Type Your Uppercase Title Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VVMF Education Guide

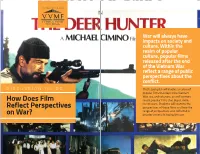

FOUNDERS OF THE WALL ECHOES FROM THE WALL War will always have impacts on society and culture. Within the realm of popular culture, popular films released after the end of the Vietnam War reflect a range of public perspectives about the conflict. DISCUSSION GUIDE This lesson plan will involve a review of popular films that depict the Vietnam War, era, and veterans, as well as more How Does Film recent popular films that depict more recent wars. Students will examine the Reflect Perspectives perspectives of these films and how the range of perspectives was reflected in on War? broader society following the war. Download the Perspectives on War? Reflect Does Film How Accompanying Powerpoint Presentation for use in the classroom > PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 1 Films from Vietnam Ask students to create a list of movies they have seen that have a focus on the Vietnam War, era, or veterans (for a list, see: http://www.vvmf.org/teaching-vietnam). Ask each student to choose a favorite from the list and explain his/her reasoning for why it’s his/her favorite. If a student hasn’t see any—ask him or her to choose one to watch at home. For that movie, ask students to answer the following questions: • What issues are depicted in the movie? • Would you say that the movie takes a position on the war? What evidence supports your answer? • What part or parts of the movie struck you? Why? • What do you think someone who had no background on the Vietnam War or era would take away about it from this movie? PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 2 Vietnam in Media Ask students to poll 10 of their siblings, friends, or even parents: What are the top two NOTE TO sources from which they have any understanding of the TEACHER Vietnam War and era? Place a tally mark beside each response. -

Rambo: Last Blood Production Notes

RAMBO: LAST BLOOD PRODUCTION NOTES RAMBO: LAST BLOOD LIONSGATE Official Site: Rambo.movie Publicity Materials: https://www.lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/rambo-last-blood Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Rambo/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/RamboMovie Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/rambomovie/ Hashtag: #Rambo Genre: Action Rating: R for strong graphic violence, grisly images, drug use and language U.S. Release Date: September 20, 2019 Running Time: 89 minutes Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Paz Vega, Sergio Peris-Mencheta, Adriana Barraza, Yvette Monreal, Genie Kim aka Yenah Han, Joaquin Cosio, and Oscar Jaenada Directed by: Adrian Grunberg Screenplay by: Matthew Cirulnick & Sylvester Stallone Story by: Dan Gordon and Sylvester Stallone Based on: The Character created by David Morrell Produced by: Avi Lerner, Kevin King Templeton, Yariv Lerner, Les Weldon SYNOPSIS: Almost four decades after he drew first blood, Sylvester Stallone is back as one of the greatest action heroes of all time, John Rambo. Now, Rambo must confront his past and unearth his ruthless combat skills to exact revenge in a final mission. A deadly journey of vengeance, RAMBO: LAST BLOOD marks the last chapter of the legendary series. Lionsgate presents, in association with Balboa Productions, Dadi Film (HK) Ltd. and Millennium Media, a Millennium Media, Balboa Productions and Templeton Media production, in association with Campbell Grobman Films. FRANCHISE SYNOPSIS: Since its debut nearly four decades ago, the Rambo series starring Sylvester Stallone has become one of the most iconic action-movie franchises of all time. An ex-Green Beret haunted by memories of Vietnam, the legendary fighting machine known as Rambo has freed POWs, rescued his commanding officer from the Soviets, and liberated missionaries in Myanmar. -

