SACRED SPACES and RITUALS: EARLY CHRISTIAN ART and ARCHITECTURE (Early Christian Basilicas and Manuscripts) Early Christian Basilicas and Manuscripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained a Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D

Welcome to OUR 4th VIRTUAL GSP class. Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained A Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D. Lord Jesus Christ, may our church be a temple of your presence and a house of prayer. Be always near us when we seek you in this place. Draw us to you, when we come alone and when we come with others, to find comfort and wisdom, to be supported and strengthened, to rejoice and give thanks. May it be here, Lord Christ, that we are made one with you and with one another, so that our lives are sustained and sanctified for your service. Amen. HISTORY OF CHURCH BUILDINGS The Bible's authors never thought of the church as a building. To early Christians the word “church” referred to the act of assembling together rather than to the building itself. As long as the Roman government did not did not recognize and protect Christian places of worship, Christians of the first centuries met in Jewish places of worship, in privately owned houses, at grave sites of saints and loved ones, and even outdoors. In Rome, there are indications that early Christians met in other public spaces such as warehouses or apartment buildings. The domus ecclesiae or house church was a large private house--not just the home of an extended family, its slaves, and employees--but also the household’s place of business. Such a house could accommodate congregations of about 100-150 people. 3rd-century house church in Dura-Europos, in what is now Syria CHURCH BUILDINGS In the second half of the 3rd century, Christians began to construct their first halls for worship (aula ecclesiae). -

Profile of a Plant: the Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE By

Profile of a Plant: The Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE by Benjamin Jon Graham A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paolo Squatriti, Chair Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes Professor Richard P. Tucker Professor Raymond H. Van Dam © Benjamin J. Graham, 2014 Acknowledgements Planting an olive tree is an act of faith. A cultivator must patiently protect, water, and till the soil around the plant for fifteen years before it begins to bear fruit. Though this dissertation is not nearly as useful or palatable as the olive’s pressed fruits, its slow growth to completion resembles the tree in as much as it was the patient and diligent kindness of my friends, mentors, and family that enabled me to finish the project. Mercifully it took fewer than fifteen years. My deepest thanks go to Paolo Squatriti, who provoked and inspired me to write an unconventional dissertation. I am unable to articulate the ways he has influenced my scholarship, teaching, and life. Ray Van Dam’s clarity of thought helped to shape and rein in my run-away ideas. Diane Hughes unfailingly saw the big picture—how the story of the olive connected to different strands of history. These three people in particular made graduate school a humane and deeply edifying experience. Joining them for the dissertation defense was Richard Tucker, whose capacious understanding of the history of the environment improved this work immensely. In addition to these, I would like to thank David Akin, Hussein Fancy, Tom Green, Alison Cornish, Kathleen King, Lorna Alstetter, Diana Denney, Terre Fisher, Liz Kamali, Jon Farr, Yanay Israeli, and Noah Blan, all at the University of Michigan, for their benevolence. -

Turkey: the World’S Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013 Global Heritage Fund Turkey: the World’S Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013

Global Heritage Fund Turkey: The World’s Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013 Global Heritage Fund Turkey: The World’s Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013 To overstate the depth of Turkey’s culture or the richness of its history is nearly impossible. At the crossroads of two continents, home to some of the world’s earliest and most influential cities and civilizations, Turkey contains multi- tudes. The graciousness of its people is legendary—indeed it’s often said that to call a Turk gracious is redundant—and perhaps that’s no surprise in a place where cultural exchange has been taking place for millennia. From early Neolithic ruins to vibrant Istanbul, the karsts and cave-towns of Cappadocia to metropolitan Ankara, Turkey is rich in treasure for the inquisi- tive traveler. During our explorations of these and other highlights of the coun- FEATURING: try, we will enjoy special access to architectural and archaeological sites in the Dan Thompson, Ph.D. company of Global Heritage Fund staff. Director, Global Projects and Global Heritage Network Dr. Dan Thompson joined Global Heritage Fund full time in January 2008, having previously conducted fieldwork at GHF-supported projects in the Mirador Basin, Guatemala, and at Ani and Çatalhöyük, both in Turkey. As Director of Global Projects and Global Heri- tage Network (GHN), he oversees all aspects of GHF projects at the home office, manages Global Heritage Network, acts as senior editor of print and web publica- tions, and provides support to fundraising efforts. Dan has BA degrees in Anthropology/Geography and Journalism, an MA in Near Eastern Studies from UC Berkeley, and a Ph.D. -

