Grace Hartigan and Helene Herzbrun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NMQF 2007 Leadership Summit Biographical Sketches

National Minority Quality Forum 2007 Leadership Summit Biographical Sketches Angel F. Avendano, MD Angel F. Avendano, MD, is a bilingual cardiologist with more than 20 years of clinical practice experience. He served as professor of medicine at Universidad Central de Venezuela. He cofounded and directed IDET, a main primary care institution in Venezuela. He has experience in clinical research since 1998 both international and in the United States. His work has been published. His research experience includes hypertension, hepatitis C, and HIV. His main research interests include the metabolic syndrome in HIV, lipid metabolic and cardiac risk factors in HIV, and hypertension. Jennifer Beaulieu (BIOGRAPHY NOT AVAILABLE.) Richard Beswick, PhD Richard Beswick, PhD, is associate medical director with Roche Laboratories Inc. Previously, Dr. Beswick served as manager of clinical affairs with Johnson and Johnson/Orthobiotech. During Dr. Beswick’s tenure with Orthobiotech, he was involved in new business development and clinical trial development. Born in Montego Bay, Jamaica, he earned a bachelor’s degree in biology from Morehouse College, Atlanta, GA, a master’s degree in cardiovascular physiology from Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant; a master’s in business administration from Rollins College in Florida; and a PhD in molecular renal physiology from the University of Michigan School of Medicine. Dr. Beswick trained with Janice Douglas and Jackson Wright at Case Western Reserve University in the area of endocrinology and receptor kinetics with a focus on angiotensin receptor system in the kidneys of African American patients. Moreover, he has been involved in and has developed numerous protocols for academia and pharmaceutical industry. -

Spanish Certificate Info and Sign up Form

International Certificate in Cultural Competency and Communication in Spanish One of the goals of Vision 2020 is to “diversify and globalize the A&M community”. Two key indicators in Texas A&M’s (TAMU) Quality Enhancement Plan are specific to creating excellence in diversity of student learning and in internationalization. These two goals are stated as follows: • Students graduating from Texas A&M University should be able to function successfully in complex, diverse, social, economic, and political contexts. • Students graduating from Texas A&M University will be able to function effectively in their chosen career fields in an international setting. Specifically, students who complete the BIMS International Certificate will: 1. Be functionally bilingual and employ attained language skills in both social and formal settings 2. Be able to perform linguistically and in a culturally sensitive manner within the medial and/or agricultural environment 3. Gain experiential knowledge abroad, expanding their cultural sensitivities and functionality in a foreign environment. Students should be able to compare and contrast Latin American and Spanish cultural ideas with those of the Anglo population within the United States. Students should recognize cultural differences, using language and social skills to interact effectively within a foreign environment. The certificate has been generated with the student’s required TAMU core curriculum in mind. Many students may wish to discuss a minor in language, political science, sociology, etc. based upon the courses taken to satisfy the certificate requirements. To discuss a minor, please speak with your academic advisor as well as the college/department in which you wish to minor. -

A Finding Aid to the Elaine De Kooning Papers, Circa 1959-1989, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Elaine de Kooning papers, circa 1959-1989, in the Archives of American Art Harriet E. Shapiro and Erin Kinhart 2015 October 21 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Personal Papers, circa 1960s-1989.......................................................... 4 Series 2: Interviews, Conversations, and Lectures, 1978-1988............................... 5 Series 3: Photographs, circa 1960s, 2013............................................................... 7 Series 4: Printed Material, 1961-1982.................................................................... -

2–22–05 Vol. 70 No. 34 Tuesday Feb. 22, 2005 Pages 8501–8708

2–22–05 Tuesday Vol. 70 No. 34 Feb. 22, 2005 Pages 8501–8708 VerDate jul 14 2003 20:36 Feb 18, 2005 Jkt 205001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\22FEWS.LOC 22FEWS i II Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 34 / Tuesday, February 22, 2005 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Ernest Briggs' Three Decades of Abstract Expressionist Painting

