Final Testament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pessi and Dovie Levy ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א the 17Th of August, 2021 © 2021

לזכות החתן הרה"ת שלום דובער Memento from the Wedding of והכלה מרת פעסיל ליווי Pessi and Dovie ולזכות הוריהם Levy מנחם מענדל וחנה ליווי ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א הרב שלמה זלמן הלוי וחנה זיסלא The 17th of August, 2021 פישער שיחיו לאורך ימים ושנים טובות Bronstein cover 02.indd 1 8/3/2021 11:27:29 AM בס”ד Memento from the Wedding of שלום דובער ופעסיל שיחיו ליווי Pessi and Dovie Levy ט‘ אלול ה‘תשפ“א The 17th of August, 2021 © 2021 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, in any form, without prior permission, in writing. Many of the photos in this book are courtesy and the copyright of Lubavitch Archives. www.LubavitchArchives.com [email protected] Design by Hasidic Archives Studios www.HasidicArchives.com [email protected] Printed in the United States Contents Greetings 4 Soldiering On 8 Clever Kindness 70 From Paris to New York 82 Global Guidance 88 Family Answers 101 Greetings ,שיחיו Dear Family and Friends As per tradition at all momentous events, we begin by thanking G-d for granting us life, sustain- ing us, and enabling us to be here together. We are thrilled that you are able to share in our simcha, the marriage of Dovie and Pessi. Indeed, Jewish law high- lights the role of the community in bringing joy to the chosson and kallah. In honor of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin’s wedding in 1928, the Frierdiker Rebbe distributed a special teshurah, a memento, to all the celebrants: a facsimile of a letter written by the Alter Rebbe. -

T S Form, 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

t s Form, 990-PF Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state report! 2006 For calendar year 2006, or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that a Initial return 0 Final return Amended return Name of identification Use the IRS foundation Employer number label. Otherwise , HE DENNIS BERMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 31-1684732 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite Telephone number or type . 5410 EDSON LANE 220 301-816-1555 See Specific City or town, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here l_l Instructions . state, ► OCKVILLE , MD 20852-3195 D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Foreign organizations meeting 2. the 85% test, ► H Check type of organization MX Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation = Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt chartable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method 0 Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, col (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 5 010 7 3 9 . (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) under section 507 (b)( 1 ► )( B ) , check here ► ad 1 Analysis of Revenue and Expenses ( a) Revenue and ( b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) may not for chartable purposes necessary equal the amounts in column (a)) expenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions , gifts, grants , etc , received 850,000 . -

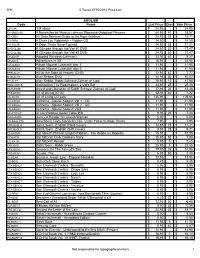

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price Disc Sale Price EO-334I 334 Ideas $ 24.95 $ 24.95 EY-5NOV.SB 5 Novelettes by Marcus Lehman Slipcased (Adopted Princess, $ 64.95 40 $ 38.97 EF-60DA 60 Days Spiritual Guide to the High Holidays $ 24.95 25 $ 18.71 CD-DIRA A Dirah Loy Yisboraich - Yiddish CD $ 14.50 $ 14.50 EO-DOOR A Door That's Never Locked $ 14.95 25 $ 11.21 DVD-GLIM1 A Glimpse through the Veil #1 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 DVD-GLIM2 A Glimpse through the Veil #2 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 EY-ADOP Adopted Princess (Lehman) $ 13.95 40 $ 8.37 EY-ADVE Adventures in 3D $ 16.95 $ 16.95 CD-ALBU1 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 1 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ALBU2 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 2 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 ERR-ALLF All for the Sake of Heaven (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 DVD-ALTE Alter Rebbe, DVD $ 14.95 30 $ 10.47 EY-ALTE Alter Rebbe: Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 19.95 10 $ 17.96 EMO-ANTI.S Anticipating The Redemption, 2 Vol's Set $ 33.95 25 $ 25.46 EAR-ARRE Arrest and Liberation of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 17.95 25 $ 13.46 ETZ-ARTO Art of Giving (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 CD-ARTO Art of Living CD sets $ 125.95 $ 125.95 CD-ASHR1 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 1 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR2 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 2 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR3 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol3 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 EP-ATOU.P At Our Rebbes' Seder Table P/B $ 9.95 25 $ 7.46 EWO-AURA Aura - A Reader On Jewish Woman $ 5.00 $ 5.00 CD-BAALSTS Baal Shem Tov's Storyteller CD - Uncle Yossi Heritage Series $ 7.95 $ 7.95 EFR-BASI.H Basi L'Gani - English (Hard Cover) -

