Newsletter 24.2 Fall 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: June 5, 2019 MEDIA CONTACTS: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] J. PAUL GETTY TRUST BOARD OF TRUSTEES ELECTS DR. DAVID L. LEE AS CHAIR Dr. David L. Lee has served on the Board since 2009; he begins his four-year term as chair on July 1 LOS ANGELES—The Board of Trustees of the J. Paul Getty Trust today announced it has elected Dr. David L. Lee as its next chair of the Board. “We are delighted that Dr. Lee will lead the Getty Board of Trustees as we embark on many exciting initiatives,” said Getty President James Cuno. “Dr. Lee’s involvement with the international community, his experience in higher education and philanthropy, and his strong financial acumen has served the Getty well. We look forward to his leadership.” Dr. Lee was appointed to the Getty Board of Trustees in 2009. Dr. Lee will serve a four-year term as chair of the 15-member group that includes leaders in art, education, and business who volunteer their time and expertise on behalf of the Getty. “Through its extensive research, conservation, exhibition and education programs, the Getty’s work has made a powerful impact not only on the Los Angeles region, but around the world,” Dr. Lee said. “I am honored to be part of such a generous, inspiring organization that makes a lasting difference and is a source of great pride for our community.” The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 Dr. -

Press Image Sheet

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: September 17, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] GETTY TO DEVOTE $100 MILLION TO ADDRESS THREATS TO THE WORLD’S ANCIENT CULTURAL HERITAGE Global initiative will enlist partners to raise awareness of threats and create effective conservation and education strategies Participants in the 2014 Mosaikon course Conservation and Management of Archaeo- logical Sites with Mosaics conduct a condition survey exercise of the Achilles Mosaic at the Paphos Archeological Park, Paphos, Cyprus. Continued work at Paphos will be undertaken as part of Ancient Worlds Now. Los Angeles – The J. Paul Getty Trust will embark on an unprecedented and ambitious $100- million, decade-long global initiative to promote a greater understanding of the world’s cultural heritage and its universal value to society, including far-reaching education, research, and conservation efforts. The innovative initiative, Ancient Worlds Now: A Future for the Past, will explore the interwoven histories of the ancient worlds through a diverse program of ground-breaking The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 scholarship, exhibitions, conservation, and pre- and post- graduate education, and draw on partnerships across a broad geographic spectrum including Asia, Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and Europe. “In an age of resurgent populism, sectarian violence, and climate change, the future of the world’s common heritage is at risk,” said James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. -

Getty and Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage Announce Major Enhancements to Ghent Altarpiece Website

DATE: August 20, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE IMAGES OF THE RESTORED ADORATION OF THE LAMB AND MORE: GETTY AND ROYAL INSTITUTE FOR CULTURAL HERITAGE ANNOUNCE MAJOR ENHANCEMENTS TO GHENT ALTARPIECE WEBSITE Closer to Van Eyck offers a 100 billion-pixel view of the world-famous altarpiece, to be enjoyed from home http://closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be/ The Lamb of God on the central panel, from left to right: before restoration (with the 16th-century overpaint still present), during restoration (showing the van Eycks’ original Lamb from 1432 before retouching), after retouching (the final result of the restoration) LOS ANGELES AND BRUSSELS – Since 2012, the website Closer to Van Eyck has made it possible for millions around the globe to zoom in on the intricate, breathtaking details of the Ghent Altarpiece, one of the most celebrated works of art in the world. More than a quarter million people have taken advantage of the opportunity so far in 2020, and website visitorship has increased by 800% since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring the potential for modern digital technology to increase access to masterpieces from all eras and learn more about them. The Getty and the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA, Brussels, Belgium), in collaboration with the Gieskes Strijbis Fund in Amsterdam, are giving visitors even more ways to explore this monumental work of art from afar, with the launch today of a new version of the site that includes images of recently restored sections of the paintings as well as new videos and education materials. Located at St. -

