1 Popular Shakespeares

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Jude Akuwudike

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Jude Akuwudike Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian Smyth +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Role Director Production Company Delroy Grant (The Night MANHUNT Marc Evans ITV Studios Stalker) PLEBS Agrippa Sam Leifer Rise Films/ITV2 MOVING ON Dr Bello Jodhi May LA Productions/BBC THE FORGIVING EARTH Dr Busasa Hugo Blick BBC/Netflix CAROL AND VINNIE Ernie Dan Zeff BBC IN THE LONG RUN Uncle Akie Declan Lowney Sky KIRI Reverend Lipede Euros Lyn Hulu/Channel 4 THE A WORD Vincent Sue Tully Fifty Fathoms/BBC DEATH IN PARADISE Series 6 Tony Simon Delaney Red Planet/BBC CHEWING GUM Series 2 Alex Simon Neal Retort/E4 FRIDAY NIGHT DINNER Series 4 Custody Sergeant Martin Dennis Channel 4 FORTITUDE Series 2 & 3 Doctor Adebimpe Hettie Macdonald Tiger Aspect/Sky Atlantic LUCKY MAN Doctor Marghai Brian Kelly Carnival Films/Sky 1 UNDERCOVER Al James Hawes BBC CUCUMBER Ralph Alice Troughton Channel 4 LAW & ORDER: UK Marcus Wright Andy Goddard Kudos Productions HOLBY CITY Marvin Stewart Fraser Macdonald BBC Between Us (pty) Ltd/Precious THE NO.1 LADIES DETECTIVE AGENCY Oswald Ranta Charles Sturridge Films MOSES JONES Matthias Michael Offer BBC SILENT WITNESS Series 11 Willi Brendan Maher BBC BAD GIRLS Series 7 Leroy Julian Holmes Shed Productions for ITV THE LAST DETECTIVE Series 3 Lemford Bradshaw David Tucker Granada HOLBY CITY Derek Fletcher BBC ULTIMATE FORCE Series 2 Mr Salmon ITV SILENT WITNESS: RUNNING ON -

1 BBC Four Biopics

BBC Four biopics: Lessons in Trashy Respectability The broadcast of Burton and Taylor in July 2013 marked the end of a decade- long cycle of feature-length biographical dramas transmitted on BBC Four, the niche arts and culture digital channel of the public service broadcaster. The subjects treated in these biopics were various: political figures, famous cooks, authors of popular literature, comedians and singers. The dramas focused largely on the unhappy or complex personal lives of well-loved figures of British popular culture. From the lens of the 21st century, these dramas offered an opportunity for audiences to reflect on the culture and society of the 20th century, changing television’s famous function of ‘witness’ to one of ‘having witnessed’ and/or ‘remembering’ (Ellis, 2000). The programmes function as nostalgia pieces, revisiting personalities familiar to the anticipated older audience of BBC Four, working in concert with much of the archive and factual content on the digital broadcaster’s schedules. However, by revealing apparent ‘truths’ that reconfigure the public images of the figures they narrate, these programmes also undermine nostalgic impulses, presenting conflicting interpretations of the recent past. They might equally be seen as impudent incursions onto the memory of the public figures, unnecessarily exposing the real-life subjects to censure, ridicule or ex post facto critical judgement. Made thriftily on small budgets, the films were modest and spare in visual style but were generally well received critically, usually thanks to writerly screenplays and strong central performances. The dramas became an irregular but important staple of the BBC Four schedule, furnishing the channel with some of their highest ratings in a history chequered by low audience numbers. -

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Richard Cant

Richard Cant Photo: Wolf Marloh Stage 2019, Stage, Quentin Crisp, AFTER EDWARD, Globe Theatre, London, Brendan O'Hea 2019, Stage, Earl of Lancaster, EDWARD THE SECOND, Globe Theatre, London, Nick Bagnall 2018, Stage, Jeremy Crowther, MAYDAYS, Royal Shakespeare Company, Owen Horsley 2017, Stage, DeStogumber/ Poulengey, SAINT JOAN, Donmar, Josie Rourke 2016, Stage, One, STELLA, LIFT/Brighton Festival, Neil Bartlett 2015, Stage, Aegeus, MEDEA, Almeida, Rupert Goold 2015, Stage, Bernie, MY NIGHT WITH REG, Donmar Warehouse/ Apollo Theatre, Rob Hastie 2015, Stage, Tudor/Male Guard/Assistant, THE TRIAL, The Young Vic, Richard Jones 2013, Stage, Friedrich Muller, WAR HORSE, NT at New London Theatre, Alex Sims, Kathryn Ind 2010, Stage, Page of Herodias, SALOME, Headlong, Jamie Lloyd 2008, Stage, Thersites, TROILUS AND CRESSIDA, Cheek by Jowl, Declan Donnellan 2007, Stage, Pisanio, CYMBELINE, Cheek by Jowl, Declan Donnellan 2002, Stage, Lord Henry, ORIGINAL SIN, Sheffield Crucible Theatre, Peter Gill 2000, Stage, Darren, OTHER PEOPLE, Royal Court Theatre, Dominic Cooke 2000, Stage, Brian/Javid, PERA PALAS, Gate, Sacha Wares 2000, Stage, SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER, New Kent Opera, Hettie McDonald 2000, Stage, Sparkish, THE COUNTRY WIFE, Sheffield Crucible Theatre, Michael Grandage 1999, Stage, Prior, ANGELS IN AMERICA, Library, Manchester, Roger Haines 1997, Stage, Arviragus, CYMBELINE, Royal Shakespeare Company, Adrian Noble 1997, Stage, Rosencrantz, HAMLET, RSC, Matthew Warchus 1997, Stage, Balthasar, MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING, RSC, Michael Boyd 1996, Stage, -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 19 – 25 August 2017 Page 1 of 8

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 19 – 25 August 2017 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 19 AUGUST 2017 Read by Robert Glenister monarchy and giving a glimpse into the essential ingredients of a Written by Sarah Dunant successful sovereign. SAT 00:00 Bruce Bedford - The Gibson (b007js93) Abridged by Eileen Horne In this programme, Will uses five objects to investigate a pivotal Episode 5Saul and Elise make a grim discovery in the nursing Produced by Clive Brill aspect of the art of monarchy - the projection of magnificence. An home. Time-hopping thriller with Robert Glenister and Freddie A Pacificus production for BBC Radio 4. idea as old as monarchy itself, magnificence is the expression of Jones. SAT 02:15 Me, My Selfie and I: Aimee Fuller©s Generation power through the display of wealth and status. Will©s first object SAT 00:30 Soul Music (b04nrw25) Game (b06172qq) unites our current Queen with George III; the Gold State Coach, Series 19, A Shropshire Lad"Into my heart an air that kills Episode 5In the final part of her exploration of the selfie which has been used for coronations since 1821. Built for George From yon far country blows: phenomenon, snowboarder Aimee Fuller describes how she will III in 1762, it reflects Britain©s new found glory in its richly gilded What are those blue remembered hills, be using social media as she sets out to compete for a place at the carvings and painted panels...but the glory was to be short lived. What spires, what farms are those? next Winter Olympics. -

The Nation's Matron: Hattie Jacques and British Post-War Popular Culture

The Nation’s Matron: Hattie Jacques and British post-war popular culture Estella Tincknell Abstract: Hattie Jacques was a key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, condensing a range of contradictions around power, desire, femininity and class through her performances as a comedienne, primarily in the Carry On series of films between 1958 and 1973. Her recurrent casting as ‘Matron’ in five of the hospital-set films in the series has fixed Jacques within the British popular imagination as an archetypal figure. The contested discourses around nursing and the centrality of the NHS to British post-war politics, culture and identity, are explored here in relation to Jacques’s complex star meanings as a ‘fat woman’, ‘spinster’ and authority figure within British popular comedy broadly and the Carry On films specifically. The article argues that Jacques’s star meanings have contributed to nostalgia for a supposedly more equitable society symbolised by socialised medicine and the feminine authority of the matron. Keywords: Hattie Jacques; Matron; Carry On films; ITMA; Hancock’s Half Hour; Sykes; star persona; post-war British cinema; British popular culture; transgression; carnivalesque; comedy; femininity; nursing; class; spinster. 1 Hattie Jacques (1922 – 1980) was a gifted comedienne and actor who is now largely remembered for her roles as an overweight, strict and often lovelorn ‘battle-axe’ in the British Carry On series of low- budget comedy films between 1958 and 1973. A key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, Hattie Jacques’s star meanings are condensed around the contradictions she articulated between power, desire, femininity and class. -

Going Greek Auction Action Sea Food

THE GRISTLE, P.06 + BOTTOMS UP, P.12 + FILM SHORTS, P.20 c a s c a d i a REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA WHATCOM SKAGIT SURROUNDING AREAS 06-19-2019* • ISSUE:* 25 • V.14 AUCTION ACTION GOING GREEK VAN GOGH FOR SYLVIA CENTER’S THE YOUTH SUMMER REP P.14 P.13 SEA FOOD DINNER IN THE BAY P.26 Summer Solstice Music Festival P.16 A brief overview of this GET OUT 26 Longest Day 10K: 7pm, Fairhaven Village Green FOOD week’s happenings FOOD THISWEEK Ferndale Farmers Market: 2pm-6pm, LaBounty Drive 21 Bright Night Market: 5pm-11pm, Aslan Depot SATURDAY [06.22.19] B-BOARD ONSTAGE Visiting Mr. Green: 2pm Bellingham Theatre Guild 20 Briseis: 7:30pm, Maritime Heritage Park Nunsense: 7:30pm, Bellingham Theatre Guild FILM Writer’s Block: 7:30pm, Upfront Theatre James and the Giant Peach: 7:30pm, Anacortes Community Theatre 16 All are welcome PainProv: 9:30pm, Upfront Theatre MUSIC when the DANCE Bellingham Stepsisters, a Dance Story: 2pm and 7pm, Sylvia 14 Center Rubies: 7pm, Mount Baker Theatre ART Roller Betties An Evening of Belly Dance: 7pm, Firehouse Arts host a semifinal & Events Center 13 On Trend: 7pm, McIntyre Hall roller derby bout STAGE FILM Sat., June 22 Dudestock: 7pm, Lincoln Theatre, Mount Vernon Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: Dusk, Fairhaven Village 12 at the Whatcom Green Community College COMMUNITY GET OUT Green Home Tour: 10am-5pm, seven locales Pavilion. throughout Whatcom County 10 GET OUT Padden Triathlon: 8am, Lake Padden Park March Point Run: 9am, Andeavor Refinery, WORDS Anacortes NICK SADIGH PHOTOGRAPHY SADIGH NICK Rose Festival: 9am-4pm, Christianson’s Nursery, 8 Mount Vernon WEDNESDAY [06.19.19] Fun Fly Kite Day: 10am-4pm, Marine Park, Blaine Roller Betties: 5pm, Whatcom Community College CURRENTS ONSTAGE Pavilion Bard on the Beach: Through September, Vanier Park, 6 Vancouver B.C. -

Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films

Gesticulated Shakespeare: Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Rebecca Collins, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Alan Woods, Advisor Janet Parrott Copyright by Jennifer Rebecca Collins 2011 Abstract The purpose of this study is to dissect the gesticulation used in the films made during the silent era that were adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays. In particular, this study investigates the use of nineteenth and twentieth century established gesture in the Shakespearean film adaptations from 1899-1922. The gestures described and illustrated by published gesture manuals are juxtaposed with at least one leading actor from each film. The research involves films from the experimental phase (1899-1907), the transitional phase (1908-1913), and the feature film phase (1912-1922). Specifically, the films are: King John (1899), Le Duel d'Hamlet (1900), La Diable et la Statue (1901), Duel Scene from Macbeth (1905), The Taming of the Shrew (1908), The Tempest (1908), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1909), Il Mercante di Venezia (1910), Re Lear (1910), Romeo Turns Bandit (1910), Twelfth Night (1910), A Winter's Tale (1910), Desdemona (1911), Richard III (1911), The Life and Death of King Richard III (1912), Romeo e Giulietta (1912), Cymbeline (1913), Hamlet (1913), King Lear (1916), Hamlet: Drama of Vengeance (1920), and Othello (1922). The gestures used by actors in the films are compared with Gilbert Austin's Chironomia or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery (1806), Henry Siddons' Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to The English Drama: From a Work on the Subject by M. -

