Obstetric Care in Low-Resource Settings: What, Who, and How to Overcome Challenges to Scale Up?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delivery Mode for Prolonged, Obstructed Labour Resulting in Obstetric Fistula: a Etrr Ospective Review of 4396 Women in East and Central Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eCommons@AKU eCommons@AKU Obstetrics and Gynaecology, East Africa Medical College, East Africa 12-17-2019 Delivery mode for prolonged, obstructed labour resulting in obstetric fistula: a etrr ospective review of 4396 women in East and Central Africa C. J. Ngongo T. J. Raassen L. Lombard J van Roosmalen S. Weyers See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/eastafrica_fhs_mc_obstet_gynaecol Part of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons Authors C. J. Ngongo, T. J. Raassen, L. Lombard, J van Roosmalen, S. Weyers, and Marleen Temmerman DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.16047 www.bjog.org Delivery mode for prolonged, obstructed labour resulting in obstetric fistula: a retrospective review of 4396 women in East and Central Africa CJ Ngongo,a TJIP Raassen,b L Lombard,c J van Roosmalen,d,e S Weyers,f M Temmermang,h a RTI International, Seattle, WA, USA b Nairobi, Kenya c Cape Town, South Africa d Athena Institute VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands e Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands f Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium g Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health, Aga Khan University, Nairobi, Kenya h Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium Correspondence: CJ Ngongo, RTI International, 119 S Main Street, Suite 220, Seattle, WA 98104, USA. Email: [email protected] Accepted 3 December 2019. Objective To evaluate the mode of delivery and stillbirth rates increase occurred at the expense of assisted vaginal delivery over time among women with obstetric fistula. -

A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of This Document Is Made Possible by Financial Contributions from Health Canada and Provincial and Territorial Governments

ICD-10-CA | CCI A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of this document is made possible by financial contributions from Health Canada and provincial and territorial governments. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada or any provincial or territorial government. Unless otherwise indicated, this product uses data provided by Canada’s provinces and territories. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be reproduced unaltered, in whole or in part and by any means, solely for non-commercial purposes, provided that the Canadian Institute for Health Information is properly and fully acknowledged as the copyright owner. Any reproduction or use of this publication or its contents for any commercial purpose requires the prior written authorization of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Reproduction or use that suggests endorsement by, or affiliation with, the Canadian Institute for Health Information is prohibited. For permission or information, please contact CIHI: Canadian Institute for Health Information 495 Richmond Road, Suite 600 Ottawa, Ontario K2A 4H6 Phone: 613-241-7860 Fax: 613-241-8120 www.cihi.ca [email protected] © 2018 Canadian Institute for Health Information Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre Guide de codification des données en obstétrique. Table of contents About CIHI ................................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. -

THE PRACTICE of EPISIOTOMY: a QUALITATIVE DESCRIPTIVE STUDY on PERCEPTIONS of a GROUP of WOMEN Online Brazilian Journal of Nursing, Vol

Online Brazilian Journal of Nursing E-ISSN: 1676-4285 [email protected] Universidade Federal Fluminense Brasil Yi Wey, Chang; Rejane Salim, Natália; Pires de Oliveira Santos Junior, Hudson; Gualda, Dulce Maria Rosa THE PRACTICE OF EPISIOTOMY: A QUALITATIVE DESCRIPTIVE STUDY ON PERCEPTIONS OF A GROUP OF WOMEN Online Brazilian Journal of Nursing, vol. 10, núm. 2, abril-agosto, 2011, pp. 1-11 Universidade Federal Fluminense Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=361441674008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative THE PRACTICE OF EPISIOTOMY: A QUALITATIVE DESCRIPTIVE STUDY ON PERCEPTIONS OF A GROUP OF WOMEN Chang Yi Wey1, Natália Rejane Salim2, Hudson Pires de Oliveira Santos Junior3, Dulce Maria Rosa Gualda4 1. Hospital Universitário, Universidade de São Paulo 2,3,4. Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade de São Paulo ABSTRACT: This study set out to understand the experiences and perceptions of women from the practices of episiotomy during labor. This is a qualitative descriptive approach, performed in a school hospital in São Paulo, which data were collected through interviews with the participation of 35 women, who experienced and not episiotomy in labor. The thematic analysis shows these categories: Depends the size of the baby facilitates the childbirth; Depends each woman; The woman is not open; and Episiotomy is not necessary. The results allowed that there is lack of clarification and knowledge regarding this practice, which makes the role of decision ends up in the professionals’ hands. -

