{PDF EPUB} Anthropomorphisms by Bruce Boston Anthropomorphisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Crowley Program Guide Program Guide

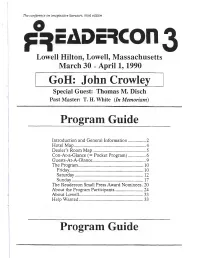

The conference on imaginative literature, third edition pfcADcTCOn 3 Lowell Hilton, Lowell, Massachusetts March 30 - April 1,1990 GoH: John Crowley Special Guest: Thomas M. Disch Past Master: T. H. White (In Memoriam) Program Guide Introduction and General Information...............2 Hotel Map........................................................... 4 Dealer’s Room Map............................................ 5 Con-At-a-Glance (= Pocket Program)...............6 Guests-At-A-Glance............................................ 9 The Program...................................................... 10 Friday............................................................. 10 Saturday.........................................................12 Sunday........................................................... 17 The Readercon Small Press Award Nominees. 20 About the Program Participants........................24 About Lowell.....................................................33 Help Wanted.....................................................33 Program Guide Page 2 Readercon 3 Introduction Volunteer! Welcome (or welcome back) to Readercon! Like the sf conventions that inspired us, This year, we’ve separated out everything you Readercon is entirely volunteer-run. We need really need to get around into this Program (our hordes of people to help man Registration and Guest material and other essays are now in a Information, keep an eye on the programming, separate Souvenir Book). The fact that this staff the Hospitality Suite, and to do about a Program is bigger than the combined Program I million more things. If interested, ask any Souvenir Book of our last Readercon is an committee member (black or blue ribbon); they’ll indication of how much our programming has point you in the direction of David Walrath, our expanded this time out. We hope you find this Volunteer Coordinator. It’s fun, and, if you work division of information helpful (try to check out enough hours, you earn a free Readercon t-shirt! the Souvenir Book while you’re at it, too). -

Carlos Germán Belli

Índice: • Poesía Especulativa. Wikipedia • Oscuridad. Lord Byron • Soneto a la ciencia / El gusano vencedor / La ciudad en el mar. Egdar Allan Poe. • Hongos de Yuggoth. Poemas de horror cósmico. H.P. Lovercraft • El camino de los reyes. Robert E. Howard. • Desde las criptas de la memoria / La antigua búsqueda. Clark Ashton Smith • Vendrán lluvias suaves. Sara Teasdal • Poema nocturno / Quema de lechuzas / La soledad del historiador bélico. Margaret Atwood • Acerca de la poesía de Ciencia Ficción. Suzette Haden Elgin • Zimmer No. 20 / Sueños / Tiempo puente en la Civoccid. Brian W. Aldiss • El Manifiesto del Haikú de Ciencia ficción. Tom Brinck • Poesía de ciencia ficción hispanoamericana. 1. Estrellas que entre lo sombrío... José Asunción Silva (Colombia) 2. Yo estaba en el espacio. Amado Nervo. (México) 3. El poema de robot. Leopoldo Marechal. (Argentina) 4. Oh hada cibernética. Carlos Germán Belli. (Perú) 5. LEDH-9. Cristina Camacho Fahsen (Guatemala) 6. Sirio. Antonio Mora Velez (Colombia) 7. El bastión. J. Javier Arnau (España) 8. Coplas por los días en que dictará el Apocalipsis. Micaela Romani (Argentina) • Diálogos por la luz de las estrellas. Tres enfoques para escribir poesía de Ciencia ficción. Suzette Haden Elgin • Historia del cine ciberpunk. 1995. Death Machine (Máquina letal). Para descargar números anteriores de Qubit, visitar http://www.eldiletante.co.nr Para subscribirte a la revista, escribir a [email protected] 3 POESÍA ESPECULATIVA De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre También llamada indistintamente poesía de ciencia ficción, poesía fantástica o poesía CF, la poesía especulativa es para la poesía lo mismo que la ficción especulativa es a la ficción. -

February 2016 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle February 2016 The Next NASFA Meeting is 6:30P Saturday 20 February 2016 at the Regular Location Concom Meeting 3P at the Church, 20 February 2016 FUTURE CLUB MEETING DATES d Oyez, Oyez d Three 2016 NASFA meetings have been changed off of the ! normal 3rd Saturday due to convention conflicts: The next NASFA Meeting will be 20 February 2016, at the • The March 2016 meeting will be on the 26th, one week later regular meeting location—the Madison campus of Willow- than usual due to MidSouthCon. brook Baptist Church (old Wilson Lumber Company building) • The August 2016 meeting will be on the 13th, one week ear- at 7105 Highway 72W (aka University Drive). lier than usual due to Worldcon. FEBRUARY PROGRAM • The October 2016 meeting will be on the 22nd, one week The February program is TBD at press time, though it is later than usual due to Con†Stellation. known that JudySue is working on something. JANUARY ATMM Mary and Doug Lampert will host the January After-The- Meeting Meeting, at the meeting site. The usual rules apply— Road Jeff Kroger that is, please bring food to share and your favorite drink. Also, please stay to help clean up. We need to be good guests and leave things at least as clean as we found them. US 72W CONCOM MEETINGS (aka University Drive) The first Con†Stellation XXXIV Concom Meeting will be 3P on 20 February 2016—the same day as the club meeting. Going forward, it is expected that concom meetings will con- tinue to be on NASFA meeting days, at least until we get close Road Slaughter enough to the con to need to meet twice a month. -

36.2 $5.00 April 2013

April 2013 36.2 $5.00 Poetry by Ed Binkley 4 Wyrms & Wormholes — F.J. Bergmann 7 President’s Message — David C. Kopaska-Merkel 12 Elgin Awards Announcement 13 From the Small Press — David C. Kopaska-Merkel, Joshua Gage, Wendy Rathbone, Bryan Thao Worra, Terrie Leigh Relf, John Garrison, Susan Gabrielle 46 Xenopoetry — translation by Fred W. Bergmann Poetry 3 “Transmuter backed up” — David C. Kopaska-Merkel 6 I’m the Stone You Can Squeeze Blood from — Sarah Terry 8 Making Amends — Jason Sturner 9 Black Sabbath Sestina — Wade German 11 Don’t Think There’s Nothing to Fear — Kurt MacPhearson 11 Moon Jim Skinhead — John W. Sexton 11 “relearning farming” — David C. Kopaska-Merkel 11 New and Improved — David Dickinson 17 Mississippi Twilight — Chad Hensley • “green thumb” — LeRoy Gorman 18 My Blind Desire for the Fleeting — Robert Frazier 19 General Curse against One Who Has Tried to Harm You — Margaret Benbow 19 Ifrit — Jason Matthews 19 Oregon 2112 — Harvey J. Baine 20 Superiority Is Relative — Robert Laughlin 20 Terran delegation — Lauren McBride • Workshop — Lenore McComas Coberley 21 Our Hearts Cried Out — Alicia Cole 21 Who’s for Dinner — David C. Kopaska-Merkel 22 Interpose: A Love Poem — Scott T. Hutchison 23 His Majesty — Justin Hamm • Advice from the future — Damien Cowger 23 Famers — Vincent Miskell • “game for the outer world cup” — LeRoy Gorman 24 Towers of Light — Ann K. Schwader 25 In Monster Years, I’m Old — Lauren McBride 25 “the dogs go quack” — Kim L. Neidigh 25 The Truth about Fairies —Beth Cato • Old Fashions — Neal Wilgus 26 Keeping Company — Jarod K.