American Sexual Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is a Rebound Relationship?

What Is A Rebound Relationship? By Nina Atwood What is the definition of a "rebound relationship"? Is it true they can be unhealthy? - David Rebound relationships occur very shortly after the Commitment hunger. "My last boyfriend dated end of a significant love, and sometimes begin me for three years without making a commitment, before the end. The problem with a rebound is that so I'm expecting an engagement ring within six it doesn't allow time for the grieving and healing months or I'm out of here." process to be complete. Chronic fear and anxiety. "After what my ex did When this happens, there is emotional confusion. to me, I have to constantly check to see that you're Sometimes, the feelings for the old partner simply really there for me, even if that drives you crazy." transfer to the new one, and that results in the illusion that you've found someone totally Skyrocket relationship. Rebound dating "different," when, in fact, you've found someone relationships are often too fast-paced, with a false very much like your old love. Often the issues that sense of urgency, in order to "make sure" that this drove you away from your previous partner are the one sticks. very ones with which you eventually find yourself grappling in the new relationship. The biggest risk of a rebound is that it serves its purpose and then the re-bounder moves on, Rebound relationships serve a purpose: To protect leaving someone else devastated. If you're dating the heart from the devastation of losing someone someone who has just left another relationship, very important. -

Asexuality: a Mixed-Methods Approach

Arch Sex Behav (2010) 39:599–618 DOI 10.1007/s10508-008-9434-x ORIGINAL PAPER Asexuality: A Mixed-Methods Approach Lori A. Brotto Æ Gail Knudson Æ Jess Inskip Æ Katherine Rhodes Æ Yvonne Erskine Received: 13 November 2007 / Revised: 20 June 2008 / Accepted: 9 August 2008 / Published online: 11 December 2008 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract Current definitions of asexuality focus on sexual having to ‘‘negotiate’’ sexual activity. There were not higher attraction, sexual behavior, and lack of sexual orientation or rates of psychopathology among asexuals; however, a subset sexual excitation; however, the extent to which these defi- might fit the criteria for Schizoid Personality Disorder. There nitions are accepted by self-identified asexuals is unknown. was also strong opposition to viewing asexuality as an ex- The goal of Study 1 was to examine relationship character- treme case of sexual desire disorder. Finally, asexuals were istics, frequency of sexual behaviors, sexual difficulties and very motivated to liaise with sex researchers to further the distress, psychopathology, interpersonal functioning, and scientific study of asexuality. alexithymia in 187 asexuals recruited from the Asexuality Visibility and Education Network (AVEN). Asexual men Keywords Asexuality Á Sexual identity Á Sexual (n = 54) and women (n = 133) completed validated ques- orientation Á Sexual attraction Á Romantic attraction Á tionnaires online. Sexual response was lower than normative Qualitative methodology data and was not experienced as distressing, and masturba- tion frequency in males was similar to available data for sexual men. Social withdrawal was the most elevated per- Introduction sonality subscale; however, interpersonal functioning was in the normal range. -

Topics in Human Sexuality: Sexuality Across the Lifespan Adulthood/Male and Female Sexuality

Most people print off a copy of the post test and circle the answers as they read through the materials. Then, you can log in, go to "My Account" and under "Courses I Need to Take" click on the blue "Enter Answers" button. After completing the post test, you can print your certificate. Topics in Human Sexuality: Sexuality Across the Lifespan Adulthood/Male and Female Sexuality Introduction The development of sexuality is a lifelong process that begins in infancy. As we move from infancy to adolescence and adolescence to adulthood, there are many sexual milestones. While adolescent sexuality is a time in which sexual maturation, interest and experience surge, adult sexuality continues to be a time of sexual unfolding. It is during this time that people consolidate their sexual orientation and enter into their first mature, and often long term, sexual relationships. This movement towards mature sexuality also has a number of gender-specific issues as males and females often experience sexuality differently. As people age, these differences are often marked. In addition to young and middle age adults, the elderly are often an overlooked group when it comes to discussion of sexuality. Sexuality, however, continues well into what are often considered the golden years. This course will review the development of sexuality using a lifespan perspective. It will focus on sexuality in adulthood and in the elderly. It will discuss physical and psychological milestones connected with adult sexuality. Educational Objectives 1. Discuss the process of attaining sexual maturity, including milestones 2. Compare and contrast remaining singles, getting married and cohabitating 3. -