Fighters and Fathers: Managing Masculinity in Contemporary Boxing Cinema

Fighters and Fathers: Managing Masculinity in Contemporary Boxing Cinema JOSH SOPIARZ In Antoine Fuqua’s film Southpaw (2015), just as Jake Gyllenhaal’s character Billy Hope attempts suicide by crashing his luxury sedan into a tree in the front yard, his ten-year-old daughter, Leila, sends him a text message asking: “Daddy. Where are you?” (00:46:04). Her answer comes seconds later when, upon hearing a crash, she finds her father in a heap concussed and bleeding badly on the white marble floor of their home’s entryway. Upon waking, Billy’s first and only concern is Leila. Hospital workers, in an effort to calm him, tell Billy that Leila is safe “with child services” (00:48:08-00:48:10) This news does not comfort Billy. Instead, upon learning that Leila is in the state’s custody, the former light heavyweight champion of the world, with face bloodied and muscles rippling, makes his most concerted effort to get up and leave—presumably, to find his daughter. Before he can rise, however, a doctor administers a large dose of sedative and the heretofore unrestrainable Billy fades into unconsciousness as the scene ends. Leila’s simple question—“Daddy. Where are you?”—is central not only to Southpaw but is also relevant for most major boxing films of the 21st century.1 This includes Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby (2004), David O. Russell’s The Fighter (2010), Ryan Coogler’s Creed (2015), Jonathan Jakubowic’s Hands of Stone (2016), and Stephen Caple, Jr.’s Creed II (2018). These films establish fighter/trainer relationships as alternatives to otherwise biological or “traditional” father/son relationships. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

The Use of Music in the Cinematic Experience

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 2019 The seU of Music in the Cinematic Experience Sarah Schulte Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Schulte, Sarah, "The sU e of Music in the Cinematic Experience" (2019). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 780. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/780 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUND AND EMOTION: THE USE OF MUSIC IN THE CINEMATIC EXPERIENCE A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky Univeristy By Sarah M. Schulte May 2019 ***** CE/T Committee: Professor Matthew Herman, Advisor Professor Ted Hovet Ms. Siera Bramschreiber Copyright by Sarah M. Schulte 2019 Dedicated to my family and friends ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the help and support of so many people. I am incredibly grateful to my faculty advisor, Dr. Matthew Herman. Without your wisdom on the intricacies of composition and your constant encouragement, this project would not have been possible. To Dr. Ted Hovet, thank you for believing in this project from the start. I could not have done it without your reassurance and guidance. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

ALLISA SWANSON Costume Designer

ALLISA SWANSON Costume Designer https://www.allisaswanson.com/ Selected Television: FIREFLY LANE (Pilot, S1&2) – Netflix / Brightlight Pictures – Maggie Friedman, creator TURNER & HOOCH (Pilot, S1) – 20th Century Fox / Disney+ – Matt Nix, writer – McG, pilot dir. ALIVE (Pilot) – CBS Studios – Uta Briesewitz, director ANOTHER LIFE (Pilot, S1) – Netflix / Halfire Entertainment – Aaron Martin, creator ONCE UPON A TIME (S7 eps. 716-722) – Disney/ABC TV – Edward Kitsis & Adam Horowitz, creators *NOMINATED, Excellence in Costume Design in TV – Sci-Fi/Fantasy - CAFTCAD Awards THE 100 (S3 + S4) – Alloy Entertainment / Warner Bros. / The CW – Jason Rothenberg, creator DEAD OF SUMMER (Pilot, S1) Disney / ABC / Freeform – Ian Goldberg, Adam Horowitz & Eddy Kitsis, creators MORTAL KOMBAT: LEGACY (Mini Series) – Warner Bros. – Kevin Tancharoen, director BEYOND SHERWOOD (TV Movie) – SyFy / Starz – Peter DeLuise, director KNIGHTS OF BLOODSTEEL (Mini-Series) – SyFy / Reunion Pictures – Phillip Spink, director SEA BEAST (TV Movie) – SyFy / NBC Universal TV – Paul Ziller, director EDGEMONT (S1 - S5) – CBC / Water Street Pictures / Fox Family Channel – Ian Weir, creator Selected Features: COFFEE & KAREEM – Netflix / Pacific Electric Picture Company – Michael Dowse, director GOOD BOYS (Addt’l Photo. )– Universal / Good Universe / Point Grey Pictures – Gene Stupnitsky, dir. DARC – Netflix / JRN Productions – Nick Powell, director THE UNSPOKEN – Lighthouse Pictures / Paladin – Sheldon Wilson, director THE MARINE: HOMEFRONT – WWE Studios – Scott Wiper, director ICARUS/THE KILLING MACHINE – Cinetel Films – Dolph Lundgren, director SPACE BUDDIES – Walt Disney Home Entertainment – Robert Vince, director DANCING TREES – NGN Productions – Anne Wheeler, director THE BETRAYED – MGM – Amanda Gusack, director SNOW BUDDIES – Walt Disney Home Entertainment – Robert Vince, director BLONDE & BLONDER – Rigel Entertainment – Bob Clark, director CHESTNUT: HERO OF CENTRAL PARK – Miramax / Keystone Entertainment – Robert Vince, dir. -