The Mousetrap Tour

PRESS RELEASE – Friday 12 April 2019 WWW.MOUSETRAPONTOUR.COM Adam Spiegel and Stephen Waley-Cohen present THE MOUSETRAP TOUR SUSAN PENHALIGON JOINS THE UK TOUR OF AGATHA CHRISTIE’S RECORD-BREAKING MURDER MYSTERY THE MOUSETRAP AS MRS BOYLE FROM 15 JULY 2019 - 16 NOVEMBER 2019 THE LEGENDARY WHODUNNIT CONTINUES ON AN EXTENSIVE TOUR OF THE UK WITH FURTHER DATES TO BE ANNOUNCED THROUGHOUT 2020 THE RECORD-BREAKING RUN CONTINUES IN THE WEST END AT THE ST MARTIN’S THEATRE Television star Susan Penhaligon (Bouquet of Barbed Wire, A Fine Romance, Emmerdale) will join the cast of Agatha Christie’s legendary whodunnit as Mrs Boyle this summer as it continues on a major UK tour. Susan Penhaligon will take over the role from Gwyneth Strong (Only Fools and Horses) from 15 July at Malvern Festival Theatre through to and including Birmingham Alexandra Theatre until 16 November 2019. Directed by Gareth Armstrong, the timeless thriller returned to the road by popular demand in January 2019 and has been earning standout reviews from critics and public alike as it continues to visit more than 40 venues, travelling the length and breadth of the country. The Mousetrap has been delighting audiences for 67 years and the identity of the murderer remains theatre’s best kept secret. This is the second major national tour of the smash hit murder mystery following a record-breaking 60th anniversary debut in 2012. Susan Penhaligon (Mrs Boyle) is well-known for her role in the ITV drama Bouquet of Barbed Wire, and for playing Helen Barker in the ITV sitcom A Fine Romance. -

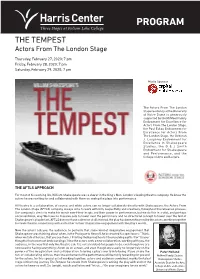

PROGRAM the TEMPEST Actors from the London Stage

PROGRAM THE TEMPEST Actors From The London Stage Thursday, February 27, 2020; 7 pm Friday, February 28, 2020; 7 pm Saturday, February 29, 2020; 7 pm Media Sponsor The Actors From The London Stage residency at the University of Notre Dame is generously supported by the McMeel Family Endowment for Excellence for Actors From The London Stage, the Paul Eulau Endowment for Excellence for Actors From The London Stage, the Deborah J. Loughrey Endowment for Excellence in Shakespeare Studies, the D & J Smith Endowment for Shakespeare and Performance, and the College of Arts and Letters. THE AFTLS APPROACH For most of his working life, William Shakespeare was a sharer in the King’s Men, London’s leading theatre company. He knew the actors he was writing for and collaborated with them on seeing the plays into performance. All theatre is a collaboration, of course, and while actors can no longer collaborate directly with Shakespeare, the Actors From The London Stage (AFTLS) company always aims to work with him, respectfully and creatively, throughout the rehearsal process. Our company’s aim is to make his words exert their magic and their power in performance, but we do this in a vital, and perhaps unconventional, way. We have no massive sets to tower over the performers and no directorial concept to tower over the text of Shakespeare’s play. In fact, AFTLS does not have a director at all; instead, the play has been rehearsed by the actors, working together to create theatre, cooperating with each other in their imaginative engagement with the play’s words.