Why Europe Abolished Capital Punishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Labour and the Struggle for Socialism

Labour and the Struggle for Socialism An ON THE BRINK Publication WIN Publications Summer 2020 On the Brink Editor: Roger Silverman, [email protected] Published by Workers International Network (WIN), contact: [email protected] Front cover photo: Phil Maxwell Labour and the Struggle for Socialism By Roger Silverman From THE RED FLAG (still the Labour Party’s official anthem) The people’s flag is deepest red, It shrouded oft our martyred dead, And ere their limbs grew stiff and cold, Their hearts’ blood dyed its every fold. CHORUS: Then raise the scarlet standard high. Beneath its shade we’ll live and die, Though cowards flinch and traitors sneer, We’ll keep the red flag flying here. With heads uncovered swear we all To bear it onward till we fall. Come dungeons dark or gallows grim, This song shall be our parting hymn. A Turning Point The recently leaked report of the antics of a clique of unaccountable bureaucrats ensconced in Labour headquarters has sent shock waves throughout the movement. Shock – but little surprise, because these creatures had always been in effect “hiding in plain sight”: ostensibly running the party machine, but actually hardly bothering to conceal their sabotage. All that was new was the revelation of the depths of their venom; their treachery; their racist bigotry; the vulgarity with which they bragged about their disloyalty; their contempt for the aspirations of the hundreds of thousands who had surged into the party behind its most popular leader ever, Jeremy Corbyn. They had betrayed the party that employed them and wilfully sabotaged the election prospects of a Labour government. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Individual Liberty and the Common Good - the Balance: Prayer, Capital Punishment, Abortion

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 20 Number 3 Volume 20, Summer 1974, Number 3 Article 5 Individual Liberty and the Common Good - The Balance: Prayer, Capital Punishment, Abortion Brendan F. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Constitutional Law Commons This Pax Romana Congress Papers is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIVIDUAL LIBERTY AND THE COMMON GOOD-THE BALANCE: PRAYER, CAPITAL PUNISHMENT, ABORTION BRENDAN F. BROWN* In striking the balance between individual freedom and the common good of society, judges are relying "on ideology or policy preference more than on legislative intent."' Professor Jude P. Dougherty, President-elect of the American Catholic Philosophical Association, has declared that "this is particulary apparent in actions of the United States Supreme Court where the envisaged effects of a decision are often given more weight than the intentions of the framers of the Constitution or of the legislators who passed the law under consideration."' The dominant trend of the United States judiciary is to begin its reasoning with "liberty" or "free- dom" as the ultimate moral value in the Franco-American sense of maxi- mum individual self-assertion, and then to maximize it. It will be the purpose of this paper to show that "liberty" or "freedom" is only an instrumental moral value, and that by treating it otherwise, the courts are damaging the common good of society. -

British Responses to the Holocaust

Centre for Holocaust Education British responses to the Insert graphic here use this to Holocaust scale /size your chosen image. Delete after using. Resources RESOURCES 1: A3 COLOUR CARDS, SINGLE-SIDED SOURCE A: March 1939 © The Wiener Library Wiener The © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. Where was the photograph taken? Which country? 2. Who are the people in the photograph? What is their relationship to each other? 3. What is happening in the photograph? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the image. SOURCE B: September 1939 ‘We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack on her people.’ © BBC Archives BBC © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph and the extract from the document. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. The person speaking is British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. What is he saying, and why is he saying it at this time? 2. Does this support the belief that Britain declared war on Germany to save Jews from the Holocaust, or does it suggest other war aims? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the sources. -

British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 William Styles Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge September 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy William Styles British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 This thesis is concerned with an analysis of British governmental attitudes and responses to communism in the United Kingdom during the early years of the Cold War, from the election of the Attlee government in July 1945 up until the election of the Wilson government in October 1964. Until recently the topic has been difficult to assess accurately, due to the scarcity of available original source material. However, as a result of multiple declassifications of both Cabinet Office and Security Service files over the past five years it is now possible to analyse the subject in greater depth and detail than had been previously feasible. The work is predominantly concerned with four key areas: firstly, why domestic communism continued to be viewed as a significant threat by successive governments – even despite both the ideology’s relatively limited popular support amongst the general public and Whitehall’s realisation that the Communist Party of Great Britain presented little by way of a direct challenge to British political stability. Secondly, how Whitehall’s understanding of the nature and severity of the threat posed by British communism developed between the late 1940s and early ‘60s, from a problem considered mainly of importance only to civil service security practices to one which directly impacted upon the conduct of educational policy and labour relations. -

Why Maryland's Capital Punishment Procedure Constitutes Cruel and Unusual Punishment Matthew E

