University of Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur Rural District from 30.08.2020To05.09.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur Rural district from 30.08.2020to05.09.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KOLLAMPARAMBI PRADEEPAN L HOUSE 30-08-2020 841/2020 ALOOR .T.N APPUKUTT 39, VELLANCHI BAILED BY 1 SANTHOSH THURUTHIPARAM at 21:05 U/s 117(e) (Thrissur SI OF AN Male RA POLICE BU DESAM Hrs KP Act Rural) POLICE ALOOR VILLAGE (GRADE ) PRADEEPAN THEETHAI 30-08-2020 841/2020 ALOOR .T.N 36, HOUSE VELLANCHI BAILED BY 2 LINESH THOMAS at 21:05 U/s 117(e) (Thrissur SI OF Male THIRUTHIPARAM RA POLICE Hrs KP Act Rural) POLICE BU DESAM ALOOR (GRADE ) 830/2020 U/s 188, 269, KALAPPURAKKAL KAIPAMAN 30-08-2020 270 IPC, JITHU @ BAGHEERA 25, (H) PONMANIK GALAM K.S.SUBINTH BAILED BY 3 at 21:35 4(2)(a) r/w 5 APPU THAN Male PONMANIKKUDA UDAM (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE Hrs KEDO M , PERINJANAM, Rural) &15(C) OF ABKARI ACT 830/2020 U/s 188, 269, KAIPAMAN KOTTAYI HOUSE 30-08-2020 270 IPC, 22, PONMANIK GALAM K.S.SUBINTH BAILED BY 4 ANDREWS DAVID PONMANIKUDAM at 21:35 4(2)(a) r/w 5 Male UDAM (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE (D),PERINJANAM Hrs KEDO Rural) &15(C) OF ABKARI ACT 830/2020 U/s 188, 269, KALAPURAKKAL KAIPAMAN 30-08-2020 270 IPC, SANIL 23, (H) PONMANIK GALAM K.S.SUBINTH BAILED BY 5 ANANDU at 21:35 4(2)(a) r/w 5 KUMAR Male PONMANIKUDAM UDAM (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE Hrs KEDO , PERINJANAM, Rural) &15(C) OF ABKARI ACT 830/2020 U/s 188, 269, KAIPAMAN ERATTU HOUSE 30-08-2020 270 IPC, 23, PONMANIK GALAM K.S.SUBINTH BAILED BY 6 PRAJEESH PRADEEP ,CHAKKARAPADA at 21:35 4(2)(a) r/w 5 Male UDAM (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE M PERINJANAM Hrs KEDO Rural) &15(C) OF ABKARI ACT 1514/2020 30-08-2020 VALAPPAD ARISTOTTIL. -

Panchayat Resource Mapping to Panchayat-Level Planning in Kerala: an Analytical Study

Panchayat Resource Mapping to Panchayat-level Planning in Kerala: An Analytical Study Srikumar Chattopadhyay, P. Krishna Kumar & K. Rajalekshmi Discussion Paper No. 14 December 1999 Kerala Research Programme for Local Level Development Centre for Development Studies Thiruvananthapuram Panchayat Resource Mapping to Panchayat-level Planning in Kerala: An Analytical Study Srikumar Chattopadhyay, P. Krishna Kumar & K. Rajalekshmi English Discussion Paper Rights reserved First published December 1999 Copy Editing: H. Shaji Printed at: Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development Published by: Dr K. N. Nair, Programme Co-ordinator, Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development, Centre for Development Studies, Prasanth Nagar, Ulloor, Thiruvananthapuram 695 011 Tel: 550 465, 550 491 Fax: 550 465 E-mail: [email protected] Url: http://www.krpcds.org/ Cover Design: Defacto Creations ISBN No: 81-87621-13-3 Price: in India Rs 40 outside India US$5 KRPLLD 12/1999 0750 ENG 2 Panchayat Resource Mapping to Panchayat-level Planning in Kerala: An Analytical Study Srikumar Chattopadhyay, P. Krishna Kumar & K. Rajalekshmi * 1. Introduction Background Considerable emphasis has gone into decentralisation and micro-level planning with peoples initiative and participation in the process of development since introduction of the Eighth Five-Year Plan. The 72nd and the 73rd Constitutional amendment bills of 1991 provided Constitutional safeguards towards the establishment of Panchayati Raj Institutions at the district, block, and panchayat levels. The panchayats are supposed to be empowered with respect to: (i) Preparation of plans for economic development and social justice; and (ii) Implementation of schemes for economic development and social justice as may be entrusted to them including those in relation to matters listed in the 11th Schedule of the Constitution. -