Ernest Briggs' Three Decades its help in allowing artists of the period to go to school. They were set of Abstract Expressionist Painting free economically, and were allowed to live comfortably with tuition and supplies paid for. The Fine Arts School would last about 3 years Ernest Briggs, a second generation Abstract Expressionist painter under McAgy. The program took off due to the presence of Clyfford known for his strong, lyrical, expressive brushstrokes, use of color and Still, Ad Reinhardt, along with David Park, Richard Diebenkorn, Elmer sometimes geometric composition, first came to New York in late 1953. Bischoff and others. Most of the students at the school, about 40-50 He had been a student of Clyfford Still at the California School of Fine taking painting, such luminaries as Dugmore, Hultberg, Schueler and Arts. Frank O’Hara first experienced the mystery in the way Ernest Crehan, had had some exposure to art through university or art school. Briggs’ splendid paintings transform, and the inability to see the shape But there had been no exposure to what was going on in New York or in as a shape apart from interpretation. Early in 1954, viewing Briggs’ first Europe in the art world, and Briggs and the others were little prepared one man show at the Stable Gallery in New York, O’Hara said in Art for the onslaught that was to come. in America “From the contrast between the surface bravura and the half-seen abstract shapes, a surprising intimacy arises which is like The California Years seeing a public statue, thinking itself unobserved, move.” With the entry of Still, the art program would “blow apart”. -

Summer 2021.Indd

Summer 2021 at | cmu.edu/osher w CONSIDER A GIFT TO OSHER To make a contribution to the Osher Annual Fund, please call the office at 412.268.7489, go through the Osher website with a credit card, or mail a check to the office. Thank you in advance for your generosity. BOARD OF DIRECTORS CURRICULUM COMMITTEE OFFICE STAFF Allan Hribar, President Stanley Winikoff (Curriculum Lyn Decker, Executive Director Jan Hawkins, Vice-President Committee Chair & SLSG) Olivia McCann, Administrator / Programs Marcia Taylor, Treasurer Gary Bates (Lecture Chair) Chelsea Prestia, Administrator / Publications Jim Reitz, Past President Les Berkowitz Kate Lehman, Administrator / General Office Ann Augustine, Secretary & John Brown Membership Chair Maureen Brown Mark Winer, Board Represtative to Flip Conti CATALOG EDITORS Executive Committee Lyn Decker (STSG) Chelsea Prestia, Editor Rosalie Barsotti Mary Duquin Jeffrey Holst Olivia McCann Anna Estop Kate Lehman Ann Isaac Marilyn Maiello Sankar Seetharama Enid Miller Raja Sooriamurthi Diane Pastorkovich CONTACT INFORMATION Jeffrey Swoger Antoinette Petrucci Osher Lifelong Learning Institute Randy Weinberg Helen-Faye Rosenblum (SLSG) Richard Wellins Carnegie Mellon University Judy Rubinstein 5000 Forbes Avenue Rochelle Steiner Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3815 Jeffrey Swoger (SLSG) Rebecca Culyba, Randy Weinberg (STSG) Associate Provost During Covid, we prefer to receive an email and University Liaison from you rather than a phone call. Please include your return address on all mail sent to the Osher office. Phone: 412.268.7489 Email: [email protected] Website: cmu.edu/osher ON THE COVER When Andrew Carnegie selected architect Henry Hornbostel to design a technical school in the late 1890s, the plan was for the layout of the buildings to form an “explorer’s ship” in search of knowledge. -

Lesson 1 Introduction to Epidemiology

Lesson 1 Introduction to Epidemiology Epidemiology is considered the basic science of public health, and with good reason. Epidemiology is: a) a quantitative basic science built on a working knowledge of probability, statistics, and sound research methods; b) a method of causal reasoning based on developing and testing hypotheses pertaining to occurrence and prevention of morbidity and mortality; and c) a tool for public health action to promote and protect the public’s health based on science, causal reasoning, and a dose of practical common sense (2). As a public health discipline, epidemiology is instilled with the spirit that epidemiologic information should be used to promote and protect the public’s health. Hence, epidemiology involves both science and public health practice. The term applied epidemiology is sometimes used to describe the application or practice of epidemiology to address public health issues. Examples of applied epidemiology include the following: • the monitoring of reports of communicable diseases in the community • the study of whether a particular dietary component influences your risk of developing cancer • evaluation of the effectiveness and impact of a cholesterol awareness program • analysis of historical trends and current data to project future public health resource needs Objectives After studying this lesson and answering the questions in the exercises, a student will be able to do the following: • Define epidemiology • Summarize the historical evolution of epidemiology • Describe the elements of a case -