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 37 Article 6 Issue 1 Fall 2007 2007 Comments: The rC ime, the Case, the Killer Cocktail: Why Maryland's Capital Punishment Procedure Constitutes Cruel and Unusual Punishment Matthew E. Feinberg University of Baltimore School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Feinberg, Matthew E. (2007) "Comments: The rC ime, the Case, the Killer Cocktail: Why Maryland's Capital Punishment Procedure Constitutes Cruel and Unusual Punishment," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 37: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol37/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CRIME, THE CASE, THE KILLER COCKTAIL: WHY MARYLAND'S CAPITAL PUNISHMENT PROCEDURE CONSTITUTES CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT I. INTRODUCTION "[D]eath is different ...." I It is this principle that establishes the death penalty as one of the most controversial topics in legal history, even when implemented only for the most heinous criminal acts. 2 In fact, "[n]o aspect of modern penal law is subjected to more efforts to influence public attitudes or to more intense litigation than the death penalty.,,3 Over its long history, capital punishment has changed in many ways as a result of this litigation and continues to spark controversy at the very mention of its existence. -

Journal Officiel Du Lundi 20 Octobre 1980

* Année 1980-1981 . — N° 42 A. N. (O.) Lundi 20 Octobre 1980 * JOURNAL OFFICIEL IDE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE DÉBATS PARLEMENTAIRES ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE CONSTITUTION DU 4 OCTOBRE 1958 6' Législature QUESTIONS ECRITES REMISES A LA PRESIDENCE DE L'ASSEMBLEE NATIONALE ET REPONSES DES MINISTRES 3. Questions écrites pour lesquelles les ministres demandent un SOMMAIRE délai supplémentaire pour rassembler les éléments de leur réponse (p. 4475). 4 . Liste de rappel des questions écrites auxquelles il n 'a pas été 1. Questions écrites (p . 4365). répondu dans les délais réglementaires (p . 475). 2. Réponses des ministres aux questions écrites (p . 4412). Premier ministre (p . 4412). 5. Rectificatifs (p. 4476). Agriculture (p . 4412). Anciens combattants (p . 44181. Budget (p. 44191. Culture et communication (p . 4426). QUESTIONS ECRITES Economie (p . 4426). Education (p . 4428). Environnement et cadre de vie (p. 44341. Transports routiers (politique des transports routiers). Famille et condition féminine (p . 4436). Fonction publique (p . 4437). 36588. — 20 octobre 1980 . — M . Pierre-Bernard Cousté expose à M . le ministre des transports que la profession de transporteur rou- . 4439). Industrie (p tier semble menacée du lait d ' un certain nombre de décisions gou- Industries agricoles et alimentaires (p. 4446). vernementales, qui mettent cette branche d 'activité en difficulté. Intérieur (p . 4446(. Il lui demande, en conséquence, s ' il envisage d 'assouplir l 'usage Jeunesse, sports et loisirs (p . 4452). strict du contrdlographe en laissant aux conducteurs la possibilité de programmer les heures de conduite ; s ' il ne craint pas que les Justice (p . 4452). transports à longue distance, en particulier alimentaires, soient lour- Postes et télécommunications et télédiffusion (p, 4455). -

Arguing for the Death Penalty: Making the Retentionist Case in Britain, 1945-1979

Arguing for the Death Penalty: Making the Retentionist Case in Britain, 1945-1979 Thomas James Wright MA University of York Department of History September 2010 Abstract There is a small body of historiography that analyses the abolition of capital punishment in Britain. There has been no detailed study of those who opposed abolition and no history of the entire post-war abolition process from the Criminal Justice Act 1948 to permanent abolition in 1969. This thesis aims to fill this gap by establishing the role and impact of the retentionists during the abolition process between the years 1945 and 1979. This thesis is structured around the main relevant Acts, Bills, amendments and reports and looks briefly into the retentionist campaign after abolition became permanent in December 1969. The only historians to have written in any detail on abolition are Victor Bailey and Mark Jarvis, who have published on the years 1945 to 1951 and 1957 to 1964 respectively. The subject was discussed in some detail in the early 1960s by the American political scientists James Christoph and Elizabeth Tuttle. Through its discussion of capital punishment this thesis develops the themes of civilisation and the permissive society, which were important to the abolition discourse. Abolition was a process that was controlled by the House of Commons. The general public had a negligible impact on the decisions made by MPs during the debates on the subject. For this reason this thesis priorities Parliamentary politics over popular action. This marks a break from the methodology of the new political histories that study „low‟ and „high‟ politics in the same depth. -

