Transactional Analysis: a New and Effective Method of Group Therapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Script Symbology Sequence, Duality & Correspondence in Screenplays & Drama

Script Symbology Sequence, Duality & Correspondence in Screenplays & Drama John Fraim John Fraim 189 Keswick Drive New Albany, OH 43054 760-844-2595 [email protected] www.midnightoilstudios.org www.symbolism.org www.desertscreenwritersgroup.com www.greathousestories.com © 2017 – John Fraim FRAIM / SS 1 “Eternal truth needs a human language that varies with the spirit of the times. The primordial images undergo ceaseless transformation and yet remain ever the same, but only in a new form can they be understood anew. Always they require a new interpretation if, as each formulation becomes obsolete, they are not to lose their spellbinding power.” Carl Jung The Psychology of Transference The endless cycle of idea and action, Endless invention, endless experiment, Brings knowledge of motion, but not of stillness; Knowledge of speech, but not of silence; Knowledge of words, and ignorance of the Word. T.S. Eliot The Rock “The essential problem is to know what is revealed to us not by any particular version of a symbol, but by the whole of symbolism.” Mercea Eliade The Rites and Symbols of Initiation “Francis Bacon never tired of contrasting hot and cool prose. Writing in ‘methods’ or complete packages, he contrasted with writing in aphorisms, or single observations such as ‘Revenge is a kind of wild justice. The passive consumer wants packages, but those, he suggested, who are concerned in pursuing knowledge and in seeking causes will resort to aphorisms, just because they are incomplete and require participation in depth.” Marshall McLuhan Understanding Media FRAIM / SS 2 To Eric McLuhan Relentless provocateur over the years FRAIM / SS 3 Contents Preface 8 Introduction 10 I. -

Script Drama Analysis II

10 (1), 21-39 https://doi.org/10.29044/v10i1p21 Script Drama Analysis II © 2019 Stephen B Karpman, MD Abstract In this diagram, the ‘games people play’ of today can be visually linked to the ‘games people played‘ in the This paper completes the original Script Drama childhood family, as illustrated in the four linking Analysis article (Karpman, 1968) that first introduced regression diagrams below, Figures 1, 2, 3, 4. the Drama Triangle, Role Diagram, and Location Diagram into TA script literature. As did the previous By nesting a smaller family drama triangle inside the article, this script theory paper also creates ‘as many larger space of a today's drama triangle, both games new ideas as possible’ to continue Berne's legacy of and script, past and present, are linked visually in a invention by brainstorming as he taught his followers single diagram using connecting arrows, and in his weekly Tuesday night seminars ‘Think Tank’ in confirming the old adage ‘a picture is worth thousand San Francisco in the 1960s. (Karpman, 2014). words’. New game and script theory are woven into novel The first three regression triangles below illustrate the combinations, to open doors and inspire additional script connections that are triggered and baited new script theory. Included are: a) 15 new scripting between the past and the present. The fourth diagram, drama triangles including the Palimpsest, Redecision, the Redecision Triangle, makes that same point but Transference, Freudian, Existential, Miniscript, adding in specific early childhood life decisions into the Biodynamic, and Darwinian Drama Triangles; b) A smaller triangle, to be placed directly along the PRV family games analysis including the child's Redecision positions in the child diagram. -

Life Scripts: Definitions and Points of View

Life Scripts: Definitions and Points of View Richard G. Erskine (Editor), Maria Teresa Tosi, Marye O’Reilly-Knapp, Rosemary Napper, Fanita English, and Jo Stuthridge Abstract The concept of life scripts is but one example The European Association for Transactional of our innovative and evolving theory. The Analysis (EATA) Conference in Prague, the theory of life scripts has fascinated me since I Czech Republic, included a roundtable on first heard about it in 1967 in a training work- “Life Scripts” presented on 9 July 2010. The shop with Fritz Perls. He had borrowed the idea roundtable was preceded by introductory from Eric Berne, but neither Berne nor Perls speeches given by Richard G. Erskine (con- wrote about its psychotherapeutic applications. vener), Maria Teresa (Resi) Tosi, Marye Prior to his untimely death, Berne collected O’Reilly-Knapp, and Jo Stuthridge. The notes and vignettes about various influences in roundtable discussion also included comments the formation of scripts. Those uncorrelated from Rosemary Napper and Fanita English. notes and his ideas about human destiny were This article presents edited excerpts from published as the book What Do You Say After three of the introductory speeches and some You Say Hello? (Berne, 1972). Berne did not of the following discussion. (Jo Stuthridge live long enough to fully develop the concept asked that her speech not be included be- of life scripts; he wrote only an outline of the cause it duplicates material already in print.) theory and did not address how to treat life ______ script issues in psychotherapy. He left it to fu- ture generations, to you, my colleagues here on Richard Erskine, Introduction the roundtable, to me—to all of us—to develop As transactional analysts we have a profound and refine the concepts and methods of work- set of theories that have endured the test of time. -