Tv Pg 6 3-2.Indd

6 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, March 2, 2009 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening March 2, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC Lost Lost 20/20 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles The Good Wife Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX American Idol Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Criminal Minds CSI: Miami CSI: Miami Criminal Minds Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC To-Mockingbird To-Mockingbird Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather Wild Recon Madman of the Sea Wild Recon Untamed and Uncut Madman Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET National Security Vick Tiny-Toya The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show Security Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Smarter Smarter Extreme-Home O Brother, Where Art 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY S. -

Introduction Ronald Reagan’S Defining Vision for the 1980S— - and America

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Ronald Reagan’s Defining Vision for the 1980s— -_and America There are no easy answers, but there are simple answers. We must have the courage to do what we know is morally right. ronald reagan, “the speech,” 1964 Your first point, however, about making them love you, not just believe you, believe me—I agree with that. ronald reagan, october 16, 1979 One day in 1924, a thirteen-year-old boy joined his parents and older brother for a leisurely Sunday drive roaming the lush Illinois country- side. Trying on eyeglasses his mother had misplaced in the backseat, he discovered that he had lived life thus far in a “haze” filled with “colored blobs that became distinct” when he approached them. Recalling the “miracle” of corrected vision, he would write: “I suddenly saw a glori- ous, sharply outlined world jump into focus and shouted with delight.” Six decades later, as president of the United States of America, that extremely nearsighted boy had become a contact lens–wearing, fa- mously farsighted leader. On June 12, 1987, standing 4,476 miles away from his boyhood hometown of Dixon, Illinois, speaking to the world from the Berlin Wall’s Brandenburg Gate, Ronald Wilson Reagan em- braced the “one great and inescapable conclusion” that seemed to emerge after forty years of Communist domination of Eastern Eu- rope. “Freedom leads to prosperity,” Reagan declared in his signature For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. -

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

Reagan's Victory

Reagan’s ictory How HeV Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison Foreword by William J. Bennett Reagan’s Victory: How He Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison 1 FOREWORD By William J. Bennett Ronald Reagan always called me on my birthday. Even after he had left the White House, he continued to call me on my birthday. He called all his Cabinet members and close asso- ciates on their birthdays. I’ve never known another man in public life who did that. I could tell that Alzheimer’s had laid its firm grip on his mind when those calls stopped coming. The President would have agreed with the sign borne by hundreds of pro-life marchers each January 22nd: “Doesn’t Everyone Deserve a Birth Day?” Reagan’s pro-life convic- tions were an integral part of who he was. All of us who served him knew that. Many of my colleagues in the Reagan administration were pro-choice. Reagan never treat- ed any of his team with less than full respect and full loyalty for that. But as for the Reagan administration, it was a pro-life administration. I was the second choice of Reagan’s to head the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). It was my first appointment in a Republican administration. I was a Democrat. Reagan had chosen me after a well-known Southern historian and literary critic hurt his candidacy by criticizing Abraham Lincoln. My appointment became controversial within the Reagan ranks because the Gipper was highly popular in the South, where residual animosities toward Lincoln could still be found. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ...................................................................................................................................