NISSAN Rosh Chodesh Is on Sunday

84 NISSAN The Molad: Friday afternoon, 4:36. The moon may be sanctified until Shabbos, the 15th, 10:58 a.m.1 The spring equinox: Friday, the 7th, 12:00 a.m. Rosh Chodesh is on Shabbos Parshas Tazria, Parshas HaChodesh. The laws regarding Shabbos Rosh Chodesh are explained in the section on Shabbos Parshas Mikeitz. In the Morning Service, we recite half-Hallel, then a full Kaddish, the Song of the Day, Barchi nafshi, and then the Mourner’s Kaddish. Three Torah scrolls are taken out. Six men are given aliyos for the weekly reading from the first scroll. A seventh aliyah is read from the second scroll, from which we read the passages describing the Shabbos and Rosh Chodesh Mussaf offerings (Bamidbar 28:9-15), and a half-Kaddish is recited. The Maftir, a passage from Parshas Bo (Sh’mos 12:1-20) which describes the command to bring the Paschal sacrifice, is read from the third scroll. The Haftorah is Koh amar... olas tamid (Y’chezkel 45:18-46:15), and we then add the first and last verses of the Haftorah Koh amar Hashem hashomayim kis’ee (Y’shayahu 66:1, 23- 24, and 23 again). Throughout the entire month of Nissan, we do not recite Tachanun, Av harachamim, or Tzidkas’cha. The only persons who may fast during this month are ones who had a disturbing dream, a groom and bride on the day of their wedding, and the firstborn on the day preceding Pesach. For the first twelve days of the month, we follow the custom of reciting the Torah passages describing the sacrifices which the Nesi’im (tribal leaders) offered on these dates at the time the Sanctuary was dedicated in the desert. -

Colel Chabad

Pioneer on Campus INTERVIEW WITH RABBI NOSSON GURARY A Memorable Farewell "חדש THE REBBE’S PARTING OF השביעי THE GUESTS AFTER TISHREI שהוא המושבע והמשביע ברוב טוב לכל ישראל על כל Colel השנה” Chabad THE REBBEIM’S TZEDAKA $5.95 CHESHVAN 5778 ISSUE 62 (139) CHESHVAN 5778 DerherContents ISSUE 62 (139) JEM 194244 JEM 271474 A Chassidisher Derher Magazine is a publication geared toward bochurim, published and copyrighted by Vaad Talmidei Hatmimim Haolomi. All articles in this publication are original content by the staff of A Chassidisher Derher. Vaad Talmidei Hatmimim Rabbi Tzvi Altein Director Rabbi Yossi Kamman Rain of Blessings Is Hafatzas Editor in Chief Rabbi Mendel Jacobs 4 DVAR MALCHUS 32 Hamaayanos Only Editors The way to Celebrate for Chabad? Rabbi Sholom Laine YECHIDUS 5 KSAV YAD KODESH Rabbi Eliezer Zalmanov Rabbi Moshe Zaklikovsky Chassidus for All Pioneer on Campus INTERVIEW WITH RABBI Advisory Committee LEBEN MITTEN REBBEN - 6 34 NOSSON GURARY Rabbi Mendel Alperowitz MAR-CHESHVAN 5751 Rabbi Dovid Olidort Yidden or Beis Maggid of Mezritch Design TIMELINE 46 Hamikdash? Rabbi Mendy Weg 12 MOSHIACH Colel Chabad Printed by The Print House THE REBBEIM’S TZEDAKA Yechidus 14 Photo Credits 48 8 FACTS Colel Chabad Archives בכל דרכיך דעהו DARKEI HACHASSIDUS You Won! Jewish Educational Media 27 DER REBBE VET GEFINEN A VEG The Shepherd 50 Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad Rabbi Pinny Lew in the Pit A Memorable 30 Dubov Family A CHASSIDISHE MAISE 52 Farewell MOMENTS Gurary Family Raskin Family Archives Special Thanks to Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook Rabbi Avraham Gurary About the Cover: Rabbi Zalman Duchman The Colel Chabad Pushka has been a staple of Rabbi Nissan Dovid Dubov every Lubavitch home for generations. -