Yuri Schwebler the Spiritual Plane

YURI SCHWEBLER THE SPIRITUAL PLANE ALPER INITIATIVE FOR WASHINGTON ART YURI SCHWEBLER THE SPIRITUAL PLANE Curated by John James Anderson American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center Washington, DC ALPER INITIATIVE FOR WASHINGTON ART Untitled (Blue Haystack), c. 1983. Mixed media on paper. Courtesy Enid Sanford. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS During my research on the Jefferson Place Gallery in 2016, I went on a wild lark trying to find an archive for Yuri Schwebler. That resulted in a 3,000 word essay, published on the Inter- national Sculpture Center’s blog, re:sculpt. The article almost didn’t happen, since it was roughly 2,000 words longer than they typi- cally allowed. The web manager, Karin Jevert, fought for the article’s publication. Thanks to her efforts, the article was published, and it generated some renewed interest in Schwe- bler’s work. Throughout the 1990s, Enid Sanford and a Drawing for an Unrealized Sculpture, c. 1979. Mixed media on paper. Courtesy Enid Sanford. group of supporters attempted to organize a memorial exhibition after Yuri’s death. Absent a willing gallery or museum, those efforts didn’t come to fruition. It’s with great gratitude that, 30 years later, Jack Rasmussen gave it the green light: an exhibition between 2 and 3 decades. Despite the cancellation of the exhibition, due Yuri Schwebler, Washington, DC, 1980. Photo by Mary H.D. Swift. to the international pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus, I want to extend my thanks to Jack, Carla Galfano, Sarah Leary, Jessica Pochesci, Kevin Runyon, Kristi-Anne Shaer, and the rest of the staff, assistants, and volunteers who would have helped make this exhibi- tion come together had circumstances remained “normal.” Fortunately, we still have the catalog, and we have Elizabeth Cowgill to thank for that, as well as the generous support of Carolyn Small Alper whose legacy thrives through the exhibitions of Washington art that she championed. -

Michael Clark (A.K.A

ARTIST MICHAEL CLARK: WASHINGTON April 3 – May 27, 2018 American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center Washington, DC ALPER INITIATIVE FOR WASHINGTON ART FOREWORD Michael Clark (a.k.a. Clark Fox) has been an influential figure in the Washington art world for more than 50 years, despite dividing his time equally between the capital and New York City. Clark was not only a fly on the wall of the art world as the last half- century played out—he was in the middle of the action, making innovative works that draw their inspiration from movements as diverse as Pop Art, Op Art, Conceptual Art, Minimalism, and the Washington Color School. The result of this prolific and varied artistic oeuvre is that Clark’s output is too much for one show. After consulting with former Washington Post art critic Paul Richard, I decided Michael Clark: Washington Artist at the American University Museum would concentrate on his significant artistic contributions to the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s in Washington, DC. In line with his amazingly diverse and productive career, a conversation with Michael Clark is similar to drinking from a fire hose. In one sentence, he can jump from painting techniques using masking tape to making cookies for Jackie Onassis. My transcription of our conversation, presented here as a soliloquy, tries its best to maintain some kind of coherence and order, but in reality, I just tried to hold on for the ride. In contrast, the amazing thing about Clark’s art is how still, focused, and composed it is. The leaps and diversions of his lively mind are transmuted into an almost classical art, more Modigliani than Soutine, probably reflecting the time spent in his early years copying masterworks in the National Gallery of Art. -