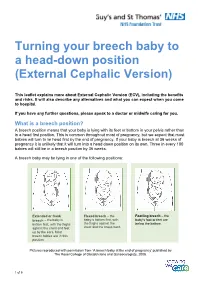

Turning Your Breech Baby to a Head-Down Position (External Cephalic Version)

Turning your breech baby to a head-down position (External Cephalic Version) This leaflet explains more about External Cephalic Version (ECV), including the benefits and risks. It will also describe any alternatives and what you can expect when you come to hospital. If you have any further questions, please speak to a doctor or midwife caring for you. What is a breech position? A breech position means that your baby is lying with its feet or bottom in your pelvis rather than in a head first position. This is common throughout most of pregnancy, but we expect that most babies will turn to lie head first by the end of pregnancy. If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy it is unlikely that it will turn into a head down position on its own. Three in every 100 babies will still be in a breech position by 36 weeks. A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions: Extended or frank Flexed breech – the Footling breech – the breech – the baby is baby is bottom first, with baby’s foot or feet are bottom first, with the thighs the thighs against the below the bottom. against the chest and feet chest and the knees bent. up by the ears. Most breech babies are in this position. Pictures reproduced with permission from ‘A breech baby at the end of pregnancy’ published by The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2008. 1 of 5 What causes breech? Breech is more common in women who are expecting twins, or in women who have a differently-shaped womb (uterus). -

Gtg-No-20B-Breech-Presentation.Pdf

Guideline No. 20b December 2006 THE MANAGEMENT OF BREECH PRESENTATION This is the third edition of the guideline originally published in 1999 and revised in 2001 under the same title. 1. Purpose and scope The aim of this guideline is to provide up-to-date information on methods of delivery for women with breech presentation. The scope is confined to decision making regarding the route of delivery and choice of various techniques used during delivery. It does not include antenatal or postnatal care. External cephalic version is the topic of a separate RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 20a: ECV and Reducing the Incidence of Breech Presentation. 2. Background The incidence of breech presentation decreases from about 20% at 28 weeks of gestation to 3–4% at term, as most babies turn spontaneously to the cephalic presentation. This appears to be an active process whereby a normally formed and active baby adopts the position of ‘best fit’ in a normal intrauterine space. Persistent breech presentation may be associated with abnormalities of the baby, the amniotic fluid volume, the placental localisation or the uterus. It may be due to an otherwise insignificant factor such as cornual placental position or it may apparently be due to chance. There is higher perinatal mortality and morbidity with breech than cephalic presentation, due principally to prematurity, congenital malformations and birth asphyxia or trauma.1,2 Caesarean section for breech presentation has been suggested as a way of reducing the associated perinatal problems2,3 and in many countries in Northern Europe and North America caesarean section has become the normal mode of breech delivery. -