Day-By-Day Halachic Guide

Day-by-Day Halachic Guide Detailed instructions on the laws and customs for the month of Tishrei 5776 Year of Hakhel Part Two: Erev Sukkos–Hoshana Rabba [Part three will include Hoshana Rabba–Shabbos Bereishis and will be published separately.] From the Badatz of Crown Heights לעילוי נשמת הרה״ח הרה״ת אליהו ציון בן הרה״ח הרה״ת חנני׳ ז״ל נפטר ז״ך ניסן תשע״ג ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. ע״י משפחתו שיחיו h g לעילוי נשמת הרהח הרה״ת ר׳ צבי הירש בהרה״ח ר׳ בן ציון ז״ל שפריצער נלב״ע ז״ך אלול ה׳תש״מ ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. h g לזכות לוי יצחק בן רייזל לרפואה שלימה h g לזכות הרה״ת שניאור זלמן וזוגתו מרת שמחה רבקה שיחיו וילדיהם: אסתר ברכה, איטא העניא, אברהם משה, חי׳ בתי׳ וחנה שיחיו Section III will be available b’ezras Hashem on Erev Shabbos and Erev Yom Tov outside "770" and outside Mikvah Meir. If you would like sponsor this or future publications, d f youor supportcan do so our by Rabbonimcalling: (347) financially, 465-7703 or at www.crownheightsconnect.com (This website has been created by friends of the Badatz) By the Badatz of Crown Heights 3 B”H Day-by-Day Halachic Guide Detailed instructions on the laws and customs for the month of Tishrei 5776 Year of Hakhel Part Two: Erev Sukkos–Hoshana Rabba [Part three will include Hoshana Rabba–Shabbos Bereishis and will be published separately.] The following points were distilled from a series of public shiurim that were delivered by Horav Yosef Yeshaya Braun, member of the Badatz of Crown Heights The basic laws and customs presented below are derived from multiple sources. -

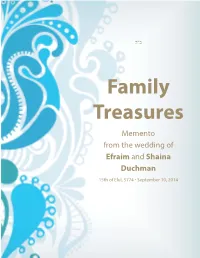

R Zalman Duchman.Indd

ב"ה Family Treasures Memento from the wedding of Efraim and Shaina Duchman 15th of Elul, 5774 • September 10, 2014 Prepared by Dovid Zaklikowski ([email protected]). The Rebbe at the wedding of chosson's grandparents, Mendel and Sara Shemtov, 10 Tamuz, 5716 (June 19th, 1956). In the center (wearing glasses), is his great-grandfather, Reb Zalman Duchman. WELCOME To our dear family and friends, At all joyous events we begin by thanking G-d for granting us life, sustaining us and enabling us to be here together. We are thrilled that you are here to share in our simcha - joyous occasion. Indeed, Jewish law enjoins the entire community to bring joy and elation to the chosson and kallah - the bride and groom. The wedding of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory, took place in Warsaw in 1928. In honor of the occasion, the bride’s father, the sixth Chabad Rebbe, distributed a special teshurah, memento, to all the celebrants: a facsimile of a manuscript letter written by the first Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi. Following this tradition, we are honored to present our memento: a compilation of letters Rabbi Schneur Zalman Duchman, Efraim’s paternal great-grandfather, received from the Rebbe. This is an excerpt from the forthcoming book of stories, translated into English for the first time. This memento is crowned with Mazel Tov wishes from the Rebbe to Shaina's parents and from Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka and Rebbetzin Chana, the Rebbe's mother, to her grandparents, Rabbi Asher and Nechama Heber, may they be blessed with many more happy and healthy years. -

