Big Island Feral Cat Eradication Campaigns: an Overview and Status Update of Two Signifi Cant Examples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Christmas Island. the Presence of Trypanosoma in Cats and Rats (From All Three Locations) and Leishmania

Invasive animals and the Island Syndrome: parasites of feral cats and black rats from Western Australia and its offshore islands Narelle Dybing BSc Conservation Biology, BSc Biomedical Science (Hons) A thesis submitted to Murdoch University to fulfil the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the discipline of Biomedical Science 2017 Author’s Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work that has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Narelle Dybing i Statement of Contribution The five experimental chapters in this thesis have been submitted and/or published as peer reviewed publications with multiple co-authors. Narelle Dybing was the first and corresponding author of these publications, and substantially involved in conceiving ideas and project design, sample collection and laboratory work, data analysis, and preparation and submission of manuscripts. All publication co-authors have consented to their work being included in this thesis and have accepted this statement of contribution. ii Abstract Introduced animals impact ecosystems due to predation, competition and disease transmission. The effect of introduced infectious disease on wildlife populations is particularly pronounced on islands where parasite populations are characterised by increased intensity, infra-community richness and prevalence (the “Island Syndrome”). This thesis studied parasite and bacterial pathogens of conservation and zoonotic importance in feral cats from two islands (Christmas Island, Dirk Hartog Island) and one mainland location (southwest Western Australia), and in black rats from Christmas Island. The general hypothesis tested was that Island Syndrome increases the risk of transmission of parasitic and bacterial diseases introduced/harboured by cats and rats to wildlife and human communities. -

Endemic Species of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean D.J

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 055–114 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(2).2019.055-114 Endemic species of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean D.J. James1, P.T. Green2, W.F. Humphreys3,4 and J.C.Z. Woinarski5 1 73 Pozieres Ave, Milperra, New South Wales 2214, Australia. 2 Department of Ecology, Environment and Evolution, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria 3083, Australia. 3 Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. 4 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, Western Australia 6009, Australia. 5 NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Charles Darwin University, Casuarina, Northern Territory 0909, Australia, Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – Many oceanic islands have high levels of endemism, but also high rates of extinction, such that island species constitute a markedly disproportionate share of the world’s extinctions. One important foundation for the conservation of biodiversity on islands is an inventory of endemic species. In the absence of a comprehensive inventory, conservation effort often defaults to a focus on the better-known and more conspicuous species (typically mammals and birds). Although this component of island biota often needs such conservation attention, such focus may mean that less conspicuous endemic species (especially invertebrates) are neglected and suffer high rates of loss. In this paper, we review the available literature and online resources to compile a list of endemic species that is as comprehensive as possible for the 137 km2 oceanic Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the north-eastern Indian Ocean. -

Proposed Management Plan for Cats and Black Rats on Christmas Island

Proposed management plan for cats and black rats on Christmas Island Dave Algar and Michael Johnston 2010294-0710 Recommended citation: Algar, D & Johnston, M. 2010. Proposed Management plan for cats and black rats of Christmas Island, Western Australian Department of Environment and Conservation. ISBN: 978-1-921703-10-2 PROPOSED MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR CATS AND BLACK RATS ON CHRISTMAS ISLAND Dave Algar1 and Michael Johnston2 1 Department of Environment and Conservation, Science Division, Wildlife Place, Woodvale, Western Australia 6946 2 Department of Sustainability and Environment, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, 123 Brown Street, Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 July 2010 Front cover Main: Feral cat at South Point, Christmas Island (Dave Algar). Top left: Feral cat approaching bait suspension device on Christmas Island (Scoutguard trail camera). Top right: Black rats in bait station on Cocos (Keeling) Islands that excludes land crabs (Neil Hamilton). ii Proposed management plan for cats and black rats on Christmas Island iii Proposed management plan for cats and black rats on Christmas Island Contents LIST OF FIGURES VI LIST OF TABLES VI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VII REPORT OUTLINE 1 1. BACKGROUND 3 1.1 Impact of invasive cats and rats on endemic island fauna 3 1.2 Impact of feral cats and rats on Christmas Island 3 1.3 Introduction of cats and rats onto Christmas Island 7 1.4 Previous studies on the management of cats and rats on Christmas Island 8 1.4.1 Feral cat abundance and distribution 8 1.4.2 Feral cat diet 8 1.4.3 Rat abundance and distribution 9 1.5 Review of current control measures on Christmas Island 9 1.5.1 Management of domestic and stray cats in settled areas 9 1.5.2 Management of feral cats 10 1.5.3 Rat management 10 1.6 Recommendations to control/eradicate cats and black rats on Christmas Island 10 2. -