Clinical and Physical Aspects of Obstetric Vacuum Extraction

CLINICAL AND PHYSICAL ASPECTS OF OBSTETRIC VACUUM EXTRACTION KLINISCHE EN FYSISCHE ASPECTEN VAN OnSTETRISCHE VACUUM EXTRACTIE Clinical and physical aspects of obstetric vacuum extraction I Jette A. Kuit Thesis Rotterdam - with ref. - with summary in Dutch ISBN 90-9010352-X Keywords Obstetric vacuum extraction, oblique traction, rigid cup, pliable cup, fetal complications, neonatal retinal hemorrhage, forceps delivery Copyright Jette A. Kuit, Rotterdam, 1997. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the holder of the copyright. Cover, and drawings in the thesis, by the author. CLINICAL AND PHYSICAL ASPECTS OF OBSTETRIC VACUUM EXTRACTION KLINISCHE EN FYSISCHE ASPECTEN VAN OBSTETRISCHE VACUUM EXTRACTIE PROEFSCHRIFf TER VERKRUGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR AAN DE ERASMUS UNIVERSITEIT ROTTERDAM OP GEZAG VAN DE RECTOR MAGNIFICUS PROF. DR. P.W.C. AKKERMANS M.A. EN VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VOOR PROMOTIES DE OPENBARE VERDEDIGING ZAL PLAATSVINDEN OP WOENSDAG 2 APRIL 1997 OM 15.45 UUR DOOR JETTE ALBERT KUIT GEBOREN TE APELDOORN Promotiecommissie Promotor Prof.dr. H.C.S. Wallenburg Overige leden Prof.dr. A.C. Drogendijk Prof. dr. G.G.M. Essed Prof.dr.ir. C.l. Snijders Co-promotor Dr. F.J.M. Huikeshoven To my parents, to Irma, Suze and Julius. CONTENTS 1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION 9 2. VACUUM CUPS AND VACUUM EXTRACTION; A REVIEW 13 2.1. Introduction 2.2. Obstetric vacuum cups in past and present 2.2.1. Historical backgroulld 2.2.2. -

Three Typical Claims in Shoulder Dystocia Lawsuits

Three Typical Claims in Shoulder Dystocia Lawsuits Henry Lerner, MD Dr. Lerner practices obstetrics and gynecology at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Massachusetts. t the end of a busy day, your office manager comes in The plaintiff’s lawyer and expert witnesses willclaim that it was holding a thick envelope. You don’t like the look on the physician’s duty to assess whether the baby was at increased her face. As she hands it to you, you see the return risk for shoulder dystocia at delivery. Plaintiffs will enumerate a Aaddress is a law firm. The envelope holds a summons indicating series of factors gleaned from their history and medical records that a malpractice lawsuit is being filed against you. The name which they will claim indicate that they were at increased risk of the patient involved seems only vaguely familiar. When for shoulder dystocia. Such factors include: you review the chart, you see that it was a delivery with a mild Prelabor risks (alleged): shoulder dystocia—four years ago. ■■ Suspected big baby As an obstetrician who has been in practice for more than 28 ■■ Gestational diabetes years, had numerous shoulder dystocia deliveries, and reviewed ■■ Large maternal weight gain close to 100 shoulder dystocia medical-legal cases, I have seen ■■ Large uteri fundal height measurement the above scenario played out frequently. In some cases, the ■■ Small pelvis delivery was catastrophic and the obstetrician was unsurprised ■■ Small maternal stature by the lawsuit. In most cases, however, the delivery was just ■■ Previous large baby one of hundreds or thousands the doctor has done over the ■■ Known male fetus years…and forgotten. -

Mid-Trimester Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes (PPROM): Etiology, Diagnosis, Classification, International Recommendations of Treatment Options and Outcome