Life Course Epidemiology D Kuh, Y Ben-Shlomo, J Lynch, J Hallqvist, C Power

778 GLOSSARY Life course epidemiology D Kuh, Y Ben-Shlomo, J Lynch, J Hallqvist, C Power ............................................................................................................................... J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:778–783 The aim of this glossary is to encourage a dialogue that will life course epidemiology has paid particular attention to the long term effects of childhood advance the life course perspective. and adolescent risk factors on later disease. This ........................................................................... is partly a response to the emphasis on adult factors in most post-war aetiological models of life course approach offers an interdisci- chronic disease. This is in contrast with the focus plinary framework for guiding research on of life span developmental psychology on adult health, human development and aging. human development to counter the dominance 1 A 1 23 4 of child centred developmental psychology. Psychologists, sociologists, demographers, anthropologists,5 and biologists6 have actively Life course epidemiology attempts to integrate promoted such an approach for many years. The biological and social risk processes rather than interdisciplinary research area of developmental draw false dichotomies between them. The science,78 also brings together psychological, interests of life course epidemiology overlap with cognitive, and biological research on develop- social epidemiology, that branch of epidemiology mental processes from conception to death. that studies -

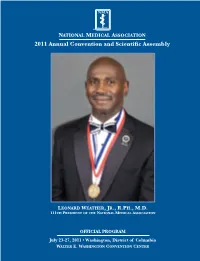

2011 Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly Table of Contents

11-0143 NMA ConvBk_Cvr 6/29/11 2:34 PM Page 1 N ATIONAL M EDICAL NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION 2011 Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly A SSOCIATION 2011 Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly LEONARD WEATHER,JR., R.PH., M.D. 111TH PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION Washington, DC OFFICIAL PROGRAM July 23-27, 2011 • Washington, District of Columbia WALTER E. WASHINGTON CONVENTION CENTER 11-0143 NMA ConvBk_Cvr 6/29/11 2:34 PM Page 2 PLEASE JOIN US NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA July 28 - August 1, 2012 2012ANNUAL CONVENTION AND SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY National Medical Association 8403 Colesville Road, Suite 920 Silver Spring, MD 20910 202-347-1895 www.NMAnet.org July 23-27, 2011 Washington, DC Health Equity: Lead, Reform, Deliver OFFICIAL CONVENTION PROGRAM BOOK* NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION 109TH ANNUAL CONVENTION AND SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY Walter E.Washington Convention Center Related additional information including needs assessment, disclosures, and speaker descriptions will be found in the individual session or section manuals. *This program is subject to change without prior notice. 8403 Colesville Road, Suite 920 Leonard Weather Jr., R.Ph., M.D. Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 President 202.347.1895 Ext. 211 • Fax 202.347.0722 www.NMAnet.org Dear Colleagues and Friends, I am pleased to welcome you to the National Medical Association’s (NMA) 109th Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly. The theme of this year’s meeting – “Health Equity: Lead, Reform, Deliver” references the vital leadership role that the NMA, and its members, must actively play in ensuring that healthcare reform is implemented in all states in a man- ner that results in improved health access, services, and outcomes for all especially our most vulnerable patients. -

Hedda Sterne and Abstract Expressionism

1 Menacing Machines and Sublime Cities: Hedda Sterne and Abstract Expressionism Tasia Kastanek Art History Honors Thesis April 12, 2011 Primary Advisor: Kira van Lil – Art History Committee Members: Robert Nauman – Art History Nancy Hightower – Writing and Rhetoric 2 Abstract: The canon of Abstract Expressionism ignores the achievements of female painters. This study examines one of the neglected artists involved in the movement, Hedda Sterne. Through in-depth analysis of her Machine series and New York, New York series, this study illuminates the differences and similarities of Sterne‟s paintings to the early stages of Abstract Expressionism. Sterne‟s work both engages with and expands the discussions of “primitive” signs, the sublime and urban abstraction. Her early training in Romania and experience of WWII as well as her use of mechanical symbols and spray paint contribute to a similar yet unique voice in Abstract Expressionism. Table of Contents Introduction: An Inner Necessity and Flight from Romania…….…………..……………….3 Machines: Mechanolatry, War Symbolism and an Ode to Tractors……………………......13 New York, New York: Masculine Subjectivity, Urban Abstraction and the Sublime...…...26 Instrument vs. Actor: Sterne’s Artistic Roles………………..………………………….……44 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………49 Images…………………………………………………………………………………………...52 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………..67 3 “Just as each spoken word rouses an internal vibration, so does every object represented. To deprive oneself of this possibility of causing a vibration