Decline and Extinction of Australian Mammals Since European Settlement

Ongoing unraveling of a continental fauna: Decline FEATURE ARTICLE and extinction of Australian mammals since European settlement John C. Z. Woinarskia,b,1, Andrew A. Burbidgec, and Peter L. Harrisond aNorthern Australian Hub of National Environmental Research Program and bThreatened Species Recovery Hub of National Environmental Science Program, SEE COMMENTARY Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia; cResearch Fellow, Department of Parks and Wildlife, Wanneroo, WA 6069, Australia; and dMarine Ecology Research Centre, School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia This Feature Article is part of a series identified by the Editorial Board as reporting findings of exceptional significance. Edited by William J. Bond, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, and approved January 13, 2015 (received for review September 10, 2014) The highly distinctive and mostly endemic Australian land mam- than previously recognized and that many surviving Australian mal fauna has suffered an extraordinary rate of extinction (>10% native mammal species are in rapid decline, notwithstanding the of the 273 endemic terrestrial species) over the last ∼200 y: in generally low level in Australia of most of the threats that are comparison, only one native land mammal from continental North typically driving biodiversity decline elsewhere in the world. America became extinct since European settlement. A further 21% of Australian endemic land mammal species are now assessed to Earlier Losses be threatened, indicating that the rate of loss (of one to two European settlement at 1788 marks a particularly profound extinctions per decade) is likely to continue. Australia’s marine historical landmark for the Australian environment, the opening mammals have fared better overall, but status assessment for up of the continent to a diverse array of new factors, and an ap- them is seriously impeded by lack of information. -

Exotic-Rodents-Background.Pdf

BACKGROUND DOCUMENT for the THREAT ABATEMENT PLAN to reduce the impacts of exotic rodents on biodiversity on Australian offshore islands of less than 100 000 hectares 2009 Contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................5 2 The problem with exotic rodents .....................................................................................6 2.1 Rodent species on Australian islands ........................................................................6 2.2 Australian islands with rodents...................................................................................7 2.3 Impacts of exotic rodents on island biodiversity and economic well-being.................8 3 Management of the threat...............................................................................................11 3.1 A response framework .............................................................................................11 3.2 Setting priorities........................................................................................................11 3.3 The toolbox...............................................................................................................12 3.4 Eradication ...............................................................................................................14 3.5 Sustained control......................................................................................................14 3.6 Stopping new invasions............................................................................................15 -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Therya ISSN: 2007-3364 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste Woinarski, John C. Z.; Burbidge, Andrew A.; Harrison, Peter L. A review of the conservation status of Australian mammals Therya, vol. 6, no. 1, January-April, 2015, pp. 155-166 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste DOI: 10.12933/therya-15-237 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=402336276010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative THERYA, 2015, Vol. 6 (1): 155-166 DOI: 10.12933/therya-15-237, ISSN 2007-3364 Una revisión del estado de conservación de los mamíferos australianos A review of the conservation status of Australian mammals John C. Z. Woinarski1*, Andrew A. Burbidge2, and Peter L. Harrison3 1National Environmental Research Program North Australia and Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the National Environmental Science Programme, Charles Darwin University, NT 0909. Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (JCZW) 2Western Australian Wildlife Research Centre, Department of Parks and Wildlife, PO Box 51, Wanneroo, WA 6946, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (AAB) 3Marine Ecology Research Centre, School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (PLH) *Corresponding author Introduction: This paper provides a summary of results from a recent comprehensive review of the conservation status of all Australian land and marine mammal species and subspecies. -

Invasive Rats on Tropical Islands: Their History, Ecology, Impacts and Eradication

Invasive rats on tropical islands: Their history, ecology, impacts and eradication Karen Varnham Invasive rats on tropical islands: Their history, ecology, impacts and eradication Research Report Karen Varnham Published by the RSPB Conservation Science Department RSPB Research Report No 41 Published by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2DL, UK. © 2010 The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2DL, UK. All rights reserved. No parts of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the Society. ISBN 978-1-905601-28-8 Recommended citation: Varnham, K (2010). Invasive rats on tropical islands: Their history, ecology, impacts and eradication. RSPB Research Report No. 41. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Sandy, Bedfordshire, UK. ISBN 978-1-905601-28-8 Cover photograph: John Cancalosi (FFI) For further information, please contact: Karen Varnham Dr Richard Cuthbert School of Biological Sciences Royal Society for the Protection of Birds University of Bristol The Lodge, Sandy Woodland Road, Bristol, BS8 2UG, UK Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL, UK Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Executive summary From their original ranges in Asia, black and brown rats (R. rattus and R. norvegicus) are now present across much of the world, including many island groups. They are among the most widespread and damaging invasive mammalian species in the world, known to cause significant ecological damage to a wide range of plant and animal species. Whilst their distribution is now global, this report focuses on their occurrence, ecology and impact within the tropics and reviews key factors relating to the eradication of these species from tropical islands based on both eradication successes and failures. -