Rome: a Pilgrim’S Guide to the Eternal City James L

Rome: A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Eternal City James L. Papandrea, Ph.D. Checklist of Things to See at the Sites Capitoline Museums Building 1 Pieces of the Colossal Statue of Constantine Statue of Mars Bronze She-wolf with Twins Romulus and Remus Bernini’s Head of Medusa Statue of the Emperor Commodus dressed as Hercules Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Statue Statue of Hercules Foundation of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus In the Tunnel Grave Markers, Some with Christian Symbols Tabularium Balconies with View of the Forum Building 2 Hall of the Philosophers Hall of the Emperors National Museum @ Baths of Diocletian (Therme) Early Roman Empire Wall Paintings Roman Mosaic Floors Statue of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus (main floor atrium) Ancient Coins and Jewelry (in the basement) Vatican Museums Christian Sarcophagi (Early Christian Room) Painting of the Battle at the Milvian Bridge (Constantine Room) Painting of Pope Leo meeting Attila the Hun (Raphael Rooms) Raphael’s School of Athens (Raphael Rooms) The painting Fire in the Borgo, showing old St. Peter’s (Fire Room) Sistine Chapel San Clemente In the Current Church Seams in the schola cantorum Where it was Cut to Fit the Smaller Basilica The Bishop’s Chair is Made from the Tomb Marker of a Martyr Apse Mosaic with “Tree of Life” Cross In the Scavi Fourth Century Basilica with Ninth/Tenth Century Frescos Mithraeum Alleyway between Warehouse and Public Building/Roman House Santa Croce in Gerusalemme Find the Original Fourth Century Columns (look for the seams in the bases) Altar Tomb: St. Caesarius of Arles, Presider at the Council of Orange, 529 Titulus Crucis Brick, Found in 1492 In the St. -

Spolia's Implications in the Early Christian Church

BEYOND REUSE: SPOLIA’S IMPLICATIONS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN CHURCH by Larissa Grzesiak M.A., The University of British Columba, 2009 B.A. Hons., McMaster University, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Art History) THE UNVERSIT Y OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2011 © Larissa Grzesiak, 2011 Abstract When Vasari used the term spoglie to denote marbles taken from pagan monuments for Rome’s Christian churches, he related the Christians to barbarians, but noted their good taste in exotic, foreign marbles.1 Interest in spolia and colourful heterogeneity reflects a new aesthetic interest in variation that emerged in Late Antiquity, but a lack of contemporary sources make it difficult to discuss the motives behind spolia. Some scholars have attributed its use to practicality, stating that it was more expedient and economical, but this study aims to demonstrate that just as Scripture became more powerful through multiple layers of meaning, so too could spolia be understood as having many connotations for the viewer. I will focus on two major areas in which spolia could communicate meaning within the context of the Church: power dynamics, and teachings. I will first explore the clear ecumenical hierarchy and discourses of power that spolia delineated through its careful arrangement within the church, before turning to ideological implications for the Christian viewer. Focusing on the Lateran and St. Peter’s, this study examines the religious messages that can be found within the spoliated columns of early Christian churches. By examining biblical literature and patristic works, I will argue that these vast coloured columns communicated ideas surrounding Christian doctrine. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

