Spatial Solutions for Healing in Marginalized Communities: a Case Study on the Gullah/Geechee People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

South Carolina Day by Day by Day Carolina South

Family Literacy Activity Calendar Activity Literacy Family South Carolina Day by Day by Day Carolina South This project is made possible by a grant from the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services. 1500 Senate Street PO Box 11469, Columbia, SC 29211 Telephone: 803-734-8666 http://www.statelibrary.sc.gov The South Carolina State Library is a national model for innovation, collaboration, leadership and effectiveness. It is the keystone in South Carolina's intellectual landscape. Dear Parents, Guardians, and Caregivers: South Carolina Day by Day The South Carolina State Library is proud to introduce the South Carolina Day by Day Family Literacy Activity Day by Day Calendar. You will be excited to watch your child open Oh let's see up to a whole new world through books, reading, and arts and crafts. The activities that fill this calendar are What does the calendar say? selected to support the areas of learning that should help your child become ready for school and ready for We can practice reading reading. Our goal is to help provide you with the tools Learn about healthy eating that make spending time together easy and fun, while at We're Carolina dreaming the same time serving as a guide for learning new things about our state and our world. In addition to suggesting Every day activities using materials found in your home, we provide Now more than at any other time, our children need to lists of books and music which you can find at your local be exposed to the power of literature as they begin their Day by Day library, along with many other educational resources. -

Digital Collections

SOUTH CAROLINA MUSICIAN Volume XLIX-A April 1997 «*"»• Number 2 "A teacher affects eternity; he can never tell where his influence stops" —Henry Adams SCMEA HALL OF FAME //7trod\\vx*§. Carolina Music, LLC. South Carolina's School Band Specialist Featuring: • All instruments complet e with case, accessories, and music stand • All instruments educ;ato r approved • In-house qualified b«an d instrument repair technician • All school visits by (Carolin a Music's representatives are made by appointment only so class time is never interrupted • To guarantee you th<5 best service possible, all Carolina Music representatives are |professiona l educators and musicians who take a personal inter est in each school they serve. Jan Reeves Ross Kennedy President Vice President (803)851-1700 Columbia Regional (888) 222-7654 Operations (803)551-0006 (888) 234-7654 Greg Smith Vice President Carol na Charleston Regional 1103 North Main Street Operations Summerville, SC 29483 Muse (803)851-1700 FAX (803) 851-1035 (888) 222-7654 0 APRIL 1997 WHKEH "THE MUSIC EDUCATOR'S CHOICE" SCHOOL BAND/ORCHESTRA HEADQUARTERS NATIONAL WATS: 1 (800) 922-8824 Large Inventory of Band Affiliate Stores: and Orchestra Instruments/ Accessories Mt. Pleasant TOWN & COUNTRY MUSIC Educational Representatives 849-7732 Greenville 292-2920 Union Spartanburg 574-9326 SIGHT & SOUND Rock Hill 328-9588 427-3262 Florence 665-2240 Hampton 943-4909 Simpsonville THE MUSIC STORE 963-8797 Beaufort SON SHINE MUSIC 522-1222 Conway Surfside Beach Greenwood CHESTNUT MANDOLINS HAGLEY MUSIC NEWELL'S MUSIC 248-5399 238-8400 223-5757 S. C. MUSICIAN JUPITER otuiama xtraordinary new structural innovations give the Jupiter 500 Series flute unprecedented stability .. -

Legislative Update

South Carolina House of Representatives Legislative Update David H. Wilkins, Speaker of the House f S. C. STATE LIB ARY .MAR1. 3 20m STATE DOCUMENTS Vol. 18 March 6, 2001 No. 09 CONTENTS Week in Review ........................................................... 02 House Committee Action ............................................... 08 Bills Introduced in the House This Week ........................... 13 OFFICE OF RESEARCH Room 213, Blatt Building, P.O. Box 11867, Columbia, S.C. 29211, (803) 734-3230 Legislative Update, March 6, 2001 WEEK IN REVIEW HOUSE The House of Representatives amended H.3144 and sent the bill to the Senate. The legislation amends the State Ethics Act, making several revisions that impact CAMPAIGN FINANCE AND LOBBYING of the General Assembly: • The legislation provides for new limitations on initiatives to influence the outcome of measures placed on the ballot to be voted on by the state's electors. Under this bill, the term "ballot measure committee" is defined as (a) an association, club, an organization, or a group of persons which, to influence the outcome of a ballot measure, receives contributions or makes expenditures in excess of $2,500 in the aggregate during an election cycle; (b) a person, other than an individual, who, to influence the outcome of a ballot measure makes contributions aggregating at least $50,000 during an election cycle to, or at least at the request of, a ballot measure committee; or (c) a person, other than an individual, who makes independent expenditures aggregating $2,500 or more during an election cycle. • This bill requires a ballot measure committee, except an out-of-state committee, which receives or expends more than $2,500 in the aggregate during an election cycle to influence the outcome of a ballot measure to file a statement of organization. -