List of Teachers Posted from the Following Schools to Various Examination Centers As Assistant Superintendents for Higher Secondary Exam March 2015

LIST OF TEACHERS POSTED FROM THE FOLLOWING SCHOOLS TO VARIOUS EXAMINATION CENTERS AS ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENTS FOR HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM MARCH 2015 08001 - GOVT SMT HSS,CHELAKKARA,THRISSUR 1 DILEEP KUMAR P V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04884231495, 9495222963 2 SWAPNA P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9846374117 3 SHAHINA.K 08035-GOVT. RSR VHSS, VELUR, THRISSUR 04885241085, 9447751409 4 SEENA M 08041-GOVT HSS,PAZHAYANNOOR,THRISSUR 04884254389, 9447674312 5 SEENA P.R 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872356188, 9947088692 6 BINDHU C 08062-ST ANTONY S HSS,PUDUKAD,THRISSUR 04842331819, 9961991555 7 SINDHU K 08137-GOVT. MODEL HSS FOR GIRLS, THRISSUR TOWN, , 9037873800 THRISSUR 8 SREEDEVI.S 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9020409594 9 RADHIKA.R 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742552608, 9847122431 10 VINOD P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9446146634 11 LATHIKADEVI L A 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742482838, 9048923857 12 REJEESH KUMAR.V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04762831245, 9447986101 08002 - GOVT HSS,CHERPU,THRISSUR 1 PREETHY M K 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR 04802820505, 9496288495 2 RADHIKA C S 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR , 9495853650 3 THRESSIA A.O 08005-GOVT HSS,KODAKARA,THRISSUR 04802726280, 9048784499 4 SMITHA M.K 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872317979, 8547619054 5 RADHA M.R 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872342425, 9497180518 6 JANITHA K 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872448686, 9744670871 1 7 SREELEKHA.E.S 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872343515, 9446541276 8 APINDAS T T 08095-ST. PAULS CONVENT EHSS KURIACHIRA, THRISSUR, 04872342644, 9446627146 680006 9 M.JAMILA BEEVI 08107-SN GHSS, KANIMANGALAM, THRISSUR, 680027 , 9388553667 10 MANJULA V R 08118-TECHNICAL HSS, VARADIAM, THRISSUR, 680547 04872216227, 9446417919 11 BETSY C V 08138-GOVT. -

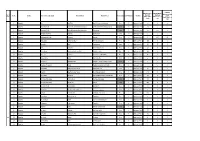

LUNCH LUNCH Sl

LUNCH LUNCH Sl. No Of LUNCH Home Sponsored District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Rural / Urban Initiative Contact No No. Members (July 23) Delivery by LSGI's (July 23) (July 23) 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 89 0 9544149437 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Coir Machine Manufacturing Company Urban 4 Janakeeya Hotel 0 110 34 8606334340 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Community kitchen thavakkal group MCH junction Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 6238772189 4 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashala Pazhaveedu Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 629 0 9745746427 5 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha North Swaruma Neerkkunnam Rural 10 Janakeeya Hotel 0 153 0 9656113003 6 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha North Annam janakeeya bhakshanashala Vandanam Rural 7 Janakeeya Hotel 0 62 0 919656146204 7 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 284 6 9061444582 8 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 Janakeeya Hotel 0 117 0 9961423245 9 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Poompatta catering and Bakery Unit Valiya azheekal, Aratpuzha Rural 3 Janakeeya Hotel 0 100 0 9544122586 10 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Snehadeepam Janakeeya Hotel Arattupuzha Rural 3 Janakeeya Hotel 0 45 0 8943892798 11 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 8921361281 12 Alappuzha Aroor Navaruchi Vyasa charitable trust Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 9562320377 13 Alappuzha Aryad Anagha Catering Near Aryad Panchayat Rural 5 Janakeeya -