Life Script Theory: a Critical Review from a Developmental Perspective

This is the Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in the Transactional Analysis Journal, Vol.18, #4, 270-282. 1988, available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/036215378801800402 Life Script Theory: A critical review from a developmental perspective William F. Cornell Great literature has always provided a balance to the lopsided preoccupation of psychological science with pathology . In contrast to the reductionism of science, the model of great literature often enlists an interactionist, longitudinal perspective and seeks to illuminate the myriad forces at work within and without an individual. A novelist would never diminish his protagonist with a finite label. (Felsman & Vaillant, 1987, p. 303) Shortly before his death, Eric Berne (1972), using the analogy of a piano player, wondered if he was actually playing the piano or if he was mostly sitting there while a piano roll determined the tune. As for myself, I know not whether I am still run by a music roll or not. If I am, I wait with interest and anticipation—and without apprehension—for the next notes to unroll their melody, and for the harmony and discord after that. Where will I go next? In this case my life is meaningful because I am following the long and glorious tradition of my ancestors, passed on to me by my parents, music perhaps sweeter than I could compose myself. Certainly I know that there are large areas where I am free to improvise. It may even be that I am one of the few fortunate people on earth who has cast off the shackles entirely and who calls his own tune. -

Arts and Papers ‐ British Institute of Graphologists

ARTS AND PAPERS ‐ BRITISH INSTITUTE OF GRAPHOLOGISTS Author Title a) ANNETTE (Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) The Right Shift Theory of Handwriting and Development Language Problems b) BAKKER (Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) Hemispheric Differences and Reading Strategies: 2 Dyslexia? c) CICCI(Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) Written Language Disorders d) DUANE (Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) A Neurological Overview of Specific Language Disabilities for the Non‐Neurologist e) GESCHWIND (Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) Asymmetries of the Brain: New Developments f) GESCHWIND (Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) Anatomical Evolution and the Human Brain g) GESCHWIND (Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) Why Orton was Right h) MASLAND (Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) Brain Mechanisms Underlying the Language Function i) POLLACK (Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) Neuropsychological Aspects of Reading and Writing j) RAWSON (Orton Dyslexia Society Bulletin) The Structure of English: the Language to be Learned ALSTON & TAYLOR Handwriting Helpline: a guide for parents, teachers, adults and children with handwriting difficulties ASCHAFFENBURG Contribution of Handwriting Analysis to the Examination of Documents BRADLEY Collecting Graphology Books (article in Book and Magazine Collector ‐ Feb 1998) COX & TAPSELL Graphology & its Validity in Personnel Assessment (transcript of paper presented to the British Psychological Society, 1991) FREEDMAN Script Analysis in Transactional Analysis Psychotherapy GRAPHOLOGY SOCIETY Summary of lectures given to the Graphology -

The Redecision Triangle, Makes That Same Point but Adding in Specific Early Childhood

Script Drama Analysis II © 2019 Stephen B. Karpman. This article appeared as Karpman, S (2019) Script Drama Analysis II. International Journal of Transactional Analysis Research & Practice 10: 1 21-39. DOI https://doi.org/10.29044/v10i1p21 When referencing page numbers, the original publication can be accessed free of charge by following the DOI or accessing the journal itself, which is open access, at www.ijtarp.org. Abstract This paper completes the original Script Drama Analysis article (Karpman, 1968) that first introduced the Drama Triangle, Role Diagram, and Location Diagram into TA script literature. As did the previous article, this script theory paper also creates ‘as many new ideas as possible’ to continue Berne's legacy of invention by brainstorming as he taught his followers in his weekly Tuesday night seminars ‘Think Tank’ in San Francisco in the 1960s. (Karpman, 2014). New game and script theory are woven into novel combinations, to open doors and inspire additional new script theory. Included are: a) 15 new scripting drama triangles including the Palimpsest, Redecision, Transference, Freudian, Existential, Miniscript, Biodynamic, and Darwinian Drama Triangles; b) A family games analysis including the child's Redecision Triangle, the Script Game, Script Scene, Script Scene Imago and Dysfunctional Family Analysis; c) Two new script formulae for the Script Game Payoff; d) Three new internal and external Script Energy Drive Systems; e) Three new script reinforcement systems: Script Formula G, Script Formula P3. and a Miniscript Drama Triangle; f) A new three-cornered Darwinian instinct; g) Six new Existential Continuums; and h) Four combination three level script teaching diagrams. -

Script Analysis for Actors, Directors, and Designers, Fourth Edition

Script Analysis for Actors, Directors, and Designers This page intentionally left blank Script Analysis for Actors, Directors, and Designers Fourth Edition James Thomas AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2009, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other- wise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: ( ϩ 44) 1865 843830, fax: ( 44) 1865 853333, E-mail: [email protected] . You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage ( http://elsevier.com ), by selecting “Support& Contact ” then “ Copyright and Permission ” and then“Obtaining Permissions. ” Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Application submitted British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-0-240-81049-2 For information on all Focal Press publications visit our website at www.elsevierdirect.com 09 10 11 12 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America For my respected colleagues at the Moscow Art Theatre School and for the -

1988: Whither Scripts?

Whither Scripts? Fanita English Abstract nell’s statement and his implied criticism of the psychoanalytic emphasis on fixation at child- Script theory, on careful examination, has hood developmental stages, I do not accept a become restrictive, simplistic, and inac- blanket condemnation of psychoanalytic tbink- curate. The author connects Berne’s narrow ing. Clearly the methodology of psychoanalysis deterministic view of scripts to his erroneous is cumbersome and outdated, something Berne view of games. Existential Pattern Therapy recognized even though he continued using (EPT) (English, 1987), the author’s own analysis with some patients almost to the end form of script analysis emphasizing creativi- of his life. Emphasizing linear childhood ty and the balance of unconscious drives, is development without noting interactionist in- described. A case presentation using EPT is fluences, and believing that childhood ex- discussed following which an evaluation of perience is the exclusive cause of later the relationship between unconscious drives behavior, is both limiting and counterproduc- (survival, creative, restful), stroke economy, tive. For example, clinical experience shows and the ego states concludes the analysis. that it is false to assume that a person ‘ ‘fixated’ ’ at one developmental stage cannot progress emotionahy to another until alI issues at the first I applaud Cornell’s (1988) courage in stage are resolved. challenging the constricting tenets on which Even Freud’s (1915/1957) own writings of- current script theory is built. I too, have noted fer openings to the kind of broader views ad- with concern how many TA therapists are vocated by Cornell. However, although I agree shackled to a procrustean bed of unproven that psychological formation can be better beliefs that suggest that injunctions determine understood by considering healthy rather than narrow linear scripts which patients are ex- pathological development, as therapists we also pected to rid themselves of through therapy. -

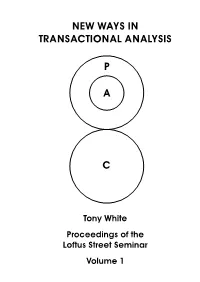

1984. New Ways in Transactional Analysis TA Books

NEW WAYS IN TRANSACTIONAL ANALYSIS P A C Tony White Proceedings of the Loftus Street Seminar Volume 1 NEW WAYS IN TRANSACTIONAL ANALYSIS by TONY WHITE TA BOOKS Distributed by TA Books 136 Loftus Street North Perth WA 6006 Australia +61 (8) 9328 8993 Volume 1. First printing 1984. Second printing 1986. Second edition 2000. Also read: Transference Based Therapy: Theory and practice Proceedings of the Loftus Street Seminar, Volume 2, 1985 How Kids Grow Up and Leave Home: Two years old, four years old, and adolescence Proceedings of the Loftus Street Seminar, Volume 3, 1986 Creative Feeling: How to understand and deal with your child’s feelings! Proceedings of the Loftus Street Seminar, Volume 4, 1986 The Treatment of Character Proceedings of the Loftus Street Seminar, Volume 5, 1987 Adolescence, Anger and What To Do: A happy teenager is not a healthy teenager Proceedings of the Loftus Street Seminar, Volume 6, 1990 all by Tony White. Copyright © 1984 by Anthony Gilbert Browning White. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any process whatsoever without the written permission of the copyright owner, A. G. B. White, 136 Loftus St, North Perth WA 6006, Australia. New Ways in Transactional Analysis Series: Proceedings of the Loftus Street Seminar, Volume 1 by White, Tony (Anthony Gilbert Browning) First published in 1984 by Omega Distributions. This 2nd edition of August 2000 has been OCR scanned from the 1984 edition and reset for publication the Web, and contains minor corrections. See http://www.netword.com/tabooks/ 153 p. : ill. ; 21 cm. -

Transactional Analysis Psychotherapy Three Methods Describing a Transactional Analysis Group Therapy Johnsson, Roland

Transactional Analysis Psychotherapy Three Methods Describing a Transactional Analysis Group Therapy Johnsson, Roland 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Johnsson, R. (2011). Transactional Analysis Psychotherapy: Three Methods Describing a Transactional Analysis Group Therapy. Department of Psychology, Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 TRANSACTIONAL ANALYSIS PSYCHOTHERAPY Three Methods Describing a Transactional Analysis Group Therapy Roland Johnsson LUND UNIVERSITY Department of Psychology 2011 © Roland Johnsson, 2011 Doctoral dissertation Department of Psychology, Lund University Box 213, SE-22100 Lund, Sweden ISBN 978-91-7473-185-9 Cover picture: I am sailing my boat Blue Pram II in the Sound (Öresund). -

Unpacking Elements That Constitute Transgenerational Haunting

Transactional Analysis Journal ISSN: 0362-1537 (Print) 2329-5244 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rtaj20 “Scripting” Inhabitations of Unwelcome Guests, Hosts, and Ghosts: Unpacking Elements That Constitute Transgenerational Haunting Maurice Apprey Interviewed by William F. Cornell To cite this article: Maurice Apprey Interviewed by William F. Cornell (2019): “Scripting” Inhabitations of Unwelcome Guests, Hosts, and Ghosts: Unpacking Elements That Constitute Transgenerational Haunting, Transactional Analysis Journal, DOI: 10.1080/03621537.2019.1650234 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03621537.2019.1650234 Published online: 09 Sep 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 35 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rtaj20 TRANSACTIONAL ANALYSIS JOURNAL https://doi.org/10.1080/03621537.2019.1650234 INTERVIEW “Scripting” Inhabitations of Unwelcome Guests, Hosts, and Ghosts: Unpacking Elements That Constitute Transgenerational Haunting Maurice Apprey Interviewed by William F. Cornell ABSTRACT KEYWORDS A distinction is made between transgenerational transmission and Transgenerational transmis- transgenerational haunting. The former privileges trauma that dis- sion; transgenerational ables the executive functions of the ego, and the latter focuses haunting; sedimentations of on the motivation that underlies the pathway of disturbing ances- history; representational -

Jarosław Jagieła the Family Album and the Script

Jarosław Jagieła The Family Album and the Script Edukacyjna Analiza Transakcyjna 3, 27-44 2014 AKADEMIA IM . JANA DŁUGOSZA W CZĘSTOCHOWIE Edukacyjna Analiza Transakcyjna 2014, nr 3, s. 27–44 http://dx.doi.org/10.16926/eat.2014.03.02 Jarosław JAGIEŁA The Family Album and the Script Keywords: life script, family album, narrative therapy. A picture is worth a thousand words. (a saying) In this article a family album is understood as a carefully catalogued set of photographs or other visual materials illustrating the life of a given family (Photo 1). Photo 1. A family album Source: http://www.google.pl/imgreshl=pl&biw=1280&bih=457&tbm=isch&tbnid=eJYmYfbrw 2NqfM:&imgrefurl=http://www.photoproxima.eu/blog/tag/album-rodzinny&docid=KVtGUVXe 5VQYM&imgurl=http://www.photoproxima.eu/files/blog/b/7_grzeszykowska_album_berlin.jpg& w=676&h=428&ei=3BqbUsvkLYiDhQedj4CgBw&zoom=1&iact=hc&vpx=220&vpy=7&dur=62 5&hovh=179&hovw=282&tx=191&ty=124&page=3&tbnh=122&tbnw=195&start=32&ndsp=19 &ved=1t:429,r:33,s:0,i:193, [accessed on 13.12.2013]. 28 Jarosław JAGIEŁA One of the authors specializing with family photography wrote: When most people reach for their family albums filled with the pictures of the people they love, they experience a special kind of sentiment: while watching the photographs we are looking at people who are important to us and still alive, those who are dead (or maybe it should be said that it is they who are looking at us), and at ourselves when we were young and so different (Musello, 1979, as cited in: Olechnicki, 2009, p.