First Evidence of Multiple Paternity in the Bull Shark (Carcharhinus Leucas) Agathe Pirog, Sébastien Jaquemet, Marc Soria, Hélène Magalon

First evidence of multiple paternity in the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) Agathe Pirog, Sébastien Jaquemet, Marc Soria, Hélène Magalon To cite this version: Agathe Pirog, Sébastien Jaquemet, Marc Soria, Hélène Magalon. First evidence of multiple paternity in the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas). Marine and Freshwater Research, CSIRO Publishing, 2015, 10.1071/mf15255. hal-01253775 HAL Id: hal-01253775 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01253775 Submitted on 4 May 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. First evidence of multiple paternity in the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) Agathe PirogA, Se´bastien JaquemetA,B, Marc SoriaC and He´le`ne MagalonA,B,D AUniversite´ de La Re´union, UMR 9220 ENTROPIE (Universite´ de La Re´union/IRD/CNRS), 15 Avenue Rene´ Cassin, CS 92003, F-97744 Saint Denis Cedex 09, La Re´union, France. BLaboratory of Excellence CORAIL, 58, Avenue Paul Alduy, F-66860 Perpignan Cedex, France. CIRD Re´union, UMR 248 MARBEC, CS 41095 2 rue Joseph Wetzell, F-97492 Sainte-Clotilde, La Re´union, France. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The present study assessed the occurrence of multiple paternity in four litters of bull shark Carcharhinus leucas (n ¼ 5, 8, 9 and 11 embryos) sampled at Reunion Island in the Western Indian Ocean. -

A Personal Construct Psychology Perspective on Sexual Identity

A personal construct psychology perspective on sexual identity Item Type Thesis Authors Morano, Laurie Ann Download date 24/09/2021 18:24:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/718 A PERSONAL CONSTRUCT PSYCHOLOGY PERSPECTIVE ON SEXUAL IDENTITY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY OF THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT NEW PALTZ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MENTAL HEALTH COUNSELING By Laurie Ann Morano November 2007 Notice: Signature Page Not Included This thesis has been signed and approved by the appropriate parties. The signature page has been removed from this digital version for privacy reasons. The signature page is maintained as part of the official version of the thesis in print that is kept in Special Collections of Sojourner Truth Library at SUNY New Paltz. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Jonathan Raskin for his patience and unwavering support during this process. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to my love, Kristina. You knew just when to push me to work and just when to keep quiet when I should have been working, but was not – it was a fine line, but you walked it perfectly. Thank you to all my friends and family that believed I would finish this one day. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Acknowledgements……………………………………………….iii II. Abstract……………………………………………………………vi III. Introduction………………………………………………………...1 A Personal Construct Psychology Perspective on Sexual Identity ………………………………………………………………….1 IV. Homosexual Identity Development Models……………………….4 Plummer’s Interactionist Account of Male Homosexuality…...7 Ponse’s Theory of Lesbian Identity Development……………..9 Cass’s Theory of Homosexual Identity Formation…………….11 Troiden’s Ideal-Typical Model of Homosexual Identity Formation ………………………………………………………………….14 V. -

Phenomenological Claim of First Sexual Intercourse Among Individuals of Varied Levels of Sexual Self-Disclosure

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2005 Phenomenological claim of first sexual intercourse among individuals of varied levels of sexual self-disclosure Lindsey Takara Doe The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Doe, Lindsey Takara, "Phenomenological claim of first sexual intercourse among individuals of varied levels of sexual self-disclosure" (2005). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5441. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5441 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature Yes, I grant permission ___ No, I do not grant permission ___ Author's Signature: Date: ^ h / o 5 __________________ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's -