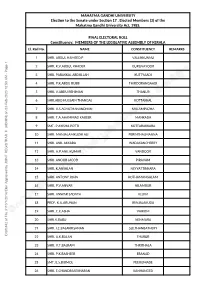

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY Election to The

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY Election to the Senate under Section 17 , Elected Members (3) of the Mahatma Gandhi University Act, 1985. FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL Constituency: MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF KERALA El. Roll No. NAME CONSTITUENCY REMARKS 1 SHRI. ABDUL HAMEED.P VALLIKKUNNU 2 SHRI. K.V.ABDUL KHADER GURUVAYOOR 3 SHRI. PARAKKAL ABDULLAH KUTTYAADI 4 SHRI. P.K.ABDU RUBB THIROORANGAADI 5 SHRI. V.ABDU REHIMAN THANUR 6 SHRI.ABID HUSSAIN THANGAL KOTTAKKAL 7 SHRI. V.S ACHUTHANANDHAN MALAMPUZHA 8 SHRI. T.A.AHAMMAD KABEER MANKADA 9 SMT. P AYISHA POTTI KOTTARAKKARA 10 SHRI. MANJALAMKUZHI ALI PERINTHALMANNA 11 SHRI. ANIL AKKARA WADAKANCHERRY 12 SHRI. A.P.ANIL KUMAR VANDOOR 13 SHRI. ANOOB JACOB PIRAVAM 14 SHRI. K.ANSALAN NEYYATTINKARA 15 SHRI. ANTONY JOHN KOTHAMANGALAM 16 SHRI. P.V.ANVAR NILAMBUR 17 SHRI. ANWAR SADATH ALUVA 18 PROF. K.U.ARUNAN IRINJALAKUDA 19 SHRI. C.K.ASHA VAIKOM 20 SHRI.K.BABU NENMARA 21 SHRI. I.C.BALAKRISHNAN SULTHANBATHERY Draft #42 of File 3110/1/2014/Elen Approved by JOINT REGISTRAR II (ADMIN) on 03-Feb-2020 10:50 AM - Page 1 22 SHRI. A.K.BALAN THARUR 23 SHRI. V.T.BALRAM THRITHALA 24 SHRI. P.K.BASHEER ERANAD 25 SMT. E.S.BIJIMOL PEERUMADE 26 SHRI. E.CHANDRASEKHARAN KANHANGED 27 SHRI. K.DASAN QUILANDY 28 SHRI. B.D DEVASSY CHALAKUDI 29 SHRI. C.DIVAKARAN NEDUMANGAD 30 SHRI. V.K.IBRAHIM KUNJU KALAMASSERY 31 SHRI. ELDO ABRAHAM MUVATTUPUZHA 32 SHRI. ELDOSE P KANNAPPILLIL PERUMBAVOOR 33 SHRI. K.B.GANESH KUMAR PATHANAPURAM 34 SMT. GEETHA GOPI NATTIKA 35 SHRI. GEORGE M THOMAS THIRUVAMBADI 36 SHRI. -

Janakeeya Hotel Updation 02.11.2020

LUNCH LUNCH Parcel LUNCH Home Sponsored by No. of By Unit Delivery Sl. No. District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Rural / Urban No Of Members Initiative LSGI's units (November (November 2 (November 2 2nd) nd) nd) 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Coir Machine Manufacturing Company Urban 4 Janakeeya Hotel 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashala Pazhaveedu Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 4 Alappuzha Ambalppuzha North Swaruma Neerkkunnam Rural 10 Janakeeya Hotel 5 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 6 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 Janakeeya Hotel 7 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 8 Alappuzha Aroor Navaruchi Vyasa charitable trust Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 9 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal chantha Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 10 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 11 Alappuzha Chambakulam Jyothis Near party office Rural 4 Janakeeya Hotel 12 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM chengannur market building complex Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 13 Alappuzha Chennam Pallippuram Friends Chennam pallipuram panchayath Rural 3 Janakeeya Hotel 14 Alappuzha Chennithala Bhakshana sree canteen Chennithala Town Rural 4 Janakeeya Hotel 15 Alappuzha Cheppad Sreebhadra catering unit Choondupalaka junction Rural 3 Janakeeya Hotel 16 Alappuzha Cheriyanad DARSANA Near -

