NOVELS OF AMITAV GHOSH Prof. R. Chenniappan R. Saravana Suresh Research scholar Research scholar Paavai Engineering college Paavai Engineering college Pachal, Namakkal. Pachal, Namakkal. Indian writing in English has stamped its greatness by mixing up tradition and modernity in the production of art. At the outset, the oral transmission of Indian literary works gained ground gradually. It created an indelible mark in the mind and heart of the lovers of art. The interest in literature lit the burning thirst of the writers which turned their energy and technique to innovate new form and style of writing. Earlier novels projected India’s heritage, tradition, cultural past and moral values. But a remarkable change can be noticed in the novels published after the First World War, which is called, modernism. The novels written in the late 20th century, especially after the Second World War, are considered postmodern novels. Salman Rushdie, Vikaram Seth, Shashi Tharoor, Upamanyu Chatterjee and Amitav Ghosh are the makers of new pattern in writing novels with post-modern thoughts and emotions. Amitav Ghosh is one among the postmodernists. He is immensely influenced by the political and cultural milieu of post independent India. Being a social anthropologist and having the opportunity of visiting alien lands, he comments on the present scenario the world is passing through in his novels. Cultural fragmentation, colonial and neo-colonial power structures, cultural degeneration, the materialistic offshoots of modern civilization, dying of human relationships,blending of facts and fantasy, search for love and security, diasporas, etc… are the major preoccupations in the writings of Amitav Ghosh. -

Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons a Thesis

Disablement, Diversity, Deviation: Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Sarah Gibbons 2016 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation brings disability studies and postcolonial studies into dialogue with discourse surrounding risk in the environmental humanities. The central question that it investigates is how critics can reframe and reinterpret existing threat registers to accept and celebrate disability and embodied difference without passively accepting the social policies that produce disabling conditions. It examines the literary and rhetorical strategies of contemporary cultural works that one, promote a disability politics that aims for greater recognition of how our environmental surroundings affect human health and ability, but also two, put forward a disability politics that objects to devaluing disabled bodies by stigmatizing them as unnatural. Some of the major works under discussion in this dissertation include Marie Clements’s Burning Vision (2003), Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People (2007), Gerardine Wurzburg’s Wretches & Jabberers (2010) and Corinne Duyvis’s On the Edge of Gone (2016). The first section of this dissertation focuses on disability, illness, industry, and environmental health to consider how critics can discuss disability and environmental health in conjunction without returning to a medical model in which the term ‘disability’ often designates how closely bodies visibly conform or deviate from definitions of the normal body. -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

Toxic Lunch in Bhopal and Chemical Publics

Article Science, Technology, & Human Values 2016, Vol. 41(5) 849-875 ª The Author(s) 2016 Toxic Lunch in Bhopal Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0162243916645196 and Chemical Publics sthv.sagepub.com Rahul Mukherjee1 Abstract On November 28, 2009, as part of events marking the twenty-fifth anni- versary of the disaster at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, gas survivors protested the contents of the report prepared by government scientists that mocked their complaints about contamination. The survivors shifted from the scientific document to a mediated lunch invitation performance, purporting to serve the same chemicals as food that the report had categorized as having no toxic effects. I argue that the lunch spread, consisting of soil and water from the pesticide plant, explicitly front-staged and highlighted the survivor’s forced intimate relationship with such chemicals, in order to reshape public perception of risks from toxins. Chemical matter like sevin tar and naphthol tar bound politicians, scien- tists, corporations, affected communities, and activists together, as these stakeholders debated the potential effects of toxic substances. This gave rise to an issue-based ‘‘chemical public.’’ Borrowing from such theoretical concepts as ‘‘ontologically heterogeneous publics’’ and ‘‘agential realism,’’ I track the existing and emerging publics related to the disaster and the campaigns led by the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal advocacy group. 1University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia,