Report to the Faculty, Administration, Trustees, Students Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Michael D. Robinson Department of Economics 197 Mosier St. Mount Holyoke College South Hadley, MA 01075 South Hadley, MA 01075 (413) 533-5052 (413) 538-3085 [email protected] Education Ph.D. (Economics), University of Texas at Austin. Dissertation: A Regional Analysis of Male-Female Earnings Differentials. Supervisor: Niles Hansen. May 1987. B.A. (Economics), Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri. Magna Cum Laude. 1979. Research Interests Applied Microeconomics (Labor) Applied Econometrics Economics of Higher Education Areas of Teaching Interest Microeconomic Theory/Principles Labor Economics Econometrics/Statistics Women in the Economy Prizes and Awards Meribeth E. Cameron Faculty Prize for Scholarship, 2004 Experience 2000-Present. Professor of Economics, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts. 1993-2000. Associate Professor of Economics, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts. 2 1995-1998. Senior Advisor to the President on Enrollment Planning, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts. 1988-1992. Assistant Professor of Economics, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts. Spring 1989. Visiting Assistant Professor of Economics, Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut. 1987-1988. Visiting Assistant Professor of Economics, Middlebury College, Middlebury, Vermont. Publications Refereed Articles “Empirical Evidence of the Effects of Marriage on Male and Female Attendance at Sports and Arts.” with Sally Montgomery. (March 2010) Social Science Quarteryly. Vol. 91, No. 1, pp 99-116. “Increasing Study Abroad: Participation.” (with Eva Paus) Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal Study Abroad, Volume XVII, Fall 2008, pp.33-50. “Which Countries are Studied Most by Economists? An Examination of the Regional Distribution of Economic Research,” (with James Hartley and Patricia Schneider) Kyklos,Vol. 59, Issue 4, Page 611, November 2006. -

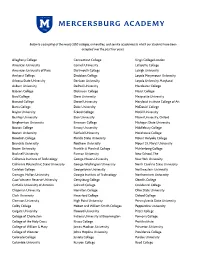

Below Is a Sampling of the Nearly 500 Colleges, Universities, and Service Academies to Which Our Students Have Been Accepted Over the Past Four Years

Below is a sampling of the nearly 500 colleges, universities, and service academies to which our students have been accepted over the past four years. Allegheny College Connecticut College King’s College London American University Cornell University Lafayette College American University of Paris Dartmouth College Lehigh University Amherst College Davidson College Loyola Marymount University Arizona State University Denison University Loyola University Maryland Auburn University DePaul University Macalester College Babson College Dickinson College Marist College Bard College Drew University Marquette University Barnard College Drexel University Maryland Institute College of Art Bates College Duke University McDaniel College Baylor University Eckerd College McGill University Bentley University Elon University Miami University, Oxford Binghamton University Emerson College Michigan State University Boston College Emory University Middlebury College Boston University Fairfield University Morehouse College Bowdoin College Florida State University Mount Holyoke College Brandeis University Fordham University Mount St. Mary’s University Brown University Franklin & Marshall College Muhlenberg College Bucknell University Furman University New School, The California Institute of Technology George Mason University New York University California Polytechnic State University George Washington University North Carolina State University Carleton College Georgetown University Northeastern University Carnegie Mellon University Georgia Institute of Technology -

Founded by Abolitionists, Funded by Slavery: Past and Present Manifestations of Bates College’S Founding Paradox

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 Founded by Abolitionists, Funded by Slavery: Past and Present Manifestations of Bates College’s Founding Paradox Emma Soler Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Soler, Emma, "Founded by Abolitionists, Funded by Slavery: Past and Present Manifestations of Bates College’s Founding Paradox" (2020). Honors Theses. 321. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/321 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Founded by Abolitionists, Funded by Slavery: Past and Present Manifestations of Bates College’s Founding Paradox An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program Bates College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Emma Soler Lewiston, Maine April 1, 2020 1 Acknowledgements Thank you to Joe, who inspired my interest in this topic, believed in me for the last three years, and dedicated more time and energy to this thesis than I ever could have asked for. Thank you to Ursula, who through this research became a partner and friend. Thank you to Perla, Nell, Annabel and Ke’ala, all of whom made significant contributions to this work. Thank you to the other professors who have most shaped my worldview over the past four years: Christopher Petrella, Yannick Marshall, David Cummiskey, Sonja Pieck, Erica Rand, Sue Houchins, Andrew Baker, and Anelise Shrout. -

1989 Through 2004

United States Intercollegiate Lacrosse Association Scholar All-American 1989 Malcolm Lester Springfield College Michael Ruland Loyola College Eric J. Stein Hobart College Shawn A. Trell Hobart College 1990 Tom Barnds Princeton University Reid Campbell Washington & Lee University Tom Hormes Washington College 1991 Joe Alberici Alfred University Thomas N. Groeninger University of Virginia Brentnall M. Powell Williams College John R. Quinn United States Naval Academy Michael J. Schattner University of Virginia 1992 Brian K. Bugge St. John’s University Scott Giardina Johns Hopkins University George S. Glyphis University of Virginia Clark J. Hospelhorn Western Maryland College Jonathan H. Owsley Middlebury College Sean M. Quinn Loyola College David Ryan Yale University Justin Tortolani Princeton University Gregory R. Waller Princeton University 1993 Kevin Beach Loyola College Daniel Hinds Bowdoin College John Hunter Washington & Lee University Chris Marcus Penn State University 1994 Scott Bacigalupo Princeton University William Carty USMMA Matthew Daniels Rochester Institute of Technology Andrew McDonald Williams College Ted Nusbaum Colorado College Thomas Pena Hobart College Peter Ramsey Princeton University Scott Reinhardt Princeton University Craig Ronald University of Virginia David Scheid Cornell University Taylor Simmers Princeton University Sean Turner West Point Justin Zackery Bucknell University 1995 Ryan B. Adams Clarkson University Damien T. DePeter Connecticut College Paul S. Goggi LeMoyne College Scott Harrison Duke University -

College Counseling Program

College Counseling Program The Oregon Episcopal School college counseling team works closely with students as they search for colleges in which they will thrive. Encouraging them to take ownership of the experience, we combine individualized advice with programs and resources designed to help students—and their families—navigate the search and application phases in a thoughtful manner. Throughout high school, we provide guidance, perspective, and timely information intended to demystify the process and encourage wise choices. Underpinning our approach is a desire to have students make the most of their high school experience in a healthy, balanced manner. COLLEGE NIGHTS FOR PARENTS We offer workshops for parents, tailored by grade level, to learn about the college search process, and a presentation on financing college. For more information, visit: COLLEGE ATTENDANCE oes.edu/college Graduates of OES attend an impressive array of colleges throughout the United States and internationally. OES has an excellent, well-established reputation with colleges across the country and hosts visits from over 130 college representatives in a typical year. Colleges Attended Public vs. Private Public 29% 71% Private Non U.S.: 4% Admissions 6300 SW Nicol Road | Portland, OR 97223 | 503-768-3115 | oes.edu/admissions OES STUDENTS FROM THE CLASSES OF 2020 AND 2021 WERE ACCEPTED TO THE FOLLOWING COLLEGES Acadia University Elon University Pomona College University of Chicago Alfred University Emerson College Portland State University University of Colorado, -

Archived News

Archived News 2011-2012 News articles from 2011-2012 Table of Contents Lauren Busser '12 talks about the fears and hopes Nicoletta Barolini '83 interviewed by Bronxville of a college senior ............................................... 9 Patch about "Flatlands" exhibit........................ 19 Literature faculty member Nicolaus Mills The Los Angeles Times calls writing professor compares Obama's reelection campaign to that of Scott Snyder "one of the fastest-rising stars in FDR in Dissent.................................................... 9 comics" ............................................................. 19 Sabina Amidi '11 and Kayla Malahiazar '12 Gary Ploski MFA '08 wins best acting honors for explore Beirut's LGBT community in new short film Objects of Time ................................ 19 documentary........................................................ 9 Tennis players Maddy Dessanti '14 and Kayla Writing faculty member Scott Snyder revamps Pincus '15 take home conference honors for Batman and Swamp Thing for DC Comics......... 9 excellent play.................................................... 20 Cellist Zoe Keating '93 profiled on NPR's All Americans for UNFPA's 2011 international Things Considered ............................................ 10 honorees to speak at SLC ................................. 21 Alexandra Pezenik '14 "Spotted on the Street" by Author to speak about Eleanor Roosevelt on The New York Times ......................................... 10 October 11 ....................................................... -

Colby College Catalogue 1967 - 1968

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Catalogues Colby College Archives 1967 Colby College Catalogue 1967 - 1968 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/catalogs Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby College Catalogue 1967 - 1968" (1967). Colby Catalogues. 80. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/catalogs/80 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Catalogues by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. I COLBY COLLEGE BULLETIN 'A TERVILLE, MA INE•FOUNDED IN 1813 •ANNUAL CA TALOGUE ISSUE• SEPTEMBER, 1967 2 I COLBY COLLEGE: INQUIRIES Inquiries to the college should be directed as follows: ADMISSION HARRY R. CARROLL, Dean of Admissions ADULT EDUCATION AND JOHN B. SIMPSON, Director of Summer and Special Programs SUMMER PROGRAMS FINANCIAL ARTHUR W. SEEPE, Treasurer HEALTH AND CARL E. NELSON, Director of Health Services MEDICAL CARE HOUSING FRANCES F. SEAMAN (MRs.), Dean of Students PLACEMENT EARLE A. McKEEN, Director of Career Planning and Placement RECORDS AND TRANSCRIPTS GEORGE L. CoLEMAN, Registrar SCHOLARSHIPS AND CHARLES F . H1cKox, JR., Director of Financial Aid and EMPLOYMENT Coordinator of Government-Supported Programs SUMMER SCHOOL OF Director of the Summer School of Languages LANGUAGES ' VETERANS AFFAIRS GEORGE L. COLEMAN, Registrar A booklet, ABOUT COLBY, with illustrative material, has been prepared for prospective students and may be obtained from the dean of admissions. College address: Colby College, Waterville, Maine 04901. SERIES 66 The COLBY COLLEGE BULLETIN is published five times yearly, in: May, June, September, December, and March. -

Hiram E. Chodosh ______HIRAM E

Hiram E. Chodosh ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ HIRAM E. CHODOSH PRESIDENT AND PROFESSOR OF THE COLLEGE CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Claremont McKenna College, Claremont, California President and Professor of the College (from July 2013) Chair, Council of Presidents, The Claremont Colleges (2016-2017) University of Utah, S.J. Quinney College of Law, Salt Lake City, Utah (2006-2013) Dean and Hugh B. Brown Presidential Professor of Law Senior Presidential Adviser on Global Strategy Case Western Reserve University School of Law, Cleveland, Ohio (1993-2006) Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Joseph C. Hostetler–Baker & Hostetler Professor of Law Director, Frederick K. Cox International Law Center Indian Law Institute, New Delhi, India, (2003) Fulbright Senior Scholar Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton, New York City (1990-1993) Associate Orion Consultants, Inc., New York City (1985-1987) Management Consultant GLOBAL JUSTICE ADVISORY EXPERIENCE Government of Iraq, Director, Global Justice Project: Iraq (2008-2010) United Nations Development Program (Asia), Adviser (2006-2007) World Bank Group, Adviser (2005-2006) International Monetary Fund, Adviser (1999-2004) U.S. State Department, Rapporteur (1993-2003) Page 1 of 25 Hiram E. Chodosh ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

TRANSCRIPT KEY ALL DEGREES INFORMATION UNDERGRADUATE DEGREES INFORMATION Bachelor of Arts Course Grades: B.A.,BLS, M.A., Ph.D

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR TRANSCRIPT KEY ALL DEGREES INFORMATION UNDERGRADUATE DEGREES INFORMATION Bachelor of Arts Course Grades: B.A.,BLS, M.A., Ph.D. Bachelor of Liberal Studies Letter Description Percentage Office of the Registrar: (860) 685-2810 A Excellent 95 B Good 85 For students entering in or after the fall of 2000 the graduation requirements for the C Fair 75 Bachelor (BA, BLS) degree is the satisfactory completion of 32 course credits. From D Unsatisfactory Pass 65 September 1963 until May 2000, the graduation requirement was the satisfactory E Failure 55 completion of 34 course credits. The unit of credit is the semester-course. Academic F Bad Failure 45 work prior to September 1963 and transfer course work for which hour credit was These letter grades may be qualified by the use of plus and minus signs. The awarded have been converted to Wesleyan course equivalents. percentage values are as follows: A+: 98.3, A-: 91.7, etc. For students entering in or after the fall of 2000 each Wesleyan course credit is worth Other symbols used: 4.00 semester-hours and 6.00 quarter-hours. For students who entered prior to the fall CR - Credit without Grade of 2000 each Wesleyan course credit is worth 3.50 semester-hours or 5.50 quarter- P - Passing but No Credit hours. U - Unsatisfactory, No Credit AU - Auditor in Course, No Credit Beginning with the academic year 1963-64, courses that include a scheduled IN - Incomplete laboratory of three or more hours weekly are indicated by the notation LAB following W - Withdrew from Course, No Credit the course title. -