Absence of Trypanosomes in Feral Cats and Black Rats from Christmas Island and Western Australia

1 Ghosts of Christmas past?: absence of trypanosomes in feral cats and black rats from Christmas Island and Western Australia N. A. DYBING1*,C.JACOBSON1,2,P.IRWIN1,2,D.ALGAR3 and P. J. ADAMS1 1 School of Veterinary & Life Sciences, Murdoch University, Perth, Western Australia, Australia 2 Vector- and Water-Borne Pathogen Research Group, Murdoch University, Perth, Western Australia, Australia 3 Department of Parks and Wildlife, Science and Conservation, Perth, Western Australia, Australia (Received 5 November 2015; revised 5 January 2016; accepted 27 January 2016) SUMMARY Trypanosomes and Leishmania are vector-borne parasites associated with high morbidity and mortality. Trypanosoma lewisi, putatively introduced with black rats and fleas, has been implicated in the extinction of two native rodents on Christmas Island (CI) and native trypanosomes are hypothesized to have caused decline in Australian marsupial popula- tions on the mainland. This study investigated the distribution and prevalence of Trypanosoma spp. and Leishmania spp. in two introduced pests (cats and black rats) for three Australian locations. Molecular screening (PCR) on spleen tissue was performed on cats from CI (n = 35), Dirk Hartog Island (DHI; n = 23) and southwest Western Australia (swWA) (n = 58), and black rats from CI only (n = 46). Despite the continued presence of the intermediate and mechanical hosts of T. lewisi, there was no evidence of trypanosome or Leishmania infection in cats or rats from CI. Trypanosomes were not identified in cats from DHI or swWA. These findings suggest T. lewisi is no longer present on CI and endemic Trypanosoma spp. do not infect cats or rats in these locations. -

Surveys of Small and Medium Sized Mammals in Northern Queensland with Emphasis on Improving Survey Methods for Detecting Low Density Populations

Surveys of small and medium sized mammals in northern Queensland with emphasis on improving survey methods for detecting low density populations Natalie Waller Bachelor of Applied Science (Hons.) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Agriculture and Food Science ABSTRACT The primary aim of this thesis was to investigate the decline of small and medium sized mammals in northern Queensland by: determining the population status of the endangered Bramble Cay melomys, Melomys rubicola and investigate the cause of any decline; collating all historical mammal relative abundance data (mammals ≤ 5kg) for the Northern Gulf Management Region (NGMR) with comparisons with other areas in northern Australia where mammal declines have occurred. The secondary aim of the thesis was to investigate methods to improve detection of mammals in northern Queensland by critically determining if camera trapping improved the detection of mammals; and by evaluating the effectiveness of two wax block baits for attracting mammals using camera trapping. Data collection on Bramble Cay occurred during three survey periods between 2011 and 2014. Survey efforts totalled 1,170 Elliott, 60 camera trap-nights and 10 hours of active searches. To document the variation in cay size and vegetation extent, during each survey, we measured the island area above high tide and vegetated area using GPS. Mammal relative abundance data were collated for the NG region with a total of 276 1-ha plots surveyed between 2003 and 2016. Of these, 149 plots were surveyed once, 100 plots twice and 27 plots three times. -

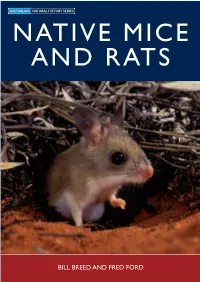

NATIVE MICE and RATS BILL BREED and FRED FORD NATIVE MICE and RATS Photos Courtesy Jiri Lochman,Transparencies Lochman

AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES NATIVE MICE AND RATS BILL BREED AND FRED FORD BILL BREED AND RATS MICE NATIVE NATIVE MICE AND RATS Photos courtesy Jiri Lochman,Transparencies Lochman Australia’s native rodents are the most ecologically diverse family of Australian mammals. There are about 60 living species – all within the subfamily Murinae – representing around 25 per cent of all species of Australian mammals.They range in size from the very small delicate mouse to the highly specialised, arid-adapted hopping mouse, the large tree rat and the carnivorous water rat. Native Mice and Rats describes the evolution and ecology of this much-neglected group of animals. It details the diversity of their reproductive biology, their dietary adaptations and social behaviour. The book also includes information on rodent parasites and diseases, and concludes by outlining the changes in distribution of the various species since the arrival of Europeans as well as current conservation programs. Bill Breed is an Associate Professor at The University of Adelaide. He has focused his research on the reproductive biology of Australian native mammals, in particular native rodents and dasyurid marsupials. Recently he has extended his studies to include rodents of Asia and Africa. Fred Ford has trapped and studied native rats and mice across much of northern Australia and south-eastern New South Wales. He currently works for the CSIRO Australian National Wildlife Collection. BILL BREED AND FRED FORD NATIVE MICE AND RATS Native Mice 4thpp.indd i 15/11/07 2:22:35 PM Native Mice 4thpp.indd ii 15/11/07 2:22:36 PM AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES NATIVE MICE AND RATS BILL BREED AND FRED FORD Native Mice 4thpp.indd iii 15/11/07 2:22:37 PM © Bill Breed and Fred Ford 2007 All rights reserved. -

Woinarski, JCZ, Braby, MF, Burbidge, AA, Coates, D., Garnett, ST

Woinarski, J.C.Z., Braby, M.F., Burbidge, A.A., Coates, D., Garnett, S.T., Fensham, R.J., Legge, S.M., McKenzie, N.L., Silcock, J.L., and Murphy, B.P. (2019). Reading the black book: the number, timing, distribution and causes of listed extinctions in Australia. Biological Conservation. Vol. 239, 108261 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108261 © 2019. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 1 2 3 Reading the black book: the number, timing, distribution and causes of listed 4 extinctions in Australia 5 6 7 8 9 J.C.Z. Woinarski1, M.F. Braby2, A.A. Burbidge3, D. Coates4, S.T. Garnett1, R.J. Fensham5, S.M. 10 Legge5, N.L. McKenzie6, J.L. Silcock5, and B.P. Murphy1 11 12 13 1. NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, 14 Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia 15 2. Division of Ecology and Evolution, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, 16 Acton, ACT 2601, Australia 17 3. 87 Rosedale St., Floreat, WA, 6014, Australia 18 4. Biodiversity and Conservation Science, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, 19 17 Dick Perry Ave, Kensington, WA 6151, Australia 20 5. NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Research, 21 University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia 22 6. Woodvale Research Centre, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Wildlife 23 Place, Woodvale 6026, Australia 24 25 26 1 27 28 29 Abstract 30 31 Through collation of global, national and state/territory threatened species lists, we conclude that 32 100 Australian endemic species (one protist, 38 vascular plants, ten invertebrates, one fish, four 33 frogs, three reptiles, nine birds and 34 mammals) are validly listed as extinct (or extinct in the wild) 34 since the nation’s colonisation by Europeans in 1788. -

HANDBOOK of the MAMMALS of the WORLD Families of Volume 1: Carnivores

HANDBOOK OF THE MAMMALS OF THE WORLD Families of Volume 1: Carnivores Family Family English Subfamily Group name Species Genera Scientific name name number African Palm NANDINIIDAE 1 species Nandinia Civet Neofelis Pantherinae Big Cats 7 species Panthera Pardofelis Catopuma FELIDAE Cats Leptailurus Profelis Caracal Leopardus Felinae Small Cats 30 species Lynx Acinonyx Puma Otocolobus Prionailurus Felis PRIONODONTIDAE Linsangs 2 species Prionodon Viverricula Viverrinae Terrestrial Civets 6 species Civettictis Viverra Poiana Genettinae Genets and Oyans 17 species Genetta Civets, Genets VIVERRIDAE and Oyans Arctogalidia Macrogalidia Palm Civets and Paradoxurinae 7 species Arctictis Binturong Paguma Paradoxurus Cynogale Palm Civets and Chrotogale Hemigalinae 4 species Otter Civet Hemigalus Diplogale Family Family English Subfamily Group name Species Genera Scientific name name number Protelinae Aardwolf 1 species Proteles HYAENIDAE Hyenas Crocuta Bone-cracking Hyaeninae 3 species Hyaena Hyenas Parahyaena Atilax Xenogale Herpestes Cynictis Solitary Herpestinae 23 species Galerella Mongooses Ichneumia Paracynictis HERPESTIDAE Mongooses Bdeogale Rhynchogale Suricata Crossarchus Social Helogale Mungotinae 11 species Mongooses Dologale Liberiictis Mungos Civet-like Cryptoprocta Euplerinae Madagascar 3 species Eupleres Carnivores Fossa Madagascar EUPLERIDAE Carnivores Galidia Mongoose-like Galidictis Galidinae Madagascar 5 species Mungotictis Carnivores Salanoia Canis Cuon Lycaon Chrysocyon Speothos Cerdocyon CANIDAE Dogs 35 species Atelocynus Pseudalopex