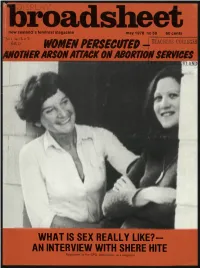

AN INTERVIEW with SHERE HITE Registered at the GPO, Wellington, As a Magazine Fronting Up

D iS P i A Y new Zealand’s feminist magazine may 1978 no 59 60 cents | -3<M q-iXoS 0& D WOMEN PERSECUTED 4 TUCiCRS CCI1EGES MOTHER ARSON ATTACK ON ABORTION SERVICES «LAND WHAT IS SEX REALLY LIKE?— AN INTERVIEW WITH SHERE HITE Registered at the GPO, Wellington, as a magazine Fronting up Office Wanted if you could send us the extra money. You don’t have to, but it would help Office hours for Broadsheet are: More advertisements for Broadsheet. a lot! Mon — Thurs: 9 a.m. — 3 p.m. Readers are beginning to make more Friday: 9 a.m. — 12 noon. use of our very reasonable Classified Now you see it, now you It is best to ring first before visiting as Advertisements service (roughly 5 cents don’t we are sometimes out and about. per word) and we hear that most of There are sometimes people here our advertisers get a good response. So Or — The Great Disappearing Trick. after 3 p.m. too. if you need a flat, a flatmate, a Job, “Ladies and ladies . .” (InterJection: a workmate, a travelling companion — “Women!”) “ . in my right hand I Phone: 378-954. or if you’ve got something to sell — have a book marked Broadsheet. Address: 65 Victoria St. West, City remember that Broadsheet is a good Abracadabra, hocus pocus, — now (Just above Albert St.). place to advertise. Please let our where is it?” Mystified silence. Non advertisers know that you saw their comprehension on the part of the Broadsheet Benefit ad. in Broadsheet, and if you can Collective — where do our precious persuade any (non-sexist) businesses to magazines and books get to? We have A multi-media women’s show has been advertise with us we’d be delighted. -

The Effects of Sex Guilt and Communication on Condom Use" (1997)

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1997 The ffecE ts of Sex Guilt and Communication on Condom Use Renée M. Souva Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Psychology at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Souva, Renée M., "The Effects of Sex Guilt and Communication on Condom Use" (1997). Masters Theses. 1847. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1847 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. 1 Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author Date The Effects of Sex Guilt and Communication on Condom Use (TITLE) BY Renee M. Souva THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1997 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING Condom Use 2 Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine whether sex guilt and communication were related to condom use. -

Sexual Behavior and Satisfaction in Same-Sex and Different-Sex Relationships

Sexual Behavior and Satisfaction in Same-Sex and Different-Sex Relationships Taylor Orth Department of Sociology, Stanford University Author Contact Information: 450 Serra Mall Building 120, Room 30D Stanford, CA 94305 [email protected] (281) 772-0155 1 Sexual Behavior and Satisfaction in Same-Sex and Different-Sex Relationships Abstract: Among both academics and the lay public remains a widespread and taken- for-granted belief that male and female sexuality are fundamentally different and that men and women in sexual relationships compromise on such differences. More recently, however, social scientists have begun to question the extent to which gender gaps in sexual desire may be socially rather than biologically determined. Because collecting accurate and representative data on sexual behavior within relationships is often challenging, very little empirical evidence has been available to scientifically disentangle these competing perspectives. This study evaluates variation in the sexual behavior and satisfaction of same-sex and different-sex couples through an analysis of two nationally representative American surveys, How Couples Meet and Stay Together (HCMST) and The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Findings demonstrate that women in same-sex relationships have sex less often than other couple pairings. Men in same-sex relationships report significantly lower sexual satisfaction and higher rates of non-monogamy relative to other couples, even after controlling for relevant factors. Overall, the results from this study support the notion that sexual relationships function differently in the absence of a male or female partner, but present a less deterministic and more socially complex perspective than has traditionally been accepted. -