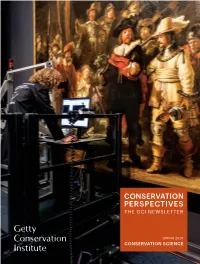

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES THE GCI NEWSLETTER SPRING 2020 CONSERVATION SCIENCE A Note from As this issue of Conservation Perspectives was being prepared, the world confronted the spread of coronavirus COVID-19, threatening the health and well-being of people across the globe. In mid-March, offices at the Getty the Director closed, as did businesses and institutions throughout California a few days later. Getty Conservation Institute staff began working from home, continuing—to the degree possible—to connect and engage with our conservation colleagues, without whose efforts we could not accomplish our own work. As we endeavor to carry on, all of us at the GCI hope that you, your family, and your friends, are healthy and well. What is abundantly clear as humanity navigates its way through this extraordinary and universal challenge is our critical reliance on science to guide us. Science seeks to provide the evidence upon which we can, collectively, make decisions on how best to protect ourselves. Science is essential. This, of course, is true in efforts to conserve and protect cultural heritage. For us at the GCI, the integration of art and science is embedded in our institutional DNA. From our earliest days, scientific research in the service of conservation has been a substantial component of our work, which has included improving under- standing of how heritage was created and how it has altered over time, as well as developing effective conservation strategies to preserve it for the future. For over three decades, GCI scientists have sought to harness advances in science and technology Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: to further our ability to preserve cultural heritage. -

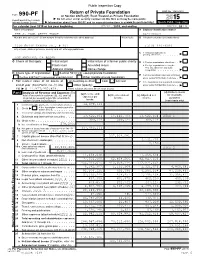

Attach to Your Tax Return. Department of the Treasury Attachment Sequence No

Public Inspection Copy Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2015 or tax year beginning 07/01 , 2015, and ending 06/30, 20 16 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST 95-1790021 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 1200 GETTY CENTER DR., # 401 (310) 440-6040 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here LOS ANGELES, CA 90049 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the Address change Name change 85% test, check here and attach computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: CashX Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part II, col. -

Research Institute Grants

Getty Research Institute Grants Artistic Practice 2011/2012 Theme Year aT The GeTTY research insTiTuTe Artists mobilize a variety of intellectual, organizational, technological, and physical resources to create their work. This scholar year will delve into the ways in which artists receive, work with, and transmit ideas and images in various cultural traditions. At the Getty Research Institute, scholars will pay particular attention to the material manifestations of memory and imagination in the form of sketchbooks, notebooks, pattern books, and model books. How do notes, remarks, written and drawn observations reveal the creative process? In times and places where such media were not in use, what practices were developed to give ideas material form? In the ancient world, artists left traces of their creative process in a variety of media, but many questions remain for scholars in residence at the Getty Villa: What was the role of prototypes such as casts and models; what was their relationship to finished works? How were artists trained and workshops structured? How did techniques and styles travel? An interdisciplinary investigation among art historians and other specialists in the humanities will lead to a richer understanding of artistic practice. HoW To Apply Detailed instructions, application forms, complete theme statement and additional information are available online at www.getty.edu/foundation/apply Address inquiries to: Attn: (Type of Grant) The Getty Foundation 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 800 DeaDline los Angeles, CA 90049-1685 USA phone: 310 440.7374 nov 1 2010 E-mail: [email protected] Academy of fine arts, 1578. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California. -