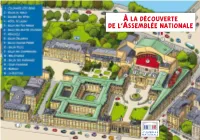

Assemblée Nationale Sommaire

A la découverte de l’Assemblée nationale Sommaire Petite histoire d’une loi (*) ................................... p. 1 à lexique parlementaire ............................................. p. 10 à ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE Secrétariat général de l’Assemblée et de la Présidence Service de la communication et de l’information multimédia www.assemblee-nationale.fr Novembre 2017 ^ Dessins : Grégoire Berquin Meme^ si elle a été proposée par une classe participant au Parlement des enfants en 1999, la loi dont il est question dans cette bande dessinée n’existe pas. Cette histoire est une fiction. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Groupe politique Ordre du Jour lexique Un groupe rassemble des députés C’est le programme des travaux de qui ont des affinités politiques. l’Assemblée en séance publique. parlementaire Les groupes correspondent, Il est établi chaque semaine par en général, aux partis politiques. la Conférence des Présidents, composée des vice-présidents de Guignols l’Assemblée, des présidents de Tribunes situées au-dessus des deux commission et de groupe et d’un Amendement Commission portes d’entrée de la salle des représentant du Gouvernement. Proposition de modification d’un Elle est composée de députés séances. Elle est présidée par le Président projet ou d’une proposition de loi représentant tous les groupes Journal officiel de l’Assemblée. Deux semaines de soumise au vote des parlementaires. politiques. Elle est chargée d’étudier séance sur quatre sont réservées en L’amendement supprime ou modifie et, éventuellement, de modifier les Le Journal Officiel de la République priorité aux textes présentés par le un article du projet ou de la projets et propositions de loi avant française publie toutes les décisions de Gouvernement. -

The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T

MIGRATION,PALGRAVE ADVANCES IN CRIMINOLOGY DIASPORASAND CRIMINAL AND JUSTICE CITIZENSHIP IN ASIA The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y.C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Refecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the feld of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 David T. Johnson The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson University of Hawaii at Mānoa Honolulu, HI, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-030-32085-0 ISBN 978-3-030-32086-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32086-7 This title was frst published in Japanese by Iwanami Shinsho, 2019 as “アメリカ人のみた日本 の死刑”. [Amerikajin no Mita Nihon no Shikei] © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. -

HURST V. FLORIDA

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2015 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus HURST v. FLORIDA CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA No. 14–7505. Argued October 13, 2015—Decided January 12, 2016 Under Florida law, the maximum sentence a capital felon may receive on the basis of a conviction alone is life imprisonment. He may be sentenced to death, but only if an additional sentencing proceeding “results in findings by the court that such person shall be punished by death.” Fla. Stat. §775.082(1). In that proceeding, the sentencing judge first conducts an evidentiary hearing before a jury. §921.141(1). Next, the jury, by majority vote, renders an “advisory sentence.” §921.141(2). Notwithstanding that recommendation, the court must independently find and weigh the aggravating and miti- gating circumstances before entering a sentence of life or death. §921.141(3). A Florida jury convicted petitioner Timothy Hurst of first-degree murder for killing a co-worker and recommended the death penalty. The court sentenced Hurst to death, but he was granted a new sen- tencing hearing on appeal. At resentencing, the jury again recom- mended death, and the judge again found the facts necessary to sen- tence Hurst to death. -

Prison Conditions, Capital Punishment, and Deterrence

Prison Conditions, Capital Punishment, and Deterrence Lawrence Katz, Harvard University and National Bureau of Economic Research, Steven D. Levitt, University of Chicago and American Bar Foundation, and Ellen Shustorovich, City University of New York Previous research has attempted to identify a deterrent effect of capital punishment. We argue that the quality of life in prison is likely to have a greater impact on criminal behavior than the death penalty. Using state-level panel data covering the period 1950±90, we demonstrate that the death rate among prisoners (the best available proxy for prison conditions) is negatively correlated with crime rates, consistent with deterrence. This finding is shown to be quite robust. In contrast, there is little systematic evidence that the execution rate influences crime rates in this time period. 1. Introduction For more than two decades the deterrent effect of capital punishment has been the subject of spirited academic debate. Following Ehrlich (1975), a number of studies have found evidence supporting a deterrent effect of the death penalty (Cloninger, 1977; Deadman and Pyle, 1989; Ehrlich, 1977; Ehrlich and Liu, 1999; Layson, 1985; Mocan and Gittings, 2001). A far larger set of studies have failed to ®nd deterrent effects of capital punishment (e.g., Avio, 1979, 1988; Bailey, 1982; Cheatwood, 1993; Forst, Filatov, and Klein, 1978; Grogger, 1990; Leamer, 1983; Passell and Taylor, 1977).1 Although only one small piece of the broader literature on the issue of We would like to thank Austan Goolsbee for comments and criticisms. The National Science Foundation provided ®nancial support. Send correspondence to: Steven Levitt, Department of Economics, University of Chicago, 1126 E.