Covid-19 Outbreak Control and Prevention State Cell Health & Family

COVID-19 OUTBREAK CONTROL AND PREVENTION STATE CELL HEALTH & FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT GOVT. OF KERALA www.health.kerala.gov.in www.dhs.kerala.gov.in [email protected] Date: 06/05/2021 Time: 02:00 PM The daily COVID-19 bulletin of the Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Kerala summarizes the COVID-19 situation in Kerala. The details of hotspots identified are provided in Annexure-1 for quick reference. The bulletin also contains links to various important documents, guidelines, and websites for references. OUR HEALTH OUR RESPONSIBILITY • Maintain a distance of at least two metres with all people all the time. • Always wear clean face mask appropriately everywhere all the time • Perform hand hygiene after touching objects and surfaces all the time. • Perform hand hygiene before and after touching your face. • Observe cough and sneeze hygiene always • Stay Home; avoid direct social interaction and avoid travel • Protect the elderly and the vulnerable- Observe reverse quarantine • Do not neglect even mild symptoms; seek health care “OUR HEALTH OUR RESPONSIBILITY” Page 1 of 25 PART- 1 SUMMARY OF COVID CASES AND DEATH Table 1. Summary of COVID-19 cases till 05/05/2021 New persons New Persons New persons Positive Recovered added to added to Home, in Hospital Deaths cases patients Quarantine/ Institution Isolation Isolation quarantine 1743932 1362363 56385 52517 3868 5565 Table 2. Summary of new COVID-19 cases (last 24 hours) New Persons New persons added to New persons Positive Recovered added to Home, in Hospital Deaths cases patients Quarantine/ Institution Isolation Isolation quarantine 42464 27152 65266 61633 3633 63 Table 3. -

Ecology of Wetland Birds in the Kole Lands of Kerala

KFRI Research Report No. 244 ISSN 0970-8103 ECOLOGY OF WETLAND BIRDS IN THE KOLE LANDS OF KERALA E. A. Jayson Kerala Forest Research Institute Peechi- 680 653, Kerala, India October 2002 KFRI Research Report No. 244 ECOLOGY OF WETLAND BIRDS IN THE KOLE LANDS OF KERALA (FINAL REPORT OF THE RESEARCH PROJECT KFRI/303/98) E. A. Jayson Division of Wildlife Biology Kerala Forest Research Institute Peechi- 680 653, Kerala, India October 2002 1. INTRODUCTION Wetlands are complex ecosystems with many interacting organisms. Wetlands are defined as areas of marsh, ponds, swamps, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including that of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six meters (IUCN, 1971). Wetlands are extremely important throughout the world for wildlife protection, recreation, pollution and sediment control, flood prevention and food production. Cowardin et al. (1979) define wetlands as ‘the lands transitional between terrestrial and aquatic system where the water table is usually at or near the surface or the land is covered by shallow water. Wetlands must have one or more of the three attributes: 1) at least periodically, the land supports predominantly hydrophytes, 2) the substrate is predominantly undrained hydric soil and 3) the substrate is nonsoil and is saturated with water or covered by shallow water at some time during the growing season of each year. Although considerable amount of research on wetlands has been done in India, most of the information has come from Keoladio, Point Calimere, Chilka Lake and the Sunderbans or from specific regions such as Gujarat and Ladakh (Wolstencroft et al., 1989). -

Report of Rapid Impact Assessment of Flood/ Landslides on Biodiversity Focus on Community Perspectives of the Affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems

IMPACT OF FLOOD/ LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVES AUGUST 2018 KERALA state BIODIVERSITY board 1 IMPACT OF FLOOD/LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY - COMMUnity Perspectives August 2018 Editor in Chief Dr S.C. Joshi IFS (Retd) Chairman, Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram Editorial team Dr. V. Balakrishnan Member Secretary, Kerala State Biodiversity Board Dr. Preetha N. Mrs. Mithrambika N. B. Dr. Baiju Lal B. Dr .Pradeep S. Dr . Suresh T. Mrs. Sunitha Menon Typography : Mrs. Ajmi U.R. Design: Shinelal Published by Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram 2 FOREWORD Kerala is the only state in India where Biodiversity Management Committees (BMC) has been constituted in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporation way back in 2012. The BMCs of Kerala has also been declared as Environmental watch groups by the Government of Kerala vide GO No 04/13/Envt dated 13.05.2013. In Kerala after the devastating natural disasters of August 2018 Post Disaster Needs Assessment ( PDNA) has been conducted officially by international organizations. The present report of Rapid Impact Assessment of flood/ landslides on Biodiversity focus on community perspectives of the affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems. It is for the first time in India that such an assessment of impact of natural disasters on Biodiversity was conducted at LSG level and it is a collaborative effort of BMC and Kerala State Biodiversity Board (KSBB). More importantly each of the 187 BMCs who were involved had also outlined the major causes for such an impact as perceived by them and suggested strategies for biodiversity conservation at local level. Being a study conducted by local community all efforts has been made to incorporate practical approaches for prioritizing areas for biodiversity conservation which can be implemented at local level. -

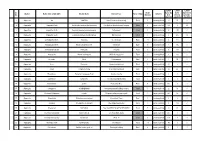

Sl. No. District Name of the LSGD (CDS)

LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Sl. No Of Parcel By Home Sponsored District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Rural / Urban Initiative No. Members Unit Delivery by LSGI's (April 23) (April 23) (April 23) 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 10 65 0 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Coir Machine Manufacturing Company Urban 4 Janakeeya Hotel 122 0 20 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashal Pazhaveedu Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 80 155 0 4 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Community kitchen thavakkal group MCH junction Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 355 12 5 Alappuzha Ambalppuzha North Swaruma Neerkkunnam Rural 10 Janakeeya Hotel 0 100 2 6 Alappuzha Ambalppuzha North Annam Janakeeya Hotel Vandanam Rural 7 Janakeeya Hotel 0 152 0 7 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 166 6 8 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 Janakeeya Hotel 8 132 0 9 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 7 96 0 10 Alappuzha Aroor Navaruchi Vyasa charitable trust Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 40 0 0 11 Alappuzha Aryad Anagha Catering Near Aryad Panchayat Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 74 40 0 12 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal chantha Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 13 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 14 Alappuzha Chambakulam Jyothis Near party office Rural 4 Janakeeya Hotel 193 0 0 15 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM chengannur market building -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur Rural District from 11.02.2018 to 17.02.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur Rural district from 11.02.2018 to 17.02.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 AINIKKAL HOUSE, 11.02.201 CR.141/18 52/18 PERINGOTTU S.R.SANEESH. JFCM NO II 1 MOHANAN AYYAPPAN KIZHUPPILLIKKARA 8 AT 16.50 U/S 15 OF KG ANTHIKAD MALE KKARA SI OF POLICE THRISSUR THRISSUR HRS ACT 11.02.201 CR.141/18 28/18 NJATTUVETTY PERINGOTTU S.R.SANEESH. JFCM NO II 2 KIRAN DASAN 8 AT 16.50 U/S 15 OF KG ANTHIKAD MALE HOUSE THRISSUR KKARA SI OF POLICE THRISSUR HRS ACT KARTTUPARAMBIL HOUSE, 11.02.201 CR.141/18 SANKARA 40/18 PERINGOTTU S.R.SANEESH. JFCM NO II 3 SUDHIR K S KIZHUPPILLIKKARA, 8 AT 16.50 U/S 15 OF KG ANTHIKAD NARAYANAN MALE KKARA SI OF POLICE THRISSUR THANNYAM HRS ACT THRISSUR CR.142/18 VALLANGAPARAMBI 11.02.201 53/18 U/S 15 (C ) S.R.SANEESH. JFCM NO II 4 SAHADEVAN AYYAPPAN L HOUSE, MANALUR MANALOOR 8 AT 17.20 ANTHIKAD MALE R/W 63 OF SI OF POLICE THRISSUR THRISSUR HRS ABAKARI ACT CR.142/18 ELVALLY HOUSE, 11.02.201 43/18 U/S 15 (C ) S.R.SANEESH. JFCM NO II 5 BABU KOCHUMON MANALUR MANALOOR 8 AT 17.20 ANTHIKAD MALE R/W 63 OF SI OF POLICE THRISSUR THRISSUR HRS ABAKARI ACT CR.143/18 ORIPARAMBIL 11.02.201 36/18 U/S 15 (C ) S.R.SANEESH. -