TISHREI Rosh Hashanah Begins on Friday Night. When

9 TISHREI The Molad: Monday night, 11:27 and 11 portions.1 The moon may be sanctified until Tuesday, the 15th, 5:49 p.m.2 The fall equinox: Thursday, Cheshvan 1, 9:00 a.m. Rosh HaShanah begins on Monday night. When lighting candles, we recite two blessings: L’hadlik ner shel Yom HaZikaron (“...to kindle the light of the Day of Remembrance”) and Shehecheyanu (“...who has granted us life...”). (In the blessing should be vocalized לזמן Shehecheyanu, the word lizman, with a chirik.) Tzedakah should be given before lighting the candles. Girls should begin lighting candles from the age when they can be trained in the observance of the mitzvah.3 Until marriage, girls should light only one candle. The Rebbe urged that all Jewish girls should light candles before Shabbos and festivals. Through the campaign mounted at his urging, Mivtza Neshek, the light of the Shabbos and the festivals has been brought to tens of thousands of Jewish homes. A man who lights candles should do so with a blessing, but should not recite the blessing Shehecheyanu.4 The Afternoon Service before Rosh HaShanah. “Regarding the issue of kavanah (intent) in prayer, for those who do not have the ability to focus their kavanah because of a lack of knowledge or due to other factors... it is sufficient that they have in mind a general intent: that their prayers be accepted before Him as if they were recited with all the intents 1. One portion equals 1/18 of a minute. 2. The times for sanctifying the moon are based on Jerusalem Standard Time. -

מחירון תשפ״א 5781 Price List Hei Teves Sale List

m e r k o s k e h o t a n n u a l UP TO week-long sales event BUY IN STORE AND GET A STORE HOURS THU 10AM-7PM FRI 10AM-1PM SAT NIGHT 7:30PM-12AM $ COUPON SUN 10AM-11PM MON-WED 10AM-7PM 5 PER $100 SPENT .Valid for 6 months for in-store purchases made after Hei Teves Sale* מחירון תשפ״א 5781 PRICE LIST HEI TEVES SALE LIST New Since Hei Teves 5780 4 Popular Sets Collection 7 $ Select Sets for 35 or Less 6 HEBREW SEFORIM 17 כ"ק הרב לוי יצחק 9 כ"ק הבעל שם טוב 17 ביוגרפיה וסיפורים 9 כ"ק הרב המגיד ממעזריטש 9 כ"ק אדמו"ר הזקן 18 קובצים קונטרסים 11 כ"ק אדמו''ר האמצעי 19 הלכה ומנהג 11 כ"ק אדמו"ר הצמח צדק 20 שונות 12 כ"ק אדמו"ר מהר"ש 24 עניני תפלה 13 כ"ק אדמו"ר מוהרש"ב 25 לילדים ונוער 13 כ"ק אדמו"ר מוהריי''צ 27 אידיש 14 כ"ק אדמו"ר זי"ע ENGLISH The Baal Shem Tov 28 Torah & Holidays 30 R Schneur Zalman of Liadi 28 Laws & Customs 31 R DovBer of Lubavitch 29 R Menachem Mendel, Prayer 31 the "Tzemach Tzedek" 29 Mysticism 32 R Shmuel, fourth Lubavitcher Rebbe 29 Miscellaneous 33 R Shalom DovBer, History & Biography 35 fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe 29 R Yosef Yitzchak, Toddlers & Preschool 35 sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe 29 Kids & Teens 36 The Lubavitcher Rebbe, R Menachem M Schneerson 29 Multimedia 38 FOREIGN LANGUAGES French 38 Russian 40 German 39 Spanish 41 Italian 39 Swedish 42 Portuguese 39 FIRST COME FIRST SERVE, NO LAYAWAY, NO RAINCHECK. -