Why Humans Have Sex

Arch Sex Behav (2007) 36:477–507 DOI 10.1007/s10508-007-9175-2 ORIGINAL PAPER Why Humans Have Sex Cindy M. Meston Æ David M. Buss Received: 20 December 2005 / Revised: 18 July 2006 / Accepted: 24 September 2006 / Published online: 3 July 2007 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract Historically, the reasons people have sex have Keywords Sexual motivation Á Sexual intercourse Á been assumed to be few in number and simple in nature–to Gender differences reproduce, to experience pleasure, or to relieve sexual tension. Several theoretical perspectives suggest that mo- tives for engaging in sexual intercourse may be larger in Introduction number and psychologically complex in nature. Study 1 used a nomination procedure that identified 237 expressed Why people have sex is an extremely important, but reasons for having sex, ranging from the mundane (e.g., ‘‘I surprisingly little studied topic. One reason for its relative wanted to experience physical pleasure’’) to the spiritual neglect is that scientists might simply assume that the (e.g., ‘‘I wanted to get closer to God’’), from altruistic (e.g., answers are obvious: to experience sexual pleasure, to ‘‘I wanted the person to feel good about himself/herself’’) relieve sexual tension, or to reproduce. Previous research to vengeful (e.g., ‘‘I wanted to get back at my partner for already tells us that the answers cannot be as few or having cheated on me’’). Study 2 asked participants psychologically simple. Leigh (1989), for example, docu- (N = 1,549) to evaluate the degree to which each of the 237 mented seven reasons for sex: pure pleasure, to express reasons had led them to have sexual intercourse. -

Degrees of Freedom

February 2015 D of F EXPANDING COLLEGE OPPORTUNITIES for Currently and Formerly Incarcerated Californians Stanford Criminal Justice Center Chief Justice Earl Warren Stanford Law School Institute on Law and Social Policy UC Berkeley School of Law DEGREES OF FREEDOM: Expanding College Opportunities for Currently and Formerly Incarcerated Californians February 2015 A report of the Renewing Communities Initiative Acknowledgements This report was co-written by Debbie Mukamal, Rebecca Silbert, and Rebecca M. Taylor. This report is part of a larger initiative – Renewing Communities – to expand college opportunities for currently and formerly incarcerated students in California. Nicole Lindahl was a contributing author; Nicole Lindahl and Laura Van Tassel also provided research assistance for this report. The research and publication of this report has been supported by the Ford Foundation. The authors thank Douglas Wood of the Ford Foundation for his vision and leadership which catapulted this report. The authors are grateful to the many people who provided information, experience, and guidance in the development of this report. These individuals are listed in Appendix A. Any errors or misstatements in this report are the responsibility of the authors; the recommendations made herein may, or may not, be supported by the individuals listed in Appendix A. Founded in 2005, the Stanford Criminal Justice Center serves as a research and policy institute on issues related to the criminal justice system. Its efforts are geared towards both generating policy research for the public sector, as well as providing pedagogical opportunities to Stanford Law School students with academic or career interests in criminal law and crime policy. -

Description of Grounds

Grounds of Marriage Nullity The following are the possible grounds that can be used in a marriage case before a Tribunal. There is a brief description and a list of questions relating to each ground. The judges decide each case solely on the basis of whether the grounds are proven by the testimony submitted by the parties, their witnesses, and expert consultants. If you are starting a marriage case with the Tribunal, the Case Assessor will help you to suggest or propose grounds for your case. If you have already started a case, or if you are a Respondent in a case, your Advocate can help you to understand the grounds. If you believe that one or more grounds may be applicable to your case, the questions will help you in selecting possible witnesses. Witnesses will be asked questions related to the ground or grounds used in the case. Every marriage case must have at least one ground. At the beginning of the process, the parties suggest possible grounds and explain in written statements why they believe those grounds apply to their case. After both parties have had the opportunity to do this, the Judges will set the actual ground or grounds for the case. The parties will be notified of the grounds. They may express their objections to the chosen grounds if they so choose, and the Judges may then reconsider. The Judges may select several grounds at the beginning of the case; the testimony of the parties and witnesses will determine which is the best ground on which to judge the case in the end.