South Carolina Our Amazing Coast

South Carolina Our Amazing Coast SO0TB CARO LINA REGIONS o ..-- -·--C..,..~.1.ulrt..l• t -·- N O o.u. (South Carolina Map, South Carolina Aquarium’s Standards-based Curriculum, http://scaquarium.org) Teacher Resources and Lesson Plans Grades 3-5 Revised for South Carolina Teachers By Carmelina Livingston, M.Ed. Adapted from GA Amazing Coast by Becci Curry *Lesson plans are generated to use the resources of Georgia’s Amazing Coast and the COASTeam Aquatic Curriculum. Lessons are aligned to the SOUTH CAROLINA SCIENCE CURRICULUM STANDARDS and are written in the “Learning Focused” format. South Carolina Our Amazing Coast Table of Contents Grade 3 Curriculum…………………………………………………………….................1 – 27 Grade 4 Curriculum……………………………………………………………………...28 – 64 Grade 5 Curriculum……………………………………………………………………...65 – 91 SC Background………………...…………………………………………….…………92 – 111 Fast Facts of SC………………...……………………………………………………..112 – 122 Web Resources………………...……………………….……………………………...123 - 124 South Carolina: Our Amazing Coast Grade 3 Big Idea – Habitats & Adaptations 3rd Grade Enduring understanding: Students will understand that there is a relationship between habitats and the organisms within those habitats in South Carolina. South Carolina Science Academic Standards Scientific Inquiry 3-1.1 Classify objects by two of their properties (attributes). 3-1.4 Predict the outcome of a simple investigation and compare the result with the prediction. Life Science: Habitats and Adaptations 3-2.3 Recall the characteristics of an organism’s habitat that allow the organism to survive there. 3-2.4 Explain how changes in the habitats of plants and animals affect their survival. Earth Science: Earth’s Materials and Changes 3-3.5 Illustrate Earth’s saltwater and freshwater features (including oceans, seas, rivers, lakes, ponds, streams, and glaciers). -

Grades Prek–K Through 5

UNEDITED DRAFT Grades PreK–K through 5 GENERAL MUSIC CURRICULUM GUIDE UNEDITED DRAFT GENERAL MUSIC K-5 Grade Span: PreK-K I. Singing: Students will sing, alone and with others, a varied repertoire of music. South Carolina Standard Activities/Topics/Resources Assessment Strategies A. sing songs in a Teacher observation developmentally appropriate Additional South Carolina Standards range (using head tones), H. Demonstrate voice types by calling, whispering, speaking, singing, and by using vocal expressions to Teacher checklist matching pitch, echoing short, show emotion: crying, laughing, rejoicing, cheering, etc. PreK-K VI D Example: melodic patterns and I. Sing a variety of songs including play, story, game, folk, cumulative, and seasonal songs PreK-K IX - working to accomplish objective maintaining a steady tempo. A,B . √ accomplished objective B. speak, chant, and sing, using + exceeded objective expressive voices, moving to Rubric demonstrate awareness of beat, Examples of kindergarten age–appropriate songs: tempo, dynamics, and melodic Mary Had a Little Lamb The Farmer In the Dell Student portfolio direction. Ring Around the Rosy Happy Birthday C. sing from memory age- Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star The Alphabet Song Performance appropriate songs representing Old McDonald Had a Farm If You’re Happy varied styles of music. The Muffin Man Ambos A Dos “Assessing the Developing Child D. experiment with high, This Old Man Eensy, Weensy Spider Musician: A Guide for General middle, and low vocal pitches by Vocabulary: Music Teachers, Brophy imitating known sounds such as high singing sirens, shrieks, and animals. middle head voice PreK-K VI C, low pitch E. experiment with and locate upward calling head tones through activities downward whispering such as pretending to throw repeat speaking voice upward, baby talking in head voice, and reciting nursery rhymes in head voice. -