Pevsner's Architectural Glossary

Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 1 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 2 Nikolaus and Lola Pevsner, Hampton Court, in the gardens by Wren's east front, probably c. Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 3 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Yale University Press New Haven and London Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 4 Temple Street, New Haven Bedford Square, London www.pevsner.co.uk www.lookingatbuildings.org.uk www.yalebooks.co.uk www.yalebooks.com for Published by Yale University Press Copyright © Yale University, Printed by T.J. International, Padstow Set in Monotype Plantin All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 5 CONTENTS GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 6 FOREWORD The first volumes of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Buildings of England series appeared in .The intention was to make available, county by county, a comprehensive guide to the notable architecture of every period from prehistory to the present day. Building types, details and other features that would not necessarily be familiar to the general reader were explained in a compact glossary, which in the first editions extended to some terms. -

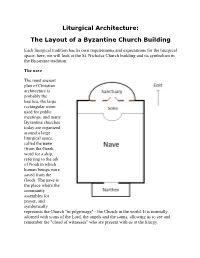

Liturgical Architecture: the Layout of a Byzantine Church Building

Liturgical Architecture: The Layout of a Byzantine Church Building Each liturgical tradition has its own requirements and expectations for the liturgical space; here, we will look at the St. Nicholas Church building and its symbolism in the Byzantine tradition. The nave The most ancient plan of Christian architecture is probably the basilica, the large rectangular room used for public meetings, and many Byzantine churches today are organized around a large liturgical space, called the nave (from the Greek word for a ship, referring to the ark of Noah in which human beings were saved from the flood). The nave is the place where the community assembles for prayer, and symbolically represents the Church "in pilgrimage" - the Church in the world. It is normally adorned with icons of the Lord, the angels and the saints, allowing us to see and remember the "cloud of witnesses" who are present with us at the liturgy. At St. Nicholas, the nave opens upward to a dome with stained glass of the Eucharist chalice and the Holy Spirit above the congregation. The nave is also provided with lights that at specific times the church interior can be brightly lit, especially at moments of great joy in the services, or dimly lit, like during parts of the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts. The nave, where the congregation resides during the Divine Liturgy, at St. Nicholas is round, representing the endlessness of eternity. The principal church building of the Byzantine Rite, the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, employed a round plan for the nave, and this has been imitated in many Byzantine church buildings. -

Liturgy, Space, and Community in the Basilica Julii (Santa Maria in Trastevere)

DALE KINNEY Liturgy, Space, and Community in the Basilica Julii (Santa Maria in Trastevere) Abstract The Basilica Julii (also known as titulus Callisti and later as Santa Maria in Trastevere) provides a case study of the physical and social conditions in which early Christian liturgies ‘rewired’ their participants. This paper demon- strates that liturgical transformation was a two-way process, in which liturgy was the object as well as the agent of change. Three essential factors – the liturgy of the Eucharist, the space of the early Christian basilica, and the local Christian community – are described as they existed in Rome from the fourth through the ninth centuries. The essay then takes up the specific case of the Basilica Julii, showing how these three factors interacted in the con- crete conditions of a particular titular church. The basilica’s early Christian liturgical layout endured until the ninth century, when it was reconfigured by Pope Gregory IV (827-844) to bring the liturgical sub-spaces up-to- date. In Pope Gregory’s remodeling the original non-hierarchical layout was replaced by one in which celebrants were elevated above the congregation, women were segregated from men, and higher-ranking lay people were accorded places of honor distinct from those of lesser stature. These alterations brought the Basilica Julii in line with the requirements of the ninth-century papal stational liturgy. The stational liturgy was hierarchically orga- nized from the beginning, but distinctions became sharper in the course of the early Middle Ages in accordance with the expansion of papal authority and changes in lay society. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

Diversity in Death; Differences in Burial Ritual As Recorded in Central Italy, 950-500 BC

University of Groningen Diversity in Death Nijboer, Albert J. Published in: The Archaeology of Death IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Nijboer, A. J. (2018). Diversity in Death: a construction of identities and the funerary record of multi-ethnic central Italy from 950-350 BC. In E. Herring, & E. O'Donoghue (Eds.), The Archaeology of Death: Proceedings of the Seventh Conference of Italian Archaeology held at the National University of Ireland, Galway, April 16-18, 2016 (Vol. VI, pp. 107-127). [14] (Papers in Italian Archaeology VII ). Archaeopress. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal.