Israel: a Social Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mediterranean Coast of Israel Is a New City,Now Under

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Theses and Major Papers Marine Affairs 12-1973 The editM erranean Coast of Israel: A Planner's Approach Sophia Professorsky University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/ma_etds Part of the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Professorsky, Sophia, "The eM diterranean Coast of Israel: A Planner's Approach" (1973). Theses and Major Papers. Paper 146. This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Marine Affairs at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Major Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. l~ .' t. ,." ,: .. , ~'!lB~'MEDI'1'ERRANEAN-GQAsT ~F.~"IsMt~·;.·(Al!~.oS:-A~PROACH ::".~~========= =~.~~=~~~==b======~~==~====~==.=~=====~ " ,. ••'. '. ,_ . .. ... ..p.... "".. ,j,] , . .;~ ; , ....: ./ :' ",., , " ",' '. 'a ". .... " ' ....:. ' ' .."~".,. :.' , v : ".'. , ~ . :)(A;R:t.::·AF'~~RS'· B~NMi'»APER. '..":. " i . .: '.'-. .: " ~ . : '. ". ..." '-" .~" ~-,.,. .... .., ''-~' ' -.... , . ", ~,~~~~"ed .' bYr. SOph1a,Ji~ofes.orsJcy .. " • "..' - 01 .,.-~ ~ ".··,::.,,;$~ld~~:' ·to,,:" f;~f.... ;)J~:Uexa~d.r . -". , , . ., .."• '! , :.. '> ...; • I ~:'::':":" '. ~ ... : .....1. ' ..~fn··tr8Jti~:·'btt·,~e~Mar1ne.~a1~S·~r~~. ", .:' ~ ~ ": ",~', "-". ~_"." ,' ~~. ;.,·;·X;'::/: u-=" .. _ " -. • ',. ,~,At:·;t.he ,un:lvers:U:~; tif Rh~:<:rs1..J\d. ~ "~.; ~' ~.. ~,- -~ !:).~ ~~~ ~,: ~:, .~ ~ ~< .~ . " . -, -. ... ... ... ... , •• : ·~·J;t.1l9ston.l~~;&:I( .. t)eceiDber; 1~73.• ". .:. ' -.. /~ NOTES, ===== 1. Prior to readinq this paper, please study the map of the country (located in the back-eover pocket), in order to get acquain:t.ed with names and locations of sites mentioned here thereafter. 2.- No ~eqaJ. aspects were introduced in this essay since r - _.-~ 1 lack the professional background for feedinq in tbe information. -

Emergency in Israel

Emergency in Israel Emergency Update on Jewish Agency Programming May 16, 2021 The recent violent events that have erupted across the country have left us all surprised and stunned: clashes with Palestinians in Jerusalem and on the Temple Mount; the deteriorating security tensions and the massive barrage of missiles from Gaza on southern and central Israel; and the outbreak of unprecedented violence, destruction, and lynching in mixed cities and Arab communities. To say that the situation is particularly challenging is an understatement. We must all deal with the consequences of the current tensions. Many of us are protecting family, coworkers, or people under our charge while missiles fall on our heads night and day, forcing us to seek shelter. We have all witnessed the unbearable sights of rioting, beating, and arson by Arab and Jewish extremists in Lod, Ramla, Acre, Kfar Qassem, Bat Yam, Holon, and other places. As an organization that has experienced hard times of war and destruction, as well as periods of prosperity and peace, it is our duty to rise up and make a clear statement: we will support and assist populations hit by missile fire as we did in the past, after the Second Lebanon War and after Operations Cast Lead and Protective Edge. Together with our partners, we will mobilize to heal and support the communities and populations affected by the fighting. Our Fund for Victims of Terror is already providing assistance to bereaved families. When the situation allows it, we will provide more extensive assistance to localities and communities that have suffered damage and casualties. -

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

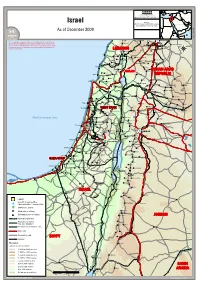

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

Focuspoint International 866-340-8569 861 SW 78Th Avenue, Suite B200 [email protected] Plantation, FL 33324 SUMMARY NN02

INFOCUS QUARTERLY SUMMARY TERRORISM & CONFLICT, NATURAL DISASTERS AND CIVIL UNREST Q2 2021 FocusPoint International 866-340-8569 861 SW 78th Avenue, Suite B200 [email protected] Plantation, FL 33324 www.focuspointintl.com SUMMARY NN02 NATURAL DISASTERS Any event or force of nature that has cyclone, hurricane, tornado, tsunami, volcanic catastrophic consequences and causes eruption, or other similar natural events that give damage or the potential to cause a crisis to a rise to a crisis if noted and agreed by CAP customer. This includes an avalanche, FocusPoint. landslide, earth quake, flood, forest or bush fire, NUMBER OF INCIDENTS 32 3 3 118 20 9 Asia Pacific 118 Sub-Saharan Africa 20 Middle East and North Africa 3 Europe 32 Domestic United States and Canada 3 Latin America 9 MOST "SIGNIFICANT" EVENTS • Indonesia: Tropical Cyclone Seroja • Canada: Deaths in connection with • DRC: Mt. Nyiragongo eruption an ongoing heatwave • Algeria: Flash Floods • Panama: Floods/Landslides • Russia: Crimea and Krasnodar Krai flooding 03 TERRORISM / CONFLICT Terrorism means an act, including but not government(s), committed for political, limited to the use of force or violence and/or the religious, ideological or similar purposes threat thereof, of any person or group(s) of including the intention to influence any persons, whether acting alone or on behalf of or government and/or to put the public, or any in connection with any organization(s) or section of the public, in fear. NUMBER OF INCIDENTS 20 1 270 209 144 15 Asia Pacific 209 Sub-Saharan Africa 144 Middle East and North Africa 270 Europe 20 Domestic United States and Canada 1 Latin America 15 MOST "SIGNIFICANT" EVENTS • Taliban Attack on Ghazni • Tigray Market Airstrike • Solhan Massacre • Landmine Explosion 04 POLITICAL THREAT / CIVIL UNREST The threat of action designed to influence the purposes of this travel assistance plan, a government or an international governmental political threat is extended to mean civil threats organization or to intimidate the public, or a caused by riots, strikes, or civil commotion. -

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

Timeline of Shīʿī History in Palestine

Timeline of Shīʿī History in Palestine Umayyads – Early second/eighth century: People from Palestine send a convoy to the Imām Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq. ʿAbbāsids – Second half of the third/ninth century: The geographer al-Yaʿqūbī mentions the settlement of the Shīʿī ʿĀmila tribe in the Jund Filasṭīn. – 271/884: Muḥammad b. Ḥamza, a descendant of al-ʿAbbās b. ʿAlī, is murdered in Tiberias by Ṭughj b. Juff the Ikhshīdid. – 289–90/902–03: The Ismāʿīlī mahdī of Salamiyya, ʿAbdallāh al-Mahdī, hides in Ramla. – First half of the fourth/tenth century: The Persian Shīʿī poet Kushājim sojourns in Ramla. Fāṭimids – Second half of the fourth/tenth century: The geographer Muḥammad al-Maqdisī complains that all Tiberias, half of Nablus, and Qadas are Shīʿīs. – 360–67/970–77: The Qarmaṭī invasion of Palestine is centered in Ramla. – 363–64/973–74: Authorities imposed Shīʿī customs in Palestine, two Sunnīs from Ramla and Jerusalem who opposed it were detained and tortured. – 386/996: Shīʿī messianic rebellion of Abū l-Futūḥ Ḥasan b. Jaʿfar, the amīr of Mecca in Ramla. – First half of the fifth/eleventh century: – Shīʿī genealogist Najm al-Dīn al-ʿUmarī travels through Ramla, and mentions several Ṭālibiyyūn (descendants of the Imāms) in Jerusalem, Tiberias, and Ramla. – The Sunnī Ibn Ḥazm al-Andalusī complains that all of Urdunn (that is, Galilee), mainly Tiberias, is controlled by the Nuṣayrīs (now ʿAlawīs). – Druzes/Ḥākimī spread propaganda in Galilee (al-Buqayʿa) and Ḥamza’s oppo- nents are mentioned in Acre. © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004421028_015 Yaron Friedman - 9789004421028 Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 04:13:15AM via free access Timeline 203 – Mid-fifth/eleventh century: The traveler Nāṣir Khusraw mentions Shīʿīs in Tiberias and Fāṭimid investment and construction projects in Palestine. -

The Beit Shemesh Running Club

The Beit Shemesh Running Club Marathoners Unite Religiously Diverse Israeli City By Hillel Kuttler pon completing each Monday’s 90-min- Strous could also have been referring to the ath- ute group run at 10:30 p.m., Rael Strous letic group to which he belongs, the Beit Shemesh Utakes leave of his mates and drives to a Running Club. The club unites disparate Jewish nearby bakery whose fresh-from-the-oven whole segments of society around a common appetite wheat rolls he craves. for pavement and trails, then sends them and Dripping 10 miles’ worth of street-pounding their differences home until the next workout. sweat and still clad in running shorts, Strous tends Its members and town officials view the run- to draw gazes and conversational interest from the ning club as a stark example of sports’ power to black-hatted, black-coated ultra-Orthodox men foster tolerance and inclusion. That is no small Members of the Beit who likewise visit the bakery for a late nibble here feat, especially following a series of ugly incidents Shemesh Running Club, in Beit Shemesh, an unassuming city of 85,000, in late 2011 near a Beit Shemesh elementary Shlomo Hammer and his 20 miles west of Jerusalem. The curiosity seekers school that had just opened on property that father Naftali Hammer inquire about Strous’ workout; he asks what Jewish adjoins—but also divides—the separate neigh- (front right and front scholarly texts they’ve been studying. borhoods where Modern Orthodox and ultra- left), stretching before “It’s just a bunch of guys getting together, Orthodox Jews live. -

Israel and the Occupied Territories 2015 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, the parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve the government and mandate elections. The nationwide Knesset elections in March, considered free and fair, resulted in a coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. (An annex to this report covers human rights in the occupied territories. This report deals with human rights in Israel and the Israeli- occupied Golan Heights.) During the year according to Israeli Security Agency (ISA, also known as Shabak) statistics, Palestinians committed 47 terror attacks (including stabbings, assaults, shootings, projectile and rocket attacks, and attacks by improvised explosive devices (IED) within the Green Line that led to the deaths of five Israelis and one Eritrean, and two stabbing terror attacks committed by Jewish Israelis within the Green Line and not including Jerusalem. According to the ISA, Hamas, Hezbollah, and other militant groups fired 22 rockets into Israel and in 11 other incidents either planted IEDs or carried out shooting or projectile attacks into Israel and the Golan Heights. Further -

SCHOLARSHIP OPPORTUNITIES at TAU the International MA

SCHOLARSHIP OPPORTUNITIES AT TAU The International MA Program in Ancient Israel Studies: Archaeology and History of the Land of the Bible at Tel Aviv University is pleased to announce three scholarship opportunities for the academic year 2015-2016. 1. $13,000 US AYALIM TUITION ASSISTANCE SCHOLARSHIP A number of $13,000 US tuition assistance scholarships are offered to students who meet the following requirements: * Applicant's age must range from 21 to 30. * Applicant must be recognized by Masa Israel Journey (according to Masa's criteria for scholarships). 2. $2,500/ 5,000 US TUITION ASSISTANCE SCHOLARSHIPS $2,500/ 5,000 USD tuition assistance scholarships will be granted to a number of students with proven records of academic excellence who wish to broaden their knowledge and understanding of Ancient Israel. Scholarships for the academic year of 2015-2016 will be granted by the academic committee of the Department of Archaeology and Near Eastern Cultures based on the following: * Academic CV * Final transcript from last academic establishment * Abstract of the final paper submitted to the last academic establishment 3. FULL TUITION SCHOLARSHIPS FOR STUDENTS FROM CHINA Full tuition scholarships will be awarded based on academic excellence, and will allow students from China to study the archaeology and history of the Land of the Bible - IN the land of the Bible, at one of the most prestigious programs currently available in the field of Ancient Israel Studies. A number of accepted students will also be awarded free dormitories and living expense grants, in addition to full tuition scholarships. Admission requirements for students from China: * Academic achievements: Students must have a GPA of 3 or above, or an average score of 80% from their BA degree. -

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES MOTHER's SCHOOLING, FERTILITY, and CHILDREN's EDUCATION: EVIDENCE from a NATURAL EXPERIMENT Victor

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES MOTHER'S SCHOOLING, FERTILITY, AND CHILDREN'S EDUCATION: EVIDENCE FROM A NATURAL EXPERIMENT Victor Lavy Alexander Zablotsky Working Paper 16856 http://www.nber.org/papers/w16856 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2011 We benefited from comments by Josh Angrist, Esther Duflo, Ephraim Kleinman, Melanie Luhrmann, Daniele Paserman, Steve Pischke, Yona Rubinstein, Natalia Weisshaar, Asaf Zussman and seminar participants at the Bocconi University, Hebrew University, LSE, NBER Labor Studies conference in Autumn 2010, Oxford University, RH University of London, Tel Aviv University, and University of Zurich. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2011 by Victor Lavy and Alexander Zablotsky. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Mother's Schooling, Fertility, and Children's Education: Evidence from a Natural Experiment Victor Lavy and Alexander Zablotsky NBER Working Paper No. 16856 March 2011 JEL No. I1,J2 ABSTRACT This paper studies the effect of mothers‘ education on their fertility and their children‘s schooling. We base our evidence on a natural experiment that sharply reduced the cost of attending school and, as a consequence, significantly increased the education of affected cohorts. This natural experiment was the result of the de facto revocation in October 1963 of the military rule that had been imposed on Arabs in Israel, immediately creating free access to institutions of schooling. -

Sukkot Real Estate Magazine

SUKKOT 2020 REAL ESTATE Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Living the high Life LETTER FROM THE EDITOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Dear Readers, With toWers Welcome to the Sukkot edition of The Jerusalem THE ECONOMY: A CHALLENGING CONUNDRUM ....................08 Post’s Real Estate/Economic Post magazine. Juan de la Roca This edition is being published under the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic. Although not all the articles herein are related to the virus, it is a reality BUILDING A STRONGER FUTURE ............................................... 12 that cannot be ignored. -

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Research and writing: Michal Belikoff and Safa Ali Agbaria Editing: Shirley Racah Steering committee: Samah Elkhatib-Ayoub, Ron Gerlitz, Azar Dakwar, Mohammed Khaliliye, Abed Kanaaneh, Jabir Asaqla, Ghaida Rinawie Zoabi, and Shirley Racah Critical review and assistance with research and writing: Ron Gerlitz and Shirley Racah Academic advisor: Dr. Nahum Ben-Elia Co-directors of Sikkuy’s Equality Policy Department: Abed Kanaaneh and Shirley Racah Project director for Injaz: Mohammed Khaliliye Hebrew language editing: Naomi Glick-Ozrad Production: Michal Belikoff English: IBRT Jerusalem Graphic design: Michal Schreiber Printed by: Defus Tira This pamphlet has also been published in Arabic and Hebrew and is available online at www.sikkuy.org.il and http://injaz.org.il Published with the generous assistance of: The European Union This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Sikkuy and Injaz and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The Moriah Fund UJA-Federation of New York The Jewish Federations of North America Social Venture Fund for Jewish-Arab Equality and Shared Society The Alan B.