J. Paul Getty Trust Press Clippings, 1954-2019 (Bulk 1983-2019), Undated

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8r215vp Online items available Finding aid for the J. Paul Getty Trust Press Clippings, 1954-2019 (bulk 1983-2019), undated Nancy Enneking, Rebecca Fenning, Kyle Morgan, and Jennifer Thompson Finding aid for the J. Paul Getty IA30017 1 Trust Press Clippings, 1954-2019 (bulk 1983-2019), undated Descriptive Summary Title: J. Paul Getty Trust press clippings Date (inclusive): 1954-2019, undated (bulk 1983-2019) Number: IA30017 Physical Description: 43.35 Linear Feet(55 boxes) Physical Description: 2.68 GB(1,954 files) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Institutional Records and Archives 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The records comprise press clippings about the J. Paul Getty Trust, J. Paul Getty Museum, other Trust programs, and Getty family and associates, 1954-2019 (bulk 1983-2019) and undated. The records contain analog and digital files and document the extent to which the Getty was covered by various news and media outlets. Request Materials: To access physical materials at the Getty, go to the library catalog record for this collection and click "Request an Item." Click here for general library access policy . See the Administrative Information section of this finding aid for access restrictions specific to the records described below. Please note, some of the records may be stored off site; advanced notice is required for access to these materials. Language: Collection material is in English Administrative History The J. Paul Getty Trust's origins date to 1953, when J. -

Conservation Perspectives

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES FALL 2020 BUILT HERITAGE CONSERVATION EDUCATION AND TRAINING A Note from It is indisputable that education and training form the foundation of a profession. But as uncon- the Director troversial as that notion is, there is often less consensus within any given profession about what constitutes the best or most essential elements of that education. And in this historic moment of a worldwide pandemic, how—and in what ways—can education and training proceed and be effective? This edition of Conservation Perspectives examines how conservation education and training in built heritage have developed since the mid-twentieth century. Without question there has been exponential growth, providing opportunities for learning that did not exist for earlier generations. But with changing circumstances— including the pandemic and its aftereffects, as well as the reduced availability of resources—new issues and questions arise regarding what the field needs to do to advance in this area. We hope that we can provide some insights into where we need to go by looking back at where we’ve been. In our feature article, Jacqui Goddard, an architect who also teaches heritage conservation at the University of Sydney, charts the development of education in architectural conservation, which began in earnest in the latter half of the twen- tieth century. She notes that despite the rise of accreditation schemes, the divide Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: between individual professions and disciplines and conservation practice has yet to be fully bridged. In another article, my Getty Conservation Institute colleague Jeff Cody describes the GCI’s activities in built heritage conservation training and education from its earliest days to the present. -

Executive Compensation Process

THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NO. 95-1790021 SENIOR MANAGEMENT COMPENSATION Updated March 3, 2015 The Role of the Board of Trustees in Overseeing Senior Management Compensation The full Board of Trustees establishes the terms of the President’s employment and compensation. The Compensation Committee, a standing committee composed of independent members of the Board of Trustees, approves the compensation of the President’s direct reports. Trustees of the J. Paul Getty Trust receive no compensation for their service but are reimbursed for travel expenses incurred in fulfilling their duties as members of the Board. In addition, Trustees are eligible to participate in a matching gift program providing matching gift funds to eligible qualified public charities on a four-to-one basis up to an annual maximum matching amount of $60,000. The J. Paul Getty Trust Senior Management Compensation Policy The goal of the Getty’s compensation process is to pay salaries that are competitive for comparable positions at organizations similar in activities and scope. The performance and compensation of the President and Chief Executive Officer is reviewed and set by the Board of Trustees in executive sessions in the absence of the President and CEO. Compensation decisions regarding direct reports to the President are recommended by the President and CEO to the Compensation Committee for approval. Program Directors and Vice Presidents are eligible to participate in a matching gifts program providing matching gift funds to eligible qualified public charities on a four-to-one basis up to an annual maximum matching amount of $32,000. The Compensation Committee reviews and compares compensation levels for the President and his direct reports with those reported for analogous positions at comparable organizations. -

Susan Steinhauser and Daniel Greenberg

The Getty A WORLD OF ART, RESEARCH, CONSERVATION, AND PHILANTHROPY | Fall 2014 INSIDE THIS ISSUE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The J. Paul Getty Trust is a cultural TABLE OF CONTENTS by James Cuno and philanthropic institution President and CEO, the J. Paul Getty Trust dedicated to critical thinking in the presentation, conservation, and interpretation of the world’s artistic President’s Message 3 legacy. Through the collective and Last year the Getty inaugurated the J. Paul Getty Medal to honor individual work of its constituent New and Noteworthy 4 extraordinary achievement in the fields of museology, art historical programs—Getty Conservation research, philanthropy, conservation, and conservation science. The first Institute, Getty Foundation, J. Paul Lord Jacob Rothschild to Receive Getty Medal 6 recipients were Harold M. Williams and Nancy Englander, who were Getty Museum, and Getty Research chosen for their role in creating the Getty as a global leader in art Institute—it pursues its mission in Los Angeles and throughout the world, Conserving an Ancient Treasure 10 history, conservation, and museum practice. This year we are honoring serving both the general interested Lord Jacob Rothschild OM GBE for his extraordinary leadership and public and a wide range of A Project of Seismic Importance 16 contributions to the arts. professional communities with the In November, we will bestow the J. Paul Getty Medal on Lord Rothschild, conviction that a greater and more WWI: War of Images, Images of War 20 profound sensitivity to and knowledge a most distinguished leader in our field. He has served as chairman of of the visual arts and their many several of the world’s most important art-, architecture-, and heritage- histories is crucial to the promotion Caravaggio and Rubens Together in Vienna 24 related organizations, and is renowned for this dedication to the of a vital and civil society. -

Download Document

The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 400 Tel 310 440 7360 Communications Department Los Angeles, California 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 www.getty.edu [email protected] NEWS FROM THE GETTY FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 2010 GETTY CENTER FACTS • Opened on Dec. 16, 1997 • Welcomed more than 14 million visitors since 1997; about half from outside the region, and half from the greater Los Angeles area. • 550,000 schoolchildren from across the Southland have come on school visits; 378,836 from Title One schools; 171,943 on the Getty’s school bus transportation program. • About 1,300 employees and nearly 900 volunteers and docents work at the site. • The site acquired LEED certification in 2005, recognizing its efforts to optimize energy and water efficiency, minimize waste; improve indoor environment quality; and provide a framework for sustainability • The Getty hires a herd of goats each spring to help clear brush and reduce fire danger on the hillside. • Last year, the J. Paul Getty Trust was nationally recognized by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Transportation as one of the “Best Workplaces for Commuters” for providing excellent commuter benefits to staff. J. Paul Getty Museum • Sixteen percent of the art currently on exhibit in the Museum was personally acquired by J. Paul Getty. • The Museum paintings galleries feature skylights with computer-controlled louvers and a system of warm and cool artificial lights. Programmed to the season and time of day, the computer adjusts the louvers as well as the lights needed to achieve optimal illumination. -more- Page 2 • The J. -

The J. Paul Getty Trust 2007 Report the J

THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST 2007 REPORT THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST 2007 REPORT 4 Message from the Chair 7 Foreword 10 The J. Paul Getty Museum Acquisitions Exhibitions Scholars Councils Patrons Docents & Volunteers 26 The Getty Research Institute Acquisitions Exhibitions Scholars Council 38 The Getty Conservation Institute Projects Scholars 48 The Getty Foundation Grants Awarded 64 Publications 66 Staff 73 Board of Trustees, Offi cers & Directors 74 Financial Information e J. Paul Getty Trust The J. Paul Getty Trust is an international cultural and philanthropic institution that focuses on the visual arts in all their dimensions, recognizing their capacity to inspire and strengthen humanistic values. The Getty serves both the general public and a wide range of professional communities in Los Angeles and throughout the world. Through the work of the four Getty programs–the Museum, Research Institute, Conservation Institute, and Foundation–the Getty aims to further knowledge and nurture critical seeing through the growth and presentation of its collections and by advancing the understanding and preservation of the world’s artistic heritage. The Getty pursues this mission with the conviction that cultural awareness, creativity, and aesthetic enjoyment are essential to a vital and civil society. e J. Paul Getty Trust 3 Message from the Chair e 2007 fi scal year has been a time of progress and accomplishment at the J. Paul Getty Trust. Each of the Getty’s four programs has advanced signifi cant initiatives. Agreements have been reached on diffi cult antiquities claims, and the challenges of two and three years ago have been addressed by the implementation of new policies ensuring the highest standards of governance.