J. Perinat. Med. 2018; 46(5): 465–488 Review article Open Access Michael Tchirikov*, Natalia Schlabritz-Loutsevitch, James Maher, Jörg Buchmann, Yuri Naberezhnev, Andreas S. Winarno and Gregor Seliger Mid-trimester preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM): etiology, diagnosis, classification, international recommendations of treatment options and outcome DOI 10.1515/jpm-2017-0027 neonates delivered without antecedent PPROM. The “high Received January 23, 2017. Accepted May 19, 2017. Previously pub- PPROM” syndrome is defined as a defect of the chorio- lished online July 15, 2017. amniotic membranes, which is not located over the inter- nal cervical os. It may be associated with either a normal Abstract: Mid-trimester preterm premature rupture of mem- or reduced amount of amniotic fluid. It may explain why branes (PPROM), defined as rupture of fetal membranes sensitive biochemical tests such as the Amniosure (PAMG-1) prior to 28 weeks of gestation, complicates approximately or IGFBP-1/alpha fetoprotein test can have a positive result 0.4%–0.7% of all pregnancies. This condition is associ- without other signs of overt ROM such as fluid leakage with ated with a very high neonatal mortality rate as well as an Valsalva. The membrane defect following fetoscopy also increased risk of long- and short-term severe neonatal mor- fulfils the criteria for “high PPROM” syndrome. In some bidity. The causes of the mid-trimester PPROM are multi- cases, the rupture of only one membrane – either the cho- factorial. Altered membrane morphology including marked rionic or amniotic membrane, resulting in “pre-PPROM” swelling and disruption of the collagen network which is could precede “classic PPROM” or “high PPROM”. -

Chapter 12 Vaginal Breech Delivery

FOURTH EDITION OF THE ALARM INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM CHAPTER 12 VAGINAL BREECH DELIVERY Learning Objectives By the end of this chapter, the participant will: 1. List the selection criteria for an anticipated vaginal breech delivery. 2. Recall the appropriate steps and techniques for vaginal breech delivery. 3. Summarize the indications for and describe the procedure of external cephalic version (ECV). Definition When the buttocks or feet of the fetus enter the maternal pelvis before the head, the presentation is termed a breech presentation. Incidence Breech presentation affects 3% to 4% of all pregnant women reaching term; the earlier the gestation the higher the percentage of breech fetuses. Types of Breech Presentations Figure 1 - Frank breech Figure 2 - Complete breech Figure 3 - Footling breech In the frank breech, the legs may be extended against the trunk and the feet lying against the face. When the feet are alongside the buttocks in front of the abdomen, this is referred to as a complete breech. In the footling breech, one or both feet or knees may be prolapsed into the maternal vagina. Significance Breech presentation is associated with an increased frequency of perinatal mortality and morbidity due to prematurity, congenital anomalies (which occur in 6% of all breech presentations), and birth trauma and/or asphyxia. Vaginal Breech Delivery Chapter 12 – Page 1 FOURTH EDITION OF THE ALARM INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM External Cephalic Version External cephalic version (ECV) is a procedure in which a fetus is turned in utero by manipulation of the maternal abdomen from a non-cephalic to cephalic presentation. Diagnosis of non-vertex presentation Performing Leopold’s manoeuvres during each third trimester prenatal visit should enable the health care provider to make diagnosis in the majority of cases. -

Amnioinfusion in the Etiological Diagnosis and Therapeutics Of

14th World Congress in Fetal Medicine Amnioinfusion in the etiological diagnosis and therapeutics of oligohydramnios: 17 years of experience Borges-Costa S, Bernardo A, Santos A Prenatal Diagnosis Center, Hospital Garcia de Orta, Almada, Portugal Objective To review the maternal and fetal outcomes of all amnioinfusions performed for the diagnosis and treatment of oligohydramnios during pregnancy (excluding labor). Methods This is a retrospective study of 31 singleton pregnancies with oligohydramnios in the second and third trimesters which underwent transabdominal amnioinfusion between December/1997 and December/2014 in the Prenatal Diagnosis Center at the Hospital Garcia de Orta. The gestational age ranged from 15 weeks and 5 days to 32 weeks and 2 days (average 22 weeks). The initial amniotic fluid index ranged from 0 to 6, 5 cm. The procedure was done only by trained professionals. Under ultrasound guidance, isotonic fluid, such as normal saline or Ringer's lactate, is infused into the amniotic cavity via a 20 G needle inserted through the uterine wall. The volume infused ranged from 100 to 800cc (average 380cc). A genetic study was conducted in 29 cases (93, 5%), performed after amniocentesis (26 cases) or cordocentesis (3 cases). In all cases, there was an exhaustive study of the fetal anatomy after the amnioinfusion. In this study the following parameters were evaluated: maternal characteristics (age, personal and obstetrical history), evolution of pregnancy, perinatal mortality and maternal complications. Histopathological examinations -