Mgl- Int 4-2015 Unpai D Shareholders List As on 31

FOLIO-DEMAT ID NAME NETDIV DWNO MICR DDNO ADDRESS1 ADDRESS2 ADDRESS3 ADDRESS4 CITY PINCOD JH1 JH2 001221 DWARKA NATH ACHARYA 180000.00 15400038 375366 5 JAG BANDHU BORAL LANE CALCUTTA 700007 002855 VIJAYAN M 17136.00 15400044 582053 MELATHIL HOUSE PO WADAKKANCHERRY KARTHIAYANI M N 000000 001431 JITENDRA DATTA MISRA 10800.00 15400048 582057 BHRATI AJAY TENAMENTS 5 VASTRAL RAOD WADODHAV PO AHMEDABAD 382415 001424 BALARAMAN S N 18000.00 15400053 582062 14 ESOOF LUBBAI ST TRIPLICANE MADRAS 600005 001209 PANCHIKKAL NARAYANAN 18000.00 15400057 582066 NANU BHAVAN KACHERIPARA KANNUR KERALA 670009 001440 RAJI GOPALAN 18000.00 15400064 582073 ANASWARA KUTTIPURAM THIROOR ROAD KUTTYPURAM KERALA 679571 IN30051313904028 AYYAPPAN V 18000.00 15400124 144219 SRI RAMA NIVAS P O VALAPAD THRISSUR KERALA 680567 000050 HAJI M.M.ABDUL MAJEED 18000.00 15400148 582157 MUKRIAKATH HOUSE VATANAPALLY TRICHUR DIST. KERALA 680614 001237 MENON C B 18000.00 15400174 582183 PANAMPILLY HOUSE ANNAMANABI THRISSUR KERALA 680741 000642 JNANAPRAKASH P.S. 1800.00 15400197 582206 POZHEKKADAVIL HOUSE P.O.KARAYAVATTAM TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 68056 MRS. LATHA M.V. 000691 BHARGAVI V.R. 1800.00 15400199 582208 C/O K.C.VISHWAMBARAN,P.B.NO.63 ADV.KAYCEE & KAYCEE AYYANTHOLE TRICHUR DISTRICT KERALA STATE 000902 SREENIVAS M.V. 1800.00 15400205 582214 SAI SREE, KOORKKENCHERY TRICHUR - 7 KERALA STATE MRS. RAJALAKSHMI SREENIVAS 001036 SANKAR T.C. 9000.00 15400210 582219 DAYA MANDIRAM TRICHUR - 4. KERALA MRS. MADHAVIKUTTY T.A. 002562 SHEBY FRANCIS 1800.00 15400222 582231 S/O M A FRANCIS MAROCKY HOUSE NEAR HOSPITAL ROAD P O CHAVAKKAD 772626 DAMODARAN NAMBOODIRI K T 3600.00 15400228 582237 KANJIYIL THAMARAPPILLY MANA P O MANALOOR THRISSUR KERALA 002679 NARAYANAN P S 3600.00 15400231 582240 PANAT HOUSE P O KARAYAVATTOM, VALAPAD THRISSUR KERALA 002768 SANTHA JOHN.MRS.