Detective Bonz and the Sc History Mystery

Teacher’s Guide DETECTIVE BONZ AND THE SC HISTORY MYSTERY An instructional television series produced by Instructional Television, South Carolina Department of Education and South Carolina ETV (Equal Opportunity Employers) User guide written by: Margaret Walden, Richland School District Two Kathy Bradley, Brennen Elementary School User guide developed/edited by: Dianne Gregory and Rhonda Raven, ITV Series production by: Linda DuRant and Bette Jamison, Executive Producers Pat Henry, Director/Co-Producer/Editor Kathy Bradley, Writer/Co-Producer Rhonda Raven, Production Assistance The South Carolina Department of Education does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, or handicap in admission to, treatment in, or employment in its programs and activities. Inquiries regarding the nondiscrimination policies should be made to: Personnel Director, 1429 Senate Street, Columbia, SC 29201, 803-734-8505 TABLE OF CONTENTS HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE ............................................................................1 CHAPTER ONE...............................................................................................3 (Spends most of the time setting up the story that unfolds in the remaining chapters and then talks about ancient South Carolina.) CHAPTER TWO ..............................................................................................9 (Focuses on the early settlers, Spanish explorers, Lords Proprietors, Charleston, and pirates.) CHAPTER THREE ........................................................................................21 -

Mr. John Henry Gantt

The Friend, Daughters, Sons, Sisters, Brothers and Grandchildren Pallbearers invite you to share in Family & Friends Home-Going Services Floral Bearers for Family & Friends Mr. John Henry Gantt Sunrise: Sunset: In Tribute November 16, 1939 February 23, 2018 God saw he was getting tired And a cure was not to be, So He put His arms around him And whispered, “Come with Me.” With tearful eyes we watched him suffer And saw him fade away, Although we loved him dearly, We could not make him stay. A golden heart stopped beating, Hard working hands to rest, God broke our hearts to prove to us He only takes the best. Arrangements Entrusted To R. O. LEVY HOME FOR FUNERALS Reuben O. Levy – Mortician Dr. John Summers – Funeral Director 415 Cedar Street Batesburg-Leesville, South Carolina 29070 (803) 532-4088 Fax (803) 604-8713 www.rolevy,com [email protected] Thursday, March 1, 2018 • 2:00 p.m. FULL SERVICE HOME FOR FUNERALS PROFESSIONAL EMBALMING SHIPMENT SERVICE R.O. Levy Home for Funerals Chapel LICENSED IN SOUTH CAROLINA NEW YORK 415 Cedar Street Service With Understanding And Care Batesburg-Leesville, South Carolina Printing and Graphics by Betty Graphix 803-414-0972 Reverend Inez Cook, Presiding Reflections of Life Order of Service Reverend Inez Cook, Presiding MR. JOHN HENRY GANTT, 78, son of the late Paul and Willing Workers for Musical Selections Lessie “Babe” Gilree Gantt, was born November 16, 1939 in Saluda County, South Carolina. He departed this earthly life PROCESSIONAL on Friday, February 23, 2018. Clergy & Family Mr. Gantt was educated in the public schools of Saluda OPENING HYMN County, attending Hollywood School. -

Sandhills/Midlands Region

SECTION 4 SANDHILLS / MIDLANDS REGION Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 4 SANDHILLS / MIDLANDS REGION - Index Map to Sandhills / Midlands Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 4 - Power Thinking Activity - "Traffic Troubles" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 4-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Sandhills / Midlands p. 4-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 4-3 . - Fall Line Zone p. 4-3 . - figure 4-1 - "Map of Fall Line Zone" p. 4-4 . - Sandhills Soils - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 4-5 . - Landforms Influenced the Development of Cities p. 4-5 . - Choosing a Site for the New Capital p. 4-6 . - Laying Out the City of Columbia p. 4-7 . - The Columbia Canal and Water Transportation p. 4-7 . - story - "The Cotton Boat" p. 4-8 . - The Secession Convention and the Onset of the Civil War p. 4-8 . - Columbia's Importance to the Confederacy p. 4-8 . - Sherman's March Through South Carolina p. -

Breaking Ground

05/01 UDT Pgs 1,3 4/30/10 3:45 PM Page 1 May 1, 2010 RELIVE HISTORY Saturday50¢ Saturday from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. and again Sunday 10 a.m.-4 p.m. at the Cross Keys House as it travels back in time for the Living History Event III which will feature a reenactment of a luncheon with Jefferson Davis and several other activities! 100% recycled newsprint The Union Daily Times To subscribe, call 427-1234 Your hometown newspaper in Union, South Carolina, since 1850 Vol. 160, No. 86 www.uniondailytimes.com BREAKING GROUND FOR THE FUTURE Town of Lockhart turns out for ceremonies celebrating new Dollar General store By NATHAN CHRISTOPHEL [email protected] LOCKHART — Friends, colleagues, dignitaries and com- munity members gathered across the intersection of SC Highway 9 and Woodside Drive just outside Lockhart town limits to celebrate the beginning of a new chapter for the eastern Union County community. “We are so proud to be here,” said Lockhart Mayor Ailene Ashe. “I appreciate everybody here.” She and the more than 50 people in attendance welcomed Dollar General into the Lockhart business community with Nathan Christophel photos/Times a groundbreaking ceremony Friday morning at the site Above, Union County Supervisor Tommy Sinclair, Lockhart council members Lee Brannon and Glen Stein, Lockhart Mayor Ailene where the discount retailer is building its newest Union Ashe, Lockhart council member Tammy Stamey, Dollar General Corporation Real Estate Manager for South Carolina and Western County store. “Dollar General is very excited and looks forward to get- North Carolina Tom Brown and owner of Patton Construction Tab Patton break ground at the site where Lockhart’s new Dollar General store will be located. -

PROGRAM at University of South Carolina

Sustainable Public History ANNUAL MEETING OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON PUBLIC HISTORY 19-22 March 2014 Monterey Conference Center Monterey, CA PUBLIC HISTORY PROGRAM at University of South Carolina EXPLORE½¶ÇÁºÈÉÄöùüÁ¶Ã¹É½ÇÄʼ½ÄÃȾɺIJºÁ¹È¸½ÄÄÁÈÄÁÁ¶·ÄǶɺ̾ɽ ɽº¨Â¾É½ÈÄþ¶ÃÄÃɽºÍ½¾·¾É¾Ã¼¡Ä¸¶ÁÃɺÇÅǾȺ¾Ã¾É¾¶É¾Ëº¥ÇºÈºÇ˺ɽº¨ÄÊɽĩÈ »Ç¾¸¶ÃºǾ¸¶Ã½ºÇ¾É¶¼ºÃ¼¶¼º¶Ã¹¾ÃɺÇÅǺÉɽºÅÇÄ·ÁºÂ¶É¾¸¶ÁŶÈɹËĸ¶Éº »ÄÇÂÊȺÊÂÈÄöžÉÄÁ¾ÁÁ¨ÉʹÎÅÊ·Á¾¸½¾ÈÉÄÇζÉɽºªÃ¾ËºÇȾÉÎÄ»¨ÄÊɽ¶ÇÄÁ¾Ã¶ please visit us at artsandsciences.sc.edu/hist/pubhist/ ANNUAL MEETING OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON PUBLIC HISTORY 19 - 22 March 2014 Monterey Conference Center Monterey, CA Tweet using #ncph2014 1949 Centennial, Courtesy of Monterey Public Library, California History Room CONTENTS Schedule at a Glance .......................4 Registration .....................................6 Hotel Information .............................6 Travel Information ...........................7 History of Monterey ..........................8 Places to Eat ..................................11 Things to Do ...................................12 Field Trips ......................................14 Special Events ................................17 Workshops .....................................19 Conference Program .....................23 Index of Presenters ........................38 NCPH Committees .........................40 Registration Form ..........................63 2014 PROGRAM COMMITTEE MEMBERS Briann Greenfield, New Jersey Council for the Humanities (Co-Chair) Leah Glaser, Central Connecticut State -

Digital Collections

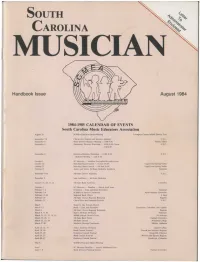

SOUTH CAROLINA MUSICIAN Handbook Issue August 1984 1984-1985 CALENDAR OF EVENTS South Carolina Music Educators Association August 25 SCMEA Executive Board Meeting Lexington County School District Two September 7-8 Choral Arts Seminar and Business Meeting U.S.C. September 8 Band Division Business Meeting — 2:00 P.M. Spring Valley September 8 Elementary Division Workshop — 10:00 A.M.- U.S.C. 1:30-2:30 September 8 Orchestra Division Workshop — 10:00 A.M. Business Meeting — 2:00 P.M. October 1 SC Musician — Deadline November-December Issue October 20 Marching Band Festival — A and AAAA Lugoff and Spring Valley October 27 Marching Band Festival — AA and AAA Lugoff and Spring Valley October 27 Junior and Senior All-State Orchestra Auditions Regional November 9-10 All-State Chorus Auditions U.S.C. December 8 Solo Auditions — All-State Orchestra January 23, 24, 25, 26 All-State Band Auditions February 1 SC Musician — Deadline — March-April Issue February 1-2 Orchestra — Solo and Small Ensembles Regional February 7-9 SCMEA In-Service Conference Hyatt Regency Greenville February 15-16 Regional Band Clinics 4 Sites February 16 All-State Chorus Regional Rehearsal Regions February 23 Choral Solo and Ensemble Festival U.S.C. March Music In Our Schools Month March 1-2 Band — Solo and Ensemble Charleston, Columbia, and Upstate March 2 All-State Chorus Regional Rehearsals Regions March 8, 9, 10 Senior All-State Orchestra Anderson March 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Middle School Choral Clinics 9 Locations March 15, 16, 17 All-State Band Clinic Furman University