Fine Judaica: Printed Books, Manuscripts, Holy Land Maps & Ceremonial Objects, to Be Held June 23Rd, 2016

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, holy land maps & Ceremonial obJeCts K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, Ju ne 23r d, 2016 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 147 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, HOLY LAND MAPS & CEREMONIAL OBJECTS INCLUDING: Important Manuscripts by The Sinzheim-Auerbach Rabbinic Dynasty Deaccessions from the Rare Book Room of The Hebrew Theological College, Skokie, Ill. Historic Chabad-related Documents Formerly the Property of the late Sam Kramer, Esq. Autograph Letters from the Collection of the late Stuart S. Elenko Holy Land Maps & Travel Books Twentieth-Century Ceremonial Objects The Collection of the late Stanley S. Batkin, Scarsdale, NY ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 23rd June, 2016 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 19th June - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 20th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 21st June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 22nd June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Consistoire” Sale Number Sixty Nine Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th Street, 12th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . -

International Conference of Shluchim

International Conference of Shluchim כ״ב - כ״ז חשון, ה״תשע״ג November 7 - 12, 2012 Lubavitch World Headquaters 770 Eastern Parkway Crown Heights, NY toWelcome the International Conference of Shluchim 5773/2012 The presence of thousands of shluchim from around the world has become an annual testament to the scope of the Rebbe’s enduring vision. The sheer greatness and power of this event is unmistakable but this is only because of your participation. As the Rebbe often stressed, every single Shliach’s involvement and contribution to the kinus is essential to its function as a whole. Just as every limb is integral to the health of the human body, every shliach is vital to the success of our mission: .להכין עצמו והעולם כולו לקבלת פני משיח צדקנו and לתקן עולם במלכות ש-ד-י During our brief time together, the Kinus serves as a spiritual oasis. Here we can benefit from the wealth of resources presented and the supercharged atmosphere of so many talented individuals gathered in one place. It is our hope that the experience will open new vistas into the Rebbe’s vision and .עבודת הקודש recharge us for our This year marks the anniversaries of two important dates in Chabad history: and the 70th anniversary of Hayom Yom’s שנת המאתיים להסתלקות כ״ק אדמו״ר הזקן first printing. In accordance with the message of those two auspicious events, the theme of this year’s Kinus highlights the need to use every moment to its every day brings – יום ליום יביע אומר - fullest. Dovid Hamelech writes in Tehilim its own unique message and mission. -

Fall 5775/2014 • Issue 29

FALL 5775/2014 • ISSUE 29 A PUBLICATION OF THE MONTREAL TORAH CENTER BAIS MENACHEM CHABAD LUBAVITCH JOANNE AND JONATHAN GURMAN COMMUNITY CENTER • LOU ADLER SHUL BAIS MENACHEM CHABAD LUBAVITCH Gleanings from the book A Vision of Love SEEDS OF WISDOM Based on personal encounters with the Rebbe a A young woman turned to the Rebbe for his advice. by MENDEL KALMENSON She was contemplating marriage to a young man whose level of Jewish observance was quite different from hers. Did the Rebbe think their relationship was viable? a "Before a couple decides to get married," the Rebbe explained, "the man must have a real understanding of what the woman wants most in her life, and the woman must have a real understanding of what the man wants most in his life. Each must know the other's vision for his or her life, and support it one hundred percent. a "They don't necessarily need to share the exact same vision for their individual lives, but they must genuinely desire that the other person achieve his or her goals. a "When a couple has this bond, then their marriage will be a healthy one." a You don't need to be on the same page, but you should be reading from the same book. MONTREAL TORAH CENTER BAIS MENACHEM CHABAD LUBAVITCH Joanne and Jonathan Gurman Community Center • Lou Adler Shul The Kenny Chankowsky Memorial Torah Library INDEX The Michael Winterstein Digital Learning Center Rabbi Moishe New Rabbi Itchy Treitel Editorial . .3 Attention à l'angle mort ! . .23 Nechama New Pre-School & Day Camp Director MTC’s Sponsors of the Day .