Report of the Working Group on Williams in The

DRAFT Report of the Working Group Williams in the World Working Group Members: Jackson Ennis, Class of 2020 Jim Kolesar ’72, Office of the President Colin Ovitsky, Center for Learning in Action Noah Sandstrom, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience Program Sharifa Wright ’03, Alumni Relations February 2020 1 Table of Contents Background……………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Our Work…………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Themes……………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Aspirations for the next decade……………………………………………………………………7 Guiding Principles………………………………………………………………………………... 9 Recommendations……………………………………………………………………………….. 12 To Close…………………………………………………………………………………………. 14 Appendices 1: Williams in the World charge………………………………..……………………….…........ 15 2: Summary of Outreach…………………………………………………………………….…. 16 3: Tactical and Tangible Ideas That Arose From Outreach……………………………….……. 18 4: Centers for Engaged Learning or Scholarship at Several Peer Schools……………………... 21 2 Background The story of Williams’s engagement in the world is long and interesting. We have space here only to summarize it. For most of its life, Williams understood itself as a “college on a hill.” Students withdrew here to contemplate higher things before heading back into the “real world.” The vocation of faculty was to pass on that knowledge, while staff supported the operation by managing the day-to-day. Over time, however, all of these lines blurred. The beginning may have come in the early 1960s, when students formed the Lehman Service Council to organize their projects in the local community. Two student-initiated programs, the Williamstown Youth Center and the Berkshire Food Project, still thrive. In the way that the student-formed Lyceum of Natural History, some of whose interactions with other cultures we now question, eventually led to the introduction of science into the curriculum, so too in time did the engagement seed germinated in the Lehman Council disperse widely through the college. -

Engaged with the World: a Strategic Plan for Wesleyan University, 2005-2010

ENGAGED WITH THE WORLD: A STRATEGIC PLAN FOR WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY, 2005-2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. OVERVIEW 1-4 II. ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE 5-13 A. Strengthen the Essential Capabilities B. Prepare our Students to Be Engaged in a Global Society C. Increase Student Participation in Sciences and Build Science Facilities to Accommodate New Needs D. Use Advising to Strengthen Curricular Goals E. Improve Curricular Choices and Enhance Faculty Resources F. Add Infrastructure to Support Learning, Teaching, and Scholarship Provide Academic Resources to Support Today’s Students Capitalize on Successful Library and ITS Collaboration to Improve Services Enhance the Use of Technology as a Pedagogical Tool Create a Secure Foundation for the Center for Faculty Career Development III. CAMPUS COMMUNITY 13-18 A. Enhance Admission Competitiveness and Outreach B. Engage Diversity as an Educational Asset C. Facilitate Interaction of Faculty and Students Outside of the Classroom D. Build and Remodel Residential Facilities to Support Educational Initiatives E. Strengthen and Develop Environmental Stewardship IV. EXTERNAL RELATIONS 18-21 A. Strengthen the Ties between Wesleyan and the Middletown Community Expand Volunteerism Continue Collaboration in Main Street Initiatives Continue Collaboration in Green Street Arts Center B. Expand Wesleyan’s Presence in the Region through Continuing Studies C. Strengthen Wesleyan's Presence in State and Federal Educational Matters V. EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL COMMUNICATIONS 21-23 A. Increase Visibility in the Public Media B. Deepen Alumni and Parent Engagement through Improved Communications C. Improve Internal Communications 1 Strategic Plan VI. FACILITIES 23-24 VII. FINANCE 24 VIII. FUNDRAISING CAPABILITY 24-25 APPENDICES 1. Essential Capabilities 26-27 2. -

2021-2022 Colby College Catalogue

2021-2022 Colby College Catalogue Colby College 1 2021-2022 Catalogue ABOUT COLBY Founded in 1813, Colby College is the 12th oldest liberal arts college in the United States. Distinctive in its offerings, Colby provides an intimate, undergraduate-focused learning environment with a breadth of programs presenting students and faculty with unparalleled opportunities. A vibrant and fully integrated academic, residential, and cocurricular experience is sustained by a diverse and supportive community. Located in Waterville, Maine, Colby is a global institution with students representing nearly every U.S. state and approximately 70 countries. Colby’s model provides the scale and impact of larger universities coupled with intensive learning in a community committed to scholarship and discovery, multidisciplinary approaches to integrated learning, study in the liberal arts, and leading-edge programs addressing the world’s most complex challenges. Its network of partnerships with prestigious cultural, research, medical, and business institutions extends educational and scholarly collaborations, providing students with unmatched experiences leading to postgraduate success. The College’s wide variety of programs and labs provides students and the community access to unique experiences: the Colby College Museum of Art, the finest college art museum in the country, and the Lunder Institute for American Art have made the College a nationally and internationally recognized center for art scholarship; DavisConnects prepares students for lifelong success by combining a forward- thinking liberal arts education with extensive internship, research, and global opportunities for all students regardless of their personal networks and financial circumstances; and the 350,000-square-foot Harold Alfond Athletics and Recreation Center, opened in 2020, is the most advanced and comprehensive NCAA D-III facility in the country.