Vaginal Breech Birth Mary Olusile Lecturer in Practice

1 Vaginal Breech birth Mary Olusile Lecturer in Practice Breech: is where the fetal buttocks is the presenting part. Occurs in 15% of pregnancies at 28wks reducing to 3-4% at term Usually associated with: Uterine & pelvic anomalies - bicornuate uterus, lax uterus, fibroids and cysts Fetal anomalies - anencephaly, hydrocephaly, multiple gestation, oligohydraminous and polyhydraminous Cornually placed placenta (probably the commonest cause). Diagnosis: by abdominal examination or vaginal examination and confirmed by ultrasound scan Vaginal Breech VS. Caesarean Section Trial by Hannah et al (2001) found CS to produce better outcomes than vaginal breech but does acknowledge that may be due to lost skills of operators Therefore recommended mode of delivery is CS Limitations of trial by Hannah et al have since been highlighted questioning results and conclusion (Kotaska 2004) Now some advocates for vaginal breech birth when selection is based on clear prelabour and intrapartum criteria (Alarab et al 2004) Breech birth is u sually not an option except at clients choice Important considerations are size of fetus, presentation, attitude, size of maternal pelvis and parity of the woman NICE recommendation: External cephalic version (ECV) to be considered and offered if appropriate Produced by CETL 2007 2 Vaginal Breech birth Anterior posterior diameter of the pelvic brim is 11 cm Oblique diameter of the pelvic brim is 12 cm Transverse diameter of the pelvic brim is 13 cm Anterior posterior diameter of the outlet is 13 cm Produced by CETL 2007 3 -

Shoulder Dystocia Abnormal Placentation Umbilical Cord

Obstetric Emergencies Shoulder Dystocia Abnormal Placentation Umbilical Cord Prolapse Uterine Rupture TOLAC Diabetic Ketoacidosis Valerie Huwe, RNC-OB, MS, CNS & Meghan Duck RNC-OB, MS, CNS UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Outreach Services, Mission Bay Objectives .Highlight abnormal conditions that contribute to the severity of obstetric emergencies .Describe how nurses can implement recommended protocols, procedures, and guidelines during an OB emergency aimed to reduce patient harm .Identify safe-guards within hospital systems aimed to provide safe obstetric care .Identify triggers during childbirth that increase a women’s risk for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Postpartum Depression . Incorporate a multidisciplinary plan of care to optimize care for women with postpartum emergencies Obstetric Emergencies • Shoulder Dystocia • Abnormal Placentation • Umbilical Cord Prolapse • Uterine Rupture • TOLAC • Diabetic Ketoacidosis Risk-benefit analysis Balancing 2 Principles 1. Maternal ‒ Benefit should outweigh risk 2. Fetal ‒ Optimal outcome Case Presentation . 36 yo Hispanic woman G4 P3 to L&D for IOL .IVF Pregnancy .3 Prior vaginal births: 7.12, 8.1, 8.5 (NCB) .Late to care – EDC ~ 40-41 weeks .GDM Type A2 – somewhat uncontrolled .4’11’’ .Hx of Lupus .BMI 40 .Gained ~ 40 lbs during pregnancy Question: What complication is she a risk for? a) Placental abruption b) Thyroid Storm c) Preeclampsia with severe features d) Shoulder dystocia e) Uterine prolapse Case Presentation . 36 yo Hispanic woman G4 P3 to L&D for IOL .IVF Pregnancy .3